Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

cripple the company’s revenues had they joined the strike. The majority of scabs,

however, we re unemployed “white ” eastern railr oad workers, reflec ting that the

ARU’s strength was more on the Midwest and western rail lines.

General Managers Association

On June 28, only two days into the boycott, the General Managers Association

hired John M. Egan, formerly general manager on the Chicago and Great Western

Railroad, as full-time coordinator of antistrike activities. Denouncing the boycott

as “unjustifiable and unwarranted,” the GMA was deeply hostile to the ARU, fear-

ing, as the New York Times observed, “the permanent success of the one organiza-

tion throu gh which it is sought to unite all employees of railroads.” During the

cours e of the strike, the GMA spent at least $36,000 to oppose the Pullman boy-

cott. Thirteen large rail lines were assessed 5 percent of costs, with smaller lines

each contributing smaller portions.

A press bureau was established; 20 to 30 detectives were employed to provide

information on ARU strategy, strengths, and vulnerabilities, with a view to annihi-

lating the union. A coordinate d program notified railroad managers in eastern

cities to open agenci es to hire strikebreakers, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia,

Baltimore, Cleveland, New York, and Buffalo. About 2,500 workers were supplied

through this measure to various rail lines. Perhaps mo re deadly was the panel of

lawyers assembled under the direction of George R. Peck, chairman of the GMA’s

legal committee, to prepare strategy for judicial proceedings.

The primary line of attack was to position the ARU as interfering with U.S. mail

and with interstate commerce, to precipitate federal intervention, advising each

railroad company to institute proceedings through the office of the U.S. attorney

in various federal district courts. The U.S. attorney for Chicago obtained a writ

on July 3 prohibiting interference with mail trains, interstate trains, and interstate

comme rce not in transporta tion. The U.S. Strike Commission later recorded, but

could not confirm, charges that mail cars, normally included in freight trains, were

deliberately attached to passenger trains right behind Pullman cars, so that boycott

and strike action could be construed as interfering with the mails. General manag-

ers shut down passenger service and ceased accepting freight for shipment pre-

cisely to build public opposition to the strike. The ARU repeatedly offered that

striking workers would assemble and operate mail trains so long as Pullman cars

were not attached, but no railroad official responded to this offer.

Public Support

For the first month of the strike, Pullman w orkers received strong support in the

Chicago area, not only from union members a nd other workers, but also from

middle-class families and even business classes. Bertha Palmer, a leading socialite

646 Pullman Strike (1894)

and vice president of the Civic Federation of Chicago, which had sought to arbi-

trate the strike, observed that Pullman had been “grasping or oppressive in their

measures.” Palmer resented Pullman’s refusal to arbitrate. Chicago mayor John

P. Hopkins donated $1,50 0 to the Pullman relief fund. Th e Chicago Daily News

reported that many men h ired as strikebreake rs “have voluntarily given up their

positions to join the ranks of the strikers.” Other newspapers, while sympathetic

to the workers’ grievances, criticized the strike as ill considered. The Chicago

Record observed, “They struck at a time when the company was well able to stand

an interruption of its operations and precisely at the time when to strike is to share

bitterly with others in the industrial depression.”

Nationally, public opinion was molded by a virulently hostile press. In Chicago,

the ARU was violently opposed by the Chicago Tribune, Chica go Journal,

Chicago Herald,andChicago Evening Post. Photographs were not yet common

daily illustrations, but imaginative sketches of railroad cars and buildings in flames,

grim soldiers holding back rioting crowds at bayonet point, were picked up nation-

wide. Headlines such as “Mob in Control” and “Anarchy Is Rampant” were the pri-

mary information available outside of Illinois. The New York Times called anyone

wholeftworkinsympathywiththeARUcriminals,whileHarper’s Weekly

described the boycott and strike “blackmail on the largest scale.” Ministers in many

eastern states thundered from their pulpits against the “miscreants” of the ARU.

Federal Government Intervention

On July 2, John Egan candidly admitted that the railroads had been “fought to a

standstill” with, up to that time, a minimum of disorder. With railroad workers dis-

playing discipline, unity, and determination, Egan called for federal troops from

Fort Sheridan, Although no violence was in evidenc e, Egan called for the

government to “take this business in hand, restore law, suppress the riots , and

restore to the public the service which it is now depr ive of by conspirator s and

lawless men.”

Egan had goo d cause for opt imism. The U.S. att orney general was R ichard

Olney, who served as a director of three railroads after 35 years in private law

practice representing corporations. With Olney providing reports to President

Grover Cleveland, daily cabinet meetings established particularly close co-

ordination between Olney, Secretary of War Daniel S. Lamont, and Major General

John M. Schofield. The U.S. attorney in Chicago, Thomas E. Milchrist, conferred

regularly with the GMA, inviting them to provide names of anyone interfering

with the mails or interstate freight shipment. Although dispatches reported to

Washington on June 30, “No mails have accumulated at Chicago so far,” Milchrist

recommended that the U.S. marshal in Chicago be authorized to appoint 50 depu-

ties, which Olney immediately approved.

Pullman Strike (1894) 647

On June 30, Olney appointed Edwin Walker, general counsel for the Chicago,

Milw aukee and St. Paul Railroad, as sp ecial attorney for the federal government

at Chicago. Reports of delay in ma il shipment came in from R iverdale, Illinois;

Hammond, Indiana; Cairo, Illinois; Hope, Idaho; and San Francisco, California.

Some rioting was reported in Blue Island, a village outside of Chicago. On July 2,

Milchrist and Walker obtained a sweeping injunction from federal judges William

A. Woods and Peter S. Grosscup, listing 22 railroads as needing protection, charg-

ing the strikers with conspiracy against interstate trade in violation of the Sherman

Antitrust Ac t. Officials and members of t he ARU were forbidden to interfere in

any way with “mail trains, express trains or other trains, whether freight of passen-

ger, engaged in interstate commerce”; the application even specified that Pullman

Palace cars were indispensable to the successful operation of trains. Anyone

involved in the stated conspiracy was ordered to abstain from “ordering, directing,

aiding, assisting or abetting in any manner whatever” any individual committing

any act prohibited by the court’s order.

By July 4, the general managers declared, “So far as the railroads are concerned

with this fight, they a re out of it. It has now become a fight between the United

States Government and the American Railway Union.” However, between the

end of June and July 5, about two-thirds of 5,000 deputy marshals in the Chicago

area alone were provided, armed, and trained by the railroad companies. A captain

was de signated by any railroad desiring this service, and his name, together with

those he selected, was transmitted to the General Managers Association, which for-

warded the list to the federal marshal, who commissioned the men without exami-

nation. A Chicago police superintendent l ater testified that these deputies w ere

“more in the way than of any service,” while a reporter for the Chicago Herald

described them as “a very low, contemptible set of men.”

On July 3, with little sign of violence outside of Blue Island, but manifest evi-

dence that the recently deputized marshals were ineffective, Cleveland ordered

an entire army command from Fort Sheridan into Chicago. In doing so, he

bypassed Illinois governor John P. Altgeld, who had made no request for troops,

as well as the option of requesting assistance from the Illinois militia. Additional

reserves were moved in from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; and Fort Brady, Michigan;

from Madison Barracks, New York; Fort Riley, Kansas; and Fort Niobrara,

Nebraska. Troops were also ordered to Los Angeles, California ; Raton,

New Mexico; and Trinidad, Colorado.

After federal troops had occupied key points througho ut Chicago, lawless out-

breaks and rioting increased sharply. As tensions rose, crowds gathered on railroad

property and, by the evening of July 4, were overturning rail cars, then on the fol-

lowing day setting some on fire and blocking trains. By this time, the crowds

included an assortment of drifters, tramps, and y oung boys eager to have fun

648 Pullman Strike (1894)

throwing rocks at trains. On July 6, mobs destroyed about $340,000 worth of rail-

road property. Illinois Central rail cars were especially targeted, after one of its

railroad agents shot and killed two rioters.

Indictments End the Strike

Ultimately, a federal grand jury, more than the presence of federal troops, dis-

rupted the boycott and strike. Using a series of telegrams from Debs to various

ARU locals, none advocating violence and some cautioning against it, as evidence

of a conspiracy to stop trains unlawfully, Milchrist and Walker obtained indict-

ments on July 10 against all officers of the union. While they were being appre-

hended and detained, until bail was posted, the offices of the ARU were raided,

going far beyond the terms of a very limited search warrant. (Both Judge Grosscup

and Attorney General Olney repudiated the raid, ordering all private papers

returned.) Indictments were returned against hundreds of ARU members in many

other states, which, while later dismissed, spread fear and a sense that the strike

was lost. Refusing to turn a switch or fire up an engine was often treated as

grounds for arrest. On July 17, contempt of court proceedings also were initiated

against De bs, Howard, Keliher, and Rogers. Debs asserted that “Our men were

in a position that never would have been shak en under any circumstances i f we

had been permitte d to remain among them.” But because the union officers were

under arres t, “headquarters were demoralized and aba ndoned, and we cou ld not

answer any messages. The men went back to work, and the ranks were broken

up by the federal courts.”

Pullman posted a notice on July 18 that the shops would reopen, and all except

strike leaders might have the privilege of applying for work, provided they surren-

dered their ARU membership card and signed a pledge not to join a union. On

August 2, a convention of the ARU recognized that further struggle was hopeless,

and designated that since workers on each rail line had decided to strike, a vote on

each line should be taken to return to work.

—Charles Rosenberg

See also all entries under Molly Maguires (1870s); Great Railroa d S trikes (1877);

Haymarket Riot (1886); Seattle Riot (1886); Homestead Strike (1892–1893); Lattimer

Massacre (1897); Black Patch War (1909); Ludlow Massacre (1914); Boston Police Strike

(1919); Battle of Blair Mountain (1921); Bonus Army (19 32); Toledo Auto-Lite S trike

(1934); World Trade Organization Protests (1999).

Further Reading

Hirsch, Susan Eleanor. After the Strike: A Century of Labor Struggle at Pullman. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Pullman Strike (1894) 649

Lindsey, Al mont. The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great

Labor Upheaval. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1942.

Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: C itizen an d Socialist . Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1982.

Schneirov, Richard, Shelton Stromquist, and Nick Salvatore, eds. The Pullman Strike and

the Crisis of the 1890s: Essays on Labor and Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1999.

650 Pullman Strike (1894)

American Railway Union (ARU)

From 1893 to 1895, the American Railway Union offered a single industrial union

as an alternative to the many craft unions into which railroad employees were di-

vided, after failure of an attempt to federate the separate brotherhoods of firemen,

switchmen, brakemen, trainmen, conductors, and engineers into a Supreme Coun-

cil of the United Order of Railway Employees. Discussions in 1891 and 1892 cul-

minated in February 1893 with the first board meeting of the American Railway

Union in Chicago. Eugene V. Debs and F. W. Arnold had strong ties to the firemen,

George Howard to the conductors, W. S. Missemer and Sylvester Keliher t o the

carmen. The ARU represented a break with the distinct brotherhoods, which repre-

sented at most one-fourth of railway employees, but hoped to incorporate or work

cooperatively with t he existing organizations. Local lodges inquired about dual

members hip, but th e brotherhoods were generally hostile; Arnold and Missemer

left the ARU. Debs, the longtime national secretary-treasurer of the Brotherhood

of Locomotive Firemen, resigned, wrote the ARU’s initial Declaration of Princi-

ples, and emerged as president.

ARU was strongest in the west; the brotherhoods were more firmly established

in the older eastern railroads. Within a year, ARU reported 125 locals, with entire

locals of some brotherhoods switching thei r affiliation. The union’s short history

was defined by three major confrontations. The first concerned administration by

a federal court of the bankrupt Union Pacific Railroad, which in February 1894

slashed wages and enjoined employees from discussing the matter, much less

going on strike. After a month of bitter discussion in the u nion’s Railway Times,

speeches by Debs, and legal debate in court, another judge found for the union.

Early victory in a strike against James P. Hill’s Great Northern Railroad gave

the ARU confidence. Responding to three wage cuts in eight months, the union

decided that unless wages were restored, a strike would begin at noon on April 13,

1894. With ARU holding “ revival meetings” all along the Great Northern lines,

men of all crafts walked out, despite efforts by leadership of the engineers and fire-

men to cut their own deals with Hill. The St. Paul Chamber of Commerce, mostly

businessmen dependent on rail transport, offered an arbitration panel, which Debs

accepted, forcing Hill to do the same. The panel approved 97 and one-half percent

of the union’s wage demands.

Notably, Hill’s request for federal troops was not fulfilled, although U.S. mar-

shals were “ disposed to be governed by the railroad companies, attorneys and

U.S. Atty.” Success on the Great Northern line inspired 2,000 new members to join

each day for several weeks, swelling membership to 150,000, more than all the

brotherhoods combined. In the ARU’s next major battle, it faced a sweeping

651

federal injunction, and intervention of federal troops on July 3, 1894. The first

ARU national convention, meeting in Chicago on June 12, 1894, heard testimony

from striking employees of the Pullman Car Works, located in the company town

of Pullman, Illinois. Delegates voted a boycott of Pullman sleeping cars, which

quickly became a sympathy strike , when railroad management refused to detach

Pullman cars from trains. Intervention of federal troops, prosecution for violating

the injunction, and an extensive blacklist of ARU members and anyone who had

participated in the strike, broke the ARU, which held its last convention in 1897.

—Charles Rosenberg

Further Reading

Boyle, O. D. History of Railroad Strikes. Washington, D C: Brotherhood Publishing Co.,

1935.

Ginger, Ray. The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs. New York: Russell &

Russell, 1969, c. 1949.

Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: C itizen an d Socialist . Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1982.

Debs, Eugene V. (1855–1926)

Undoubtedly the most home-grown and widely respected socialist l eader in

American history, Eugene V. Debs grew up in Terre Haute, Indiana, where he

was born November 5, 1855. He left school in 1870, obtaining his first railroad

job, rising to fireman on the Vandalia Railroad, until he was laid off during a

depression in 1874. A founding member of Vigo Lodge #16, Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen, he later served as editor of the national BLF Magazine,

and grand secretary-treasurer. Debs was elected city clerk of Terre Haute in 1879

as a Democrat, and reelected in 1881. In 1884, he was elected to the state

assembly, and he married Katherine Metzel on June 9, 1885.

He resigned his BLF office in 1891, disappointed by the collapse of the United

Order of Railway Employees, intended to federate a variety of craft brotherhoods

on the railroads. A founder of the American Railway Union in 1893, Debs became

nationally known through his leadership of the ARU’s first, highly successful

strike, against the Great Northern Railro ad, and the subsequent Pullman Strike

and P ullman sleeping car boycott, which collapsed after the administration of

President Grover Cleveland intervened in support of the railway managers,

destroying the union. Debs was sentenced to serve six months in j ail by federal

judge William A. Woods, for violating an injunction against the boycott.

652 Pullman Strike (1894)

By March 1894, Debs renounced his Democratic Party affiliation, and declared

himself for the Peopl e’s Party (Populists). However, he declined to accept the

party’s 1896 nomination for president, which then went to the Democratic nomi-

nee, William Jennings Bryan. In January 1897, he publicly declared himself a

socialist, and was overwhelmingly chosen to run for pr esident on the Social

Democratic ticket in 1900. The newly formed Socialist Party of America (SPA),

organized in January 1901, ran Debs again in 1904, 1908, 1912—running a whis-

tle stop campaign from a train called the “Red Special”—and 1920 from his cell in

the Atlanta federal pe nitentiary, with campaign buttons urging a vote “For

President—Prisoner # 9653.” In his last race, admired and denounced because he

was imprisoned for opposing U.S. entry into World War I, Debs won nearly a

million votes.

Both a unifier and a maverick for the fractious socialist party, Debs opp osed

violence a nd sabotage, advocated legal means to bring about socialist victory,

but aggravated his more conservative comrades, such as Morr is Hillquit and Mil-

waukee socialist congressman Victor Berger, by cofounding the Industrial

Pullman Strike (1894) 653

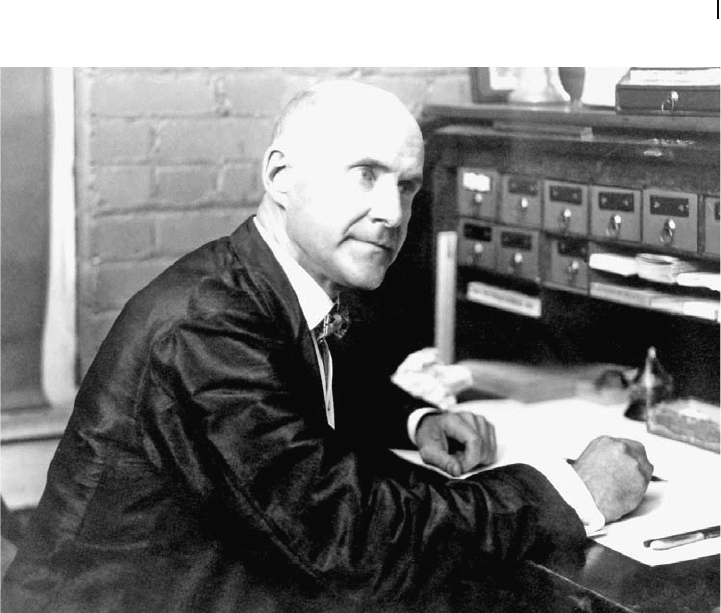

As leader of the Socialist Party of America, Eugene Debs ran for president of the United

States three times and was eventually imprisoned for his opposition to American

involvement in World War I. (Library of Congress)

Workers of the World in 1905, condemning “the malign spirit of race hatred” both

inside and outside the party, and standing by advocates of direct action such as

William D. “Big Bill” Haywood. Motivated by traditional American principles

of liberty, which he saw corrupted and degraded by industrial capitalism, Debs

appealed to many with his spirited defense of the individual dignity of every work-

ing man and woman.

Released from prison on December 23, 1921, his 10-year sentence commuted

by President Harding, Debs returned home to Terre Haute. Debs remained in the

SPA after the party’s left wings split to form two or three communist parties in

1919, but refused to unequivocally endorse either the remaining SPA lea dership,

or the communists, alternately criticized or appealed to by both. He died on Octo-

ber 20, 1926, five days after suffering a massive heart attack.

—Charles Rosenberg

Further Reading

Ginger, Ray. The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs. New York: Russell

& Russell, 1969, c. 1949.

Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: C itizen an d Socialist . Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1982.

Pullman Palace Car Company

This company was incorporated by charter from the Illinois legislature

February 22, 1867, to manuf acture, sell, and operate railroad sleeping cars , and

to own real estate that might be necessary for that business. Sleeping cars had been

attached to trains in the United S tates since 1836, but compa ny founder George

Pullman had developed prototypes, between 1858 and 1864, of more comfortable,

luxurious cars, costing four times as much as earlier models, believing passengers

would be willing to pay increased charges for the greater comfort. Technical inno-

vations, such as the hinged upper berth, matched introduction of the hotel, parlor,

and dining cars. By the time he sought incorporation, Pullman had 48 cars, costing

up to $24,000 each. Buying control of many competitors, b y 1894 the P ullman

company ran its cars on 125,000 miles of railroad, three-fourths of the track in

the United States, as well as in Canada, Mexico, England, Scotland and Italy.

Beginning with a capitalization of $1 million in 1867, the company had capital

stock valued at $15.9 million in 1885, with $28 million in assets. By 1895, ca pi-

talization reached $36 million and assets $62 million.

654 Pullman Strike (1894)

Pullman Company not only manufactured, but owned and operated the cars

attached to passengers trains of various railroads. It hired and paid the conductors,

porters, cooks, and waiters, receiving all net revenue; in return for performing

maint enance and repair on the cars, it received a two-cent mileag e fee fr om rail-

roads for each passenger ticket. In 1893, Pullman built 314 new cars, owning

and operating 2,5 73. In the p rosperous year of 1891, 64 percent of employees in

Pullman shops built cars for outside purchasers. Eighteen percent maintained Pull-

man’s fleet, and another 18 percent built palace cars for company use. For a time

after the Panic of 1893, purchase orders fell, and only a small fraction of employ-

ees worked to fill them. In 1893, $9.2 million of the company’s $11.4 million rev-

enue came from operating palace cars. Representative of the social attitudes of

many Republicans following the Civil War, Pullman insisted on hiring only

Negroes as porters and waiters, “because they know how to serve.”

His paternalism carried over into supervision of Pullman’s exclusively “white”

manufacturing employees, in both labor policies and the constructing and

administration of the town of Pullman. In 1880, the company decided to concen-

trate most manufacturing into a single new facility outside of Chicago. (By

1890, it had repair facili ties in at least seven other locations). Purchasing 4,000

acres on the western shore of Lake Calumet, Pullman built a massive factory cov-

ering 15 a cres, with four brick buildings three stories high, and a complete new

town. Brick tenements predominated, 10 per block, each housing 12 to 48 families

in two- to four-room flats. One water faucet was provided for every five families,

and two families shared a toilet. Salaried company officials lived in spacious

nine-room cottages. George Pullman ha s left li ttle record of his motivation for

insisting on relatively well-built, sanitary housing, a library, theater, and beautiful

parks, rather than hastily assembled wooden tenements. Many of his board of

directors opposed the expenditure. Pullman himself appears to have thought that

better ho using, and wholesome recre ational opportunities, would limit labor dis-

putes, and give the corporation greater stability. He also expected at least a 6 per-

cent return on his investment. The experiment was a business venture, not

philanthropy.

—Charles Rosenberg

Further Reading

Hirsch, Susan Eleanor. After the Strike: A Century of Labor Struggle at Pullman. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Lindsey, Almont. The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiement and of a Great

Labor Upheaval. Chica go: University of Chicago Press, 1942.

Schneirov, Richard, Shelton Stromquist, and Nick Salvatore, eds. Th e Pullman Strike and

the Crisis of the 1890s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Pullman Strike (1894) 655