Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

faced 3 dead, 7 wounded, and more than 21 taken prisoner (R. R. Royal to Stephen

Austin, Austin Papers, III, 179).

By October 12, Stephe n F. Au stin, now commander i n chief, decided that the

forces mustering at Gonzales should capture San Antonio. They took the battle

to Co

´

s, rather than allow him to attack the settlements piecemeal. In dealing with

the rebel Texians, Co

´

s was shocked by their aggression. In his reply to Austin’s

request to vacate, he points that he, if anything, was too nice to the colonists:

“I might be accused of weakness, for having taken too much into consideration,

[for] the local interests of those new settlers, who wish to prosper by going beyond

the bounds set by nature he rself” (Martin Perfecto de Co

´

s to Stephen Austin,

Lamar 1968, vol. 5, 86) Co

´

s then implied to Austin that if his army does not desist,

a violent reprisal will follow (Martin Perfecto de Co

´

s to S tephen Austin, Lamar

1968, vol. 5, 87). The Texian numbers grew and included residents of San Antonio

like Pla

´

cido Benavides and around 30 othe r Bexaren

˜

os on October 15. On Octo-

ber 22, Juan Sequin joined the fight, notifying Austin tha t many others in San

Antonio were in support of the federalist cause (Hardin 1994, 28).

Rather than diminishing the will to fight, the unified Texians continued their

march. The first engagement occurred on October 28. Ninety rebels, led by James

Bowie, took on the approximately 400 Mexican soldiers at Mission Nuestra

Sen

˜

ora de la Purı

´

sima Concepcio

´

n. The Texians had one inarguable strength: their

weapons. The Kentucky long rifles of the Texians were superior in distance and

accuracy to the Mexican Brown Bess muskets. Utilizing this strength to the fullest,

the Mexican force was forced to retreat at the loss of 27 Mexican casualties. The

Texians meanwhile, had only one death.

With this victory, however, the Texians decided to lay siege to Bexar. This form

of wisdom over valor may have been smart, but this warfare was extremely stag-

nant to troops ready for action. Its effectiveness was displayed November 26 by

a skirmish known as the “Grass Fight.” A group of Texians attacked an incoming

mule train that was believed to hold gold. According to participant Henry Dance,

a force of 350 Mexican solders was engaged. The results of the battle were simple.

The Mexican army was “defeated and left the field 15 men left Dead [sic] on the

ground and many borne upon horses while our loss was one man wounded in the

shin [sic]” (He nry C. Dance to the Editors, Lamar 1968, vol. 5, 95). The Texians

were disappointed at only finding grass in the mule parcels. The fact that feed

for the animals had to be brought in displayed the siege’s effectiveness. The Tex-

ians also captured letters with the troubling news that reinforcements were on

the way.

Stephen Austin was called away to the consultation and William H. Wharton

was placed in charge. The Texians, however, soon grew anxious. On December 5,

Ben Milam was ready. The cry of “Who will go to San Antonio with old Ben

294 Texas Revolt (1835–1836)

Milam” was answered by more than 300 Texians. In grueling house-to-house

fighting, the Texians were able to slowly push the enemy back. Despite the fact

Milam “ fell Dead [,] Shot through the Brains with a Rifle while walking about

encouraging his men,” the advance continued ( Henry C. Dance to the Editors,

Lama r 1968, vol. 5, 97). By December 10, Co

´

s dispatched a soldier carrying the

flag of surrender. In the peace agreement, Co

´

s promised that he would not interfere

with the Texians and their battle for the Liberal Constitution of 1824.

With the battle for freedom being fought in the forefront, in the background, 48

delegates of the Consultation set about the work of explaining what the fight was

for, and how best prosperity could be maint ained. One faction, the War Party,

wanted an immediate declaration of independence. The other group, the Peace

Party, believed the best interests of Texas would lie in stayin g in Mexic o (Notes

Concerning the Consultation and Convention, Lamar 1968, vol. 2, 394–395). They

had been able to prosper and could prosper again. To do so, however, both a return

to the Liberal Constitution of 1824 and separate Mexican statehood would be

needed (J. Kerr, “Address against Independence,” Lamar 1968, vol. 1, 287–2 92).

Indeed, it was believed that the remaining Mexican federalists would rise to the

side of the Texians. On November 6, a vote w as called for. Only 15 of the dele-

gates wanted independence, whereas 33 voted for separate Mexican statehood

(“Notes Concerning the Consultation and Convention,” Lamar 1968, vol. 2,

395–396).

With reason for fighting decided, on November 7, 1835, a new provisional

government was formed. With it s birth, the all the unity that had bound the dele-

gates disappeared. Henry Smith of the War Party was chosen provisional governor

while members of the General Council were of the Peace Party. In the dying

moments of unity, Stephen Austin was dispatched to the United States for aid,

while Sam Houston was chosen to be commander in chief of the army.

Even the slightest semblance of unity disappeared over disagreement on a pro-

posed expedition to capture Matamoras. To those who gave support, it seemed like

the smart thing to do. By taking the war to Mexico, specifically Matamoras would

provide many benefits to Texas. Besides removing pressure on Texas, it would

provide a clarion call for Mexican federalists. Econ omically, Texas could use the

money from the customs collected at Matamoras; with the war distant, the

economy would face less damage. To the opposition, Texas could barely afford

the army it had, much less afford the waste on an expedition that may fail (James

W. Fannin to J. W. Robinson, Lamar 1968, vol. 1, 333). Overriding the governor’s

veto, Dr. James Grant was dispatched with 300 troops to take Matamoros.

(Colonel W. G. Cook, Lamar 1968, vol. 4, part I, 42). Governor Smith responded,

by disbanding the council. The council responded by removing the governor. Both

sides left vowing to hold another meeting at Washington-on-the-Brazos on

Texas Revolt (1835–1836) 295

March 1, 1836 (Notes Concerning the Consultation and Convention, Lamar 1968,

vol. 2, 395). During this time of need for solidarity and preparation, the

government was absent.

This lack of cohesion by the government was reflec ted in most of the military

matters. Units, hesitant to listen to an unknown Sam Houston, either disobeyed

or acted without orders. Even groups such as the Matamoros expedition, once dis-

patched soon turned piecemeal as rival groups went in pursuit of specific interests

(Reuben R. Brown, Account of His Part in the Texas Revolution, Lamar 1968,

vol. 5, 366–372). Some simply returned home. Although Colonel James C. Neill,

knowing he would have needed 1,000 more men to protect San Antonio, he

decided with his meager force to reinforce fortifications at the Alamo. As the

months passed into February, the urgency, and therefore speed diminished. Neill’s

requests for additional reinforcements also went unanswered (Winders 2004, 89).

Infighting and disunity caused a waste of the Texians’ most precious resource—

time; Santa Anna was beset by no such difficulty. When the capture of Bexar and

the humiliation of General Co

´

s became known, Santa Anna planned to crush the

rebel Texians. Utilizing the two main roads int o Texas, the El Camino R eal and

the Atascosito road, his troops could quickly eradicate the problems. The El

Camino Real wound through the c enter, while the Atascosito skirted the coast.

Through these two routes, the rebels would be crushed. As speed was paramount,

Santa Anna quickly amassed and dispatched his forces. He rushed to the El

Camino Real to capture San Antonio; meanwhile, General Jose

´

Urrea would take

500 infantry and cavalry up the Atascosito road to capture Goliad. By February 16,

1836, Santa Anna had crossed the Rio Grande.

The effects of this rushed march should h ave reaped h uge benefits. Indeed by

February 21, Santa Anna was on the outskirts of San Antonio de Bexar catching

the Texian rebels by surprise. The unseasonable weather, however, prevented the

crossing of a flooded steam. He had to wait two days for the waters to subside. This

allowed his presence to be known, and the al arm to be raised, while the garrison

prepared for battle.

As the rebels and their families rushed to sanctuary at their garrison at the

Alamo, the Mexican army prepared itself for a siege. Both sides were confident

of victory. The rebels, numbering a little more than 200, were confident of

reinforcement. The Mexican army, numbering around 2,000, believed a siege

would starve the rebels into submission while artillery pummeled the defenses.

By February 24, the siege began. Although the Texian rifles prevented the enemy

from getting wit hin 200 yard s of the fort, Travis began to use what he fe lt was

his most powerful weapon—a pen. Risking their lives, courier s rushed from the

defenses carrying dispatches. At first, the letters were full of confidence and brav-

ado. For example, in his letter of February 24, Travis, still sure of reinforcement,

296 Texas Revolt (1835–1836)

proudly boasts of how the enemy’s cannonade killed none, and his defiance to

demands of surrender (Wallace et al. 2002, 96). Travis pled to both the

government, which had not even officially met yet, as well as the comman der at

Goliad to send a relief column. As time passed, only 32 men from Gonzales fought

their way in to reinforce the garrison.

By the 10th day of the siege, its effectiveness was evident. As Travis found his

letters unanswered, his pen became sardonic. In his letter of March 3, Travis, pro-

phetically exclaimed he would “fight the enemy on its terms and his bones would

rebuke the lethargy of his countrymen.”

Travis would not have to wait long. On the evening of March 5, the Mexican

cannon stopped firing. The majority of the 189 Texians succumbed to exhaustion

and slept. The Mexican army of 1,800 soldiers advanced under the cover of dark-

ness. They would have caught the Texians unaware had not a nervous soldado

began to cry out “Viva Santa Anna.” Awakened, the Texian defenders quickly ral-

lied. Initial waves were repulsed; Santa Anna was eventually able to take the cita-

del. The clearing fog of war revealed 600 Mexican dead, compared to 189

defenders. The surviving family members, such as the Dickersons, were allowed

to leave so they could tell the colonials what might be in store for them. The news,

spread like wildfire across the Texas prairie, had a mixture of effects. Many fami-

lies immediately began evacuation in the “Runaway Scrape,” taking only provi-

sions they could carry. Some however, facing the seriousness of the calamity,

formed volunteer units to fight against the centralist threat.

Meanwhile, the new government found itself in a desperate situation. The 44 del-

egates met in a freezing Hall in Washington-on-the-Brazos. News from Stephen F.

Austin was not good, as many in v estors had supported a previous Mexican federalist

revolutionary, General Jose

´

Antonio Mexı

´

a, whose expedition met with disastrous

failure in November 1835. Mexı

´

a’s political connection with Texas soured many

responses to Austin’s pleas of support for a federalist revolution as he arrived in

the city in January 1836. Letters were sent home telling the Texians that if they

wanted financial support, independence should be declared. (Miller 2004, 105.) In

the litany of aggressions committed causing the separation, the document states that

although the colonists who “colonize[d] the wilderness” were rewarded by suffering

“military commandants, stationed among us, to exercise arbitrary acts of oppression

and tyranny,” and making “Piratical attacks upon our commerce, by commissioning

foreign desperadoes, and authorizing them to seize our vessels, and conve y the prop-

erty of our citizens to far distant parts for confiscation.”

Only for the cause of “self-preservation” were the Texians in favor of splitting

(Texas Declaration of Independence, in Wallace 2002, 98–99). So on March 2,

1836 , the collected delegates approved the declaration and Texas was to be free,

although those who died at the Alamo would never know.

Texas Revolt (1835–1836) 297

While Santa Anna was busy engaging the garrison on the El Camino Real, Gen-

eral Jose

´

Urrea was preparing to decimate resistance along the Atascosito road.

Arriving at Matamoros on January 31, Urreafoundthetownsafe.Thethreatof

Texian attack had apparently become victim of sloth. The Matamoros expedition

had stalled at San Patricio, close to the Nueces River, in search of more horses.

Urrea crossed the Rio Grande with a diminutive force of 320 infantry, 230 dra-

goons, and a small field gun and rushed to meet the enemy (Hardin 2004, 61). This

gamble would p ay huge dividends as by February 27, Urrea was able to catch a

smaller army both unaware and divided. At 3:00 a.m., Urrea pounced upon John-

son’s group of 60 men.

By dawn, fighting had ceased. Fort Lipantitla

´

n and 32 rebels were captured.

Twenty Texians dead with the loss of only one soldier and four wounded t o the

Mexican force. Indeed, only eight men, including Colonel Johnson were able to

escape. Questioning the citizenry, Urrea discovered that Grant would soon be

returning from his horse foray. Near the banks of Agua Dulce Creek, Urrea pre-

pared a n ambush. On March 2, the Texians unknowingly walked into the trap.

Dr. Grant and about 40 soldiers were slaughtered in the resulting battle.

Meanwhile, at Goliad, Commander James Walker Fannin found himself a victim

of Texas’s inaction. Many of the benefits that seemingly assisted his garrison, prox-

imity to Copano provided fresh recruits from the United States, provision of supply,

and the walls of his defense strong, seemingly made him strong. Appearances how-

ever, were deceiving. Demands were thrust upon him. The Matamoros expedition

had drawn off needed supply and soldiers. As events accelerated, desperate petitions

began to flow. Pleas for reinforcement, evacuation protection, and consolidation of

his units all demanded action. Meanwhile, the Mexican army was advancing. Fannin

dispatched Captain A mon B. King to he lp evacuate the fa milies at Refugio.

Supremely confident, King harassed the local ranchers. To his surprise, he ran into

the advance guard of Urrea’s army. Rather than leaving the field after the short battle,

King sent word for reinforcement (Samuel Bro wn, Battle of the Mission [Refugio],

Lamar 1 968, vol. 2, 8–10) Fannin agreed and dispatched William Ward and his

Georgia Battalion to the rescue. Upon arrival, on March 13, they found that King

and his men fortified in Refugio Mission. The group of 60 Mexican soldiers retreated

and used their time to harass local Tejanos. This waste played directly into Urrea’s

hand. On March 14, he arrived with his main forc e to find the rebel s once again

inside the mission. Although King and Ward defended the mission, they ran out of

gunpowder. At nightfall, they attempted escape. As their harassment of local ranch-

ers had won them few friends, King and his men were soon rounded up and taken

prisoner. Ward’s men were captured piecemeal and also taken prisoner. With the

countryside pacified, Urrea began to march on his objectiv e, Goliad (Samuel Brown,

Battle of the Mission [Refugio], Lamar 1968, vol. 2, 8–10).

298 Texas Revolt (1835–1836)

At Goliad, Fannin did nothing with the myria d of cal ls placed before him. On

February 26, he did try to take 320 of his men and four cannon to relieve the

Alamo however a wheel came off one of his wagons. As problems continued until

sunset and into the next day, it was decided to stay at the fort.

By March 13, Fannin finally received orders from his superior, General Samuel

Houston. Fannin was ordered to abandon Fort Defiance (Goliad) and retreat to

Victoria. Fannin was ready, but he wanted to wait on King and Ward’s return. So

he wasted four days only to discover they had been captured. On March 18, he pre-

pared for withdrawal, and on March 19, the troops began the move finally towards

Victoria. Fannin remained assured the Mexican army would not a ttack his more

than 400 Texians (Hardin 2004, 61).

Urrea’s army, which had been reinforced to more than 1,600 soldiers, was on the

outskirts of Goliad, at the same time that Fannin began his retreat. Fannin unknow-

ingly aided the enemy by stopping his troops after only an hour’s march for a rest

in the middle of an open field. Urrea discovered the vulnerable Te xians and quickly

used his cavalry to deprive them of cover. Although the Texians fought ferociously,

they soon ran out of water to swab their guns. By nightfall, the tally of 9 Texians

dead and 51 wounded was sm all compared to their predicament. With water and

food nonexistent and gunpowder running lo w, morale plummeted.

Sunrise intensified the grimness of the Texians situation. Overnight, the remain-

der of Urrea’s troops and artillery had arrived. Now facing a vastly superior foe,

the Texians sallied forth under a flag of truce (Joseph E. Field, “Fannin’s Surren-

der,” Lamar Papers, vol. 5, 120–121). Although only an unconditional surrender

would be g ranted, it was believed that they would be treated as prisoners of war.

They were marched back to Goliad, the prisoners were confident. So on March 27,

Palm Sunday, the prisoners were led out of the fort, believing they would be sent to

the United States. None questioned the fact that 83 of the prisoners, including a

14-year-old boy, were kept inside the fort. No resistance was offered. Santa Anna,

however, saw the Texians as nothing more than pirates, and as such, they could be

killed. Afte r being lined up in three s eparate groups, their guards received the

order to fire. Although 28 Texians were able to escape, 342 Texians fell dead in

what was known as the “Goliad Massacre” (S. T. Brown, “Account of his Escape

from Goliad,” Lamar Papers, vol. 2, 8–10).

News of the martyrs for freedom spread among a backdrop of chaos. On

March 11, Houston, who had been away negotiating peace with the Cherokee, had

returned to Gonzales to find that his army had been reduced to only 347 men.

Although believing he would be joined by Fannin’s men, the general kne w he could

not waste time. He began a series of retreats, and with each step, he incorporated

more volunteers and training. With Santa Anna close behind, many believed that

Houston was trying to get as close to the American border as possible to try to draw

Texas Revolt (1835–1836) 299

in American units. Then, on April 18, scout Erastus “Deaf” Smith captured a

Mexican courier whose dispatches showed Santa Anna had lightened his forces in

the race to catch the rebel government on the run. For the first time in more than a

month of retreat, Houston turned south. By the next day, knowing that Santa Anna

would be arriving at Buf falo Bayou, the Te xians took up camp in the woods. Hearing

the Texians were in the area, Santa Anna showed up at the bayou and made camp

only three-fourths of a mile away from the Texian camp.

On the afternoon of April 21, 1836, just 18 minutes would forever change

America. Although a min or cavalry skirmish had broken out the day before, all

had remained placid. The Mexican forces had received 540 reinforcements earlier

that afternoon bringing their numbers up to around 1,200 soldados, outnumbering

the 910 Texians. At noon, Houston held a council of war. With excitement build-

ing, between 3:00 and 4:00 in the afternoon, the Texian army began their advance.

A hi ll rising 15 feet had k ept the Texian movements from enemy view, and after

being at station for more than 33 hours, the Mexican soldiers were exhausted. At

4:30, the Texians crested the hill and, filled with rage and shouting “Remember

the Alamo—Remember La Bahı

´

a,” attacked, catching the enemy totally off guard.

Although the battle lasted only 18 minutes, the slaughter continued until the Tex-

ians became exhausted. Six hundred fifty Mexicans were killed, and more than

700 were taken pris oner, including Santa Anna. Only 9 Texians were killed, and

30 wounded. Houston took Santa Anna prisoner, where he was forced to recognize

the independence of Texas.

In its mad pursuit of self-governance for the sake of prosperity, Texas had won

independence. Texas would last almost 10 years as an independent nation, sur-

rounded by both danger and opportunity. The fact that Texas was a slave state sta-

tus slowed attempts at a nnexation. Mexico’s reluctance to recognize Texas’s

independence, and la ter its borders, also impeded talks. The eventual annexation

of Texas by the United States would lead to the Mexican-American War over con-

flict about the border. The lands acquired from that war, in turn, laid the ground-

work for the Civil War.

—Andrew Galloway

See also all entries under Bear Flag Revolt (1846).

Further Reading

“Alexander Thompson to William Thompson.” August 5, 1832. Texas State Historical

Association 7, no. 4 (April 1904): 326–328.

Almonte, Juan N. “Statistical Report on Texas, 1835.” Translated by C. E. Casta n

˜

dea.

Southwestern Historical Quarterly 28, no. 3 (January 1925): 177–222.

300 Texas Revolt (1835–1836)

Annual Report of the American Historical Association for 1919. The Aust in Papers.

Edited by Eugene Barker. Vol. 2. Part I, Vol. 3. Washington, DC: Government Printing

Office, 1924.

Barker, Eugene C. “Difficulties of a Mexican Revenue Officer in Texas.” Texas Historical

Association Quarterly 4, no. 3 (January 1901): 190–202.

Barker, Eugene C. Mexico and Texas 1821–1835. Dallas, TX: P. L. Turner Company,

1928.

Brinton, Crane. The Anatomy of Revolution. New York, Prentice-Hall, 1938. Revised ed.,

New York: Vintage Books, 1965.

Hardin, Stephen L. The Alamo 1836: S anta Anna’s Texas Campaign . Wes tport, CT:

Osprey Publishing, 2004.

Hardin, Stephen L. Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution. Austin: Uni-

versity of Texas Press, 1994.

Henson, Margaret Swett. Juan Davis Bradburn: A Reprisal of the Mexican Commander of

Anahuac. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1982.

Henson, Margaret Swett. Samuel May Williams: Ea rly Texas Entrepreneur. College Sta-

tion: Texas A&M University Press, 1976.

Hill, Jim Dan. The Texas Navy. Reprint ed. New York: Perpetua Book, 1962.

Lama r, Mirabeau Buonaparte. The Paper s of Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar. Vols. 1, 2, 4,

and 5. Edited by Gulick, et al. Austin, TX: Pemberton Press, 1968.

Lewis, Ca rroll A., Jr. “Fort Anahuac: The Birthplace of the Texas Revolution.” Texana 1

(Spring 1969): 1–11.

Miller, Edward L. New Orlean s and the Texas Revolution. College Station: Texas A&M

University Press, 2004.

McDonald, Archie P. William Barret Travis: A Biography. Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1995.

Rowe, Edna. “The Disturbances at Anahuac in 1832.” Texas State Historical Association

6, no. 4 (April 1903): 265–299.

Smithwick, Noah. The Evolution of a State or Recollections of Old Texas Days. Austin:

University of Texas Press, 1983.

Teran, Manuel de Mier, Texas by Teran: The Diary Kept by General Manuel de Mier y

Teran on His 1828 Exploratio n of Texas. Edited by Jack J acks on. Translated by John

Wheat. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.

Wallace , Ernest, David M. Vigness, and George B. Ward, eds. Documents of Texas His-

tory. Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2002.

Weber, David J. The Mexican Frontier 1821–184 6: The American Southwest Under

Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Winders, Richard Bruce. Sacrificed at the Alamo: Tragedy and Triumph in the Texas Rev-

olution. Abilene, TX: State House Press, 2004.

Texas Revolt (1835–1836) 301

Battle of the Alamo (1836)

After initial victories i n their war for independence, the Texians were supremely

confident. Indeed, 111 of the 189 defenders had routed the Mexican army from

San Antonio during the siege of Bexar. San Antonio was valuable real estate as it

lay on the major land route into Teja s, the camino real. The provisional

government remanded Commander Samuel Houston’s recommendation for the

Alamo’s destruction, as it was considered “the key to Texas.”

This seemed a monumental task. The garrison was underprovisioned, under-

manned and unprepared. Although six of the defenders were native-born Tejanos,

27 had been born in Europe, the remainder were born in the United States. Only 40

had lived in the Mexican province for more than two years. Their ages r anged

303

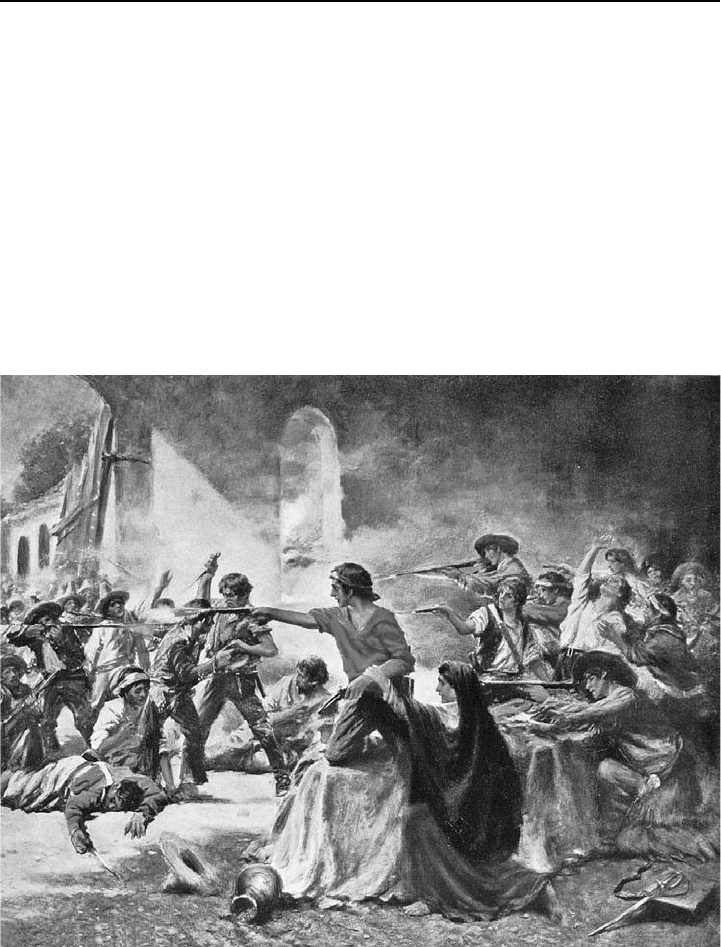

As depicted in a painting of the Battle of the Alamo by Percy Moran, Mexican soldiers under

Gen. Antonio Lo

pez de Santa Anna besiege Texans barricaded inside the Alamo during the

Texas Revolution. Numbering approximately 189 men, the Texans fought off the Mexicans,

who numbered around 3,000 to 4,000 troops, for 13 days until the Mexican Army finally

overran the Alamo on March 6, 1836. (Library of Congress)