Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

land to spare and many of the more prosperous middle classes lay beyond the

boundaries of the LCC. The Council did have rights to acquire land and develop

housing estates outside the County, but the consequence was usually to antag-

onise out-county authorities who liked to think of themselves as definitely not

London.

Unsurprisingly, it proved impracticable for the County to expand. After ,

the urgency of the housing crisis led to shelving of proposals to reform London

government, at the expense of striking local bargains with individual out-county

authorities prepared to accept LCC housing. But the sight of these new ‘Labour

colonies’, growing up in the fields of Essex, Kent, Surrey and Middlesex,

strengthened the resolve of suburban authorities as a whole not to succumb to

a ‘Greater London’.

29

One consequence of the continued growth of privately developed, owner-

occupied suburbs was that the inner city became more solidly working class. This

did not necessarily equate with support for Labour; there was always a strong

strand of working-class Toryism, and also the growth of Fascism in parts of the

East End in the s. But from Labour assumed control of the LCC. For

Conservatives this heralded a return to the fears of the s: a strong left-leaning

municipality challenging the authority of central government. Their solution

after the Second World War was to decentralise as much as possible to the bor-

oughs and, reluctantly, acknowledge the need for a modest ‘Greater London’ in

which the weight of suburbia might restore Conservative control; but not as

great a ‘Greater London’ as Wells had envisaged, because such a regional scale of

government, even under the Conservatives, would have presented too great a

threat to Whitehall. In sum, London government through the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries has been a curious mixture of centralised and decentralised,

elected and unelected, visionary and routine, a very ‘modern’ combination of

order and diversity.

30

(iii)

The scale and character of residential segregation in London was one conse-

quence of its size. Where, in provincial cities, there might be groups of streets,

or neighbourhoods, associated with one social or ethnic group, in London –

especially in suburban London – there could be whole boroughs in which one

class predominated. There was also scope for more gradations in the social hier-

archy to be expressed topographically, for example for subtle variations to exist

Richard Dennis

29

Garside, ‘West End’, pp. –.

30

Young and Garside, Metropolitan London, pp. –, –; Porter, London, pp. –; C.

Husbands, ‘East End racism, –’, LJ, (), –. On the history of the LCC, see also

A. Saint, ed., Politics and the People of London (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

between estates within lower-middle-class suburbia. A particularly sensitive

observer was the novelist, George Gissing. Whereas Wells and Forster wrote

about types of places, or at least changed the names to imaginary ones, Gissing

often wrote about real streets.

In In the Year of Jubilee (, but set in and the years immediately fol-

lowing), much of the story is set in what for urban historians is the Victorian

suburb: Camberwell.

31

When the honest but dull Samuel Barmby became a

partner in a local piano business, his family moved to Dagmar Road, ‘a new

and most respectable house, with bay windows rising from the half-sunk base-

ment to the second storey. Samuel...privately admitted the charm of such

an address as “Dagmar Road”, which looks well at the head of note-paper, and

falls with sonority from the lips.’ Less than five minutes’ walk away, the

Peacheys occupied a villa in De Crespigny Park. Again, the house matched the

family. Arthur Peachey was in the business of manufacturing a disinfectant, sub-

sequently proved to be worthless, adulterated, possibly even harmful; the rest

of his family were revealed as equally shallow and suspect. As for their home,

it was ‘unattached, double-fronted...aflight of steps to the stucco pillars at

the entrance’. Each house in De Crespigny Park ‘seems to remind its neigh-

bour, with all the complacence expressible in buff brick, that in this locality

lodgings are not to let’. Yet higher, both physically and socially, was the resi-

dence of Mr Vawdrey, a wealthy City investor, on Champion Hill, ‘a gravel

byway, overhung with trees; large houses and spacious gardens on either hand

. . . One might have imagined it a country road, so profound the stillness and

so leafy the prospect.’

32

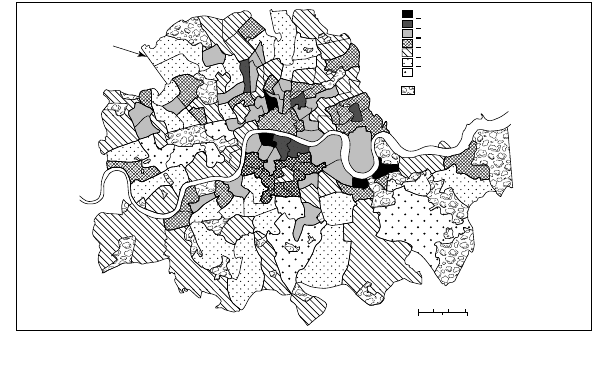

What Gissing depicted in words, Charles Booth painted on the map. Booth’s

portrayal of Life and Labour of the People in London began in , with a detailed

survey of the East End, based on the reports of school board visitors. Booth’s

classification of households into one of eight poverty classes facilitated the con-

struction of a poverty map, showing the percentage of households in the four

poorest classes in each part of the metropolis (Map .). Alongside this summary

map, he also produced a ‘Descriptive map of London poverty’ in which each

street was assigned to one of seven colours, ranging from the black of the ‘Lowest

class. Vicious, semi-criminal’ to the gold of the ‘Upper-middle and Upper

classes. Wealthy’. Although Booth’s focus was on the poor, and most commen-

tators have concentrated on his explanations for poverty and on the somewhat

ambiguous relationship between his classifications of households and streets

within the four poorest classes, his survey also distinguished between grades of

suburban respectability. De Crespigny Park and Champion Hill were both gold,

while Dagmar Road was the red of the ‘Middle class. Well-to-do’; but adjacent

Modern London

31

H. J. Dyos, Victorian Suburb (Leicester, ).

32

G. Gissing, In the Year of Jubilee (London, ; Everyman edn), pp. , , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Parks / open space

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

Limit of LCC

s

e

m

a

h

T

r

e

v

i

R

Percentage of the

population living in

poverty

012

0 1 2 miles

3 km

Map . Charles Booth’s poverty map of London

Source: H. Clout, ed., The Times London History Atlas (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Palace Gardens

St James' Park

Buckingham

Palace

Buckingham

Palace

Wellington Barracks

B

I

R

D

C

A

G EWALK

J

A

M

E

S

S

T

R

E

E

T

P

A

L

A

C

E

S

T

ROYAL

MEWS

EBURY STREET

BUCKI NGHAM PA

LACE ROA

D

VICTVICTORIA

STSTATIONTION

VICTORIA

STATION

CARLISLE ST

V ICTORIA

BREWERY

PHILLIP

STREET

ROCHESTERROW

MEDWAY ST

STREET

G

R

E

A

T

C

H

A

P

E

L

S

T

.

TOTHILL STREET

Y

O

R

K

S

T

GT GEORGE S T

T

H

E

S

A

N

C

T

U

A

R

Y

WESTMINSTER

ABBEY

DEAN'S

YARD

MARSH AM STREET

GAS

WORKS

9

3

2

Royal

Aquarium

Hotel

1

4

7

8

5

H

Wealthy. Upper-middle and upper classes.

Churches

Well-to-do. Middle class.

Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings.

Metropolitan District Railway

Hospital

Mixed. Some comfortable, others poor.

Poor. 18s to 21s a week for a moderate family.

Very poor, casual. Chronic want.

Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal.

1 Peabody Trust: Brewer's Green

2 Peabody Trust: Old Pye Street

3 Peabody Trust: Abbey Orchard Street

4 Army and Navy Stores

5 Carlisle Place (flats)

6 Queen Anne's Mansions

7 Prince's Mansions

8 Grosvenor Mansions

9 Westminster Chambers (offices)

H

0

0 100

200

300 yds

100 200 300 m

6

Map . Victoria Street : extract from Charles Booth’s descriptive map of London poverty

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

streets were only ‘Fairly Comfortable’ and there were pockets of poverty close

to Camberwell Green.

33

Booth’s project has attracted a range of critical evaluations. Christian Topalov

discusses Booth’s survey, and especially his mapping, as a new and ‘modern’ way

of seeing, arguing that ‘the social map owed something both to “slumming”, in

its attention to social types, and to the panorama in its global vision of the city’.

While acknowledging all the subjective aspects of Booth’s method of gathering

data and of his techniques of mapping, we can recognise the scientific objectives

of his survey, contrasting with the anecdotal or picaresque travellers’ tales of

earlier social explorers. Booth was not just exploring; by classifying and

mapping, he was equivalent to a colonial power, with a panoptic vision of the

city as a whole. Topalov notes that his poverty maps offered a vision of ‘the city

of the poor and the city of the rich united within a single space, shown as a

whole and therefore open to a coordinated administration’. So, ‘when the

L.C.C. began work, in , Booth’s map was in its in-tray’.

34

At the conclusion of Gissing’s novel, Nancy Tarrant moved across London to

Harrow, as remote from Camberwell, morally and culturally, as it was geograph-

ically. Compared to the sham pretentiousness of houses in Camberwell, those in

the street to which Nancy moved were ‘small plain houses, built not long ago,

yet at a time when small houses were constructed with some regard for sound-

ness and durability. Each contains six rooms, has a little strip of garden in the

rear, and is, or was in , let at a rent of six-and-twenty pounds.’

35

But Harrow

was now convenient for London, thanks to the opening of the Metropolitan

Railway from Baker Street, which had reached as far as Pinner by .

36

In

another of Gissing’s novels, The Whirlpool (), the respectable Harvey Rolfe

and his fragile wife, Alma, take a three-year lease on a new house in Pinner,

Harvey judging that ‘for any one who wished to live practically in London and

yet away from its frenzy, the uplands towards Buckinghamshire were convenient

ground’.

37

Subsequently, many other Harvey Rolfes opted for the convenience

of Metroland. The Metropolitan Railway first established its own development

company, promoting an estate in Pinner, then, in , began publication of its

Richard Dennis

33

C. Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London, vols. (London, –); for selected extracts,

see A. Fried and R. Elman, eds., Charles Booth’s London (London, ); for the original London-

wide poverty maps, D. Reeder and the London Topographical Society, Charles Booth’s Descriptive

Map of London Poverty (London, ).

34

C. Topalov, ‘The city as terra incognita: Charles Booth’s poverty survey and the people of

London, –’, Planning Perspectives, (), . See also M. Bulmer et al., eds., The Social

Survey in Historical Perspective, – (Cambridge, ); D. Englander and R. O’Day, eds.,

Retrieved Riches (Aldershot, ).

35

Gissing, Jubilee, p. .

36

A. A. Jackson, London’s Metropolitan Railway (Newton Abbot, ); T. C. Barker and M.

Robbins, A History of London Transport, vol. : The Nineteenth Century (London, ), pp. –.

37

G. Gissing, The Whirlpool (London, ; edn), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

annual Metro-Land guide, replete with advertisements from leading speculative

builders.

38

Working-class suburbanisation was more limited prior to the First World War.

In The Nether World (), Sidney Kirkwood and his wife attempted to escape

the oppressive poverty of Clerkenwell, where he worked as a manufacturing

jeweller, by moving to Crouch End. Kirkwood was following exactly the pattern

of out-migration prescribed by Booth. Better-off workers in regular employ-

ment (Booth’s Class E) were to move to the periphery, allowing the occupancy

of their old homes by those who were ‘immovable’. This was a geographically

extended version of what housing reformers referred to as ‘levelling up’. It had

the advantage of removing the respectable from the potential bad influence of

degenerate neighbours, although it also meant there was no hope of improving

the latter through the good example of the upwardly mobile.

39

However, there were few large-scale industrial suburbs in late Victorian

London, except in east and south-east London, where West Ham, Stratford and

Woolwich resembled northern industrial towns, occupied by an artisan elite,

mainly employed in large institutions such as Woolwich Arsenal, the Great

Eastern Railway works, and some of the food processing and chemical indus-

tries close to the Royal Docks and in the lower Lea valley. Self-help agencies that

characterised northern towns also flourished here: the Woolwich Building

Society dated from , the Royal Arsenal Co-operative Society from .

40

Most of Victorian and Edwardian suburbia was developed unplanned and

piecemeal by small builders: ‘in Camberwell, for example, as the local building

industry reached its peak between and , as many as firms, com-

prising per cent of the total at work in the area, built six houses or fewer over

this three-year period; only or less than per cent of the total, built over

houses each’. But by the s, these few large firms were responsible for about

one third of all new houses: Edward Yates, for example, built more than ,

houses in south London between the s and s.

41

There were also a few

examples of planned developments prior to the colonisation of the suburbs by

local authority housing estates. Bedford Park was laid out from the s as a

middle-class garden suburb; a generation later, Hampstead Garden Suburb was

Modern London

38

A. A. Jackson, Semi-Detached London, nd edn (Didcot, ), pp. , –; Metropolitan

Railway, Metro-Land (London, ; repr. ).

39

G. Gissing, The Nether World (London, ; Everyman edn), pp. –; Topalov, ‘The city’,

; on levelling up, see R. Dennis, ‘The geography of Victorian values: philanthropic housing

in London, –’, Journal of Historical Geography, (), –.

40

G. Crossick, An Artisan Elite in Victorian Society (London, ); J. Marriott, ‘West Ham: London’s

industrial centre and gateway to the world. : industrialisation, –’, LJ, (–),

–.

41

D. Cannadine and D. Reeder, eds., Exploring the Urban Past (Cambridge, ), pp. –,

–.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

envisaged by Henrietta Barnett as a socially mixed community, perhaps building

on her experience of East End settlement life, where the working classes were

supposed to benefit from the education, example and service of the rich. In prac-

tice, Hampstead Garden Suburb evolved as an exclusively middle-class area.

Three estates developed by the Artizans’, Labourers’ and General Dwellings

Company, at Shaftesbury Park (), Queen’s Park () and Noel Park

(), were more modest in intent, appealing to skilled working-class and lower

middle-class families.

42

The likes of Dagmar Road were still predominantly high-density terraced

housing. After the First World War, however, suburbia assumed a different char-

acter. Houses became smaller in floor area – usually only two storeys and no

basement – but front gardens were larger, and frontages were wider: the predom-

inant house type was semi-detached with side access and, by the s, space for

a garage. Between the wars the built-up area of London approximately doubled,

although population increased by little more than per cent. Whereas most

houses in Victorian Camberwell were rented from private landlords, interwar

suburbs were designed for owner-occupation. Building societies flush with

funds, cheap money, low building costs (thanks in part to an absence of planning

regulations), and the affluence of South-East England compared to the rest of

the country, all helped to facilitate suburban sprawl.

43

Privately developed, owner-occupied suburbia was particularly dependent on

further improvements in public transport. Some new ‘underground’ lines (in

practice, often overground by the time they reached suburbia) were financed as

public works projects for the unemployed: to Edgware (), Stanmore ()

and Cockfosters (). South of the river there was a major programme of

railway electrification, extending as far as Dorking by , and reaching to

Brighton in , and Portsmouth by .

44

Apart from council estates, interwar suburbs were mostly socially homogen-

eous, but nineteenth-century suburbs had contained some slums, such as Sultan

Street in Camberwell and parts of North Kensington, while other parts of

Kensington which contrasted with the area’s predominantly middle-class char-

acter were the Potteries and Jennings’ Buildings. Jennifer Davis has discussed the

social construction of the latter as a slum in terms very similar to the represen-

tation of ‘problem estates’ more recently. For example, many interwar council

Richard Dennis

42

D. J. Olsen, The Growth of Victorian London (London, ), pp. –, –; J. N. Tarn, Five

Per Cent Philanthropy (Cambridge, ), pp. –, –, –; Jackson, Semi-Detached London,

pp. –.

43

Jackson, Semi-Detached London, pp. –, –; M. Turner et al., Little Palaces:The Suburban

House in North London, – (London, ); J. H. Johnson, ‘The suburban expansion of

housing in London, –’, in J. T. Coppock and H. C. Prince, eds., Greater London

(London, ), pp. –.

44

Jackson, Semi-Detached London, pp. –; T. C. Barker and M. Robbins, A History of London

Transport, vol. : The Twentieth Century to (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

estates were castigated by owner-occupier neighbours as ‘Little Moscows’; at

Downham, in south-east London, a brick wall was built across one road to

prevent direct communication between homeowners and tenants. Although the

Potteries was the better known district outside Kensington (thanks to Dickens’

description of the area), locally Jennings’ Buildings had a worse reputation, partly

because of its Irishness and partly because of its location close to the commer-

cial heart of Kensington. Davis also shows how the buildings and their inhabi-

tants were an integral part of the Kensington economy, a symbiotic association

of wealth and poverty that was even more common in inner and central

London.

45

There were numerous reasons for the absence of residential segregation on a

large scale in central London. In the mid-nineteenth century, a labour-intensive

middle-class economy required constant access to tradesmen, building workers

such as plumbers, tilers and carpenters, and other skilled artisans, including

tailors, shoemakers, cabinetmakers and upholsterers, who could provide cloth-

ing and furniture to order. Many domestic servants ‘lived in’ or occupied mews

cottages immediately behind their employers’ homes. Through most of the West

End, aristocratic and ecclesiastical ground landlords continued to own the free-

hold of large estates and to grant building leases, subject to restrictive covenants

designed to maintain the high-status and exclusively residential character of their

holdings. But covenants proved difficult to enforce, particularly towards the end

of the nineteenth century, as ninety-nine-year leases expired on estates devel-

oped during the Georgian and Regency expansion of the West End. This was

especially problematic for estates close to the City or to increasingly commer-

cialised areas around Oxford and Regent Streets, as fashionable London moved

farther west – to Belgravia, Knightsbridge and Bayswater. The edges of great

estates, adjacent to commercial streets like Oxford Street or abutting smaller free-

hold estates that were less tightly controlled, were most vulnerable to subletting

and multi-occupancy. One strategy adopted by several ground landlords, includ-

ing the duke of Westminster, the marquis of Northampton and the duke of

Bedford, was to offer these marginal sites to model dwellings agencies to create

a kind of buffer zone or cordon sanitaire. Better a closely supervised block of

model dwellings than a disorderly slum. The Society for Improving the

Condition of the Labouring Classes developed its ‘Model Homes for Families’

() in Streatham Street on land owned by the duke of Bedford between

Modern London

45

Dyos, Victorian Suburb, pp. –; H. J. Dyos and D. Reeder, ‘Slums and suburbs’, in H. J. Dyos

and M. Wolff, eds., The Victorian City, vol. (London, ), pp. –; D. Reeder, ‘A theatre

of suburbs’, in H. J. Dyos, ed., The Study of Urban History (London, ), pp. –; P.

Malcolmson, ‘Getting a living in the slums of Victorian Kensington’, LJ, (), –; J. Davis,

‘Jennings’ Buildings and the Royal Borough; the construction of the underclass in mid-Victorian

England’, in Feldman and Stedman Jones, eds., Metropolis, pp. –. On problem estates in inter-

war London, see G. Weightman and S. Humphries, The Making of Modern London –

(London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Bloomsbury and the St Giles rookery; and the duke of Westminster provided

sites for several different housing agencies between Oxford Street and Grosvenor

Square (the northern edge of Mayfair), and in Pimlico and Chelsea. In practice,

the residents of such dwellings, which were invariably oversubscribed, were an

elite working class of skilled artisans or regularly employed policemen, postmen

and railway workers, rather than the ‘poorest of the poor’, but they still con-

trasted in social status with their wealthy neighbours.

46

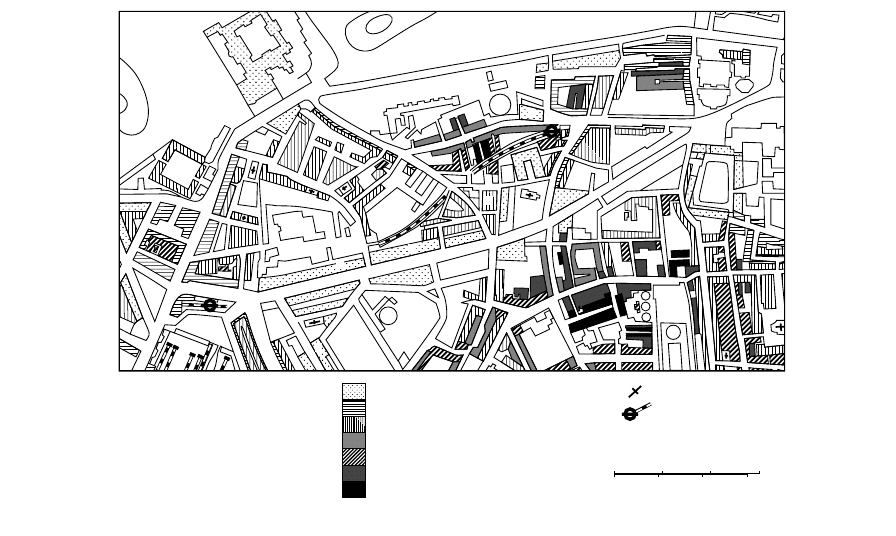

Nor was the overlap of different classes confined to ‘old’ areas of central

London. As with many new streets, one motive for Victoria Street – formally

opened in – was to get rid of a notorious slum – the Devil’s Acre. As else-

where, the slum was not eliminated but merely displaced. The Peabody Trust

erected one of its first philanthropic housing estates at Brewer’s Green (between

Victoria Street and St James Park) in ; and under the Cross Act () rem-

nants of Devil’s Acre on the other side of Victoria Street were replaced by further

Peabody estates. Victoria Street itself was lined by a mixture of office blocks

(known as ‘chambers’), shops (including the Army & Navy department store,

opened in ) and fashionable apartment buildings (so-called ‘French flats’).

47

Booth’s representation of streets like Victoria Street gives a false picture of social

homogeneity because his convention was to colour each street only one colour.

But even if Victoria Street was exclusively gold and Abbey Orchard Street all blue,

their residents could hardly have avoided contact with one another (Map .).

One consequence of this juxtaposition of slums, model dwellings and fash-

ionable apartments was the need for a more precise language of housing.

Apartments were invariably ‘Gardens’ or ‘Mansions’ while working-class dwell-

ings were ‘Buildings’. In Howards End, the Wilcox family took up residence

briefly in Wickham Mansions, whereas Leonard Bast, a modest city clerk patron-

ised by the Schlegel sisters, lived in ‘what is known to house-agents as a semi-

basement, and to other men as a cellar’ in Block B of a south London block of

flats.

48

More critical still was the language of the ‘slum’. The East End was treated

as a subject for exploration, ‘darkest England’ paralleling ‘darkest Africa’, or

apocalyptically, as in references to ‘the city of dreadful night’, ‘the inferno’ or

‘the people of the abyss’. The sub-human nature of slum dwellers was implied

by allusions to ‘rookeries’ and ‘dens’, and it was assumed that physical and moral

decay went hand-in-hand. The first stage to recovery involved a medical lan-

guage of incision and dissection to remove cancers and cut new streets. In the

process, the term ‘slum’ itself underwent a shift in meaning. Slums were no

longer individual properties in need of improvement or demolition. Under the

Richard Dennis

46

D. J. Olsen, Town Planning in London (New Haven, ; nd edn, London, ); Olsen, Growth,

pp. –; Dennis, ‘Victorian values’, –, –.

47

I. Watson, Westminster and Pimlico Past (London, ), pp. –, –, –; J. Tarn, ‘French

flats for the English in nineteenth-century London’, in A. Sutcliffe, ed., Multi-Storey Living

(London, ), pp. –.

48

Forster, Howards End, pp. –, –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cross Act () and its subsequent incorporation into Part I of the Housing of

the Working Classes Act (), the slum became an area for clearance, large

enough to allow redevelopment, but small enough to suggest that the housing

problem was simply a collection of problem areas, not a fault of the structure of

housing provision as a whole, let alone an inevitable consequence of the eco-

nomic system.

49

Initially, the slum problem was to be solved by individual and corporate phil-

anthropy – a first wave of agencies in the s, followed by the larger scale

Peabody Trust and Improved Industrial Dwellings Company in the early s,

and a third wave of five per cent companies, such as the East End Dwellings

Company and the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company (which catered

predominantly for Jewish immigrants), in the wake of Mearns’sensationalist tract

on The Bitter Cry of Outcast London and the ensuing Royal Commission on the

Housing of the Working Classes (–).

50

They acquired their first sites pri-

vately, often from other institutional landlords or aristocratic beneficence, but

the Cross Act provided a new means of acquiring sites cheaply in an otherwise

impossibly expensive central London land market. Indirectly, therefore,

working-class housing was subsidised out of the rates from as early as the s,

since the Metropolitan Board of Works, acting as the agency of slum clearance,

acquired property at market value, but resold the cleared sites to model dwell-

ings agencies for a fraction of the purchase price. Liberals argued that this was

not a subsidy, but rather a shrewd long-term investment which would more than

repay the initial outlay: rateable values and, therefore, revenue to municipal

authorities, would be increased, and the consequence of a healthier and happier

working class, well housed in a sanitary environment, would be a more law-

abiding and economically productive workforce, and a lower poor rate. The sec-

retary of one housing agency protested that his company was ‘a commercial

association, and in no wise a charitable institution’. It was the responsibility of

the latter, notably the Peabody Trust, to admit only ‘the very lowest order of

self-supporting labourers’, while the limited-dividend companies concentrated

on better-paid skilled workers, trusting to the effectiveness of ‘levelling up’ to

ensure some benefit to the poorest.

51

Unfortunately, ‘levelling up’was limited by the geography of the model dwell-

ings movement. After a few unhappy experiments in dockside areas of the East

End, where estates proved ‘hard to let’, the major housing agencies preferred to

Modern London

49

F. Driver, ‘Moral geographies: social science and the urban environment in mid-nineteenth

century England’, Transactions Institute of British Geographers, new series, (), –; S. M.

Gaskell, ‘Introduction’, in S. M. Gaskell, ed., Slums (Leicester, ), pp. –; J. A. Yelling, Slums

and Slum Clearance in Victorian London (London, ); H. J. Dyos, ‘The slums of Victorian

London’, Victorian Studies, (), –.

50

Tarn, Five Per Cent Philanthropy; A. S. Wohl, The Eternal Slum (London, ); J. White, Rothschild

Buildings (London, ).

51

Cited in Dennis, ‘Victorian values’, –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008