Drinkwater J.F. The Alamanni and Rome 213-496 (Caracalla to Clovis)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

As Kreuz says, we must be careful in how we judge this. What we have is

not so much a ‘primitive’ as a diVerent sort of society, in which the

preservation of social traditions was more important than possible

gains through economic risk. The experimentation with wheel-

thrown ceramics, and even the heavier draught animals, may have

been the work of a reforming elite group or groups that enjoyed only

short-lived predominance.140

It is odd that the more distant Main-Germani appear to have

had more to do with the Empire than the Lahn-Germani. Similar

unpredictability has been noted in Thuringia, in a study of the settle-

ment at Su

¨

lzdorf. Roman artefacts have been found throughout

Thuringia, and faunal studies suggest Roman inXuence on animal

breeding, in particular of cattle, horse and dog.141 In Su

¨

lzdorf, however,

artefacts and inXuence are lacking. To explain this, the excavator pro-

poses local conservatism.142 Inasense,therefore,Su

¨

lzdorf ma y be seen

as the non-Romanizing exception that proves the Romanizing rule.

Again, however, the long-term impact of Roman inXuence on the

quality of animal stock generally in Thuringia has been questioned.143

What conclusions may be drawn from this review of Germanic

archaeology? First, as in the case of the Alamanni, there is no clear

correlation between the historical and archaeological evidence. For

example, without the literary sources we would have no inkling of the

existence of the Chatti. Secondly, however, we can see the power that

Rome had to disrupt Germanic society, already visible in the histor-

ical sources. Across Franconia there appears to have been a major

break in settlement, from the Wrst into the second century ad. This

has also been observed recently along the High Rhine, between Basel

and Lake Constance.144 Only when Rome settled down could the

Empire’s Germanic neighbours Wnd some peace. But, thirdly, there is

now no doubt that Germani were attracted to Roman military sites.

This occurs very early, at the time of the Augustan campaigns, and

may also account for the settlements in the Lahn valley and on the

middle Main. The phenomenon of barbarians ‘setting up house on

140 Cf. Kreuz (2000: esp. 238–9).

141 Teichner (2000: 86–7).

142 Teichner (2000: 87–8).

143 Benecke (2000: 253); cf. Teichner (2000: 87, n.42).

144 Trumm (2002: 212).

38 Prelude

the doorstep of their supposed enemy’ has also been noticed on the

Danube.145 It is reminiscent of Alamannic behaviour in the late third

and fourth centuries; and, as in the case of the Alamannic settle-

ments, we must suppose that the Rhine–Weser communities existed

only under Roman licence and, perhaps, even encouragement.146

This notion of Xuctuation in population is not without its diYcul-

ties. At the likely site of the clades Variana, at Kalkriese, the presence of

Germanic warriors can be deduced only from Roman military

remains. Similarly, without the help of Roman imports, it is very

diYcult to identify and date Germanic settlements, therefore the

absence of imperial goods may create a false impression of demo-

graphic voids. It has been remarked, for example, that relatively high

levels of Germanic pottery in the Augustan fort at Waldgirmes suggest

a signiWcant population in the Lahn valley, which would accord w ith

the occurrence of native coinage in the area; but we do not know the

sites at which these pots were produced. Likewise, pollen data in the

Lahn valley and the Wetterau have been interpreted as indicating that

both areas continued to be worked at more or less the same level of

intensity from the Celtic through to the Germanic and Roman

periods, suggesting no marked variations in population. Archaeolo-

gists may in the end detect technical Xaws in the palynology or

discover a highly peripatetic form of local agriculture which allowed

a small population to spread cultivated pollens over a wide area, but

for the moment there is certainly a discrepancy between the historical

and archaeological, and the palynological evidence.147

It is, therefore, undeniable that, in Whittaker’s phrase, the area

around the Upper German/Raetian limes became a ‘zone of inter-

action’ as Germani were drawn to the frontier and appreciated the

material beneWts of imperial life. One is tempted, like Whittaker, to

cite Cassius Dio’s description of the natives’ adaptation to the Roman

world in the Augustan province of Germania prior to Varus: ‘they

were becoming diVerent without realizing it’.148 On the other hand, it

145 Burns (2003: 231).

146 Below 82, 89. A. Wigg (1997: 63), (1999: 49).

147 Stobbe (2000: 217); Abegg-Wigg et al. (2000: 56); Lindenthal and Rupp (2000:

74); Schnur bein (2003: 103–4). There is no sign of the general surge in the

‘Germanic-dominated’ population of Europe proposed by Heather (2005: 86–7).

148 Dio 56.18.3. Whittaker (1994: 130).

Prelude 39

is important not to exaggerate the scale of the phenomenon. Dio’s

Germani were in the throes of full provincialization, stimulated by

the facilities prepared for them at sites such as Waldgirmes.149 With

this abandoned, the process of acculturation became uneven and

unspectacular. Above all, it appears to have produced no signiWcant

polarization of political and military power, reXected in, say, the

concentration of high levels of impor ted artefacts at par ticular sites.

In other words, against Whittaker, in this region at least we can see no

rise of a sophisticated barbarian elite, willing to pursue its interests in

the Empire peaceably or, if necessar y, by force.150

Certainly, whatever was to follow in the later Empire, there is no

sign here of the emergence of a new and dynamic composite culture, a

‘Mischzivilisation’, spanning the nominal frontier line and absorbing

barbarians and Romans alike.151 Recent research has emphasized the

lack of cultural movement in the opposite direction, that is the lack of

impact of Germanic ways on imperial border life, and this despite the

fact that, along with Gauls, Rome appears to have settled some

Germani in the Agri Decumates.152 Althoug h they have their prob-

lems, name-studies have failed to reveal any signiWcant number of

Rhine–Weser Germani in Heddernheim.153 Likewise, Bo

¨

hme-

Scho

¨

nberger has noted the absence of Germanic inXuence on

Roman dress in the western border areas under the Early Empire.154

Where we can glimpse acculturation in action, Germani go imperial.

It was not until the Wfth century that provincial Romans went

Germanic, following the Frankish domination of Gaul. Until then,

the stronger culture predominated.155 The exception might seem to

149 Schnurbein (2003: 104); above 20.

150 Whittaker (1994: 127, 215–22); cf. Burns (2003: 231–2).

151 On ‘Mischzivilisation’, see further below 348–57. Elsewhere from the Wrst to the

third centuries, in the northern Netherlands, Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein,

the Empire seems to have exercised a surprising ability to control the Xow of its

manufactured products to Germani, strictly according to its own military and

political needs: Erdrich (2000a: 195–6), (2000b: 228–9), (2001: 79–135, 139–43,

146–50 (English summary)). The inhibition of a free market in such goods can

only have hampered material acculturation.

152 The ‘Neckar Suebi’: Heiligmann (1997: 58).

153 Scholz (1997).

154 Bo

¨

hme-Scho

¨

nberger (1997).

155 Bo

¨

hme-Scho

¨

nberger (1997: 9–10), cf. Halsall (2000: 180): ‘So, at least until

about 400, if the cultural frontier zone was deepening, it was spreading from

northern Gaul into Germania Libera and not vice versa.’

40 Prelude

be military equipment: the Roman army always adopted the best

weapons of its opponents. Even here, however, one of the best

known cases of Roman borrowing, that of the spatha, is less straight-

forward than it seems, since the long-sword appears to have

mixed—Germanic, but also Celtic and eastern—origins.156

Overall, therefore, there is no clear archaeological evidence for a

high degree of direct Germanic pressure on the upper Rhine and

upper Danube frontier from the Wrst to the early third centuries ad.

As far as can be seen, there were few Germanic settlements directly on

the limes, and not many in its vicinity. Even if this is unreliable, and

there were many more Germani in the area, we have to conclude from

the absence of Roman artefacts that most of them can have had little

contact with the Empire or its products. As the excavators say of the

Lahn Germani, though neighbours, they were ‘distant neighbours’.157

Without direct pressure on the Empire, where was danger likely to

come from? There mig ht, as in the case of the Marcomannic Wars,

have been short-term diYculties with immediately adjacent, nomin-

ally friendly communities. In the longer term, the most likely threat

was long-distance raiding—chronic but relatively infrequent and

certainly manageable until it ran out of control in the third cen-

tury.158 If, as has been suggested from Wnds of brooches,159 distant

Germani could, from the Wrst century, travel west to the Upper

German/Raetian frontier to Wnd service in the Roman army, they

could do the same in war-bands. But the limes system was well able to

cope with this level of aggression.160

If there was no pressing Germanic threat, why did early Roman

emperors make so much of the Rhine frontier? Here, we return to the

political symbiosis which is the main theme of this chapter. Funda-

mentally, the Germanic threat on the Rhine was played up by Roman

emperors because it suited them to do so. Imperial campaigns

occurred because the princes involved found them useful in acquiring

or enhancing a military reputation (Tiberius, Domitian), steadying

156 Gechter (1997: esp. 14); cf. below 341–2.

157 Abegg-Wigg et al. (2000: 63): ‘entfernte Nachbarn’.

158 Witschel (1999: 205); cf. below 49.

159 Bo

¨

hme-Scho

¨

nberger (1997: 9).

160 Cf. Creighton and Wilson (1999: 25): the proximity of numerous villas to the

limes in, say, Taunus or Raetia, as a sign of ‘just how peaceful conditions must have

been on the frontier for decades’.

Prelude 41

their armies in uncertain political or military situations (Germani-

cus), and providing them with a reason to go to or remain in the west

when, for political reasons, it suited them to be there (Gaius). Fur-

thermore, imperial exploitation of neighbouring barbarians was

essential in justifying the very position of the princeps, as Republican

warlord became legitimate emperor. Emperors needed to foster the

support of the army because, in the last resort, their power depended

on its obedience. One of the best ways of obtaining such support was

to lead their troops successfully against foreign foes, winning them

and themselves honour, glory and booty and, as far as the wider

political nation was concerned, reinforcing Roman beliefs in Rome’s

divinely ordained mission of world domination.161 Germania was an

abundant source of such foes. In addition, since the institution of a

large standing army was relatively new in the Empire, expensive and,

as emperors began to Wnd to their cost, potentially dangerous as a

breeding ground for disaVection, the army and its maintenance had to

be justiWed and its potential political threat reduced. All this could be

achieved by laying stress on outlying enemies, against whom the

troops were projected as the Empire’s sole defence, and to counter

whom units could be distributed along the frontier, supported by

local populations and at a safe (or, at least, safer) distance from the

imperial centre and from each other. Tacitus hinted at this deceit

when he claimed that the task of the Rhine army was as much to watch

Gauls as Germani, but this was not even half the story. The vast

majority of Gauls were, very soon, loyal Roman subjects and tax-

payers; and, as Syme says, ‘no enemy was likely to come from the

Black Forest’.162 There was no real threat either way: from the start

Roman forces were stationed on the frontier not to counter a major

‘barbarian menace’, external or internal, but out of imperial political

needs.163

161 e.g. Burns (2003: 10–12, 93, 209, 272–4, 283); Isaac (1992: 379–83).

162 Tacitus, Annales 4.5.1: commune in Germanos Gallosque subsidium. Syme

(1999: 87).

163 Below 360–1; cf. Guzma

´

n Armario (2002: 122). Burns (2003: 18–19, 30, 141,

152–3, 175–6).

42 Prelude

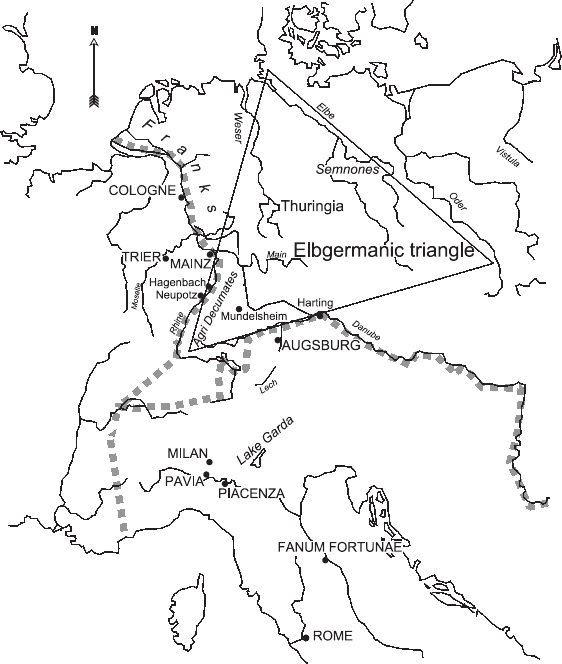

2

Arrival

Tacitus described a great arc of tribes, from modern Wu

¨

rttemberg to

the Vistula, which he classiWed as ‘Suebi’. The ‘oldest and noblest’ of

these were the Semnones, whom Tacitus appears to have located on

the middle Elbe.1 It used to be thought that the Alamanni were an

old Suebian tribe under a new name, or a new but distinctly

Suebian tribal confederation that, from around 200, pressed ever

harder against the Rhine/Danube limes and then, at a speciWc date

(traditionally 259/60), broke through and settled in part of Upper

Germany and Raetia.2 The Wrst sign of this pressure was taken to be

Caracalla’s Germanic campaign of 213, which took him over the

frontier from Raetia and into conXict with Werce people described

in Cassius Dio’s contemporary ‘Roman History’ as Albannoi,

Alambannoi,orKennoi. Dio’s account is apparently conWrmed by

Aurelius Victor who, writing in the middle years of the fourth

century, explicitly describes Caracalla’s victories over Alamanni

near the river Main.3 However, simple invasion was questioned by

Wenskus as part of his discussion of ethnogenesis, and the current

communis opinio is that there was no third-century Suebian ‘Vo

¨

lk-

erwanderung’—no ‘migration’—and no sudden and decisive ‘Land-

nahme’—no ‘occupation’. Rather, it is now generally believed, the

Alamanni came into being only after various Germanic groups found

1 Tacitus, Germania 38–45, esp. 39.1.

2 For a summary of such thinking, see Geuenich (1997a: 11–15, 22); Pohl

(2000: 29).

3 Dio 77(78).13.4–6, 14.1–2, 15.2 [Loeb]; CIL 6.2086 (ILS 451); Quellen 1, 9–11;

Aurelius Victor, Caesares 21.2: Alamannos . . . prope Moenum amnem devicit. Cf. below

141–2.

themselves living permanently on former imperial territory.4 Here

occurred what might be termed ‘ethnogenesis sur place’ as the new-

comers interacted with each other, and with Rome.5

An important element in the evolution of this hypothesis was that

Greco-Roman usage of ‘Alamanni’ and ‘Alamannia’ did not begin

until the late third century, being marked by the appearance of

‘Alamanni’ in a Latin panegyric of 289.6 On this view, references to

Caracalla’s Alamanni in Cassius Dio are later interpolations or

glosses; and Aurelius Victor projected the present upon the past.7

This interpretation has recently been challenged by Bleckmann, who

demonstrates the special pleading needed to sustain it and shows that

there is no reason to doubt that Caracalla fought people whom he

knew as Alamanni beyond the Danube in 213.8 I would add that by

289 the word ‘Alamanni’ must have been suYciently long in circula-

tion for the cultivated Gallic orator who delivered the panegyric to

Maximian to deploy it without fear of being accused of neologism.

(After all, he goes out of his way to avoid the term ‘Bagaudae’.9)

The reinstatement of the earlier occurrence of Alamanni is

important for the history of the name.10 It is, however, less signiWcant

for the understanding of what happened in the third centur y. It

does not compel a return to ‘migration’ and ‘occupation’. Acceptance

of the ‘289 argument’ allowed historians to see the evidence in a

4 Wenskus (1961), 499–500, 506–7, citing Bauer and Dannenbauer. The notion of

their ethnogenesis in Alamannia was propounded independently by Springer,

Castritius and Okamura: cf. Castritius (1998: 353 and n. 14, referring also to Kerler).

I Wrst encountered it in Okamura’s meticulous doctoral dissertation (1984). The

implications of his ideas were pursued by Nuber (1990), (1993), (1997). See also,

more recently, Keller (1993: 83–6, 89–91); Geuenich (1997a: 11–12, 17), (1997b: 73,

76–7); Schach-Do

¨

rges (1997: 98); Nuber (1998: 378–9); Steuer (1998: 280–1).

5 Keller (1993: 91, 96–7); Nuber (1993: 103); Geuenich (1997a: 16–17), (1997b:

74, 76); Martin (1997a: 119); Schach-Do

¨

rges (1997: 79, 85); Steuer (1997a: 149);

(1998: 275–6, 278, 281, 315, 317); Castritius (1998: 357); Wolfram (1998: 613). A

modern version of the traditional view has, however, been proposed by Strobel (1996:

131–5), (1998: 86–7), (1999: 16–21); cf. below nn. 94, 101.

6 Pan. Lat. 2(10) [Galletier].5.1; cf. below 180.

7 Okamura (1984: e.g. 86, 90–1, 116–17); Keller (1993: 90); Nuber (1993: 102 and

n.27); Geuenich (1997a: 18–19). Cf. Castritius (1998: 353 and n.14); Steuer (1998:

274–5); Pohl (2000: 103).

8 Bleckmann (2002).

9 Drinkwater (1989: 193).

10 Below 63.

44 Arrival

diVerent light. Whatever the original meaning of the term ‘Alamanni’

and the manner in which it became attached to a certain set of

people, the lesson of fourth-century history and archaeology is that

there was no invasion by a single, fully Xedged people or consciously

related association of tribes.11 Roman writers clearly had very little

idea as to who the Alamanni were and where they came from and nor,

apparently, had the Alamanni themselves. Unlike Goths, Lombards

and Franks, they do not appear to have possessed ancient stories

tracing their ancestry back to a mythical past.12 The absence of any

royal or aristocratic ‘Traditionskern’—‘core of tradition’—distances

Alamannic studies from current debate concerning the validity of the

concept of ethnogenesis which is concerned most of all with whether

each of these other peoples possessed its own such ‘core’.13 An

attempt has been made to locate an ancient religious tradition at

the heart of Alamannic identity, but it relies too much on cultural

continuity in rapidly changing circumstances.14 Alamannic ethno-

genesis sur place can now stand on its own feet. South-west Germany

was taken over gradually by a number of small and scattered groups

which slowly became ‘the Alamanni’. During the third century,

‘Alamanni’ was a description of ty pe, not nationality: a generic, not

an ethnic.15

This makes the identiWcation of the Alamannic place of origin

much less of an issue than used to be the case in Germanic

scholarship.16 However, scholars seem to agree that the models of

Alamannic jewellery and ceramics and burial places originated in

the lands on and to the east of the Elbe, from Mecklenburg to

Bohemia. These types of artefacts and structures, termed ‘Elbger-

manic’, spread into an area which may be roughly described as an

inverted triangle, with its base on the Elbe and its apex in the

11 Thus contra Bleckmann (2002: 146, 150, 168 (‘Grossstamm’, ‘Volk’, ‘Gruppe/

Stamm mit eigener Identita

¨

t’)). Below 86, 124–6.

12 Steuer (1998: 276–7).

13 e.g. Amory (1997: 36–8). More recently Bowlus (2002: 245–6); Fewster (2002:

140); GoVart (2002: 21–3, 30–7); Kulikowski (2002: 72–4); Murray (2002: 46, 64–5);

Pohl (2002b: 222, and see 228–32 for a summary and defence of the ‘more di Vuse’,

post-Wenskus, conception of the ‘Traditionskern’).

14 Below 125.

15 Cf. below 62 and, esp., 67.

16 Cf. Steuer (1997a: 150), (1998: 278, 283, 287, 317).

Arrival 45

Rhine–Danube re-entrant17 (Fig. 5). Assuming that such an expan-

sion in some way reXects movement of people, 18 it has to be conceded

that the new approach locates the ancestors of the Alamanni Wrmly in

the western section of Tacitus’ ‘Suebia’. Thus, as some critics have

waspishly observed of ethnogenesis as a whole, the new version does

not appear signiWcantly diVerent from the old.19 However, it does not

presuppose massive tribal migration or even a uniform ethnic or

political background for the people concerned. Further, it allows for

cultural, economic and political inXuences to circulate west to east, as

well as east to west, within the triangle.20

Some awareness of the arrival of people from Suebia may explain

why, in the works of some late-fourth/early-Wfth-centur y poets,

Germani who in the terms of this study are clearly Alamanni are

occasionally termed ‘Suebi’.21 It is unlikely that the writers concerned

possessed a deep understanding of contemporary developments

within the Elbgermanic triangle. Much more probable is that they

repeated the traditional ethnography of their education, that is the

Tacitean model, ‘conWrmed’ by later experience.22 This also gave

them a word—disyllabic Suebi—better suited to the complexities of

Latin metre than trisyllabic Alamanni.23 But ‘Suebi’ was a very

imprecise term. For practical reasons Romans needed to come to

grips with Elbe-Germani in or by the Rhine–Danube re-entrant. They

needed to categorize the area and the people it contained, and for this

purpose fell upon ‘Alamannia’ and ‘Alamanni’.24 The emphasis must

17 Fingerlin (1993: 60); Nuber (1993: 103); Martin (1997a: 119); Schach-Do

¨

rges

(1997: 79, 81–95); Steuer (1997a: 149, 151–2, 154), (1998: 291–301 and Fig. 2, 314,

316); Bu

¨

cker (1999: 216); Haberstroh (2000b: 227).

18 As Steuer (1998: 301).

19 Tacitus, Germania 38–45; cf. Pohl (2000: 21–2). GoVart (2002: 31).

20 As I understand it, this is the main force of Steuer’s insistence (e.g. (1998: 295,

297, 306, 311) on ‘Verkehrsra

¨

umen’ and ‘Verkehrszonen’—the spontaneous emer-

gence of a number of areas of production and circulation (of artefacts, customs and

fashions), linked by established regional lines of communication (‘Verkehrsbahnen’)).

See also Brather (2002: 161–2).

21 Ausonius 13.3.7, 4.3; 17.1.2; 20.2.29 [Green]; Claudian, In Eutrop. 1.394; De

Cons. Stil. 1.190.

22 Below 60.

23 Green (1991: 535); Heinen (1995: 82). Bleckmann (2002: 157 n. 46).

24 Lorenz, S. (1997: 18) and, esp., below 68–9.

46 Arrival

Po

Rhône

Rhône

Meuse

Limes

CENTRAL EMPIRECENTRAL EMPIRE

DALMATIA

PANNONIA

NORICUM

RaetiaRAETIA

GALLIC EMPIRE

GALLIC EMPIRE

GALLIC EMPIRE

Saône

Fig. 5 The north-western provinces, third century.

Arrival 47