Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Indian Reservations

The concept of moving Native Americans to “reservations” started to try to pre-

vent wars between Native Americans and settlers. The system started in 1851

when the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act, which created res-

ervations in Oklahoma. The plans to move many of the Native Americans stalled

during the American Civil War, although several treaties such as those with the

Nez Perce

´

were signed. After the Civil War, the process of relocation started again

as the U.S. government decided to enforce some of the treaties.

The whole process ran into a number of problems. The first was that many of

the Native Americans did not want to relocate. It involved their leaving their hunt-

ing grounds, and also the lands of their ancestors where members of their tribe

had been buried for generations. Furthermore, many of the treaties signed between

the federal authorities and the Native Americans had involved some payment

by the federal government, either in monetary terms or in goo ds; and in many

cases, the money or goods were not delivered. An investigation in 1868 found

widespread corruption in the federal Native American agencies, with money being

stolen or e mbezzled. The last prob lem with many of the reservations was that

sometimesafterthetribewasrelocated, it was found that some of the land was

“needed” for other purposes, especially fertile land wanted by settlers for estab-

lishing farms. This often saw furt her reloc ation, and more consequent problems.

There was also often tension with Christian missionaries, w ho controlled some

of the schools and interfered in the traditional way of life of Native Americans.

By the late 1870s, much of Presi dent Ulysses Grant’s policy to relocate Native

Americans in reservations had been largely discredited. Rather than “solving” the

“problem,” it instead had seen wars between Native Americans and federal soldiers.

As a result, President Rutherford B. Hayes started phasing out the policy in 1877,

and five years later, Christian groups that had tried to convert the Native Americans

had to end their encroachments into reservations. There were then moves to allow

individual Native Americans to own land within the reservations, but this led to

some selling their land to white settlers, and the reservations became even less via-

ble than they had been beforehand. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 trans-

formed the whole system by ensuring that land was owned by tribes, not individuals.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Confederation of American Indians. Indian Reservations: A State and Federal Handbook.

Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1986.

Frantz, Klaus. Indian Reservations in the United States: Territory, Sovereignty, and Socio-

economic Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

557

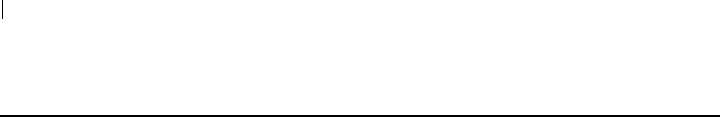

Joseph, Chief (1840–1904)

The chief of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce

´

, Chief Joseph’s father, Joseph the

Elder, was initially welcoming to white settlers in the region where the tribe lived,

the Wallowa Valley in northeast Oregon. However, the settlers gradually took

more and more land, and Joseph the Elder began to realize that unless something

was done, the Nez Perce

´

would lose all their land.

In 1863, when some Nez Perce

´

supported the signing of a treaty with the U.S.

government to vacate the Wallowa Valley, Joseph the Elder refu sed to agree to

this and represented the “anti-Treaty” faction of the tribe. As Chief Joseph

related, just before his death in 1871, Joseph the Elder told his son, “my body

is returning to my mother earth, and my spirit is going very soon to see the Great

Spirit Chief. When I am gone, think of your country. You are the chief of these

people. They look to you to guide them. Always remember that your father never

sold his country. You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty

selling your home. A few years more and white men will be all around you.

They have their eyes on this l and. My son, never forget my dying words. This

country holds your father’s body. N ever sell the bones of your father and your

mother.” Joseph added that, “I pressed my father’s hand and told him I would

558 Flight of the Nez Perce

´

(1877)

Chief Joseph (Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt),

as leader of the Nez Perce, orchestrated

one of the most brilliant military retreats

in history, earning him widespread

admiration among Indians and whites.

(Library of Congress)

protect his grave with my life. My father smiled and passed away to the

spirit-land.”

However, in 1877, the U.S. government was keen on enforcing the 1863 treaty,

and Chief Joseph was unc ertain about what to do. After General Oliver Otis

Howard gave him and the Nez Perce

´

some 30 days to vacate the Wallowa Valley,

Chief Joseph was about to agree in order to prevent war. But as the chiefs of the

Nez Perce

´

were deciding, they received news that four white settlers had been

killed, and they decided that their best policy was to flee, initially to the land of

the Crow pe ople, but b eing refused, Chief Joseph tried to lead his people to

Canada.

Chief Joseph was a proud man, but he recognized that he would have to use his

guile to evade pursuit by the U.S. Army. Although they were involved in skir-

mishes and battles, Joseph managed to lea d the Nez Perce

´

to within 40 miles of

the Canadian border. At the Bear Paw Mountains in Montana, on October 5,

1877, he and the Nez Perce

´

were cornered by the U.S. troops under General Nel-

son A. Miles, and Chief Joseph was forced to surrender. His people were dying

in the cold and from sickness and disease.

Some later historians argue that Chief Joseph did not lead the actual retreat,

which was done by more senior chiefs. However, so me of these had died in the

flight, and he was certainly in charge by the time of the surrender. By that time,

200 of the Nez Perce

´

(originally numbering 800) had died. In 1879, Chief Joseph

met with President Rutherford B. Hayes to press his case for his people to have

better land than that given to them in Kansas and then in the Indian Territory

(now Oklahoma), where many perished from disease. They were eventually

allowed to move to the C olville Indian Reservation. Chief Joseph was outspoken

about the injustice meted out to his people until his death in 1904, apparently from

a broken heart.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

French, Shannon E. The Code of the Warrior. Lanh am, M D: Rowman & Littlefield Pub-

lishers, 2003.

Howard, Helen Addison, assisted by Dan L. McGrath. War Chief Joseph. Lincoln: Univer-

sity of Nebraska Press, 1964.

Joseph, Chief. Chief Joseph’s Own Story. Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1981.

Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. The Nez Perce

´

and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press, 1965.

Flight of the Nez Perc e

´

(1877) 559

Relocation

The forc ed moving of the Native American people was known as “rel ocation.”

This saw them havin g to move from one place to an other—in the case of the

Nez Perce

´

, from Montana to smal ler landholdings in the same region, but obvi-

ously later, they w ould have to move to the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In

some ways, the actual moving itself wou ld not have many technical difficulties.

The Nez Perce

´

were a nomadic people, and their possessions, including their tee-

pees, were easy to move. H owever, they opposed relocation for other reasons.

They family lands, and their hunting lands could not be moved.

But it was not the hunting land that would have caused the most hurt. The Nez

Perce

´

had been living in the same region in Montana for centuries, and the ances-

tors of many of the Nez Perce

´

were buried in the land that was then having to be

abandoned when the tribe were relocated. One of the graves there was that of Chief

Joseph’s father, and Joseph had made a solemn promise to his father to look after

and protect this grave forever, and also was keen on maintain the lands where the

rest of his ancestors were buried. Therefore, it was these “intangibles” that would

present the most problems, a nd this was never understood much by the U.S.

government, who often felt that the Native Americans were being moved to what

were, in some cases, larger lands, or similar lands in other areas.

The main reasons for the relocations were to control the Native Americans and, in

the case of the Nez Perce

´

, to move them off some of the most fertile land, which

could then be used for cattle ranching or—as was argued at the time—for cultivation

on a far more intensive manner than that undertaken by the Nez Perce

´

or any other

Native American trib e. In a few cases, the move was away from land where gold

had been discovered. Either way, the land being given in return was always inferior,

and without their hunting grounds, the Native American tribes after relocation often

saw their societies fall apart. This had happened to so many Native Americans who

were forced to live a marginal existence, and the Nez Perce

´

would certainly have

been aware of this, which serves to explain their great reluctance at agreeing to leave.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Frantz, Klaus. Indian Reservations in the United States: Territory, Sovereignty, and Socio-

economic Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Nardo, Don. Relocation of the North American Indian . San Diego: KidHaven Press, 2002.

Williams, Jeanne. Trails of Tears: American Indians Driven from Their Lands. New York:

Putnam, 1972.

560 Flight of the Nez Perce

´

(1877)

Surrender Speech of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

´

,

October 5, 1877

The following is the speech of surrender that Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

´

is said to have made

following the Battle of Bear’s Paw on October 5, 1877. Although some historians doubt that

Chie f Joseph ever said these words, others find them consistent with the chief ’s reputation for

eloquence. Also, the words are said to have been taken down at the time by Lt. Wood, who

was present at the chief’s surrender. Nonetheless, Chief Joseph’s speech, and especially his clos-

ing words—“I will fight no more forever”—have become famous in American history.

Tell General Howard I know his Heart. What He told me before I have in my heart. I am

tired of fi ghting, Lo oking Glass is dead. Too-Hul-hul-sote is dead. T he old men are all

dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He wh o led on the young men is dead. It

is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people,

some of them have run away to the hills, and have no bl ankets, no food; no one knows

where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children

and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me,

my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight

no more forever.

Source: Mark H. Brown, The Flight of the Nez Perce

´

(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,

1967), 407.

Flight of the Nez Perc e

´

(1877) 561

Great Railroad Strikes (1877)

The Great Railroad Strikes of 1877 were the largest and most widespread job

actions by workers in the United States to that time. In many areas, workers from

other industries and crowds of unemployed people joined with the railroad strik-

ers, resulting in disruptions to business that are the closest the nation has ever

come to a general strike by all workers. The railroad strikes resulted from the

pay c uts and othe r changes in working co ndition s made by several o f the major

American railroads during the economic downturn in the aftermath of the Panic

of 1873. In October 1873, the failure of Jay Cooke’s investment banking firm

and the related bankruptcy of the Northern Pacific Railroad set off the Panic of

1873, the most severe economic recession the nation had yet experienced.

Between 1873 and 1875, 18,000 businesses failed, and unemployment may have

reached three million, perhaps as high as 25 percent of the workforce. The nation

did not fully recover from the Panic until at least 1878.

The railroads sought to respond to declining revenues by la ying off workers,

cutting wages, and running longer trains with fewer crewmen. Early in 1877, the

Pennsylvania Rai lroad, one of the largest eastern lines, laid off many employees,

cut wages 10 percent for their remaining employees, and announced plans to run

longer trains over portions of its system without hiring additional crews. In June,

the Pennsylvania announced another 10 percent wage cut, and at about the same

time, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad made similar cuts.

Railroad workers responded to these cuts by walking off the job and preventing

other workers from operating the trains. Historians disagree as to where the strikes

first began; it appears that work stoppages by railroaders on the Baltimore and Ohio

Railroad at Camden Junction, near Baltimore, Maryland, and at Martinsburg, West

Virginia, on July 16, 1877, occurred almost simultaneously. However, as historian

Philip Foner notes, the strikes “could have started anywhere along the 2,700 mi le

length of the B&O,” because all of the company’s workers had experienced severe

wage cuts, even greater than the general reductions that had been common through-

out the railroad industry. At Camden Junction, firemen walked off the job and were

soon joined by brakemen and a few engineers. In Martinsburg, workers took con-

trol of the railroad roundhouse and announced that no trains would be allowed to

leave the town. By the end of the first week, the strikes had spread to the major rail

centers in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio, and over the next several days, it

563

reached cities in the Northeast, the Midwest, and as far west as San Francisco. In

many localities, railroad workers not only refused to work, but kept other employ-

ees or newly hired strikebreakers from operating the trains.

In West Virginia, the governor sent the state militia to force the strikers back to

work, but the militia refused to use force against fellow working-class people. The

governor requested that federal troops be sent, and President Rutherford B. Hayes

sent in army forces. In Maryland, as many as 15,000 people may have clashed with

militia troops, and the governor requested federal assistance. Army troops and

U.S. Marines were sent to restore order in Baltimore. During the strike, federal

troops were sent to several major cities; the government argued that this use of

force was necessary to protect the passenger trains that often carried the U.S. mail.

Railroad workers were s ome of the first workers in major industri es in t he

United States to form craft or trade unions, in which workers were organized

according to their job specialty. Workers who practiced the same trade made

common cause in these craft unions, but often felt little in common with workers

in other crafts. Brakemen and switchmen, for example, believed that engineers

and firemen cared little about the issues they faced. In any case, these unions were

in their infancy in 1877, and the layoffs following the Panic of 1873 had caused a

sharp reduction in their membership; it is estimated th at craft unions represented

less than 1 percent of all workers in 1877. Many of the railroad workers involved

in the strikes belonged to no union, and even a mong the unio nized railroaders,

the job actions were usually “wildcat” strikes, which were not authorized by the

national leaders of the union.

Railroad workers were not the only people involved in the mass demonstrations

and violent clashes that accompanied the strikes in many cities. Often the crowds

were made up of workers from a variety of businesses as well as the unemployed,

and large numbers of women and children. While many of these demonstrators

had no direct tie to the railroad industry, they nevertheless saw the railroads as ene-

mies. Historian David O. Stowell has noted that in many cities, residents were pro-

testing the danger and inconvenience caused in their communities by railroad

tracks being laid in existing streets.

In the immediate aftermath of the strike, journalists and politicians sought

scapegoats to blame for the violence. Many suggested that socialist and commu-

nist influences brought on the strike. The Workingmen’s Party of the United States

(WPUS), which was the first Marxist workers’ party in the United States, was

often charged with instigating the strike. The WPUS had been founded in 1876,

and while it played a significant role in the strikes in several cities, it was simply

too small and had too little national influence to have had the kind of impact that

its critic s alleged. The party’s membe rship was only about 4,500 in 1877, and

was centered in the l argest industrial cities in the nation. The WPUS tr ied to

564 Great Railroad Strikes (1877)

encourage workers involved in the strikes and sought to provide some organization

and leadership wherever possible, but played no role in starting the strikes nation-

ally. The party’s headquarters were in Chicago, and while the party was active on

the local scene there, this meant that they were often preoccupied with local mat-

ters and unable to offer any national leadership. In Chicago, the WPUS called a

mass meeting in the heart of the city’s industrial district on July 23. An estimated

15,000 people attended that meeting, and that evening, railroad workers in the city

began to walk off the job. By the following evening, railroad traffic was at a stand-

still in Chicago, the majo r railroad hub in the nation. Over the next f ew days,

workers from the stockyards, the meatpacking plants, and many other industries

throughout the city joined in the strike. St. Louis, Missouri, along with nearby

towns on both the Missouri and Illinois sides of the Mississippi River, was where

the WPUS took the most active role in leading the strike. The party had about

1,000 members in the St. Louis area. An “Executive Committee” formed at the

party headquarters in St. Louis led the strike effort, and since local government

had virtually stopped functioning, some scholars have suggested this committee

took on the character of a worker’s “commune” and actually ran the city for a

few days. However, this may be somewhat of an exaggeration of the committee’s

impact. The strike in St. Louis reached far beyond the railroads, bringing work

to a halt at more than 60 factories and along the docks and levees where steamboat

freight was handled. Leaders of th e WPUS presided over several mass meeting s

and popular demonstrations. Finally, the leadership came to fear that these meet-

ings might get out of hand, and called for an end to such demonstrations. But the

mass meetings provided the WPUS leadership’s only real power, and without

them, nothing more was accomplished. Since local police could not stop the dem-

onstrations associated with the strike, 300 federal troops were sent from Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas, and finally restored order in St. Louis. By July 25, the strike

was largely over in St. Louis.

The Great Strikes of 1877 were the closest the United States has ever come to

experiencing a general shutdown by all worke rs. While the majority of workers

nationwide did not strike, there were widespread work stoppages in most parts of

the country—only New England and the South were largely untouched. The work-

ers who walked off t he job included f ar more than just the railroad employees.

Workers from a variety of industries, including unionized and nonunionized work-

ers, joined the railroaders in the strike. Besides striking workers, large numbers of

the unemployed, including women and children in many cases, joined in the mass

meetings, demonstrations, and violent encounters that accompanied the strike. The

unemployed were no doubt protesting the general economic conditions in the

country and the ir own lack of opportunity. Addi tionally, many nonrailroad work-

ers, and even many business owners, had long-standing grievances against the

Great Railroad Strikes (1877) 565