Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Smallpox

Smallpox is an extremely contagious disease caused by the variola virus. Its symp-

toms include a high fever, headache, backache, nausea, vomiting, convulsions, and

pus-filled corpuscles all over the body. Due to the incubation period of the disease,

which on average exceeds 10 days, a person unknowingly exposes others to small-

pox before the obvious symptoms appear. The disease e ither kills the afflicted

individuals or leaves them horribly scarred. From the time smallpox was first

introduced to the Americas by European colonizers, it proved particularly deadly

among Native American populations because they had not had previous exposure

to the variola virus in any form.

During Pontiac’s Rebellion, the defenders of Fort Pitt famously engaged in bio-

logical warfare through the use of smallpox. On June 24, 1763, Delaware negotia-

tors Turtle’s Heart and Mamaltee were given two blankets and two silk

handkerchiefs as gifts by British dignitaries at Fort Pitt. Since gift giving was an

established tradition during negotiations, the Delawares accepted the items gra-

ciously from their hosts. The British had intentionally obtained the four items

from their hospital, which was treating quarantined smallpox patients, with the

hope that a smallpox epidemic would erupt among the many Native American

groups that were besieging the fort. Within the m onth, a smallpox epidemic had

erupted among native peop les throughout the Ohio Vall ey and the Great Lake s

region.

General Jeffrey Amherst, Great Britain’s commander in chief in North

America, has historically been credited with devising the plan to use smallpox as

a biological agent against the Native Americans at Fort Pitt. In truth, there are no

known records that definitively identify who originated the idea. T he most likely

culprit was Captain Simeon Ecuyer, who commanded the garrison at Fort Pitt.

Undoubtedly, both Amherst and his subordinate Colonel Henry Bouquet approved

of the course of action, because both were openly advocating spreading smallpox

as a military strategy by July 1763. The very fact that high-level British officers

advocated the use of smallpox to attack their enemies was illustrative of the initial

successes of the Native Americans besieging the British forts becaus e, under the

European conventions of war of the day, such an act was considered an atrocity.

It may be too simplistic to credit the outbreak of smallpox among Nativ e Americans

in 1763 solely to the defenders of Fort Pitt when one considers that the presence of

afflicted individuals in the fort’s hospital suggests that there were probably others

afflicted with the disease in the region that were not showing symptoms due to the

virus’s incubation period. Irrespective of the number of potential sources for the

124 Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763)

smallpox epidemic of 1763, its toll on the nati v e warriors and their home commun-

ities helped Great Britain to quell Pontiac’s Rebellion.

—John R. Burch Jr.

Further Reading

Fenn, Elizabeth A. “ Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond

Jeffery Amherst.” Journal of Americ an History 86 (2000): 1552–1580.

Kelton, Paul. Epidemics and Enslavement: Biological Catastrophe in the Native Southeast

1492–1715. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 200 7.

Kiple, Kenneth F., ed. The Cambridge World History of Human Disease.NewYork:

Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763) 125

Stamp Act Protests (1765)

Nonviolent Stamp Act protests began in 1607 when the first English settlers came

ashore in New England. They understood their relationship with London. Having

being nurtured by the Crown, these pioneers concerned themselves with survival

under the protection of England. Fortunately, London through its largess adopted

a policy of “salutary neglect,” permitting the growing number of colonies and their

populations to develop a newly unique culture. Parliament’s colonial expansion

initiated the dawn of a new age.

As time passed, these colonists began to identify themselves with their colony

and gave less thoug ht and consideration to their traditional rights as Englishmen.

They legislated new and more rigid laws, some of which contradicted the English

and nascent American common law. In many cases, such as the witchcraft trials,

the defendant’s guilt was assumed, and she had to prove her innocence in an envi-

ronment less than just.

These rights, n ot challenged, became an increasingly important issue after

British successes in the French a nd Indian War in sparsely settled areas west of

the colonies. A British achievement in clearing the region of the French “menace”

in 1763 was viewed favorably by London. Settlers moved west of the mountains,

with or without Crown permission, further removing themselves from English

culture.

Having bank rupted the Exchequer bec ause of the colonial w ars, having had to

muster sufficient forces to protect the colonies, and maintaining a fleet to prevent

the French from dominating trade and the seas, the Crown changed its conduct

toward the c ol onie s. Financial needs requ ired Parliament t o remold its attitudes

toward her English subjects. Since the colonials generally paid few taxes, the

Stamp Act provided a means of returning the Empire to fiscal solvency. First

attempts included the Americ an Revenue Act, also known as the Sugar Act, and

the extension of the Molasses Act of 1733 were quite comprehensive but did not

resolve the problem. In 1764, George Grenville strengthened the Imperial Custom

Service, allowing for tighter enforcement regulations against smuggling. Grenville

also modified the Currency Act.

This change of circumstances is illustrated by Parliament’s passage of the

Stamp Act by 245–49 on February 6 (29), 1765, when Grenville presented his

Stamp Act Bill. The House of Lords approval the Act on March 8 and the king

127

on March 22. It was ordered into effect two weeks later. The debt had grown from

72-plus million pounds to 129-plus million shortly before the act went into effect.

The restiveness of the English population because of the high taxes it paid was

causing the Crown concern with a possible revolution.

The Stamp Act, the first direct parliamentary tax, numbed colonials who lived

in “splendid Isolation.” In one moment, the 63 pages of the Stamp Act Orders

cha nged the landscape for the colonies; the colonials were informed that the tax

would be used for colonial administration. Direct means of collection were

imposed because London realized prior relations could make application of the

new laws a controversial matter. Legal documents of all sorts, newspapers, and

apprenticeship status were taxed. Merchants and others who would trade in prom-

issory or other forms of financial notes, such as transportat ion documents, were

most vulnerable.

At the same time that the Stamp Act became l aw, the Crown also passed the

Quartering Act. Fearful of civil disobedience, the Crown sent large detachments

to Boston and other commercial and mercantile centers. The colonials had to pro-

vide lodgin g and supplies for soldiers garrisoning in colonial homes. A second

Quartering Act required the billeting of soldiers in inns, almshouses, and unoccu-

pied dwellings.

128 Stamp Act Protests (1765)

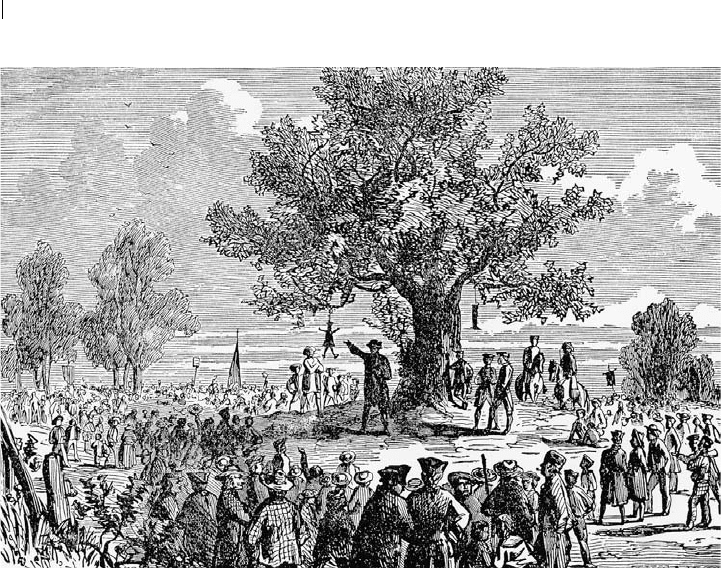

Stamp Act rioters hang a stamp distributor in effigy in 1765. (North Wind Picture Archives)

Such legislation ignited the events that led to a family separation. The colonies

never had voting representations in Parliament, which passed laws for the benefit

of the Empire. The colonials had experienced the effect of legislation prior to the

Stamp Act, but the harshness of the act encompassed all avenues of income pro-

ducing taxation.

When colonial leaders opposed the act as i llegitimate, the members of the

colonial community mostly affected resorted to “n o taxation without representa-

tion.” Calls arose to protect the traditional rights of Englishmen as evidence d by

the Magna Carta of 121 5 and the Bill o f Rights of 1689 t hat had forb idden the

imposing of taxes without the consent of parliament. When protests rose from civil

disobedience to physic al action, London answered with Blackstone’s theory of

“virtual representation.” The concept was clear: Parliament in London made laws

governing the Empire, and since the colonials were British subjects, they were

bound by its legislation.

The theory of “virtual representation” affirmed the legality of control over

colonial affairs. But, Parliament was not representative of all classes of society

as land requirements and other restrictionslimitedmembershipintheHouseof

Commons such that approximately only 3 percent of the men could vote: only

Anglicans, and wealthier elements in land and commer ce of society. The Crown

and Parliament justified their actions by reminding the colonies of the aid and

protection they had received on land and sea. Since the English taxpayer bore

the burden of supporting the colonies, Parliament had to act. Prime Minister Lord

George Grenville advocated the tax by arguing that geography did not matter, but

the Empire as a whole suppor ted all English subjects, whether in Lond on or the

colonies. The colonies argued that true representationoccurredonlywhenone

was present and allowed to vote for or against any pa rticul ar legislation, a view

contrary to this parliamentary decision.

This ideological loggerhead frustrated the Crown and associated it with the civil

disobedience of the colonies. Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765. The com-

prehensive act addressed every possible source of income for the Crown. Unfortu-

nately, many of its provisions affected the educated and politically astute

colonials, many of whom had studied history and geography. This small minority

of the population had the capacity to arouse the general public with arguments

challe nging the Crown’s demands. For example, having to pay higher duties as a

result of t he legislation meant every legal document had to carry a tax stamp to

be legal.

One of many, Isaac Barre, a veteran of the French and Indian War, responded

negatively to Parliament. He offered the colonial viewpoint to Parliament. He

reminded t he august body of the colonial contributions in fighting the French

and Indians. His minority views failed to alter the situation, and instead, the

Stamp Act Protests (1765) 129

colonies were called upon to support the Empire and not selfi shly concern them-

selves. Parliament reinforced its new attitude toward the colonies by its conduct.

Benjamin Franklin, colonial American representative th en living in London,

met with Prime Minister Lord Grenville prior to the Stamp Act’s approval.

Franklin and others asked the British to reconsider their plan. Lord Grenville

offered an alternative. He proposed that the colonial assemblies tax themselves

to pay the costs involved for keeping the Bri tish in North America. The problem

with this potential solution was that none of the colonials in London had authority

to negotiate. The offer was declined without submission to the various colonial

assemblies.

Samuel Ad ams referred to a spontaneous rea ction, and through his influence,

the Massachusetts Assembly approved his instructions, and copies were sent to

all t he colonies. Colonial governor Francis Bernard opposed the efforts to unite

all the colonies i n an effort to protest the Stamp Act. The governor understood

the consequences of the call for colonial unity, stating that “demagoguery” was

the aim of this conduct. He also alleged that joint action i n opposition to the act

was against the rights of the people. He didn’t explain the reasons for h is

allegations. But, the governor saw the ec onomic class of the protesters was not

“meddling,” but members of aristocratic and wealthy commercial interests.

James Otis appeared more of a legalist and writer than other revolutionary lead-

ers and wrote A Vindication of the British Colonies in 1765. His early views were

not generally accepted, but he served in the Stamp Act C ongress, advocating

colonial representation in Parliament and conceding its supremacy. As an attorney,

he opposed the issuance of a Writ of Assistance—a general warrant issued before

the crime—to assist in the enforcement of the Sugar Act.

Thomas Paine, writing anonymously, sent a large number of copies of his

Common Sense throughout the co lonies. He advocated an immediate declaration

of independence on practical, ideological, and legal grounds. Later, he joined the

Revolutionary army and took part in the retreat across New Jersey.

Patrick Henry, in the Virginia House of Burgess, on May 30, 1765, carried the

legal issues to the fore. He made his famous, or infamous, “Caesar had his Brutus,

Charles I his Cromwell” speech. As a result, the Burgesses resolved “it had the

sole and exclusive right to lay taxes ...upon the inhabitants of this colony ...

who were not bound to yield obedience to any law of parliament attempting to

tax them.”

The act’s preamble s tated its purpose: defraying Crown cost and expenses for

defending the western frontiers against the French and Indians and British com-

merce agains t the French. Foreign trade was a particular concern. The e stablish-

ment of Admiralty Courts in 1763 and then Vice-Admiralty Courts represented

Crown concern over revenue. The first Admiralty Act gave the Crown wide

130 Stamp Act Protests (1765)

jurisdiction over laws affecting the colonies that were expanded by the Stamp Act

of 1765. Since these courts were not common-law courts, Admiralty trials were

not considered within the scope of the “rights of Englishmen.” Therefore, the

Magna Carta did not protect them with the right to a trial by jury. The acts’ provi-

sions agitated the colonies. Jurisdiction could be anywhere in the Empire. Judges

received a percentage of the fines levied, and naval officials were compensated

for successful prosecutions. Defendants had no right to trial by jur y, and the evi-

dence requirements were slack.

This effort to improve the collection of revenue and taxes w as highly res ented

and became a cause ce

´

le

`

bre to those opposing the Stamp Act. Smugglers had

avoided paying taxes and, like the Peter Zenger Case, the jury would probably

vote against the Crown. Vice-Admiralty Courts had concurrent jurisdiction; these

courts heard conflicts between merchants and seamen. Its judges were appointed

by the Crown and came from England. Its jurisdiction covered the entire east coast

of the American colonies. Contrary to existing law, the de fenda nt was presumed

guilty. One’s failure to appear resulted in an automatic guilty verdict, even if the

defendant could not travel to the court for the hearing.

With such threats to commerce, the Massachuset ts Colonial Assembl y sent a

circular letter to all of the colonies in June 1765. All those invited had previously

served in colonial assemblies and understood parliamentary procedures. Nine col-

onies responded to this first American call to the Stamp Act Congress. The various

attendees realized their attitudes were all similar. A proposal was made that colo-

nials be appointed members of parliament. The concept of the colonial assem-

blies’ managing their own financial matters and concern over the number of

Loyalists who could be sent to London dissuaded its propo nents. The suggestion

went nowhere, but what would have happened if London had agreed?

Colonials had supported King George III, but t he provisions of the Stamp Act

proved burdensome. As t he cry of “no taxation without representation” spread,

and no revenues were collected, Lord Pitt in Parliament opposed the act, and the

Crown eventually repealed it. Having evidenced its weakness to colonial resis-

tance, London passed the Declaratory Acts asserting her dominion over the

American colonies, but to what effect? The issue now moved from a solely eco-

nomic matter to a legal, constitutional issue defining the rights of British subjects.

On August 14, 1765, the first manifestations against the Stamp Act occurred

when tax collectors were hung in effigy in the Boston Commons. A crowd of mer-

chants, skilled craftsmen, and other directly interested parties—financially and

politically—led the crowd in a protest against the Crown’s interference in colonial

affairs. Within a short time, colonials—women, skilled and unskilled workers, and

(freed) slaves—gathered at the Liberty Tree to express their anger over the British

imposition. Liberty trees became symbols of resistance and appeared throughout

Stamp Act Protests (1765) 131

the colony. November 11, Pope’s Day, wa s selected for the protest. This enabled

the populace to g ather gleefully; the anti-Catholic Protestants used this day to

hang the pope in effigy, set fires, and have brawls throughout the city. The lower,

and poorer, classes used this day not as a response to the Stamp Act but as a

vehicle for augmenting their age-old prejudice against Rome.

Two effigies appeared; one represen ted Andrew Oliver, th e Boston Stamp Act

Commissioner and t he brother-in-law of the colony’s second-highest official,

Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. The other, a boot, represented a

parliamentarian, the Earl of Bute, the innovator of the Stamp Act. When the crowd

gathered, the public response initially was mockery, which quickly adopted a

political overtone. The crowd went through the city “stamping” everything; i t

was large and composed of artisans, male and female laborers, children, a few

merchants, and a few gentlemen. The effigies were hung to shouts of “liberty,

property, and no stamps.” The crowd went to the stamp office and tore the building

down. Crown officials became concernedatthedisorderandallmarchedtothe

Liberty Tree.

Zachariah Hood, the Boston tax collector, had to flee. The mob had burned his

stamps, and he rode to New York for the protection of the English garrison. Riding

his horse to death en route, Hood entered a colony that opted for the nonimporta-

tion of goods from England.

The mob’s mood changed. Its organizers had lost control of the crowd, and the

public officials now became concerned. When a bonfire was lit, an unruly crowd

assembled. The object of the anger was Thomas Hutchinson, who was one of the

most unpopular figures in Boston and the symbol for all that the mob opposed.

His home was ravaged while a large gathering stood by and did nothing. Samuel

Adams, an ardent revolutionary, understood the importance of the rioting, and he

publicly disavowed knowledge or participation.

In every seaport, groups formed were composed of the “middle class.” The Sons

of Liberty dressed as workmen and sailors, probably to conceal their middle-class

status. They forced Stamp Act distributors to destroy their materials and resign

under threat of harm. They also a tta cked those deemed conspirators of the a ct’s

acceptance. When the act came into effect on November 1, 1765, the apparatus

existed to forcibly resist. Colonial Governor Colden had to flee the city; his home

was destroyed and carriage burned. He sought refuge on a British vessel. The pro-

testers then marched across the city and attacked the garrison commander’s home,

destroying everything in sight.

The insurrection continued to spread. In North Carolina, for example, Ro yal

Governor William Tryon, famous for the Regu la t or revolt, promised t he leading

merchants and planters special privileges should they obey the Stamp Act. He

promised to write London for special privileges for these 50 individuals and

132 Stamp Act Protests (1765)

promised to reimburse them for their expenses c aused by the stamp tax. Tryon

refused to allow the colonial ass embly to convene. Despite his object ions, most

North Carolinians refused to pay the tax, so royal officials closed Cape Fear River

port and others. One thousand Carolinians traveled to Wilmington to confront the

tax collector, William Dry, who refused to let vessels pass since they had

unstamped clearance papers.

North Carolinians forced the North Carolina Gazette editor to issue

unstamped editions. The editor made “inflammatory expressions” about the

Stamp Act, and the governor hired another newspaper as its official printer.

The royal governor tried to enforce the a ct, and his efforts to quell resistance

increased the popularity of the Sons of Liberty. In the February 26 , 1766, edi-

tion, after declaring its loyalty to the Crown, it related historical freedoms

granted the colonies and ended by stating its intent to “prefer death to slavery.”

The Gazette called for peaceful protests, if possible. All freeholders entered into

a compact to resist by unity of the colonies.

Charleston, South Carolina, another notable port city, did not escape the may-

hem. Henr y Laurens, a leading membe r of the community who was wealthy in

land and commerce, received the crowd’s venom. His residence was searched for

Stamp Act stamps. In Newport, Rhode Island, the Sons of Liberty paid someone

to terrify the stamp distributors and local customs collectors.

Street violence burst forth in Newport in August. Gallows were built, and effi-

gies were hung of Augustus Johnson, the stamp distributor, and two other leading

conservative figures in the colony. The mob then attacked homes and destroyed

property. The Sons of Liberty opposed violence, but were threatened if they inter-

fered. There were other protests: Maryland, Georgia, and Pennsylvania leaders all

argued for a rescission of the Stamp Act.

The Sons of Liberty was established in 1765; local groups of protesters

assembled in all the colonies, a unifying action not witnessed before in British-

American colonial history. This intercolonial organization existed in various forms

before 1765. It was i nstrumental in developing a pattern for resistance to the

Crown that led to American independence. The organization communicated with

all the colonies. On November 6, a committee in New York began intercolonial

correspondence with the various colonies and they all expressed an interest in joint

action to protect their “legal and legitimate rights.”

The Sons of Liberty’s membership, an engine in the struggle to rebalance the

relationship of the mother country with her North American children, was com-

posed of financially comfortable subjects whose personal interests were greatly

affected. The declared intention to enlarge the base of colonial participation may

have been ingenious; most colonials, being uneducated, reacted and accepted the

verbiage of the aforementioned. Symbolic of the effort, the Sons of Liberty strove

Stamp Act Protests (1765) 133