Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Commonly referred to as “Prosser’s Gabri el,” he himself never took Prosser’s

name. Gabriel organized a predominantly urban insurrection, plann ing to con-

clude it by “drinking and dining with the merchants of the ci ty when our free-

dom has been agreed to.” The plan was to seize the state capital, Richmond,

secure the person of Governor James Monroe, then bargain for abolition of slav-

ery. At least two other leaders of the conspiracy were blacksmiths, like Gabriel;

most of those convicted in court for their participation were also skilled artisans.

Many were literate, and Gabriel was well acquainted with pu blished news and

political events in the United States and the Atlantic world. In rural areas, sup-

port was recruited not only among agric ultural laborers, but enslaved workers

in nearby coal mines, and the river boatmen who were essential to Virginia’s

transportation and trade. It is p robable that a number of people classified as

“white” were a t least sympatheti c to, i f not actively assisting the rebellion.

Whatever records that may have shed light on that question w ere forwarded to

Governor James Monroe, never produced in court, and never found again.

Gabriel ordered that Quakers, Methodists, and Frenchmen were not to be killed,

the first two because both churches had taken strong antislavery positions at the

time, the latter because revolutionary France had abolished slavery in all its col-

onies in 1794.

Slaves comprised 48 percent of Virginia’s population, as recorded in the 1800 cen-

sus, the highest proportion in the state’s history. With a substantial free African

American population, residents of African descent may have been a majority. In the

state capital itself, one-half of the population was African American, and one-fifth

of those were free. Vir ginia agriculture was in a difficult transition, with tobacco pro-

duction sharply declining and cotton not yet a large-scale cash crop. Farmland was

being planted in wheat and corn, which did not require intensive field labor, leaving

plantations with little work to assign to large numbers of slaves. A common practice

was to instruct slaves to hire their time—which meant, go find a job, and bring your

master the money when you get paid. It appears that the enslaved and free African

American communities held ski lled crafts and literacy in high regard. Organizers

for the army Gabriel planned to assemble made a point of displaying such skills to

potential recruits. Hiring out was also considered a desirable status, if only because

it permitted more freedom of movement, without obtaining a written pass for each

trip off an owner’s property. The ability to write, of course, meant the ability to forge

a pass for oneself, or for others. Planned for the night of August 30, 1800, the insur-

rection was delayed by torrential rains, which blocked roads into Richmond. On

either the day of or the day after the storm, at least four enslaved persons betrayed

the plan. Forty-four men were convicted of participation, 26 or 27 were hanged,

and the rest either pardoned or sold outside of the United States.

—Charles Rosenberg

264 Antebellum Suppressed Slave Revolts (1800s–1850s)

Further Reading

Egerton, Douglas. Gabriel’s Rebellion: The Virginia Slave Conspiracies of 1800 and

1802. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Sidbury, James. Plowshares into Swords: Race, Rebellion, and Identity in Gabriel’s

Virginia. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Vesey, Denmark (c. 1767–1822)

Denmark Vesey, leader of the largest and perhaps the most tightly organized slave

conspiracy in American history, was a free carpenter in Charleston, South Caro-

lina, when he began the work that has made his name so well known. The first

record of his existence was in 1781, when he was purchased, at the port of Char-

lotte Amalie on St. Thomas Island, by Captain Joseph Vesey, at the age of approx-

imately 14. Resold among a cargo of 390 enslaved persons in the French colony of

Saint Domingue (now Haiti), the young man either suffered, or contrived, fits of

epilepsy, so that on a return voyage, the purchaser demanded that Captain Vesey

buy him back as unfit for work. Vesey named him Telemaque, assigning him as a

cabin boy during subsequent voyages. At the end of 1782, Cap tain Vesey sailed

into Charles Town (later Charleston) , South Ca rolina, newly evacuated by a

British fleet, and Telemaque became a chandler’s man—helping to receive and

catalog imported merchandise in the captain’s business office. By 1800, his given

name had evolved to Denmark, when he won a lottery prize of $1,500. He pur-

chased his l iberty for $600, and opened his own carpentry shop, at some point

adopting the surname of his former owner. Greatly admired in both the free col-

ored community and the enslaved African community—which were quite separate

from each other—D enmark Vesey was also respected for the quality of his work

by customers designated as “white” who were the city’s elite.

Roughly seven years b efore 1822, when his plans were discovered, Vesey

decided to “see what I could do for my fellow creatures.” He recruited Peter Poyas,

Rolla Bennett, Ned Bennett, Monday Gell, and Gullah Jack, who helped him

assemble some 9,000 prepared to rise at his command. Vesey took careful notice

of the cultural identities within the enslaved communities of South Carolina at

the time, including a substantial number of Ibo, about 10 percent Muslim, as well

as the Gullah community, which had blended African and British cultures. Vesey

intended to kill every “white” person in Charles Town, at that time no more than

one-fifth of the population; load all enslaved persons onto ships in the harbor, with

every valuable they could take from the city; a nd sail to Haiti, the only nation in

the world forged in a successful uprising by enslaved people. Vesey scheduled

Antebellum Suppressed Slave Revolts (1800s–1850s) 265

Sunday, July 22, 1822, as the day to mobilize. Many Africans from surrounding

plantations would be in Charleston on a Sunday, and many of the city’s elite would

be escaping from the summer heat at northern resorts. Like most conspiracies, the

plan was b etrayed not once, but twice. The first informant knew only a little, so

that Poyas, Harth, and Bennett were able to boldly deny that anything was amiss.

Vesey moved up the date to strike to Sunday, June 16, but a second betrayal was

taken more seriously. A lower-level recruiter spoke to Peter Prioleau, w ho

promptly informed his owner, Colonel J. C. Prioleau. With militia mobilized to

secure the previously unguarded ar mory—a key point Vesey planned to seiz e—

and patrols in the street, there was no hope of success. The leadership was swiftly

arrested, 35 hanged, and 37 banished from the state.

—Charles Rosenberg

Further Reading

Egerton, Douglas R. He Shall Go Ou t Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey. Lanham, MD:

Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

Robertson, David. Denmark Vesey: The Buried Story of America’s Largest Slave Rebellion

and the Man Who Led It. New York: Vintage Books, 1999.

Description of Denmark Vesey (1822)

Denmark Vesey (c. 1767–1822) was an African American slave who was brought to Charleston,

South Carolina, from the Caribbean island of S t. Thomas in the early 1780s. In 1799, he pur-

chased his freedom from his master, Captain Joseph Vesey, and worked in Charleston as a car-

penter. Angered by the forced closing of an African Methodist Episcopal Church he had helped

found, Vesey began planning a slave insurrection that soon encompassed many slaves in Charles-

ton and along the Carolina coast. Betrayed to the authorities by two slaves who opposed his plan,

Vesey and many of his supporters were arrested and convicted of conspiracy. Thirty-five men,

including Vesey, were hanged. The following is a 19th-century description of Vesey.

As Denmark Vesey has occupied so large a place in the conspiracy, a brief notice of him

will, perhaps, be not devoid of interest. The following anecdote will show how near he

was to the chance of being distinguished in the bloody even ts of Sa n Domingo. During

the revolutionary war, Captain Vesey, now an old resident of this city, commanded a ship

that traded between St. Thomas and Ca pe Francais (San Domingo). He was engaged in

supplying the French of that Island with Slaves. In the year 1781, he took on board at

St. Thomas 390 slaves and sailed for the Cape; on the passage, he and his officers were

struck with the beauty, alertness and intelligence of a boy about 14 years of age, whom

they made a pet of, by taking him into the cabin, changing his apparel, and calling him by

way of distinction Telemaque, (which appellation has since, by gradual corruption, among

the negroes, been changed to Denmark, or sometimes Tebaak). On the arrival, however,

of th e ship at the Cape, Captain Vesey, having no u se for the boy, sold him among his

266 Antebellum Suppressed Slave Revolts (1800s–1850s)

other slaves, and returned to St. Thomas. On his next voyage to the Cape, he was sur-

prised to learn from his con signee that Telemaque would be returned on his hands, as

the planter, who had purchased him, represented him unsound, and subject to epileptic

fits. According to the custom of trade in that pl ace, the boy was placed in the hands of

the king’s physician, who decided that he was unsound, and Captain Vesey was compelled

to take him back, of which he had no occasion to repent, as Denmark pro ved, for

20 years, a most faithful slave. In 1800, Denmark drew a prize of $1500 in the East-Bay-

Street Lottery, with which he purchased his freedom from his master, at six hundred dol-

lars, much less than his real value. From that period to day of his apprehension he has

been working as a carpenter in this city, distinguished for great strength and activity.

Among his colour he was always looked up to with awe and respect. His temper was

impetuous and domineering in the extreme, qualifying him for the despotic rule, of which

he was ambitious. All his passions we re ungovernable and, savage; and to his numerous

wives and children, he displayed the ha ughty and capricious cruelty of Eastern Bashaw.

He had nearly effected his escape, after information had been lodged against him. For

three days the town was searched for him without success. As early as M onday, the

17th, he had concealed himself. It was not until the night of the 22d of June, during a per-

fect tempest, that he was found secreted in the house of one of his wives. It is to the

uncommon efforts and vigilance of Mr. Wesner, and Capt. Dove, of the City Guard,

(the latter of whom seized him) that public justice received its necessary tribute, in the

execution of this man. If the party had been one moment later, he would, in all probabil-

ity, have effected his escape the next day in some outward bound vessel.

Source: Joshua Coffin, An Account o f Some of the Pri ncipal S lave I nsur rections, and Others,

which Have Occurred, or Been Attempted, in the United States and Elsewhere, duri ng the Last

Two Centuries, with Various Remarks (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1860).

Antebellum Suppressed Slave Revolts (1800s–1850s) 267

Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831)

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, also known as the S outhampton County rebellion, began

on August 21, 1831, in Virginia, about 70 miles southeas t of Richmond. It is

remembered as one of a handful of antebellum slave revolts that profoundly

changed the attitudes of white American s toward slavery, and ma y, in fact, have

had the most significant lasting impact on the politics of slavery and on t he way

slavery is remembered as an institution in American cultural memo ry. The insur-

rection’s apparent mastermind, Nat Turner, is a man with multiple identities in

the historical record, his personality and motives endlessly shaped by the legions

of historians who have attempted to place the rebellion in the wider context of

American history and, for that matter, in the context of human social relationships

in the 19th and 20th centuries. Turner is remembered as a hero, a villain, a remorse-

less monster, a brave and bold v isionary, a crazed madman, and a liberator—all

depending on the persp ective of the person remembering Turner and his exploits.

He has been lionized as a hero of the aboli tionist movement and condemned as a

mass murderer of innocent women and children. His personality, and the insurrec-

tion he led, suffuses American popular culture, at once representing both the tragic

consequences of humans holding other humans in bondage while at the same time

symbolizing principled resistance t o inhuman suffering through cunning, ingen-

uity, and guile. While certain incontrovertible facts of the rebellion remain , little

is actually known of Nat Turner and the motives that caused him to undertake his

mission, leaving historians to piece toget her incomplete accounts of what Turner

did and why he did it.

Who Was Nat Turner?

Nat Turner was born on October 2, 1800, in Southampton County, Virginia. He

soon found himself identified as a person with unusual gifts of intelligence when,

at the age of three or four, he allegedly was overheard by his mother telling some

other children about events that had occurred before he was born. Since almost no

record exists either of Nat Turner’s personal life or events that occurred within it,

let alone any record written in his own hand, it is difficult to say if such stories

reflect the legend of the plot Turner eventually consummated as an adult, or are

269

accurate representations of things that happened in his life. Indeed, the predomi-

nant caricature of Nat Turner as an astutely intelligent and deeply religious slave

has served c ross-purposes for historians and cultural commentators since even

before Turner was ha nged for his role in the Southampton rebellion. On the one

hand, his intelligence was used in the immediate aftermath of the insurrection to

justify the impositi on of even harsher regulations on the education of slaves in

Virginia and across the South. On the other hand, Turner’s remarkable intelligence

is also often c ited as evidence of the enormous fissures in the proslavery world-

view, much of which was based on the idea that Africans were inherently inferior

to white people. What little historia ns do know about Turner and his lif e comes

largely from a conversation Turner had with a white lawyer named Thomas Ruffin

Gray while Turner was awaiting execution. This conversation was, of course,

270 Nat Turner ’s Rebellion (1831)

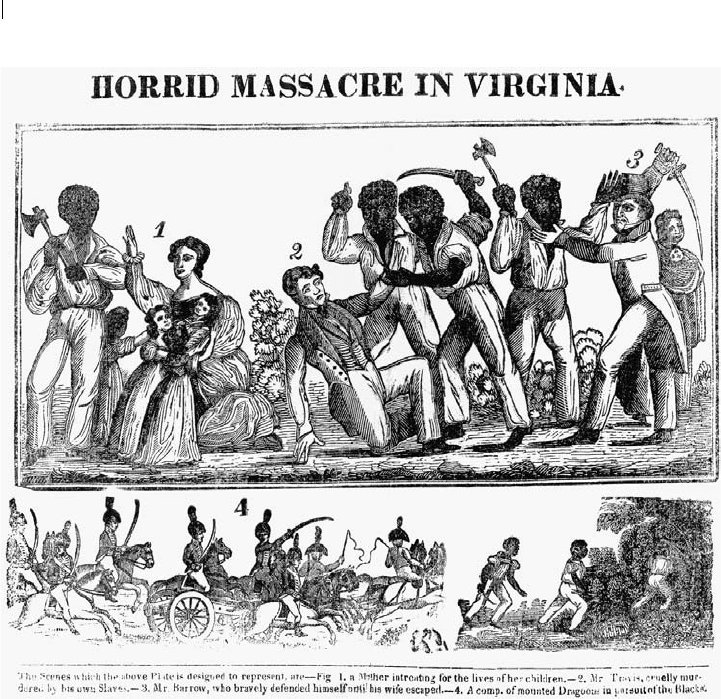

A newspaper cartoon depicts the violent slave uprising led by Nat Turner that began on

August 22, 1831, when Turner killed his master and his master's family. The revolt only

lasted about a week but Turner eluded capture until October of that year. He was later tried

and hanged for the crime. (Library of Congress)

recorded and recounted by Gray, who, for better or worse, filtered Turner’s words

to publish them in the newspaper.

Whatever Nat Turner’s experiences were as a boy, he was encouraged to

become a preacher by both his master and his grandmother, who noted in Turner

“uncommon intelli gence for a child” and, according to Gray’s report of Tur ner’s

confession, believed that his intelligence would result in him never being “of any

service to a nyone as a slave.” As a young man, Turner began to see visions. He

ran away from slavery in 1821, only to return—“to the astonishment of th e

Negroes on the plantation,” he later said—30 days later when he said he was told

in a vision to return to t he service of his “earthly master.” Turner also descri-

bed seeing, in the same vision, “white and black spirits engaged in battle” as

“blood flowed in the streams,” while a voice warned him: “Such is your luck, such

you are called to see; and let it come rough or smooth, you must surely bear it.”

In 1825, after Turner had been sold following the death of his previous owner, he

experienced another vision. This time, he said he saw “lights in the sky” that were

“the lights of the Saviour’s han ds” and said that he “wond ered greatly” about the

visions he saw “and prayed to be informed of a certainty of the meaning thereof.”

Later , while working in a cornfield, Turner claimed to hav e seen “drops of blood drip-

ping on the corn, as though it were de w from heav en.” Turner shared his strange expe-

rience with others, along with an interpretation of them. In his view, “the blood of

Christ had been shed on this earth, and had a scended for the salvation of sinners,

and was now returning to earth again in the form of dew.” Turner took this to mean

that “the Saviour was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men,”

signaling that “the great day of judgment was at hand.” Turner also reported sharing

his visions with a white man named Etheldred T. Brantley, who, upon hearing them,

was attacked with a “cutaneous eruption” that could only be healed by nine days of

fasting and prayer. This apparently only strengthened Turner’s conviction that he

had become a messenger of God and had been called to undertake a revolution.

Nearly thre e years after that, on May 1 2, 1828, Turner h ad a third vi sion. On

this occasion, Turner claimed that he was visited by a spirit from heaven that

instructed him to “ fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching

when the first should be last and the last should be first.” When he was asked, in

his jail cell a fter the rebellion (where Turner recounted these events to Thomas

Ruffin Gray), if he found himself mistaken about what he had seen, Turner replied

curtly: “Was not Christ crucified?” Turner expected to receive a sign indicating

when he should “commence the gre at work,” and when it did, he would know

the time had come: “I should arise and prepare myself and slay my enemies with

their own weapons,” as he put it.

In February 1831, an eclipse of the sun occurred, and Turner took it to be a sign

that he should begin his insurrection. He began to share his plans with four other

Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831) 271

slave s whom he identified as Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam, and together they

planned to carry out their attack on July 4. When Turner fell ill at the appointed

time, the insurrection was abruptly pos tponed, but n ot canceled. A little over a

month later, on August 13, another atmospheric disturbance occurred. This time,

Turner and his men were ready. They went into the woods a week later, on

August 21, to eat and drink and make their plans. At the rendezvous point, the

men w ere joined by two other s laves n amed Will and Jack. Suspicious of their

motives f or being there, Turner asked Will what had made him want to join the

group of rebels. “He answered,” Turner said, that “his life was worth no more than

others, and his liberty as dear to him.” When Turner asked Will if he hoped to

obtain his freedom, Turner said that Will replied “he would, or lose his life.”

The Rebellion

The group emerged from the woods at two o’clock the following morning to make

their way to the home of Joseph Travis, whom Turner described as “a kind master”

who had “placed the greatest confidence” in him. In fact, at the time, Turner was

technically owned by Travis’s stepson, a child named Putnam Moore, whose

mother wa s the widow of Turner’s previous owner, Thomas Moore. It was at the

Travis home that the insurrection began.

The plan was set: “until we had armed and equipped ourselves and gathered

sufficient force,” Turner later said, “neither age nor sex was to be spared”—in

other words, not even women and children would be spared by the insurrectionists.

Turner reported that he “placed fifteen or twenty of the best armed and most to be

relied on in fr ont” after the first attacks to strike terror into the inhabitants of the

homes the slaves attacked and to prevent the escape of any of their victims. Turner

positioned himself at the rear of the phalanx of attacking slaves, where, as he put

it, he sometimes “got in sight in time to see the work of death completed,” and

to have “viewed the mangled bodies as they lay, in silent satisfaction.”

Turne r described the murders committed by the slaves in gruesome detail. He

described the murder of men and women who were still in their beds, said many

times that victi ms barely had time to utter a word be fore being clubbed to death,

andevendescribedhowtwomembersofthegroupreturnedtotheTravishome

to complete their grisly work there after realizing that they had left a sleeping baby

untouched. Turner described murdering a woman named Mrs. Waller and 10 chil-

dren, then proceeding to the home of William Williams, where Williams and two

young boys were k illed while their mother fled. According to Turner, she was

returned to the home and instructed to lay beside her dead husband, “where she

was shot dead.” H e described being unable to kill one woman because his sword

blade was too dull; she was finally killed by Will. At the home of a Mrs. White-

head, Turner found the woman’s daughter, Margaret, hiding near the cellar

272 Nat Turner ’s Rebellion (1831)

outside. “On my a pproach, she fled,” Turner reported, “but was soon overtaken,

and afte r repeated blows with a sword I killed her by a blow on the head with a

fence rail.”

Before it was all over, nearly 60 white men, women, and children had been mur-

dered by Turner and the slaves who had joined him. “ ’Twas my object to carry ter-

ror and devastation wherever we went,” Turner allegedly told Thomas Gray, and in

this respect, the rebellion was a very successful one indeed.

Retribution

Response to word of the insurrection was swift and extensive: the state of Virginia

dispatched local militia, three companies of artillery, and even detachments of

men who were stationed aboard naval vessels at Norfolk to suppress the rebellion.

Whites from neighboring North Carolina also joined the assembling force. In the

immediate aftermath of the killings perpetrated by Turner and the slaves who

had joined him, information was limited, and rumors spread quickly. Needless to

say, rural Virginia in the 1830s lacked such modern amenities as telephones and

other modes of communication. The discoveries made by whites investigating

and hoping to suppress the rebellion were undoubtedly augmented and embel-

lished by those who recounted them to others, only adding to the panic that had

engulfed white Virginians. One Richmond newspaper reported that the Southamp-

ton insurrection was part of a larger group of rebellions carried out as far away as

Alabama.

As a result, the paper’s editor reported, hundreds of slaves a nd perhaps even

some free blacks were slaughtered without trial and with a level of malice and bar-

barity that rivaled the murders committed by Turner and his cohorts. The murders

continued for several days, even weeks, after the rebellion had been put down. A

Lynchburg newspaper reported that a regiment of troops had been commanded to

carry out the murders of more than 90 blacks. They had also killed the slaves’ pre-

sumed leader, then cut off his limbs and hung them separately to inspire terror in

the remaining slaves in the area. A minister writing in the New York Post reported

correctly that the number of blacks kille d in the aftermath of the rebellion would

never be known.

Meanwhile, Nat Turner evaded capture for over two months while his coconspi-

rators were rounded up, one by one. This, as historian Scot French has noted, only

raised Turner’s stature. He was finally captured on October 30, when a dog found

him hiding in a cave near the Travis plantation where he had been held as a slave.

While he was in jail awaiting his trial and eventual execution, Turner was visited

by Thomas Ruffin Gray, a white lawyer determined to capture Turner’s story and

have it published so that white people in Virginia and elsewhere could begin to

understand what had happened. Describing Turner, Gray wrote: “The calm,

Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831) 273