Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

cityscape and provided destinations for citizens in motion. Urban networks make

tangible past choices as they mould present interactions. The reshaping of geo-

graphical landscapes in Britain has operated through the interconnections of an

urban hierarchy solidified by the combined investments of state and industry in

a century of rapid growth and change.

Lynn Hollen Lees

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

·

·

Modern London

It is difficult to speak adequately or justly of London. It is not a pleasant place; it is

not agreeable, or cheerful, or easy, or exempt from reproach. It is only magnificent.

You can draw up a tremendous list of reasons why it should be insupportable . . .

But . . . for one who takes it as I take it, London is on the whole the most possible

formoflife...Itisthebiggest aggregation of human life – the most complete

compendium of the world. The human race is better represented there than any-

where else, and if you learn to know your London you learn a great many things.

Henry James,

1

D

essence of modern London into a chapter, one cannot

help but be selective. I will focus on just four, interrelated aspects of

London’s history: government, social geography, economy and

Empire.

2

It is clearly impossible to understand London without examining the

‘problem’ of London’s government: the relationship between central govern-

ment, the Corporation of the City, London-wide authorities such as the

Metropolitan Board of Works and its successor, the London County Council,

and lower-tier authorities, initially parish vestries and district boards and, subse-

quently, metropolitan borough councils. But making sense of debates about

appropriate forms of metropolitan government demands a sensitivity to

London’s changing social geography: a nineteenth-century tension between

poor East End and rich West End, subsumed in a twentieth-century contrast

1

F. O. Matthiessen and K. B. Murdock, eds., The Notebooks of Henry James (New York, ), pp.

–.

2

At the outset it is worth noting two valuable bibliographic essays: J. Davis, ‘Modern London

–’, LJ, (), –, and M. Hebbert, ‘London recent and present’, LJ, (),

–. For a comprehensive listing of published work on London history, see H. Creaton, ed.,

Bibliography of Printed Works on London History to (London, ). See also three general his-

tories of London, all with detailed notes and/or bibliographies: R. Porter, London (London, );

S. Inwood, A History of London (London, ); F. Sheppard, London (Oxford, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

between working-class inner and middle-class outer London. Of course there

are numerous qualifications to be made to this caricature, to take account of

working-class suburbanisation, the survival of an elite West End and, more

recently, a sporadic gentrification of inner London, and a City that shifted from

mixed residential to almost exclusively non-residential in its pattern of land use.

Alongside these socio-geographical changes there were also major economic

changes: decline of some traditional industries, growth of a service economy and

especially of the City as centre of world finance, and interwar manufacturing

revival, but in an Americanised and suburban form. Even in the nineteenth

century social differentiation was increasing at the same time as the metropolis was

becoming economically more integrated. This was also evident in London’s con-

tinuing evolution as a centre of elite consumption – as reflected in the aristocratic

‘season’ and its extension into a nouveau riche world of grand hotels, restaurants,

clubs and theatres – which necessarily depended on low-paid, seasonal and casual

labour working what today would be regarded as ‘unsocial hours’. So a chapter

on London must also pay attention to the city’s economy, and to the relationship

of London with the rest of the world, especially its role as ‘Heart of the Empire’.

Before we can concentrate in detail on these four themes, several other ques-

tions merit our attention. First, with regard to the definition and ‘knowability’

of London.

3

The census first defined a London that was larger than the square

mile of the City in . This definition provided the boundary for both the

Metropolitan Board of Works, in , and the County of London, in . But

the built-up area of London had burst through this boundary long before .

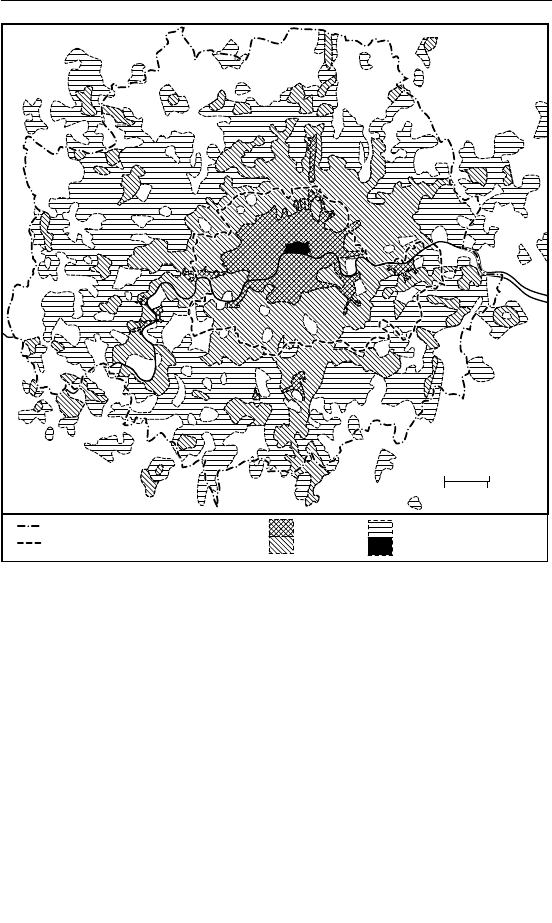

‘Greater London’ came to be defined statistically in the s as equivalent to

the Metropolitan Police District, extending miles ( km) from Charing

Cross (Map .).

4

Although London might be seen as one organic growth,

unlike other ‘conurbations’ that linked several cities of roughly equal impor-

tance, its expansion embraced some quite substantial, previously independent

settlements. The issue of ‘localism’ versus ‘metropolitanism’ continues to the

present – do Londoners think of themselves as Londoners, or do they identify

with their local borough, or parish; or are all these administrative units artificial

impositions cutting across an allegiance to no more than the immediate neigh-

bourhood? To Roy Porter, London is a jigsaw, ‘a congregation of diversity’ in

which the absence of strong metropolitan-wide government meant that ‘confu-

sion permitted diversity and interstitial growth’, almost a postmodern celebra-

tion of an unorganised if not disorganised metropolis.

5

Secondly, we may question the existence of ‘turning points’ in the history of

Richard Dennis

3

On ‘knowability’ see M. Hebbert, London (Chichester, ), esp. ch. , ‘The knowledge’.

4

P. J. Waller, Town, City and Nation (Oxford, ), pp. –; P. L. Garside, ‘West End, East End:

London, –’, in A. Sutcliffe, ed., Metropolis, – (London, ), p. .

5

Porter, London, pp. , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

London. Asa Briggs focused on fin de siècle London as a moment when the

metropolis particularly exemplified British history.

6

Pat Garside identified criti-

cal boundaries at and , perhaps implying that the whole intervening

half-century was one long turning point. Prior to , according to H. J. Dyos’

view, ‘London was, at one and the same time, central yet peripheral, economi-

cally secondary yet socially dominant, culturally inspirational yet parasitic.’

Modifying this interpretation, Garside concluded that ‘London’s economic

achievements in the mid-nineteenth century were not derived from, nor even

interdependent with provincial manufacturing towns: it was neither parasitic nor

ambiotic – it was separate, self-generating and highly successful.’ None the less,

there was a strong relationship between London and the provinces, in flows of

Modern London

6

A. Briggs, Victorian Cities (London, ), pp. –.

0

0

5 km

3 miles

1850

1914

Metropolitan Police District

London County Council

1960

City of London

Map . The boundaries and built-up area of London –

Source: modified from H. Clout and P. Wood, eds., London (Harlow, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

both labour and capital, especially for infrastructural projects such as railways,

and specialist financial and insurance services. By contrast, after , ‘London’s

own domestic problems were to force themselves forward as the national issues

of the moment.’ National policies were designed to solve metropolitan

problems.

7

The period between and may be considered transitional particu-

larly because of the city’s novel demographic experience, losing population

across an ever wider central area at the same time as it was growing physically

and numerically at the periphery. Until , ‘Greater London’ grew at a faster

rate than England as a whole. Until , even the area subject to the

Metropolitan Board of Works (later the County of London) was gaining popu-

lation more rapidly than England, but from to , the County grew more

slowly than the rest of the country. After , the LCC area started to lose pop-

ulation, such that ‘Greater London’ as a whole failed to keep up with the pop-

ulation growth of the rest of the country, and the proportion of the country’s

population resident in London peaked in at . per cent. The City, of

course, had long been in rapid decline as a place of residence: , residents

in , , sixty years later.

8

After the First World War, the County continued its gradual population

decrease, but outer London now grew so rapidly compared to the sluggish

increase elsewhere that in the s population growth in ‘Greater London’once

again outstripped the rate for England and Wales. Contemporaries concluded

that by London’s dominance was contrary to the national interest.

Compounding the interpretation of earlier observers, such as William Cobbett,

that London was a cancerous growth on the body of the nation, there was now

the fear that increasing geographical concentration of wealth and population

made the nation more vulnerable to air attack in time of war.

9

But, in most

respects, as David Feldman and Gareth Stedman Jones observed, the capital’s

primacy was just one of the ‘striking regularities and recurrences in London’s

history’. Continuing debates about racism and immigration policy can be com-

pared with agitation that prompted the passage of the Aliens Act in , a piece

of national legislation primarily intended to deal with a London problem; and

modern ideas of ‘underclass’ and ‘culture of poverty’ parallel the Victorian

concept of the residuum.

10

Porter, too, points to a congruence between late

nineteenth- and late twentieth-century London, for example comparing the

diagnoses offered by Mearns’ Bitter Cry of Outcast London and the Church of

Richard Dennis

17

The quotations are all from P. L. Garside, ‘London and the Home Counties’, in F. M. L.

Thompson, ed., The Cambridge Social History of Britain, –, vol. : Regions and Communities

(Cambridge, ), pp. , , .

8

Waller, Town, pp. –.

19

Garside, ‘London’, p. .

10

D. Feldman and G. Stedman Jones, ‘Introduction’, in D. Feldman and G. Stedman Jones, eds.,

Metropolis (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England’s Faith in the City.

11

Of course, there are also major differences: in

gender relations, in the role of women and as a consequence of the decline of

Empire. Such parallels and divergences illustrate how we constantly reinterpret

London’s history according to our own concerns, whether identifying the

origins of postmodern consumption practices in Victorian bazaars and depart-

ment stores, or re-evaluating the nineteenth-century manufacturing economy

in the context of more recent enthusiasm for ‘enterprise’ and ‘flexibility’.

(i)

Whatever else it may be, the period – constitutes the core of what

many cultural historians regard as ‘modern’. Writing about New York City in

the period –, David Ward and Olivier Zunz discuss modernity as the

combination of rational planning and cultural pluralism, the one creating order

– residential segregation, zoning, the efficient use of urban space – the other

reflecting the increasing diversity of urban populations.

12

To David Harvey,

order, mastery, rationality and planning are characteristics of the modern, in

contrast to the apparent chaos, relativism, diversity, even playfulness of the post-

modern.

13

But just as it has been argued that postmodernity is but a particular

kind of modernity, so we can envisage aspects of the postmodern in the modern

city of the late nineteenth century. For Marshall Berman, the roots of modern

urban life lie in the tension between enlightenment rationality and romanticism.

He traces the relationship between the discovery of self, self-knowledge and self-

identity on the one hand, and the organisation and ordering of society on the

other.

14

Berman’s argument, stressing the double-edged nature of modernity, provides

a framework for bringing together disparate themes in the history of London.

For example, we may set Charles Booth’s application of scientific principles to

survey, map and classify the people and places of London alongside George

Gissing’s novels which show how people experienced those places and con-

structed their own identities through their use of the city. We can interpret new

spaces – new streets like Charing Cross Road or Kingsway, new railway termini

and station hotels, department stores and chain stores, office blocks and facto-

ries, public parks and cemeteries, music halls and cinemas – as products of ratio-

nal planning and scientific management, but also as spaces for new kinds of

everyday life, and as potential spaces of resistance or subversion. James Winter

Modern London

11

Porter, London, pp. –.

12

D. Ward and O. Zunz, ‘Between rationalism and pluralism: creating the modern city’, in D. Ward

and O. Zunz, eds., The Landscape of Modernity (New York, ), pp. –.

13

D. Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity (Oxford, ), pp. –.

14

M. Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air (London, ), pp. –. For Berman’s ideas criti-

cally applied to England, see M. Nava and A. O’Shea, eds., Modern Times (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

has noted how ‘Straighteners, regulators, cleansers, purifiers, conservationists,

and promoters of the municipal ideal, liberals most of them, tried to balance

their vision of a London that was ordered, rational, efficient, healthy, and safe,

in other words, “modern”, with a sense that the freedom of the public thorough-

fare disclosed what it meant to be English.’ It proved difficult to reconcile ‘the

metaphor of reform and a liberal devotion to individual self-determination’.

15

This is clearly demonstrated in Susan Pennybacker’s analysis of the failures of

LCC ‘Progressivism’ prior to the First World War. Far from making space for

personal freedom and self-fulfilment, the Progressive programme of regulation

and classification, embodied in public health officials, moral guardians, park

keepers, housing managers and licensing authorities, and designed to counter

fears of moral and physical degeneracy, legitimated the eugenics movement and

alienated the lower middle classes. In Pennybacker’s words, ‘intrusion and super-

vision were substituted for grander programmes of social amelioration or cultu-

ral enlightenment’.

16

This is not to deny an inherent modernity, which predated and continued

independently of the attempts of a modern council to regulate its reluctant cit-

izens. London was ‘modern’ despite the absence of effective planning. Positing

London as much as Paris as ‘capital of the nineteenth century’, on the basis of

‘its exemplary individualism’, Richard Sennett has suggested, first, that the

power of great landowners, especially in the West End, contrasting with the

weakness of metropolitan government, facilitated the development of a city of

class-homogeneous but disconnected spaces. London was characterised by estate

planning rather than town planning. But London also appeared excessively

orderly to Sennett (who has long advocated the positive aspects of disorder)

because what ‘planning’ there was, in the form of new roads and new public

transport networks (buses, railways, trams), was designed to encourage the free

movement of individuals but discourage the movement of organised groups.

17

It distanced Londoners from the environments through which they passed.

Winter noted as much in discussing ‘why so many early Victorians came to

define the city as a circulatory system rather than a fixed place’. Medical meta-

phors alluded to the need to remove ‘arterial obstructions’. Hence the need to

regulate traffic – the first traffic signal erected experimentally, but soon aban-

doned, in Parliament Square, in , and the eventual introduction of traffic

lights in ; the appointment of traffic constables from – and an ambiv-

alence towards street furniture, like drinking troughs and urinals, which utilised

new technology in their manufacture but slowed down the flow of both horses

and pedestrians. Streets were where one ‘walked briskly’. Less purposive behav-

iour was condemned as ‘loafing’ or ‘sauntering listlessly’, or made one liable to

Richard Dennis

15

J. Winter, London’s Teeming Streets, – (London, ), p. xi.

16

S. D. Pennybacker, A Vision for London, – (London, ), p. .

17

R. Sennett, Flesh and Stone (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

prosecution under the Vagrancy Act, whereas the same behaviour in a park

would be tolerated as ‘strolling’ or ‘promenading’.

18

While new streets, railway lines and tramways made for faster, more purpos-

ive travel, other technological improvements made travel more comfortable. But

comfort is associated with rest. Movement became a more passive, as well as a

more private experience. Silence in travel was used to protect individual privacy.

So, Sennett concluded, drawing on Forster’s Howards End (), London

became ‘a city that seems to hold together socially precisely because people don’t

connect personally’.

19

The motto of Howards End was ‘only connect’, and the

interpersonal and cross-class connections that eventually occur, which allow

Forster’s characters to discover their own identities, are the results of displace-

ments and discord in their lives, occurrences which – for Sennett – were all too

rare in Edwardian London.

Howards End perfectly captures a dispirited view of London’s Faustian devel-

opment. Margaret Schlegel contemplated the demolition of her own home to

make way for a block of ‘Babylonian’ mansion flats: ‘In the streets of the city she

noted for the first time the architecture of hurry, and heard the language of hurry

on the mouths of its inhabitants – clipped words, formless sentences, potted

expressions of approval or disgust. Month by month things were stepping live-

lier, but to what goal?’When the Schlegels eventually achieved the promised land

of Howards End, an idyllic converted farmhouse in Hertfordshire, the shadow of

the metropolis was still there: ‘“London’s creeping.” She pointed over the

meadow – over eight or nine meadows, but at the end of them was a red rust.’

20

(ii) ’

In London still lacked any semblance of city-wide government. The City

Corporation was irrelevant as far as most of London was concerned, and the

Municipal Corporations Act had passed London by, though it could be argued

that some vestries were at least as efficient as some reformed corporations else-

where in the country. More often, London historians have condemned the ves-

tries as corrupt and apathetic, dominated by petty-minded tradesmen who

resented public spending. However suspicious of such assertions, we must

acknowledge that neither elite leadership nor participatory politics was very

evident in London’s local government.

21

Worries about public health did lead to some reforms – the creation of a

Metropolitan Commission of Sewers in and, in , the Metropolitan

Board of Works (MBW), its members elected by twenty-three ancient vestries

and fifteen new district boards which combined groups of small parishes. Briggs

Modern London

18

Winter, London’s Teeming Streets, pp. , –, –.

19

Sennett, Flesh, p. .

20

E. M. Forster, Howards End (London, ; Penguin edn), pp. –, .

21

J. Davis, Reforming London (Oxford, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

claimed that the area governed by the MBW was determined more by the exist-

ing network of drains and sewers than by any administrative logic, though a less

romantic explanation was that it corresponded to the registrar general’s

definition of London in the census. Despite its undoubted achievements –

Bazalgette’s sewers and the associated pumping stations, the Embankment,

Charing Cross Road, Shaftesbury Avenue and the beginnings of slum clearance

and rehousing – the indirectly elected MBW, packed with vestrymen of such

lengthy experience as to constitute a veritable gerontocracy, was a poor substi-

tute for democratic, London-wide government. Rejection of the latter by a royal

commission in , which claimed a lack of sufficient common interest among

inhabitants in different parts of the built-up area, represented a triumph for the

vestries. The royal commission had, however, suggested the creation of eight

large municipalities corresponding to the eight parliamentary boroughs into

which the metropolis was then divided, but this too had been turned down on

the grounds that they would be too large for effective local government.

22

When the London County Council eventually came into being as a product

of the Local Government Act, its powers were still quite limited. It had no

control over the police, who remained under Home Office authority, or educa-

tion (which was the responsibility of the London School Board), or administra-

tion of the poor law; and it inherited the Board of Works’ boundaries, which

were now even more illogical, given the physical growth of the metropolis since

. From the beginning, therefore, almost all of London’s population growth

occurred beyond the boundaries of the new county; and from onwards,

the population of the LCC area was in decline. The LCC was established by a

Conservative central government, but at the first – now direct – elections, a

Liberal-Progressive majority was returned, which retained control until .

Lord Salisbury anticipated that the radicals would soon lose popular support, but

when this failed to occur, the Conservative-sponsored London Municipal

Society was formed to press for decentralisation of the Council’s powers to a

strengthened lower tier of municipal authorities. The result was the balancing of

the LCC by twenty-eight metropolitan boroughs, an arrangement that contin-

ued from into the s.

23

What was the effect of this arrangement on the LCC, and how far did local

populations identify with the new boroughs? According to Garside

In practice, the new structure did not diminish the power of the LCC. Indeed, it

could be argued that the LCC’s broader vision was strengthened. With the met-

ropolitan borough councils offering a focus for parochial pride, the LCC could

more easily insulate itself from local interests, projecting and developing a London-

wide base as a framework for policy and decision-making.

24

Richard Dennis

22

Briggs, Victorian Cities, p. ; D. Owen, The Government of Victorian London, –

(Cambridge, Mass., and London, ); Davis, Reforming London.

23

K. Young and P. Garside, Metropolitan London (London, ), pp. –, .

24

Garside, ‘London’, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Yet the LCC’s record does not really bear out this strategic role. The Council

eventually took control of education, trams and poor law infirmaries. By the

s, it owned bridges and tunnels across the Thames, miles of

tramway, parks, fire stations, mental hospitals, and more than ,

schools. Nevertheless, housing apart, the LCC did little to change the physical

structure of London. For example, it laid out far fewer new streets than its sup-

posedly lethargic predecessor, the Metropolitan Board of Works;

25

and the

Labour-controlled LCC after showed no interest in planning that extended

beyond its county boundaries. Wider proposals for regional planning were con-

demned by the chairman of the LCC Town Planning Committee as ‘fascist’ and

‘un-British’.

26

It is difficult to see how the LCC could plan with much vision

when it only had responsibility for the declining inner parts of a rapidly expand-

ing whole.

As for the new boroughs, there was some scepticism as to whether their res-

idents would identify with them. H. G. Wells claimed that localism was being

eroded by every new form of communication. Philip Waller observes that ‘Civic

pride in most London districts had to be contrived.’ Londoners naturally

identified with localities, not with boroughs. Yet in some cases, the construction

of local identity was remarkably successful: for example, in the socialist fiefdoms

of Poplar and Bermondsey.

27

For Wells the solution to London’s problems lay in a ‘Greater London’ that

would embrace the entire commuting population of the Home Counties. Part

of the logic underlying the creation of the LCC had been the need to equalise

rates between poor and rich districts, such that the West End would contribute

to solving the problems of the East End. Geographically, too, the problems of

poor districts were not to be solved in situ but elsewhere, in suburbs that lay

outside the County of London. In the richest parish – St James, Piccadilly

– had a rateable value per head that was nearly seven times that of the poorest

parish – Bethnal Green. To yield an equivalent income, a much higher rate in

the pound had to be levied in poor areas. East End vestries also complained that,

although they contributed on an equal basis to the MBW, most of the Board’s

expenditure was concentrated in central London. By , the gap had widened:

St Martin-in-the-Fields had a per capita valuation thirteen times that of Mile

End.

28

By then a programme of rate equalisation and fiscal integration of the

City and second-tier authorities had been implemented, but most suburbs with

Modern London

25

Porter, London, p. .

26

Garside, ‘West End’, p. .

27

Waller, Town, p. ; for Wells, see Porter, London, p. , Garside, ‘West End’, pp. –; on

Poplar, see J. Gillespie, ‘Poplarism and proletarianism: unemployment and Labour politics in

London, –’, in Feldman and Stedman Jones, eds., Metropolis, pp. –, G. Rose,

‘Locality, politics, and culture: Poplar in the s’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space,

(), –, G. Rose, ‘Imagining Poplar in the s: contested concepts of community’,

Journal of Historical Geography, (), –; on Bermondsey, see E. Lebas, ‘When every street

became a cinema: the film work of Bermondsey Borough Council’s public-health department,

–’, History Workshop Jour nal, (), –.

28

Davis, Reforming London, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008