Drinkwater J.F. The Alamanni and Rome 213-496 (Caracalla to Clovis)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

reduction in the Rhine garrison. Over 30 years, the number of legions

stationed there was cut from six to four.96

Peace, or lack of major activity, persisted under Trajan (98–117),

Hadrian (117–38) and Antoninus Pius (138–61). It ended under

Marcus Aurelius (161–80). Again, we hear of border warfare on the

Rhine and upper Danube with, in 161 and 162, raiding by Chatti and,

in 170–5, by Chatti and Chauci.97 However, the greatest conXicts of

the period were the Marcomannic Wars. This is the name given to the

wars fought by the emperor Marcus Aurelius along the Danubian

frontier in the period 168–80. The reconstruction of the sequence of

these events and their precise chronology is contentious.98 In what

follows, I rely on A. R. Birley.99

On succeeding Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius took as his co-

emperor his step-brother, Lucius Verus. Almost immediately there

was trouble in the east, and Lucius led a successful Parthian war from

162–6. Even before this war was over, Marcus was preparing a new

campaign on the Danube. This began in 168, but was interrupted by

the death of Lucius early in 169. It recommenced in 170, when a major

Roman operation provoked barbarian incursions deep into the

Empire: Quadi and Marcomanni reached northern Italy and Costoboci

attacked Eleusis. Marcus and his generals acted swiftly to drive out the

invaders, and then attacked them on their home territory. From 171–

5 there was Wghting against Marcomanni, Quadi and, further east,

Iazyges, in which the Romans did well. However, this had to be given

up on news of rebellion in the east, led by Avidius Cassius. After

Cassius’ defeat, Marcus returned to the Danube in 178, accompanied

by his son and heir, Commodus. He repeated his earlier success. The

period 179–80 saw the defeat of the Quadi, the submission of the

Iazyges and the wearing down of the Marcomanni. Final victory

seemed in sight; but early in 180 Marcus fell ill and died. Commodus

made peace with the barbarians and ended the Wghting.

The traditional interpretation of the Marcomannic Wars is heavily

inXuenced by our sources’ positive assessment of Marcus Aurelius,

96 Drinkwater (1983a: 60, 62).

97 Historia Augusta, V. Marci 8.7–8; V. Didii Iuliani 1.6–8. Drinkwater (1983a: 76).

98 Garzetti (1974: 484).

99 Birley (1987: 140–210, 249–55).

28 Prelude

and by our knowledge of what was to happen to the Roman Empire

from the third century. In short, Marcus is seen as the Wrst Roman

emperor to face the rising tide of Germanic migration, and the one

who strengthened imperial defences just enough to hold it back for

another couple of generations.100 Much stress is laid on the attack on

Italy of 170: the Wrst by foreigners since the Cimbri in 102 bc, and a

harbinger of the Iuthungian and Alamannic attacks of 260,101 and of

Alaric’s sack of Rome, the very embodiment of the ‘Germanic threat’,

in 410.102 However, it is possible to paint a diVerent picture. A

principled man set on doing his public duty can be just as dangerous

to ordinary people as a self-seeking rogue.

Marcus came to power relatively old (he was born in 121), and with

no militar y experience. Indeed, as Birley observes, it is likely that until

168 he had never left Italy.103 He delegated the eastern war to the

younger Lucius, and Lucius did well. Had he been an ordinary

Roman em per or, Marcus would have felt obliged to emulate his col-

league’s success; but Marcus was more than that. Apart from his own

personal standing, he will have been conscious of the demands of duty:

to undertake himself what he asked of subordinates; and, above all, to

do right by the Empire over which he ruled.104 There is also his state of

mind. His private me morandum book, now kno wn as his ‘Medit a-

tions’, shows that he was now absorbed with issues of mortality, and by

the conviction that his own death was at hand.105 Such reXections are

likely to have been stimulated by chronic illness and more recent

incidents such as the arrival of the plague and the deaths of Lucius

and his own young son in 169. In such a state, he may have seen war not

just as a means of demonstrating his abilities as leader but also as a test,

an act of self-sacriWce, through which he might expiate whatever it was

that was causing Heaven to inXict such suVering on his Empire. This

would explain the attention that was given, once hostilities had begun,

to various ‘miracles’ which showed the return of divine favour.106 It is

100 Garzetti (1974: 506).

101 Below 52, 70–2.

102 Cf. Birley (1987: 249).

103 Birley (1987: 156).

104 Cf. Birley (1987: 214, 216); Lendon (1997: 115–16).

105 Cf. Birley (1987: 185, 214, 218–20).

106 Cf. Garzetti (1974: 493); Birley (1987: 252–3).

Prelude 29

no surprise, therefore, that Marcus was preparing a Germanic war even

before the end of th e Parthian war. There is no ne ed to suppose that th is

war was a response to a major new threat. Germanic raiding was a

feature of frontier life.107 It could never have been diYcult for any

Roman ruler looking for a war to Wnd a justiWcation for action in one of

these incursions. But in 170 things went badly wrong, and instead of

Romans attacking barbarians, barbarians attacked the Empire.108

The basic cause of this trouble has usually been sought in the

beginnings of the ‘Vo

¨

lkerwanderungszeit’: the ‘Period of Migration’.

As Goths moved from Jutland to the Black Sea, they pressured

peoples to their south and west, who in turn pressured peoples on

the borders of the Roman Empire, taking them, as Birley puts it, to

‘breaking point’ and forcing them to cross the imperial border.109

Local factors have also been taken into account in explaining the Wnal

push of Marcomanni, Quadi, etc. into the Empire, such as rising

population, caused by the more sedentary life created by their being

held at the imperial frontier.110 However, the domino eVect remains

the major explanation: for a spell, the Empire was swamped by the

rising Germanic tide. However, what happened was short-term raid-

ing, not invasion and conquest.111 The supposed discovery of female

warriors among the barbarian dead in northern Italy should be

treated as sensationalism, not good history, and should not lead us

to conclude that whole peoples were on the march in a search for

land.112 The Empire’s ‘enemies’ at this time consisted of communities

which had long lived close to it in relative harmony. If their young

men did turn to what amounted to intense banditry in this period,

the cause may have been much more close to hand than pressure

from the interior. Given the close relationship between the Danube

communities and the Roman army, the mass movement of troops to

107 e.g. below 121, 207.

108 Again, chronology of this is much disputed: see, e.g. Garzetti (1974: 486, 490)

gives ad 167, possibly 169; Birley (1987: 250–2) gives ad 170.

109 Garzetti (1974: 483–4); Birley (1987: 148 (quotation), 155, 253–5). Cf. the

criticisms of Burns (2003: 235).

110 Birley (1987: 148–9).

111 Garzetti (1974: 486).

112 Thus, contra Birley (1987: 169). Cf. Zonaras 12.23: the discovery of women’s

corpses among Persian dead in 260.

30 Prelude

the east to Wght the Parthian war and their return infected with

disease could well have spelled social and economic disaster.113 Raid-

ing was an alternative means of sur vival, and would have been made

easier by the depletion of the frontier garrisons. But, in the mid-160s,

raiding drew imperial attention and resulted in a build-up of imper-

ial forces clearly intent on aggression. No wonder that some Quadi

and Marcomanni panicked and attacked Wrst. And no wonder that

Roman forces, expecting relatively easy victory, were surprised and

let them through. The invasions of Italy and Greece should never

have happened. But the basic weakness of the Empire’s Germanic

enemies is shown in how quickly Rome was able to restore the

situation, and take the oVensive. Again, Rome was the aggressor

here: Marcus Aurelius was set on annexing new territories.114

The Wrst phase of the Marcomannic Wars, from 168–75, was

therefore not fought by an Empire on the defensive. The decisive

incident was the ‘invasion’ of Italy—humiliating in itself and raising

memories of the Cimbri, and even of Brennus. The second phase,

from 178–80, followed exactly the same pattern, as Marcus, obstin-

ately fulWlling his duty, returned to Wnish what had been interrupted

by revolt. Now, however, there was an additional, more conventional,

factor in play. The young (he was born in 161) Commodus’ formal

acceptance as heir had been accelerated to meet the challenge of

Avidius Cassius, and as part of this process he needed to be accepted

by the army. The second phase, like the Wrst, was characterized by

Roman aggression and military superiority.115 Birley describes the

conXict as ‘a grim and sordid necessity’; but it was necessary only

because Marcus regarded it as such. There appear to have been

numerous opportunities for a negotiated peace, but these he chose

to ignore.116 Again as in 16 bc, there was a ‘threat’ on the Danube in

the 170s but it was Roman, not Germanic.

Following Commodus’ departure from the northern frontier, there

was peace with the Germani for several decades. Even prolonged

Roman political instability and civil war, prompted by the assassin-

113 Burns (2003: 229–35); cf. below 49, n. 36.

114 Birley (1987: 142, 163, 183, 207, 209, 253); Isaac (1992: 390–1).

115 See Birley (1987: 207–9).

116 See, e.g. Birley (1987: 155–6, 169–70).

Prelude 31

ation of Commodus at the end of 192 and leading to the accession of

Septimius Severus (193–211), did not provoke signiWcant raiding. In

213, Severus’ successor, his son, Caracalla (211–17), made contact

with ‘Alamanni’ on the middle Main, which is when the following

chapter begins.

The preceding account of Roman dealings with western Germani is

based on the literary sources. It can be supplemented from archaeo-

logical research. The course of the Augustan and Tiberian campaigns

can be reconstructed through the study of right-bank forts and

marching-camps, etc.117 However, these were temporary and, with

the exception of certain sites (in particular, that of Waldgirmes), will

not be considered further here. More important is what came later—

above all the development of the security line across the re-entrant

angle of the upper Rhine and upper Danube, now termed the ‘Upper

German/Raetian limes’. 118

Although imperial troops w ithdrew to the left bank of the Rhine

after the Varus disaster, it is unlikely that they abandoned the right

bank for any length of time. As early as Tiberius, a permanent Roman

bridgehead was established in Chattian territory at Hofheim, oppos-

ite Mainz; and the Roman military presence in this region appears to

have been strengthened under Gaius.119 Under Claudius, this area

saw the opening of a silver mine near Wiesbaden, beginning imperial

exploitation of transrhenish resources that continued into the

fourth century.120 The main advance, however, came under the

Flavians. Vespasian moved into the area north of the lower Main,

the Wetterau, and into the Neckar valley, and drove a road from the

Rhine to the Danube. In the course of his conXict with the Chatti,

Domitian built a set of defended roads in the Wetterau. He consoli-

dated Roman presence on the Neckar, and threw open the land

117 The classic study remains Wells (1972).

118 Cf. below 50. I recognize the great problems involved in using limes as a

synonym for defended frontier line (see Isaac (1992: 408–9)) but, like other equally

questionable terms (such as ‘Romanization’), it is too useful a piece of historical

shorthand to give up.

119 Drinkwater (1983a: 36); Barrett (1989: 131). Schnurbein (2003: 104) suggests

the re-establishment of a Roman presence in the area before the death of Augustus.

120 Tacitus, Annales 11.20.4: in agro Mattiaci. Cf. below 133.

32 Prelude

between the Rhine and the Neckar, the Agri Decumates, to colonists

from Gaul.121 By 100, the protection of Roman territory south of the

Main was centred on the Neckar and the Swabian Alp.

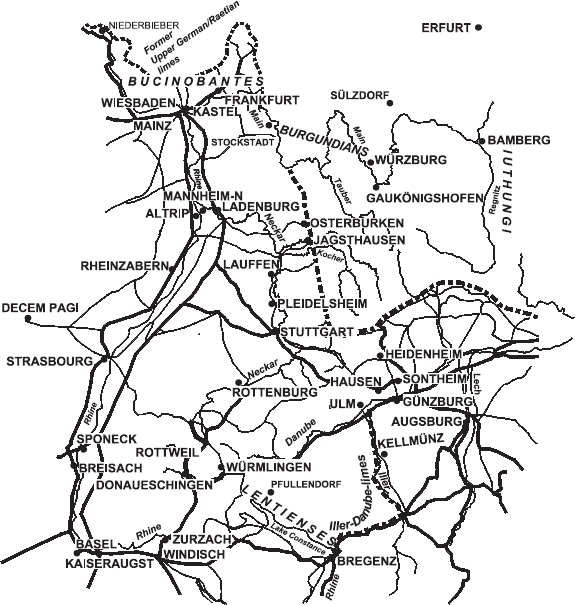

This remained the case until Antoninus Pius, when major change

came with the projection of the Upper German border c.30 km to the

east, its integration with the Raetian border, and the combined fron-

tier being delineated by a palisade. This line, from Miltenberg-Ost, via

Lorch, to the Danube near Eining, was given its Wnal shape w ith the

addition of a rampart and ditch backing onto the palisade in Upper

Germany, and the replacement of the palisade with a stone wall in

Raetia122 (Fig. 2). The Upper German/Raetian limes was now in

existence. Its most signiWcant aspect is its vulnerability. Laid along

two intersecting straight lines, it totally disregarded tactical topo-

graphy, and appears to have been created more for show than for use.

It could have oVer ed little direct resistance to a large force of determined

attackers.123 As a military installation it could meet, at best, in

Luttwak’s terms, ‘low intensity’ threats posed by ‘transborder inWltra-

tions and peripheral incursions’, that is raiding, banditry.124 In short,

it appears to reXect a lack of danger from the Germani whom it faced.

How does such an assessment of the Upper German/Raetian limes

square with what we can say about these Germani? Roman militar y

activity may be reconstructed from both texts and artefacts. Ger-

manic settlement is accessible only through archaeology, and early

Germanic archaeology is, as ever, very diYcult.125 However, it has

long been thought that, although there was a strip of Germanic

settlements along the right bank of the Lower Rhine, their main

concentrations lay much further in the interior.126 Of special signi-

Wcance for Alamannic studies is the fact that surprisingly few such

settlements have been found skirting the Upper German/Raetian

limes. To explain this, it has been suggested that the Romans simply

121 Drinkwater (1983a: 57–60); below 126.

122 For further details see Baatz (1975: 16, 58–62); Drinkwater (1983a: 60–3);

Carroll (2001: 38–9).

123 Cf. Isaac (1992: 414); Whittaker (1994: 84); Witschel (1999: 204).

124 Luttwak (1976: 66); cf. Baatz (1975: 44); Drinkwater (1983a: 64). For low-level

raiding as banditry, see Elton (1996a: 62).

125 See Schnurbein (2000: 51–3); cf. above 4, and below 112.

126 e.g. Baatz (1975: 49–50 and Fig. 29) (¼Whittaker (1994: 89 and Fig. 22)).

Prelude 33

appropriated all the best land in the region.127 Thanks to recent

research, we are now in a position to check both the general settle-

ment pattern and the thinking it has generated.

A stretch of early Germanic settlement along the northern bank of

the middle Lahn has recently been subjected to close scrutiny128

(Fig. 3). Like the neighbouring Wetterau,129 this region appears to

have been subject to continuous settlement from the Celtic Late Iron

Age into the Germanic period. It was not inferior land. Indeed, it has

been suggested that Wnds of local non-Roman coinages at major

Roman sites (in particular, Waldgirmes) built in the region under

Augustus indicate the presence of relatively sophisticated Germanic

Area of box

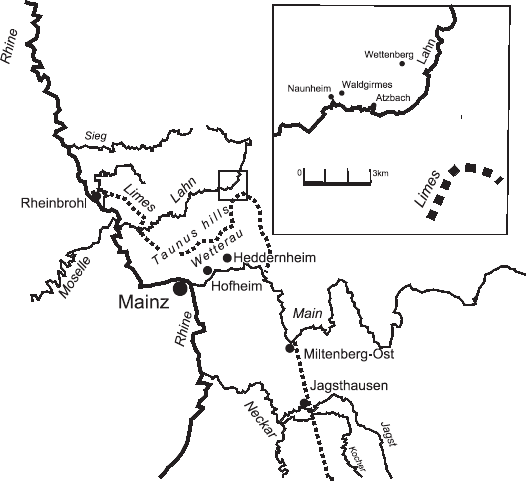

Fig. 3 The Lahn and Wetterau regions [after Abegg-Wigg, Walter, and

Biegert (2000: 57 Fig. 1)].

127 Whittaker (1994: 89).

128 For this,and the bulk of what follows, seeA. Wigg (1997)and Abegg-Wigg, Walter,

and Biegert (2000). For a useful English summary of the work, see A. Wigg (1999).

129 Lindenthal and Rupp (2000); Scholz (1997); Stobbe (2000).

34 Prelude

communities that had adopted important aspects of Celtic economic

and social behaviour.130 The earliest Germanic presence was short-

lived—disappearing early in the Wrst century ad after the Varus

disaster, along with the Roman garrisons. Users of Germanic

‘Rhine–Weser’-style artefacts returned at the end of the same century,

that is at the same time as the development of the Wetterau limes.

The key archaeological sites are at Naunheim, Wettenberg and

Lahnau. Ceramic remains indicate that their inhabitants imported

goods from the Empire, whose border lay, at its closest point, just

15 km (9 statute miles) to the south.

However, the middle Lahn remains one of only three known areas

of Germanic settlement on the northern half of the Upper German/

Raetian limes (the c.300-km (180-mile) stretch between Rheinbrohl

and Jagsthausen).131 Of the rest, the two nearest to the study area lie

20 km (12 statute miles) to the north-west and 40 km (24 statute

miles) to the north-east respectively. In other words, the most recent

archaeological work appears to conWrm sparsity of Germanic settle-

ment close to the limes. Next to be noted is that importation of

Roman-style artefacts took around 50 years, deep into the second

century, to become signiWcant. And, even then, the proportion of

such artefacts found on the Lahn sites is small, with little metal and

glass and relatively small amounts of pottery. There is no sign of

‘technology transfer’, that is styles and methods of production of

Roman artefact forms being taken up by Germani. Further, analysis

of Roman and indigenous wares suggests that though Germani may

have imported some exotic foodstuVs, they made no fundamental

changes to the content, preparation and presentation of their meals.

This is conWrmed by study of the animal and plant remains, which

indicates direct continuation of Late Iron Age agricultural patterns—

quite diVerent from the neighbouring Wetterau where, for example,

cattle gave way to pigs as Romanized settlers from Gaul further

developed the land.132 Finally, despite their proximity to the Empire,

there is no indication that the middle-Lahn Germani were par t of the

imperial monetary economy.

130 Wigg (2003). For reconstruction of the evolution of Wigg’s ‘Germanic’ coinage

from Celtic models, and its destruction by Drusus’ campaigns, see Heinrichs (2003).

131 Abegg-Wigg et al. (2000: 56).

132 Stobbe (2000: 216).

Prelude 35

Similar mixed results have come from study of the middle Main,

centred on the prehistoric settlement of Gauko

¨

nigshofen, south of

Wu

¨

rzburg133 (Fig. 4). Again we see continuity of settlement from the

Celtic Late Iron Age into the early Germanic period, with the Wrst

Germanic settlement being contemporary with Augustan expansion

into Germania, and close contact between these earliest Germani and

the Roman army. Again, too, there was a break at the beginning of the

Wrst century, followed in the mid-second century by the arrival of

Rhine–Weser artefact-users at the same time as the Wnal advancing of

the limes line. The same period also saw Germanic settlement on the

Tauber.134 Roman products—represented by ceramics—were

imported from Upper Germany and Raetia, though more from

the former than the latter. Roman inXuence has been detected in

the possible use of coins in trade, and in local house-building tech-

niques.135 There is also a case for believing that local Germani

introduced Roman cattle/oxen as draught animals. And this is one

of the areas where, in the third century, there was production of

Roman-style wheel-thrown pottery (‘the Haarhausen–Eßleben ex-

periments’).136 On the other hand, the imported pottery was

restricted to certain main lines and, oddly, in the light of the later

strategic importance of the river, appears to have come by land, from

the limes line, via Osterburken or Jagsthausen, not by water, up the

Main.137 Again there is little sign of such inXuence on the preparation

and serving of food and drink (everyday and as part of rituals). And

the pottery experiment was exceptional and short-lived, probably

because it was dependent on Roman captives.138 Further aWeld across

Franconia, Germanic sites of the period of the Early and High Roman

Empire generally show no long-term adoption of Celto-Roman

agricultural methods. Even at Gauko

¨

nigshofen, the introduction of

Roman stock produced no permanent improvement in local breeds.139

133 See, generally, for what follows Steidl (1997), (2000).

134 Frank (1997); Steidl (2000: 107, Fig. 9).

135 Coins: Steidl (1997: 76). Cf. below 135, for the continuation of coin use into

the fourth century. House-building: Steidl (2000: 104–5).

136 Below 92.

137 Steidl (2000: 106); cf. below 99, 113–15, 131–2, 190.

138 Steidl (2000: 106, 109). Below 92–3.

139 Benecke (2000: 253).

36 Prelude

Fig. 4 Alamannia.

Prelude 37