Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further Reading

Bauerlein, Mark. Negrophobia: Race Riot in Atlanta in 1906. San Francisc o: Encounter

Books, 2001.

Godshalk, David Fort. Veiled Visions: The 1906 A tlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of

American Race Relations. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Mixon, Gregory. The Atlanta Riot: Race, Class, and Violence in a New So uth C ity.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005.

White Supremacy

Racial stratification and white ra cism have fueled extralegal violence and ri ots

throughout the 19th and 20th c enturies. The 1906 Atlanta Riot provides one of

the more devastating and spectacular illustrations of the import of white

supremacy.

Over three days, the city that epitomized the promise and problems of the post-

Reconstructi on South was the scene of spontaneous and orchestrated violence,

rooted in long-standing racial tensions, emergent class conflicts, and the conse-

quences of urbanization. In particular, growing economic competition between

blacks and whites, demands f or civil rights, and a public panic over black crime

set the stage for the right.

Like so many other anti-black attacks in the post–Civil War South, the Atlanta

Riot of 1906 erupted a round issues of masculinity, honor, and hierarch y, most

commonlyexpressedaswhitemenprotectingwhitewomenfromallegedly

improper advance s by bl ack men. Newspapers reported four such assaults on

Saturday, September 22. A crowd of perhaps as many as 10,000 whites assembled

in Five Points. Initially, individual African American men were targeted by groups

of white Atlantans, who quickly turned their aggression against black-owned busi-

ness. As the violence escalated, it became more intense and increasingly random.

In response, armed groups of African Americans took to the street to protect their

community from further harm and defend their property from destruction.

Georgia governor Joseph M. Terrell deployed the state militia to quell the vio-

lence and regain control of the central business district, but it was only heavy rains

that dispersed the rioters at 2:00 a.m. on September 23. The presence of the militia

pushed the rioting to the suburbs on the south side of the city. Although meant to

restore law and o rder, over the next tw o days, the mil itia actually reinforced the

vigilantes’ efforts. Not only were there reports of violence and looting unchecked

by the militia, but in the end, it mobilized against African Americans organizing

686 Atlanta Race Riot (1906)

for self-protection, arresting as many as 250 of them in the community

of Brownsville.

In the end, the Atlanta Riot of 1906 resulted in the deaths of at least 25 and per-

haps as many as 70 African American men and two Euro-American men. An addi-

tional 70 African Americans were injured. Although largely forgotten in its

aftermathbymanywhiteAtlantans,theriot had profound consequences. Most

immediately, it devastated the African American commercial district. The events

of 1906 not only reflected white prejudice, but reinforced white supremacy, result-

ing in the passage of further restrictions on black suffrage. Finally, the riot of 1906

intensified tensions within the African American community, intensifying debates

about the best path toward equality, freedom, and dignity.

—C. Richard King

Further Reading

Bauerlein, Mark. Negrophobia: A R ace Riot in Atlanta, 19 06. San Francisco: Encounter

Books, 2001.

Mixon, Gregory. The Atlanta Riot: Race, Class, and Violence in a New South City. Gainesville:

Univ ersity Press of Florida, 2005.

Atlanta Race Riot (1906) 687

Springfield Race Riot (1908)

The Springfield, Illinois, race riot was notorious for the sudden violence in which

two prosperous black citizens were lynched, four white men were killed, and over

100 citizens were injured. Over the course of the two-day riot, dozens of black-

owned and Jewish-owned businesses were destroyed, along with many homes

occupied by black families. Thousands of black citizens fled the city, fearing for

their lives; some never returned. Significantly, very few rioters were held account-

able for the murder and mayhem.

On Friday, August 14, 1908, an angry mob of more than 5,000 assembled out-

side the Springfield j ail, eager to take justice into its own hands. One black pris-

oner, George Richardson, was accused of raping a white woman and another

black prisoner, Joe James, was accus ed of murdering a white man. When the

mob discovered it had been deceived and the prisoners had been moved, it sought

vengeance. Suspecting that Henry Loper’s car had played a role in moving the

black prison ers, the mob demolished Loper’s c ar and restaurant (Senechal 1990,

27–34, 95).

The Jewi sh-owned Fishman’s Pawn Shop was another early ta rget. The attack

appeared to have been planned in a dvance. The mob stole tools t hat they then

used to destroy the black residential neighborhoods known as the “Badlands”

(Anonymous 2008, 5). About one-quarter of the houses in that neighborhood were

owned by Isadore Kanner, a Russian Jewish immigrant. The police did not intervene

while the mob attacked the black neighborhood. The rioters attempted to protect

white families living in the Badlands neighborhood by having them pin white cloths

to their entrances. The riot took an uglier turn when rioters prevented firefighters

from putting out flames. Rioters also attacked black invalids (Senechal 1990, 35–

37). Scott Burton, a black barber, and William Donnegan, an 80-year-old retired

black shoemaker, were pulled from their homes and lynched. By 9:15 that evening,

the city had requested troops from the state of Illinois, and 500 militia were sent in.

By Saturday evening, 1,400 militia were stationed in Springfield, and they were

able to make headway against the mob. The police arrested suspected rioters, and

they prevented further att acks on black neighborhoods. Black families w ere per-

mitted to take shelter in the Springfield arsenal (Senechal 1990, 40).

Several times on Saturday evening, crowds formed, but in the major trouble

spots, they were dispersed by the militia. The crowds noted the pattern in the

689

way the militia were deployed, and they exploited the militia’s weaknesses by

causing trouble in areas where only small groups were on the loose. By Sunday

morning, the riot was over (Senechal 1990, 43–45).

On the first day of the riot, the rioters were seen as reformers who were ridding

the city of black people and of disreputable businesses such as gambling parlors,

saloons, and houses of prostitution. By the second day of the riot, perceptions had

changed. Upstanding citizens no longer stood among the crowds of onlookers,

offering tacit approval. The rioters wanted white-owned businesses to stop employ-

ing black workers. However, those who used black employees depended upon them

and did not want anyone dictating their employment practices. This segment of the

populace did not desire an “all-white” Springfield (Senechal 1990, 126). Also, by

this time, the nati onal press had picked up the story and residents were cons cious

of Springfield being cast in an unfavorable light (Senechal 1990, 48).

In another twist to the narrative of the Springfield riot, only black-owned busi-

nesses in the vice district were destroyed; all of the comparable white-owned busi-

nesses went untouched. The mob also destroyed black-owned businesses such as

barbershops, restaurants, shoemakers, an upholstery shop, and a bicycle shop

(Senechal 1990, 14). The black com munity had believed that assimilation would

come because of hard work and economic success. The attacks that took place

during the Springfield riot suggested that black citizens were targeted specifically

because of their economic success, a sobering repudiation of the American dream.

Many rioters were disadvantaged people who resented the achievements of the

black middle class. Even though the riot was over within two days, for several

weeks afterward, there were sneak attacks on black citizens. The police denied

that this was happening and provided no protection (Senechal 1990, 136).

Mabel Halle, the married white woman who accused a black man of raping her,

exonerated the man she originally accused, implicated another black man, then

finally conceded that she had had sexual relations with a white man who was

someone she knew. Her accusation had been one of the tinderboxes setting off

the riot, yet Springfield authorities never charged her with filing a false report.

She moved away within a few months (Senechal 1990, 158–159).

The grand jury brought 107 indictments against 80 people, including four police

officers who were accused of failing to stop the riot. There was only one conviction.

Rioters threatened people who were called t o testify, and white juries refused to

find rioters guilty (Crouthamel 1960, 176). The acquittal of Abraham Reimer

(sometimes spelled Raymer) was one of the most publicized. H e was an itinerant

Jewish peddler who participated in the riot and who was accused of lynching Wil-

liam Donnegan. Reimer’s case was unusual in that most people in the Jewish com-

munity of Springfield had been victims of the riot, not perpetrators. His case

received national coverage, and it sent the message that regardless of the evidence,

690 Springfield Race Riot (1908)

there would be little accountability for an incident that had exacted a heavy toll in

deaths, injuries, and property damage. Six years after the riot, the city of Spring-

field was still compensating victims for damages (Senechal 1990, 159, 181).

The lack of legal consequences for rioters fit in with local perceptions of what

had happened. Before the riot, Springfield had the reputation of being one of the

most corrupt Midwestern cities; this poor opinion only intensified afterward. In

the early hours of the riot, the mob wanted to exact revenge on two black prison-

ers. After the prisoners were moved, the mission shifte d to ridding Springfield of

disreputable businesses, under the guise of “reform” (Senechal 1990, 85). How-

ever, the unspoken mission was t o attack black-owned and Jewish-owned busi-

nesses, and to a ttack homes occupied by black families. Local law enforcement

was intimidated by the size of the crowd, and police did little to stop the rioters

until more forces arrived. By Saturday, when t he militia arrived in force and it

looked as though order would be restored, Springfield’s f our newspapers called

the rioters “bums and hoodlums” and “ riff raff” (Senech al 1990, 37, 47). Th is

change of opinion signaled more than semantics. Most Springfield residents

avoided thinking of the disturbance as a race riot (Senechal 1990, 169, 176). The

focus shifted from racism to issues of class. In their rush to put the race riot behind

them, Springfield residents looked for larger trends, such a s t he fallout from

urbanization and industrialization (Goldstein 2006, 62).

If influential citizens could think of the riot as stemming from hooliganism rather

than racism, they could avoid examining the role of racism in Springfield. No one

had to accept responsibility for the deaths of six citizens. Springfield citizens refo-

cused the blame on lax law enforcement and on corrupt city officials. Black victims

received no sympathy. In the wider arena of public opinion in the North, the riot and

its aftermath were harshly criticized. Spurred by the riot, black citizens worked with

social workers, activists, and philanthropists to hold an organizational meeting for

the NAACP in Springfield, on February 12, 1909 (Crouthamel 1960, 178–181).

—Merrill Evans

See also all entries under Stono Rebellion (1739); New York Slave Insurrection (1741);

Antebellum Suppressed Slave Revolts ( 1800s–1850s); Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831);

New Orleans Riot (1866); New Orleans Race Riot (1900); Atlanta Race Riot (1906); Hous-

ton Riot (1917); Red Summer (1919); Tulsa Race Riot (1921); Civil Rights Movement

(1953–1968); Watts Riot (1965); Detroit Riots (1967); Los Angeles Uprising (1992).

Further Reading

Anonymous. Springfield, Illinois, Race Riot of 1908. Springfield, IL: Springfield Conven-

tion and Visitors Bureau, 2008.

Springfield Race Riot (1908) 691

Crouthamel, James L. “The Springfield Riot of 1908.” Journal of Negro History 45, no. 3

(1960): 164–181.

Goldstein, Eric L. The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Senechal, Roberta. The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot: Springfield, I llinois, in 1908.

Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

692 Springfield Race Riot (1908)

Jewish Americans

For Jewish and black citizens, a history of contradictory relationships—both solid-

arity and distrust—marked the run-up to the 1908 riot in Springfield.

Like many other northern cities, Springfield experienced swift social and

economic change, straining connections among citizens. Some saw Springfield’s

leaders as corrupt, because they did not crack down on businesses such as brothels,

gambling parlors, and opium dens, facilitating a scofflaw atmosphe re (Senechal

1990, 134). Jewish and black citizens found themselves excluded from many busi-

ness and social opportunities. They felt they were treated with equal unfairness,

but it was hard for them to work together because of conflicting social currents.

Jewish immigrants to Springfield were quick to recognize anti-black attacks as

similar to the anti-Semitic pogroms that had caused them to flee Europe. However,

some Jewish citizens were afraid close associations with black people would drag

down their hard-won social status. Some Jews resolved this conflict by thinking of

the victims of pogroms as “innocent” Jews, while believing race riots had been

sparked by black criminality (Goldstein 2006, 62–67).

For Springfield Jews who had emigrated from cosmopolitan cities in Eastern

Europe, it seemed natural to do business with black customers. A dditionally, this

group of Jews tended to have higher occupational skills and did not perceive black

people as competing with them for jobs. These Jews often owned businesses such

as grocery stores, pawnshops, secondhand stores, and saloons. Most black writers

avoided criticizing Jews even in instances when they felt Jewish business owners

may have exploit ed the black community (Adams and Bracey 1999, 237–238 ).

Paradoxically, the black communi ty continued to view the economic success of

Jewish business owners as an example to be followed (Franklin 1998, 204). Thus,

the business relationships between blacks and Jews were less than solid. A

national recession in 1907 strained these already-fraying alliances.

The 1908 riot was a clear departure from business as usual in Springfield, in that

one of the rin glea der s was a R ussi an Jew, Abraha m Reimer (s ometi mes spelled

Raymer). Many Jews were ashamed of his racist activities, but an all-white jury

acquitted him of murder and of property crimes. Around the country, Jews sus-

pected Reimer had been a scapegoat (Senechal 1990, 97).

The riot defied any single inte rpreta tion. The mob destroyed 21 bla ck-owned

businesses and many Jewish businesses, to the extent that the element of anti-

Semitism was unmistakable. The attack on Fishman’s Pawn Shop appeared to have

been planned in advance, with rioters stealing weapons that were used to destroy

the black residential neighborhoods known as the “Badlands” (Anonymous 2008,

5). Many other Jewish businesses were looted (Senec hal 1990, 33). Isadore

693

Kanner, a Russian Jewish immigrant, owned one-quarter of the buildings that were

destroyed in the Badlands. During the mayhem, some Jewish citizens risked their

lives to protect their black neighbors (Senec hal 1990, 147). In t he aftermath of

the Springfield riot, Jews and blacks recogn ized that together, they had bee n tar-

geted for acts of terror. Together, they formed the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People within one year.

—Merrill Evans

Further Reading

Adams, Maurianne, and John Bracey, eds. Strangers and Neighbor s: Relations between

Blacks and Jews in the United States. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press,

1999.

Anonymous. Springfield, Illinois, Race Riot of 1908. Springfield, IL: Springfield Conven-

tion and Visitors Bureau, 2008.

Franklin, V. P., et al., eds. African Americans and Jews in the Twentieth Century: Studies in

Convergence and Conflict. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1998.

Goldstein, Eric L. The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Senechal, Roberta. The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot: Springfield, I llinois, in 1908.

Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People (NAACP)

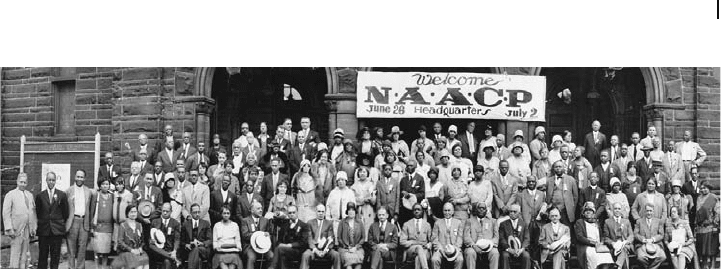

Riding a wave o f outrage over t he unpunished crimes of the Spring field riot of

1908, the NAACP sprang to lif e in 1909. It was a diverse coalition that included

abolitionists, black radicals, social justice progressives, and socialists (McPherson

1975, 388). The group formed on a national level and quickly started branches in

Chicago, Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C.

(Thornbrough 1961, 494). The founders planned for the NAACP to serve as a re-

source for black citizens, helping with public rela tions, social research, law, poli-

tics, and education (Rudwick 1957, 413).

When it was founded, the group was originally called the National Negro Com-

mittee but changed its name to the NAACP within the first year. One of the

NAACP’s first actions was to investigate the arrest of a black man in Asbury Park,

New Jersey, who was charged with murder. There was no evidence, and the

NAACP was able to secure his release (Ovington 1947, 108).

694 Springfield Race Riot (1908)

The NAACP drew its members from several organizations that had preceded it,

particularly the National Afro-American League, led by T. Thomas Fortune, editor

of the New York Age, who campaigned against mob law and lynching. The emi-

nent sociologist, scholar, and activist W. E. B. Du Bois joined the National Afro-

American League in 1905, re-e nergizing it a nd helping it laun ch the Niag ara

Movement, a group frustrated with the slow pace of social justice for black citi-

zens (Thornbrough 1961, 494–495, 509).

At the NAACP’s first conference in New York City, Du Bois presented scientific

evidence that blacks are not inferior to whites. He also showed the close relation-

ship of politics and economics. Without mentioning the name of Booker T.

Washington, a black leader who advocated a “gradualist” approach, Du Bois said

the de-emphasis on voting rights hurt rights for blacks overall (Rudwick 1957, 415).

At this confe rence, the NAACP adopted resolut ions similar to those of the

National Afro-American League, including strict enforcement of the U.S.

Constitution, particularly civil rights g uaranteed under the Fourteenth Amend-

ment. The gro up endorsed equal educat iona l opportunities, with equal expendi-

tures in public schools, and equal voting rights in accordance with the Fifteenth

Amendment (Thornbrough 1961, 511). The NAACP denounced the economic

and political repression of bl ack citizens. President William Howard Taft was

admonished to remove illegal restrictions on the hiring of black applicants for

federal positions. The group declined to denounce lynching but opposed violence

in general (Rudwick 1957, 417–418).

Du Bois’s role in the NAACP was one of applied sociology. He was editor of

the group’s journal, The Crisis, which advocated social justice for black citizens

in the United States and around the world (Deegan 2002, 63). The NAACP kept

a map with pins marking lynchings. It also tracked the destruction of black homes

(Ovington 1947, 112).

In its first decade, the NAACP’s achievements included building mass member-

ship, working against segregation in the federal civil service, working for legal

Springfield Race Riot (1908) 695

Participants of the 20th annual session of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, June 1929. (Library of Congress)