Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Men watch the coming of the armed deputies—the p aid assassi ns of the Master of

the Mill.

It is half-past two in the morning. A scout stationed at Lock No. 1, on the Monongahela

River, reports the arrival of two barges in charge of a river steamer. They contain armed

men.

Now up—filling the great star-bespeckled bowl—goes the long, sad wail of the steam

whistle at the electric light plant.

It is the voice of Labor shrieking to the wage-worker to rise and make haste, for

armed Capital is to take possession of the workshop. Flash lights start from many points.

The night is over; horsemen dash through the streets of Homestead yelling: “To the

river; to the river—the Pinkertons are coming!”

They go to the river.

Half-dressed men and women, boys, girls, and children rush to the river. Each has a

weapon—some of guns, revolvers, knives, heavy irons, and sound sticks. Labor is in arms.

The river steamer Little Bill crowds on steam and speeds to the landing; the mob on

the bank races to intercept the armed men. It is a mad race in the morning light. Down

come f ences and other impedime nts. When the barges are within one h undred feet of

the landing, the advance guard of the mob is on the ground to contest the holding of it.

The mob warned off the armed men: “Don’t land or we’ll brain you.”

Out from the barge came the plank. Every Pinkerton man levelled his Winchester

rifle. A few of the bravest of them endeavored to land.

The sight of this infuriated the mob. They rushed forward and attempted to seize the

rifles.

One Hugh O’Donnell, a man of c haracter and heroic sou l, a mill hand, with three

others, hatless and coatless, w ith th eir backs to the Pinkertons, in fearful peril of their

lives, besought the mob to fall back: “In God’s name,” he cried, “my good fellows, keep

back; don’t press down and force them to do murder!”

A sharp report of a Winchester rifle from the bow of the boat answered him. In an

instant there was a sheet of flame —a rain of leaden hail. The crowd fell back a few feet,

then advanced, pouring deadly shots into the invading force.

The boat pulled out into the stream.

There were dead men on both sides.

And so ended the first battle of the morning.

When the armed hirelings of Andrew Carnegie poured their deadly volley in the

ranks of t he men who dared to demand one dollar more on their wages, there were

few guns among the people. At the crack of the Pinkertons first rifle men rushed to their

homes for firearms and prepared for battle in earnest. At half-past six a second attempt

at landing was repulsed.

Out on the stream lay the barges. The hot sun beat down upon them and the heat was

suffocating. Pinkerton’s men needed air. Rats require that. They started to cut air holes,

but the bullets of the mob on shore were too much for them. They decided that hot air

was better than bullets.

636 Homestead Strike (1892–1893)

An attempt was made to fire the barges by pouring burning oil on the river, but fortu-

nately this terrible ordeal was spared the Pinkertons.

Hugh O’Donnell, cool headed and brave, constantly endeavored to hold the men in

check. No one more than he wanted the rights of the men to triumph, but he did not

wish those rights to be steeped in human blood. He was talking to them when over the

barge a fluttering white flag told the story that the Pinkertons sought for terms.

The spokesman of the Pinkertons announced that they would surrender if assured of

protection from the mob.

They landed. Their arms were taken from them. With heads uncovered, to distinguish

them from the mi ll hands, they passed along between two rows of gu ards armed with

Winchesters. There were two hundred and fifty Pinkertons in line. And so t hose who

came to hold the Carnegie mills were led trembling away to the lock-up.

Silently, sa dly, and filled wi th fear, the disarme d Pinkertons , some bleeding, with

bedraggled clothing, haggard and pale-faced, walked between their captors. Some held

small bags with clothing. Alongside crowded the surging mass of hard-fisted men hurling

epithets at them. For some time they walked thus, hoping for the shelter of the jail.

Now woman comes to the front!

One snatched a bag, tore from it a white shirt and waved it. This action was almost a

signal to the brigade of women. They seized every bag and scattered the contents. With

yells and shouts the crowd cheered the women. There was a fine humor here; to scatter

the clothing of those who had come to scatter them.

Another woman threw sand into the eyes of a Pinkerton and cut hi m with a stone.

Then, in spite of the guards, the women cast stones and missiles at the unprotected Pin-

kertons. The guards hurried them over the unlevel ground to the jail.

There they were a sorr y lot. Cut, bruised, with eyes knocked out, with noses

smashed, the invading, conquered army escaped death in the jail. So ended an expedition

of two hundr ed and eighty men, armed with Winchesters, and supplied with provisions

for three months.

And behind the high board fence, with the barbed wires charged with electricity, rest

the mill hands waiting the developments of the future.

Source: Illustrated American, July 16, 1892.

Account of the Course of the Strike (1892)

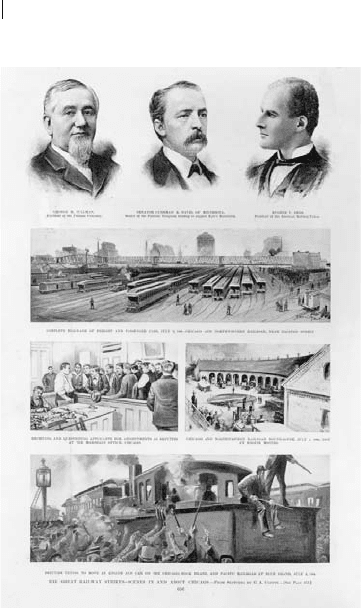

Reproduced here is a description of the Homestead Strike as it unfolded in July 1892 at the

Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Unlike the more disorganized, leaderless labor

uprisings of the previous decades, the Homestead Strike was well organized and led by the

Amalgamated Associa ted of Iron and Steel Workers, whi ch sought to improve wages and end

such practices as the use of yellow-dog contracts. The Carnegie Steel Company sought to break

the unio n by locking out workers and forcing a decrease in wages. The strik e ev entually failed,

and Carnegie Steel remained nonunionized for the next 40 years.

Homestead Strike (1892–1893) 637

“THE situ ation at Homestead has not improved,” wrote Sheriff McCleary to Gover-

nor Pattison, of Pennsylvania; and then he went on to say that while all was qui et, the

strikers were in control and had openly expressed to him t heir determination not to

allow the Carnegie works to be operated by any but themselves.

The poor sheriff had had a hard time of it. The governor blamed him for allowing the

PinkertonstogotoHomesteadtodohiswork.Whenhedidtrytoraiseapossehe

could only get a dozen citizens or so who had the pluck—or it may have been sympathy

with the strikers had something to do with it—to answer the call. Be this as it may, Sher-

iff McCleary threw himself upon the good nature of the governor, telling him that only a

large military force would enable him to control matters, and the governor gave orders

to Gen. George R. Snowden to place his entire division under arms and to take

8,500 men to maintain the Peace at Homestead.

This was no sooner said than done. By the morning of the 12th the troops were in the

town. So suddenly did they make their appearance, that before the strikers could realize

that they were actually there, the town was completely invested by the National Guard.

For a week the strikers had defied the law; mob rule had reigned supreme. There had

been peace since the battle with the Pinkertons, but it had been an armed and lawless

peace. Now all was changed. Gen. Snowden showed that he had gone to Homestead

with the full intention of main taining peace, and that he and his soldiers were not to be

trifled with.

Gen. Snowden appears to have carried out hi s plan of campaign wi th great m ilitary

skill. In the first orders, issued immediately after the governor had ordered out the

troops, Brinton, on the Monongahela River, and about a mile-and-a-half from Home-

stead, was announced as the rendezvous. It was his intention that the Second and Third

Brigades of the National Guard should gather there on July 11, go into camp for the night,

and march into Homestea d at daybreak the following morning. But the correspondents

got wind of his plan, and the details appeared in all the papers. There was a great chance

now of the rioters and their sympathizers collecting in great force at Brinton, and a pos-

sibility of their making an attack upon the soldiers befo re they reached Homest ead. To

prevent this, Gen. Snowde n alte red hi s pla ns an d noti fied hi s col onels t hat he had

selected Blair sville, a station on the Pennsylvania Rai lroad, about fifty-two miles east of

Pittsburgh for the rendezvous. The general intended this second order should leak out,

which it did, and duly appeared in the papers, but what his true intentions were he kept

to himself, not even taking his colonels into his confidence. When the soldiers reached

Brinton there were not less than ten thousand persons on the platform to meet them.

But at Brinton the conductor found orders to proceed to Wall, and at Wall to go on

somewhere, and so until the special reached Radebaugh, where there is a signal station.

The next morning the troops were in Homestead.

The rioters had got up a very pretty scheme, which they hoped would gain them the

sympathy of the public, and probably i t would have had they succeeded in carrying out

their project. They sent a delegation from the Amalgamated Association to Gen. Snow-

den at his headquarters. They decided to inform him that they had come to offer him

their assistance, but the general put on his most freezing manner when he told them he

638 Homestead Strike (1892–1893)

had no need of their services, he meant to preserve order himself. “I am here,” he said,

“by order of the governor to cooperate with thesheriffinthemaintenanceoforder

and the protection of the Carnegie Steel Company in the possession of its property.”

This was a terribl e snubbing for the delegation, for it had been intended to treat the

entry of the troops as a fete, and to let them marc h in to the strains of a brass band.

As Hugh O’Donnell, the labor leader, who was one of the delegation, said: “I never

met with such a chilling reception in my life. Gen. Snowden didn’t seem to have the slight-

est regard for what he said or thought.”

Meanwhile Congress had appointed a committee to go to Pittsburgh and investigate

the troubles and outbreak at Homestead. During the investigation Mr. H. C. Frick, chair-

man of the Carnegie Company, produced the letter he had written to Robert Pinkerton

on June 25, with regard to the hiring of 300 of his men to guard the Homestead mills.

“The only trouble we anticipate,” he wrote, “is that an attempt will be made to pre-

vent such of our men, with whom we will by th at time have made sa tisfactory arrange-

ments, from going to work, and possibly some demonstration of violence upon the

part of those whose places have been filled, or most likely by an element which usually

is attracted to such scenes for the purpose of stirring up trouble. We are not desirous

that the men you send shall be armed unless the occasion properly calls for such a mea-

sure later on, for the protection of our employee or property. We will wish those guards

to be placed upon our property, and there to remain, unless called into other service by

the civil authority to meet an emergency that is likely to arise.”

Hugh O’Donnell, the young leader of the strikers, made a brief statement, giving an

account of how the fight was brought about. Accordin g to him, about two o ’clock in

the morning an alarm reached the headquarters of the strikers that the Pinkertons were

descending upon Homestead. He went down to the ban k of the River Monongahela. A

big crowd of Hungarians, Slavs, women, and boys were on the banks, and were firing pis-

tols in the air. He advised the men not to fire and followed them as they moved up to the

point toward which the boat was heading. While he was addressing the crowd, urging

them not to use violence, a volley was fired from the barges and a bullet struck his

thumb. The firing lasted about five minutes. As to the way in which the surrender of

the Pinkertons was effected, O’Donnell told the following story:

I tied a handkerchief on the end of a rifle barrel and waved it over the pile of beams

behind which we lay . The men had promised me that in ca se the Pinkertons sur-

rendered they should not be shown any violence. When I waved my handkerchief

one of the guards came out on the barges and waved his hands. As soon as he

appeared one of our men jumped f rom beh ind his barricade and exposed himself

to the fire of the Pinkertons. I walked down the bank, and said to the man who

had come out on the barge, that I thought the thing had gone far en ough, and he

said he thought it had gone altogether too far. He then accepted my proposition

that his men should make an unconditional surrender, and should give up their

rifles. While the rifles were being unloaded, the crowd began to assemble on the

barges, and I must confess that during the march from the barges to the rink the

Homestead Strike (1892–1893) 639

Pinkerton men were shamefully abused by the crowd, but we took care of them

that night and saw that they got out of town safely.

Frick, the president of the company, is a determined man, and when he stated that he

would not give in to the strikers, everyone who knew anything of him believed he would

keep his word. But the strikers, too, were equally determined, and there was an inclina-

tion among them to rule Homestead by mob law. Anyone who was suspected of having

any connection with Carnegie’ s people was taken to the Rights of headquarters of

the strikers, there to be examined as to his mission, and personal rights were very little

regarded. Gen. Snowden threatened to arrest any one who dared to interfere with the

rights of citizens; but the strikers, who became more and more sullen each day

the troops were in their midst, had a wed the people, and nobody cared to act as

complainant in such a case.

Source: Illustrated American, July 23, 1892.

Two Examples of Yellow-Dog Contracts (1904 and 1917)

In an effort to inhibit the growth of unions, employers began using so-called yellow dog contracts,

which forced job seekers to swear not t o join a labor union as a condi tion of employment. The

term aros e from a popular saying—“y ellow-dog contracts” were so vile that no decent human

being would require even an old yellow dog to sign one. Although the term was not common until

after 1902, the practice was common in the 19th century. The 1932 Norris-LaGuardia Act and

the 1935 National Labor Relations Act abolished the practice, although many workers com-

plained that unwritten yellow-dog contracts persisted.

The first example below is a 1904 document required of Colorado miners seeking employ-

ment in the Cripple Creek region. It was usually accompanied by a housing lease agreement that

further reinforced the company’s antiunion position. The second contract reproduced here was

used by the Hitchman Coal and Coke Company. The Supreme Court , in Hitchman Coal and

Coke v. Mitchell, found the use of such contracts to be constitutional.

Mine No._______ Office No._______

APPLICATION FOR WORK

_______Mine.

_______ 190_.

Name, _______ _______.

Age, ____. Married? _____. Nationality, _____.

Residence, _____.

Occupation, _____.

640 Homestead Strike (1892–1893)

Where last employed? _____.

For how long? _____.

In what capacity? _____.

Did you quit voluntarily, or were you discharged? _____.

If discharged, for what reason? _____.

How much experience have you had as _____? _____.

Where employed before coming to Cripple Creek district? _____.

Are you a member of the Western Federation of Miners? _____.

Have you ever been a member of the Western Federation of Miners? _____.

If so, when did you sever your connection with same? _____.

Do you belong to any labor organization; and if so, what? _____.

References: _____ _____.

__________,

Applicant.

Remarks: _____

Source: U.S. Congress, A Report on Labor Disturbances in Colorado from 1880 to 1904,

Inclusive (1905), 278–80.

I am employed by and work for the Hitchman Coal & Coke Company with the express

understanding that I am not a member of the United Mine Workers of America, and will

not become so while an employee of the Hitchman Coal & Coke Company; that the

Hitchman Coal & Coke Company is run non-union and agrees wi th me that it will run

non-union while I am in its employ. If at any time I am employed by the Hitchman Coal &

Coke Company I want to become connected with the United Mine Workers

of America, or any affiliated organization, I agree to withdraw from the employment

of said company, and agree that while I am in the employ of that company I will not

make any efforts amongst its employees to bring about the unionizing of that mine

against the company’s wish. I have either read the above or heard the same read.

Source: Hitchman Coal and Coke Company v. Mitchell, 245 U.S. 229 (1917).

Homestead Strike (1892–1893) 641

Pullman Strike (1894)

In 1894, employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company joined the new American

Railway Union (ARU). Organizing began as early as January, motivated by pay

cuts instituted in 1893, and by longer-standing grievances. ARU’s reputation was

enhanced by a successful strike against the Great Northern Railway in April of

the same year. Organizing local s by craft, then federating them for united action,

ARU offered skilled and unskilled workers in all Pullman departments a way to

unite, much as it sought to unite all crafts throughout the railway ind ustry. There

were many locals within the Pullman works, covering upholstery, glass, electric,

paint, and freight departments, and Local 269, the “girls local,” representing

seamstresses who made and repaired carpets, drapes, linens, and seat coverings

for passenger cars.

Pullman Company had experienced strikes before, generally in a single produc-

tion department. Wood carvers struck in 1887, when traditional craft rules were

abridged by giving portions of their work to cabinet makers, and in 1888, when a

foreman was assigned by a superintendent, rather than chosen by the work crew.

The actions of individual foremen touched off short s trikes, as did introduction

of mass production methods in the lumberyard and in freight car building.

In May, Pullman workers presented their first set of grievances to company

management. Foremen laid off several members of the grievance committee on

May 10; the next day, 3,000 workers walked out of the car works, and the company

locked out the rest . It has never been established whether the layoffs were in

retaliation for the presentation of grievances; the company denied it, but employ-

ees at that point placed no reliance on the good faith of m anagement. In accor-

dance with tradition from previous conflicts, 300 strikers set up a perimeter

around the Pullman works to prevent violence and vandalism, vigilantly guarding

company property until this duty was taken over July 6 by federal troops.

Local Initiative and National Organization

ARU national leadership had opposed precipitous action. With three million

unemployed nationwide from the Panic of 1893, it appeared strategically prudent

to strengthen the organization before taking on a major battle. Pullman workers

had joined the union for immediate redress, and acted accordingly. Thomas

643

Heathcote, the Pullman Strike committee chairman, clarified, “We do n ot expect

the company to concede our demands. We do not know what the outcome will

be, and in fact we do not care much. We do know that we are working for less

wages than will maintain ourselves and families in the necessaries of life, and on

that one proposition we absolutely refuse to work any longer.” ARU president

Eugene V. Debs, after personally investigating workers’ grievances and observing

that costs of living remained at a pre-depression level while reduced wages were

well below subsist ence, told a meeting of strikers on May 16, “I believe a rich

plunderer like Pullman is a greater felon than a poor thief, and it has become no

small part of the duty of this organization to strip the mask of hypocrisy from

the pretended philanthropist and show him to the world as a n oppressor of labor

...The paternalism of Pullman is the same as the interest of a slave holder in his

human chattels.”

The strike had been underway for a month when the union’s first national con-

vention assembled in Chicago on June 12, 1894. After hearin g testimony fro m

Jennie Curtis, president of Local 269, other representatives from the town of Pull-

man, and Reverend William Carwardine, a local pastor sympathetic to the strike, a

committee of 12 delegates was chosen to suggest to the Pullman Company that

employee grievances be submitted to arbitration. The company’s second vice

644 Pullman Strike (1894)

Deputies endeavor to operate a train

engine during the great Pullman Strike of

1894. (Library of Congress)

president, Thomas Wickes, replied, “We have nothing to arbitrate,” and sub-

sequently referred to a committee of six representatives as “former employees”

who “stood in the same position as the man on the sidewalk.”

On June 22, a committee of convention delegates proposed the measure,

which made this strike famous: a boycott of Pullman palace cars. ARU members

on any and all railroads would refuse to attach Pullman cars to any passenger

train, until Pullman agreed to adjust or arbitrate his employees’ grievances. This

tactic had the potential to cut off the company’s largest and most reliable source

of revenue. It also would risk the very existence of the ARU on direct confronta-

tion with all railroad management in the United States, assembled into a power-

ful General Managers Association. The boycott and spre ading railroad strikes

also resulted in unanticipated direct federal intervention in support of railroad

management.

George Howard, ARU vice president, advised that closing Pullman’s shops at

St. Louis and Ludlow would cripple the corporation without the drastic measure

of a boycott. Debs deferred to a vote of the convention; delegates wired for instruc-

tions from their locals and were unanimously authorized to support a boycott.

After adopting the proposal, the convention sent three delegates to notify the Pull-

man Company. When Wickes responded that the company would neither deal with

union representatives nor submit any controversy to arbitration, th e boycott was

set to begin June 26.

The Conflict Begins

A predictable sequence of events rapidly escalated the co nflict. Switchm en were

on the front line: they would refuse to switch Pullman cars onto trains, and most

likely would be fired. The railroads’ General Managers Association (GMA) had

decided on June 26 to adopt that response, even if the employees were willi ng to

perform any other work assigned. (On June 29, it further decided to permanently

blacklist such workers from future employment with any railroad.) If replacement

workers, commonly referred to as “scabs,” took the vacant jobs, all union members

on that rail line ceased work. Within two days, 18,000 were on strike on seven rail-

roads operating out of Chicago. Much to Debs’s surprise, many more locals,

including affiliates of the more estab lished railroad b rotherhoods, spont aneou sly

informed strike headquarters at Uhlich Hall in Chicago that they had decided to

strike until the Pullman workers’ grievances were settled.

Pullman’s decision to hire only “white” workers in his manufacturing and repair

shops, and only “black” workers as porters on sleeping cars, served the company

well. The ARU, over Debs’s strenuous objections, had voted to allow only “white”

workers to join the union. Not only did this encourage “black” workers to accept

job s as replacements, it alienated the Pullman porters, who were in a position to

Pullman Strike (1894) 645