Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

period captured by the maps of and , those dates are useful bench-

marks for the era of urban industrialism. Fuelled by the railroads which linked

pithead to factory to port, this cycle of development encompasses the rapid

urbanisation of the s and s, the economic boom of the period to

, the ‘climacteric’ of the late nineteenth century, the regional shifts and

inflation of the early twentieth and the declines in production and employment

of the s and early s, and the growth of the later s and postwar

decade. By the s and early s shrinking employment in the export indus-

tries of the North testified to the erosion of urban prosperity in the heartland of

the Industrial Revolution. Then by the later s and s urban employment

shifted toward services while many jobs relocated outside the conurbations, tes-

tifying to a dynamic that went far beyond regional boundaries.

3

The urbanisation of the industrial period is not a placid story of progress and

easy growth. The leap from the Barchester of Anthony Trollope to the Bradford

of J. B. Priestley required more than a change of clothes and class. Contrasting

types of urbanity, of cultural identification, of work and play came along with the

growth and decline of industrial cities. Struggles for political and cultural control

came along with the railroad and the music hall, the board schools and the labour

exchange. Local identities contended with national ones and with the alluring

appeal of the capital. Cities created multiple ties as they offered multiple choices.

This chapter explores the changing shapes of British urban networks during

the era of high industrialism. On the one hand it is a story of economic growth

and decline; on the other it is a tale of adaptation and development, as many

manufacturing towns added a range of administrative and cultural functions,

which strengthened their regional importance. The combination of capitalist

investment strategies with the growth of state welfare service in a period of high

consumption has given cities multiple functions, and helped the centres of

British urbanism survive the economic shocks of the twentieth century.

(i)

Not only is the completely isolated city unviable, but it is a contradiction in terms.

As points of exchange for people, goods and information, linkage is the major

urban function. To say, as Brian Berry did, that ‘cities are systems within systems

of cities’, only makes explicit this assumption of flows and reciprocal influence.

Not only are cities interdependent, but significant changes in the attributes or

functioning of one member of a set triggers changes in its other members.

4

Lynn Hollen Lees

3

R. Floud and D. McCloskey, eds., The Economic History of Britain since , nd edn (Cambridge,

), vol.

I, p. , vol. II, p. ; D. Massey, Spatial Divisions of Labour (London, ), pp. –.

4

B. J. L. Berry, ‘Cities as systems within systems of cities’, Papers and Proceedings of the Regional Science

Association, (), –; A. Pred, Urban Growth and City-Systems in the United States,

– (Cambridge, Mass., ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Moreover, cities are differentiated; their systemic links are fostered by their need

to rely on other places for certain specialisations and functions. Geographers can

map the circulations of goods and people that link simpler to more complex set-

tlements, and doing so helps them to describe urban hierarchies, as well as to trace

the outlines of regions.

Marketing functions have had a central role in shaping urban systems and

intensifying differences. Because levels of demand for goods and services vary as

do the distances customers are willing to travel to obtain them, more settlements

house, for example, bakeries and filling stations than universities or hospitals.

The larger cities and towns will offer higher level goods and services, as well as

simpler ones, and will draw people from longer distances. This variance results

in a hierarchy of settlements in space: the capital city would offer a complete

range of goods and services, some of them to an entire region or country, while

a second order of central places would supply a more truncated list of goods and

services to a smaller area.

5

In the real world, of course, more than one urban

function shapes linkages – for example, communications, administration, culture

– and each set of locational decisions has longer-run consequences. Railroads

and road systems stream traffic and bring locational advantages as well as disad-

vantages. Administrative hierarchies generate investment, migration and

employment.

6

In practice, the largest cities became larger as they captured the

benefits of past investments in communications, governance, culture and com-

merce, which were generated in part because of a city’s initial size and regional

importance. As we shall see, technological change during the nineteenth century

tended to reinforce centrality and hierarchy, giving an advantage to the first-

comers in regional races for resources and influence, although many technolo-

gies of the twentieth century have proved compatible with the decentralisation

of recent decades.

But the first-comers also have an inherent disadvantage over the longer run.

Investment can bring obsolescence. As cycles of investment shifted among

regions, so too did the dynamism of technological innovation, expansion and

profitability. During the nineteenth century, successive waves of capital invest-

ment in the iron industry moved from South Wales and the West Midlands to

Scotland, then to the North-East, and finally to the East Midlands, driving a

dynamic of both industrial and urban growth, followed by relative decline.

7

Urban networks operate on multiple levels for multiple purposes. Even if

London politics and the London season outranked local varieties for people of

Urban networks

5

W. Christaller, Central Places in Southern Germany, trans. C. W. Baskin (Englewood Cliffs, N. J., ).

6

William Skinner has argued this point most persuasively using the case of China. See his ‘Regional

urbanization in nineteenth-century China’, in G. W. Skinner, ed., The City in Late-Imperial China

(Stanford, ).

7

R. A. Dodgshon and R. A. Butlin, eds., An Historical Geography of England and Wales, nd edn

(London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

national status and ambition, other places retained much independence. Not only

did county towns remain vital hubs of political and cultural life but so did regional

centres, such as Newcastle, Bristol and York. In fact, industrialisation in its early

phases might well have intensified regional identities and interactions.

8

The

dialect literature of Lancashire spread far and wide during the mid-nineteenth

century. The increase in functional linkages brought by new technologies of

transportation made local and regional exchanges easier, binding together local

producers and consumers, as well as their long-distance cousins. Far from erasing

differences in localities, industrial urbanism helped to solidify rich regional iden-

tities that linked together urban and rural worlds. Even if some urban linkages

ran to and from London, others were oriented to Birmingham, Manchester or

Cardiff. Still others remained resolutely local – to and from a market town or a

county capital, where the area’s bishop, its major chamber of commerce and trade

society were located.

In , the British central-place system of cities reflected several centuries of

locational decisions by producers, consumers, workers and the state, but in no

sense had a stable system been created.

9

In the first place, networks operated in

different ways for different people. Mail carriers and marquises, soldiers and ser-

vants, spinners and sailors quite literally moved along different roads. Certain

occupations bound a person within regional networks, and others did not.

Second, the structure of the capitalist economy produces regular change.

Capitalist production is technologically dynamic, which implies new invest-

ments of capital and labour not necessarily in the same spaces and forms.

Struggles for control of decision making, economic cycles of depression and

boom, as well as resistance to disinvestment and unemployment, intensify

instability.

10

Finance capital is footloose, as many firms and industrial towns have

discovered in recent decades, and its locus of possibilities regularly overleapt

national borders. Third, the growth of the state bureaucracy in the twentieth

century added a long-term pressure for centrality and congruence of service

functions that dampened regional differences.

11

Urban networks at any given

moment therefore have to be conceptualised in terms of the particular purpose

for which the network is being used and the social and economic status of the

Lynn Hollen Lees

18

J. Langton, ‘The Industrial Revolution and the regional geography of England’, Transactions of the

Institute of British Geographers, new series, (), –.

19

Hierarchy within a central-place system can be demonstrated in several ways, but is commonly

done in terms of town size. Larger populations are assumed to signal larger hinterlands, wider

influence and greater complexity of functions, an assumption encouraged by the fact that dem-

ographic data are much more readily available than information on marketing networks or the

distribution of functions and services. Although a radical reductionist method, ranking by pop-

ulation at least offers an approximation of a town’s relative local importance.

10

D. Harvey, ‘The geopolitics of capitalism’, in D. Gregory and J. Urry, eds., Social Relations and

Spatial Structures (Basingstoke, ), p. .

11

A. de Swaan, In Care of the State: Health Care, Education and Welfare in Europe and the USA in the

Modern Era (New York, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

people using the network. In their nation-wide campaign for universal male

suffrage, Chartists sometimes looked to a town electorate, sometimes to the arti-

sans or factory workers of a region, and sometimes to parliament for support.

They reached their audiences through local activities and neighbourhood

groups, through itinerant speakers, and through the Northern Star. Their cam-

paigns moved within town, region and nation in a tactical sequence, rather than

a necessary one. To understand urban interconnections requires a look at struc-

tures of possibility and then at patterns of utility.

(ii)

The British system of cities includes all the individual urban units within

England, Wales and Scotland, however they are defined. Using part of a politi-

cal unit to demarcate an urban system is of course highly artificial. What of the

rest of the United Kingdom or indeed the empire? Urban contacts do not cease

at a border; cities are part of ‘open systems’ that span geographic boundaries.

12

Wider connections will be explored later in this chapter, but for the moment

suspend disbelief and concentrate on the urban places of Great Britain alone.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the clarity of what constituted a ‘city’ had

long since disappeared. Legal, demographic and functional criteria jostled one

another in uneasy relation. Demarcation by charter, wall and market had given

way in Britain to a motley collection of administrative structures through which

parliament conferred urban status. There were municipal boroughs, local board

districts, utility companies and settlements with improvement commissions,

which produced, according to Adna Weber, ‘a chaos of boundaries and

officials’.

13

Over time, the problem intensified: annexations, enlargements of

areas served by utilities, the addition of new ministries and state functions piled

confusion upon confusion. Bowing to functionality, the census counted seaport,

watering-places, manufacturing, mining and hardware towns, as well as county

capitals and legal centres where the assizes met. To add further complexity, the

census labelled settlements with more than , inhabitants as urban, although

few such places had municipal governments or clear, unique geographic boun-

daries. In the designation of cities, English empiricism finally overrode the

results of ad hoc, decentralised systems of local government. By , statisticians

counted a total of towns with more than , citizens in England and

Wales, and more in Scotland with over , people.

14

Already a majority

of the British were urban dwellers, and over three-quarters lived in cities by

, if size of settlement is made the criterion of urbanity. By , only about

per cent of the population still lived in places which could be counted as

Urban networks

12

A. Pred, City Systems in Advanced Economies (New York, ), p. .

13

A. Weber, The Growth of Cities in the Nineteenth Century (Ithaca, ) p. .

14

Ibid., pp. , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

‘rural’, and many of them commuted into cities to work. In any case, automo-

biles, buses, radios and newspapers had long since eroded the cultural meaning

of place of residence. Britain today is effectively an urbanised society in which

towns set the pace and city dwellers imagine the countryside in forms that com-

plement their own modernity.

The British set of central places had ancient origins. It had developed in

several phases, starting first in the Iron Age. The Romans, of course, were active

founders of towns, but so too were the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes. Forts and

castles, bishoprics, markets and administrative centres attracted workers and mer-

chants, and some of them prospered. By the time of the Norman Conquest, the

British landmass was covered by an extensive set of settlements, only a few of

which had the formal trappings of a town. Then the late medieval consolidation

of political control which coincided with long-term population growth trig-

gered another period of town foundation from the eleventh through the thir-

teenth centuries, one which had an extensive impact in Wales and Scotland as

well as the English lowlands.

15

The next major phase of urban creation began in the eighteenth century along

with the rapid growth of industry and trade, and it added large numbers of spe-

cialised towns to the array. Ports, spas and manufacturing settlements attracted

new citizens at a rapid clip.

16

Mills set along the streams of Yorkshire and

Lancashire added housing, stores and churches, transforming themselves quickly

into towns. Rural mines needed workers, and entrepreneurs located factories

and furnaces nearby to benefit from relatively cheap coal and ore. Soon the

industrial growth of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries had sorted

and reordered regional urban networks, most intensely in South Wales, the

Scottish Lowlands, the West Midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire. People settled

near the sources of power in the early phases of British industrialisation. In

urban Britain comprised, therefore, an extensive array of settlements of many

sizes, functions, administrative structures and dates of origin, which in several

regions differed markedly from that of earlier centuries. History, technology,

geography and chance combined to produce this particular set of cities, which

remained relatively stable at the top ranks.

Describing this array of towns can be done in several ways: size, function and

regions are the most common methods. I will concentrate on size, since it

permits an easy charting of demographic changes and introduces the issue of rel-

ative scale In , the typical British urban dweller lived in a small town.

According to Brian Robson almost half of British towns had fewer than ,

Lynn Hollen Lees

15

See I. H. Adams, The Making of Urban Scotland (London, ); H. Carter, The Towns of Wales

(Cardiff, ).

16

H. Carter, ‘The development of urban centrality in England and Wales’, in D. Denecke and G.

Shaw, eds., Urban Historical Geography: Recent Progress in Britain and Germany (Cambridge, ),

p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

inhabitants, and most of the rest had under , in . Only a handful

exceeded ,.

17

At that date about per cent of the total English and Welsh

and per cent of the Scottish population lived in towns with fewer than ,

people (Table .). Of course, metropolitan London with more than . million

people dwarfed the rest, but Liverpool, Glasgow, Manchester and Birmingham

had become major cities. Between and , Glasgow had grown from

, to ,; Liverpool had exploded from , to , people.

Outside the capital, the largest British city in was Edinburgh, which had

only , inhabitants.

18

But by , a town of that size would not have made

it on to the list of the top twenty. By , Liverpool, Glasgow, Manchester and

Birmingham had more than , residents, and London swelled to more than

,,. Cities with more than , became commonplace, and decade by

decade, medium-sized places housed more and more of the English population.

By , few English and Welsh urbanites lived in towns of under , people,

and almost per cent had moved into the capital or cities that broke the half

million mark (see Table .).

The distribution of city sizes in Scotland is somewhat different. There small

towns have continued to be of greater importance. Indeed, over per cent of

the Scottish population lived in towns with fewer than , people in , and

relatively few settled in cities of , to , people. Only Glasgow became

a major metropolis. The period of industrial urbanisation produced in Scotland

a great many small towns and few places with six-digit populations (see Table .).

Between and , the numbers of settlements recognised as towns by

census takers and government clerks grew by leaps and bounds. (The

counted by Robson in had become by .) Each decade new small

towns appeared, as more and more settlements passed the urban size threshold.

At any given moment, of course, most towns were small, the vast majority

having fewer than , inhabitants. At the same time, the numbers of large

places rose at the expense of smaller ones, and urbanites slowly concentrated in

the bigger cities.

19

During the nineteenth century, once a town had established

Urban networks

17

B. T. Robson, Urban Growth (London, ), p. .

18

Data for British cities in the eighteenth century come from E. A. Wrigley, People, Cities, and Wealth

(Oxford, ), pp. –. For the period after , I use the urban populations compiled by

B. R. Mitchell, Abstract of British Historical Statistics (Cambridge, ), which are taken from

British censuses. For information on changing boundaries, see ibid., pp. –.

19

The relationship between urban size and growth has been much debated by geographers, since

statistical theory points in different directions. Brian Robson has investigated it in detail for nine-

teenth-century British cities. After tracing decennial growth rates of towns in all size classes, he

found that their variation contracted sharply as town size increased. Although small towns could

expand greatly or decline, larger places almost never shrank and tended to grow regularly at com-

parable rates. Indeed until town size and growth were positively correlated; bigger cities

grew more rapidly than small ones. After , however, average rates of growth became almost

uniform for towns of all sizes, although variance in growth was higher among the smaller settle-

ments. Robson, Urban Growth, pp. –, –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

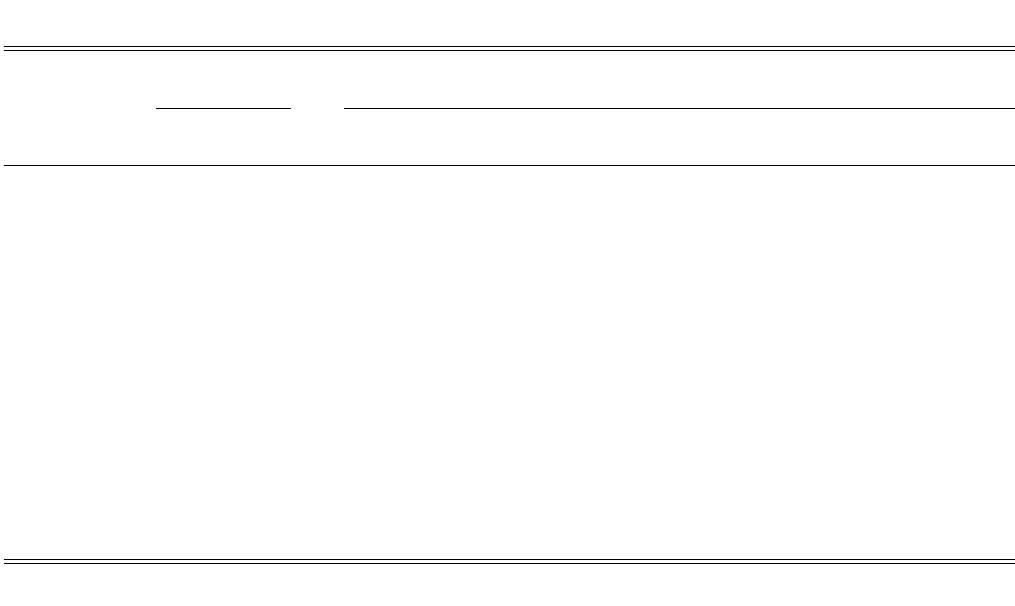

Table . Distribution of city sizes in Britain –

Population

(in millions) Percentage of total population in towns

,– ,– ,–

Total Urban All <, , , , >, London

Eng. & Wales . .. .. ...

Scotland . . .. . ..

Eng. & Wales ..... .. ..

Scotland . . .. . ...

Eng. & Wales ..... .. ..

Scotland . . ... ...

Eng. & Wales ... .. .. ..

Scotland . . ... ...

Eng. & Wales ... ......

Scotland . . ... ...

Source: R. Lawton and C. G. Pooley, Britain – (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

itself and moved out of the smallest size category, shrinkage in size was rare. The

process of city creation and expansion was sufficiently dynamic during the nine-

teenth century to embrace settlements of all types and sizes. But there was

enough variance in growth, particularly in the early decades of industrialisation,

to produce a shift in the higher order central places.

Industrialisation disturbed regional urban hierarchies and catapulted new

places to regional prominence. If a list of the largest fifteen British cities for

and are compared, enormous differences appear over time. Older county

towns such as Chester, Coventry and Exeter lost their relative position, while

newer manufacturing centres like Sheffield, Bradford and Dundee became major

cities. Meanwhile, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Birmingham gained

new prominence. By mid-century, the British urban hierarchy was dominated

by the capital, major ports and manufacturing centres. Thereafter, major changes

were few. Not only did the top five cities remain the same, but during the next

century only three towns – Nottingham, Stoke and Leicester – solidified a place

in the top fifteen. Portsmouth and Salford moved briefly into the top ranks

before moving down again in their relative ranking. The city systems of

advanced societies tend to be quite stable at the upper levels. Note the regional

implications of this growth pattern. Although all parts of the country experi-

enced rapid urbanisation, the largest new cities were located in the textile and

metalworking counties of the North and the Midlands. The early decades of the

century were their period of most rapid growth; only after did the South-

East develop an array of medium-sized towns outside London, when the shift-

ing dynamism of industrial sectors in south and north transformed migration and

investment patterns.

20

Industrial urbanisation not only added great size to great density of towns in

Britain, but major cities soon engulfed dozens of their small neighbours, which

vanished into new boundaries and statistical categories. In , Patrick Geddes

wrote of ‘this octopus of London, ...avast, irregular growth without previous

parallel in the world of life’, which devoured ‘resistlessly’hundreds of villages and

towns. Developers paved over historic divisions, turning subtle mixes of borough,

village and field into ‘a province covered with houses’. He marked out seven of

these city regions, or ‘conurbations’, which could be found from the Clyde to

South Wales. Except for London, each was centred on a coalfield, drawing its sus-

tenance from the power source of the factories, which would fuel continued

growth.

21

By the s, the conurbations of the Southeast and the industrial belt

housed around per cent of the English and Welsh population, a share that they

retained into the s (see Table .). During the industrial period, they formed

core areas of intense urbanisation, whose banks, industries and offices made up

the heartland of the British economy. Most of these conurbations continued to

Urban networks

20

Ibid., pp. , , .

21

P. Geddes, Cities in Evolution (London, ), pp. , , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

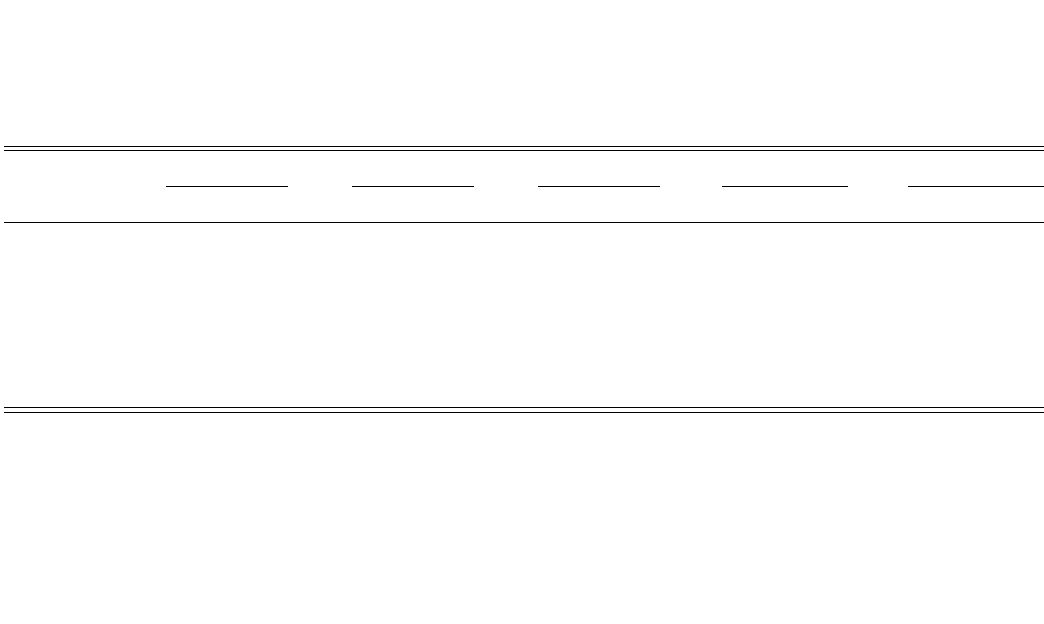

Table . Conurbations of England and Wales –

a

AB AB AB AB AB

Greater London , . , . , . , . , .

S.E. Lancashire , . , . , . , . , .

West Midlands , . , . , . , . , .

West Yorkshire , . , . , . , . , .

Merseyside , . , . , . , . , .

Tyneside , . , . , . , . , .

Total , ., ., ., ., .

Notes:

A=total population in thousands. B = percentage of total population.

a

Boundary change figures based on adjusted totals.

Source: P. Hall et al., The Containment of Urban England (London, ), vol. , p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

expand slowly until the s, when flight outside their borders outpaced migra-

tion and natural increase. But counter-urbanisation, when rural areas and small

towns are the most rapidly growing, has diminished their centrality in post-war

decades. The s marked the end of a long phase of urban development, in

which manufacturing fostered the expansion of particularly large cities. Since

that time, the comparative advantages of smaller places have shifted growth away

from the conurbations.

The transformation of town into city, city into metropolis and metropolis into

conurbation came about through the simple processes of addition and multipli-

cation: more people, more stores, more services, more land. The calculus of

industry produced an ever richer urban function. But investments, whether by

the state, by individuals or institutions, were not evenly distributed throughout

the urban hierarchy nor across the map of Great Britain for that matter, and their

inequality reinforced earlier locational decisions. By , an hour-glass shaped

area of intense urbanisation stretched from London and the south coast through

Lancashire (see Map .). In fact, David Harvey argues for a continuing shift of

surplus value within the urban hierarchy to central levels; urbanisation for him

is a process of concentration that stems from the nature of capitalism. Market

mechanisms combined with economies of scale, planned obsolescence and the

increased importance of fixed capital investment help to centralise surplus value

in the contemporary city.

22

Harvey’s argument works better for the period

before than more recent decades, however, when automobiles and elec-

tronic modes of communication encourage decentralisation of both residences

and production. The centralising impulses of capitalist industrialisation have

varied according to prevailing technologies and the shifting forms of business

organisation.

If the upper levels of urban networks of the early eighteenth century are com-

pared with those of the mid-twentieth, it is easy to see how both capitalism and

state formation contributed to greater centrality. Outside London in , the

five regional capitals described by Peter Clark and Paul Slack constituted the

most complex settlements in Britain.

23

Cathedrals, grammar schools, assembly

rooms, hospitals, jails and an array of churches distinguished them from tiny

market towns. Nevertheless, their stock of specialised institutions for administra-

tion, finance or welfare needs was small. Town halls, market squares and churches

served multiple purposes, and they represented high points of public investment.

Banks were non-existent, outside Edinburgh, Glasgow and London; firm, family

and finance operated symbiotically. Talented amateurs staffed local government,

and even the justices, sheriffs and lord lieutenants in charge of county-level

governance were drawn from local elites. Moreover, their economies were run

Urban networks

22

D. Harvey, Social Justice and the City (Oxford, ), pp. –, , .

23

P. Clark and P. Slack, English Towns in Transition, – (Oxford, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008