Carranza E. Geochemical anomaly and mineral prospectivity mapping in GIS

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Knowledge-Driven Modeling of Mineral Prospectivity 203

mean of the CVs is an estimate of λ. The deviation of λ from n (i.e., maximum

eigenvalue) in a situation of a consistent n×n matrix is used to define a consistency index

(CI), which in turn is used to define a consistency ratio (CR) (Table 7-III). The CR is

obtained by comparing CI to a random inconsistency index (RI) of a n×n matrix of

randomly generated pairwise importance ratings (Table 7-IV). If the value of CR is

greater than 0.1 (i.e., CI > 10% of RI), then the inconsistencies in a pairwise comparison

matrix are unacceptable so that a re-evaluation of the pairwise relative importance

ratings of the criteria is in order. The results shown in Table 7-III indicate that

inconsistencies in the pairwise comparison matrix (Table 7-I) for the epithermal Au

prospectivity recognition criteria in the case study area are within acceptable limits,

meaning that the values of W

i

(Table 7-II) can be relied upon in deriving a meaningful

epithermal Au prospectivity map via application of the binary index overlay modeling.

The epithermal Au prospectivity map of the case study area derived via binary index

overlay modeling and shown in Fig. 7-6A was obtained by assigning the following

weights (values in bold) to the individual evidential maps:

4: presence of multi-element stream sediment geochemical anomalies.

4: proximity to (within 0.35 km of) NNW-trending faults/fractures.

2: proximity to (within 1 km of) intersections of NNW- and NW-trending

faults/fractures.

1: proximity to (within 0.9 km of) NW-trending faults/fractures.

TABLE 7-III

Estimation of consistency ratio (CR) for judgment of consistency of pairwise ratings o

f

recognition criteria for epithermal Au prospectivity in Aroroy district (Philippines). Values in bold

italics are taken from Table 7-I. Underlined values are taken from Table 7-III.

Criteria

1

NNW FI NW ANOMALY Sum

2

Consistency

vector (CV)

3

NNW

0.39 × 1

= 0.39

0.19 × 5

= 0.95

0.09 × 6

= 0.54

0.34 × 1/2

= 0.07

1.95 5.00

FI

0.39 × 1/5

= 0.08

0.19 0.45 0.07 0.79 4.16

NW

0.39

× 1/6

= 0.07

0.07 0.09 0.07 0.27 3.00

ANOMALY

0.39

× 2

= 0.78

0.38 0.18 0.14 1.48 4.35

λ = mean of CV = 16.51/4 = 4.13

Consistency Index (CI) = (λ-n

criteria

)/(n

criteria

-1) = (4.13-4)/(4-1) = 0.043

Consistency Ratio (CR) = CI/RI

4

= 0.043/0.9 = 0.048

1

See footnotes to Table 7-I.

2

Example: Sum

NNW

= 0.39 + 0.95 + 0.54 + 0.07 = 1.95.

3

Example:

CV

NNW

= Sum

NNW

÷ Weight

NNW

= 1.95 ÷ 0.39 = 5.00.

4

RI = Random inconsistency index. See

Table 7-IV for RI values corresponding to n

criteria

.

204 Chapter 7

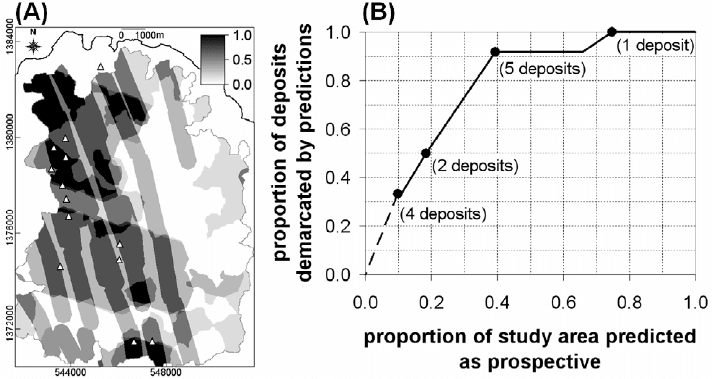

The heavier weights on proximity to NNW-trending faults/fractures and stream

sediment multi-element anomalies are evident in the output map of the binary index

overlay modeling (Fig. 7-7A), although the pattern of the predicted most prospective

areas (in black) is strongly similar to the pattern of the prospective areas predicted by

application of Boolean logic modeling (Fig. 7-5A). This indicates that the pairwise

ratings given to the stream sediment anomalies with respect to the individual structural

criteria are consistent with the importance given to the former in the way the evidential

maps are combined via Boolean logic modeling (see inference network in Fig. 7-4).

Like the application of Boolean logic modeling, the application of binary index

overlay modeling returns an output value only for locations with available data in all

input evidential maps. Thus, for the case study area, locations with missing stream

sediment geochemical data do not take on prospectivity values by application of binary

index overlay modeling (Fig. 7-7A). So, one of the 13 known epithermal Au deposit

occurrence is not considered in the cross-validation of the prospectivity map.

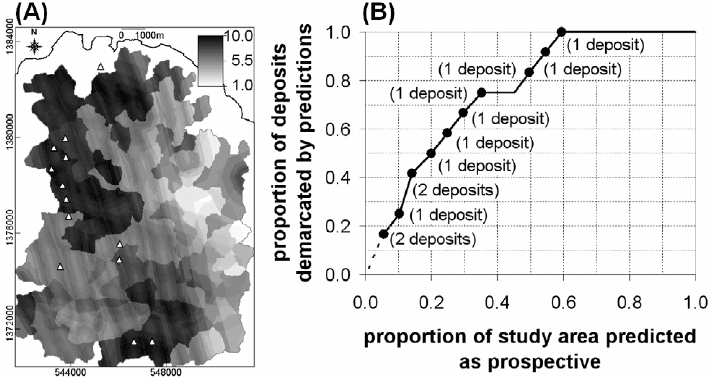

The prospectivity map derived via binary index overlay modeling is better than the

prospectivity map derived via Boolean logic modeling because the former delineates all

cross-validation deposits in about 75% of the study area (Fig. 7-7B) whilst the latter

delineates all cross-validation deposits in at least 85% of the case study area (Fig. 7-5B).

However, both prospectivity maps are similar in terms of prediction-rate (roughly 40%)

of a prospective area equal in size (about 14% of the case study area) to that predicted by

application of the Boolean logic modeling.

Calibration of predictive modeling with binary evidential maps

Because of the very limited range of evidential class scores that can be assigned to

classes in a Boolean or binary map, probably the best method calibration is to perform a

number of changes in the threshold values specified by the conceptual model of mineral

prospectivity. This results in changing the areas of evidential classes in a Boolean or

binary map. In Boolean logic modeling, another method for calibration is to modify the

inference network, whilst in binary index overlay modeling another method for

calibration is to modify the evidential map weights. Because any set of changes would,

in turn, correspond to a change in prediction-rate of prospective areas, the objective of

any strategy for predictive model calibration is to find a set of modifications in the

modeling that corresponds with prospective areas having the highest prediction-rate.

However, in any strategy for calibration of predictive modeling using binary evidential

TABLE 7-IV

Some random inconsistency indices (RI) generated by Saaty (1977) for a large number of n×n

matrices of randomly generated pairwise comparison ratings

n 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

RI 0 0 0.58 0.9 1.12 1.24 1.32 1.41 1.45 1.49

Knowledge-Driven Modeling of Mineral Prospectivity 205

maps, one must consider the significance of any modifications made in the modeling in

terms of the geologic controls on mineral occurrence and/or spatial features that indicate

the presence of mineral deposit occurrence.

It is clear from the above examples that binary index overlay modeling is more

advantageous than Boolean logic modeling, especially in terms of producing a realistic

multi-class output instead of a synthetic binary output. We now turn to predictive

modeling techniques, whereby evidential maps can take on more than two classes of

evidence of mineral prospectivity. These ‘multi-class’ modeling techniques provide

more flexibility in assignment of evidential class scores than the ‘two-class’ techniques

described so far.

MODELING WITH MULTI-CLASS EVIDENTIAL MAPS

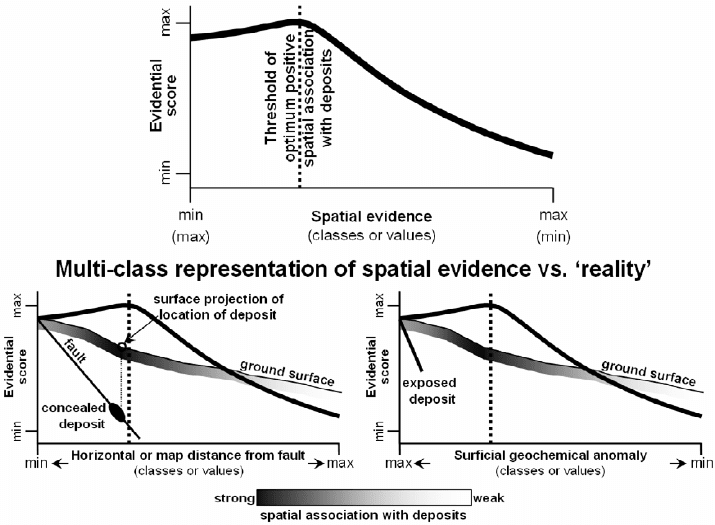

In this type of modeling, evidential maps representing prospectivity recognition

criteria contain more than two classes (Figs. 7-1 and 7-8). Individual classes or ranges of

values of evidence in an evidential map are hypothesised to have different degrees of

importance relative to the proposition under consideration and therefore are given

different scores depending on the concept of the spatial data modeling technique that is

applied. Highest evidential scores are assigned to classes of spatial data portraying

presence of indicative geological features and varying about the threshold spatial data

Fig. 7-7. (A) An epithermal Au prospectivity map obtained via binary index overlay modeling,

Aroroy district (Philippines) (see text for explanations about the input evidential maps used).

Triangles are locations of known epithermal Au deposits; whilst polygon outlined in grey is area

of stream sediment sample catchment basins (see Fig. 4-11). (B) Prediction-rate curve o

f

p

roportion of deposits demarcated by the predictions versus proportion of study area predicted as

prospective. The dots along the prediction-rate curve represent classes of prospectivity values that

correspond spatially with a number of cross-validation deposits (indicated in parentheses).

206 Chapter 7

value representing optimum positive spatial association with mineral deposits of the type

sought. Reduced and lowest evidential scores are assigned to spatial data representing

increasing degrees of absence of indicative geological features and increased lack of

positive spatial association with mineral deposits of the type sought. So, there is a

continuous range of minimum-maximum evidential scores in modeling with multi-class

evidential maps. This knowledge-based representation is more-or-less consistent with

real situations. For example, whilst certain mineral deposits may actually be associated

with certain faults, the locations of some mineral deposits indicated in maps are usually,

if not always, the surface projections of their positions in the subsurface 3D-space,

Fig. 7-8. Knowledge-based multi-class representation of spatial evidence of mineral prospectivity.

Knowledge of spatial association between mineral deposits of the type sought and spatial data o

f

indicative geological features is applied to assign evidential scores (upper part of the figure). I

f

classes or values of spatial data vary about the threshold spatial data of optimum positive spatial

association with mineral deposits of the type sought, they are given close to maximum evidential

scores of mineral prospectivity; otherwise, they are given scores decreasing to the minimum

evidential score of mineral prospectivity. These scores are continuous (i.e., they vary from

minimum to maximum). Multi-class representation of spatial evidence is more-or-less consistent

with real situations of spatial associations between mineral deposits and indicative geological

features. For visual comparison, the graph in the upper part of the figure is overlaid on schematic

cross-sections of ground conditions (lower part of the figure), but the y-axis of the graph does

represent vertical scale of the cross-sections. See text for further explanation.

Knowledge-Driven Modeling of Mineral Prospectivity 207

whereas the locations of faults indicated in maps are more-or-less their ‘true’ surface

locations. Thus, for locations within the range of distances to certain faults where the

positive spatial association with mineral deposits is optimal, the evidential scores

assigned are highest but these scores decrease slowly from maximum at the threshold

distance to a lower score at the minimum distance (Fig. 7-8). For locations beyond the

threshold distance to certain faults, where the positive spatial association with mineral

deposits is non-optimal, the evidential scores assigned decrease rapidly from maximum

at the threshold distance to the minimum evidential score at the maximum distance. The

same line of reasoning can be accorded to multi-class representation of evidence for the

presence of surficial geochemical anomalies, which may be significant albeit

allochthonous (i.e., located not directly over the mineralised source) (Fig. 7-8). Note,

therefore, that the graph of multi-class evidential scores versus data of spatial evidence is

more-or-less consistent with the shapes of the D curves (Figs. 6-9 to 6-12) in the

analyses of spatial associations between epithermal Au deposit occurrences and

individual sets of spatial evidential data in the case study area. Thus, multi-class

representation of evidence of mineral prospectivity is suitable in cases where the level of

knowledge applied is seemingly complete and/or when the accuracy or resolution of

available spatial data is satisfactory. We now turn to the individual techniques for

knowledge-based multi-class representation and integration of spatial evidence that can

be used in order to derive a mineral prospectivity map.

Multi-class index overlay modeling

This is an extension of binary index overlay modeling. Each of the j

th

classes of the

i

th

evidential map is assigned a score S

ij

according to their relevance to the proposition

under examination. The class scores assigned can be positive integers or positive real

values. There is no restriction on the range of class scores, except that the range of class

scores in every evidential map must be compatible (i.e., the same minimum and

maximum values). This means that it is impractical to control the relative importance of

an evidential map in terms of the proposition under consideration by making the range of

its class scores different from the range of class scores in another evidential map. The

relative importance of an evidential map compared to each of the other evidential maps

is controlled by assignment of weights W

i

, which are usually positive integers. Weighted

evidential maps are then combined using the following equation, which calculates an

average weighted score (

S ) for each location (Bonham-Carter, 1994):

¦

¦

=

n

i

i

n

i

iij

W

WS

S

(7.2)

The output value

S for each location is the sum of the products of S

ij

and W

i

in each

evidential map divided by the sum of W

i

for each evidential map. Recent examples of

208 Chapter 7

multi-class index overlay modeling applied to mineral prospectivity mapping can be

found in Harris et al. (2001b), Chico-Olmo et al. (2002), De Araújo and Macedo (2002)

and Billa et al. (2004).

Examples of scores assigned to classes in individual evidential maps representing the

recognition criteria for epithermal Au prospectivity in the case study area are listed in

Table 7-V. The evidential maps of proximity to structures each contain 10 classes

obtained by classifying the range of map distances to a set of structures into 10-

percentile intervals. The scores assigned to proximal classes within the range of distance

of optimum positive spatial association with known epithermal Au deposits are

substantially higher than the scores assigned to distal classes. The evidential map of

multi-element stream sediment geochemical anomalies contains only eight classes

because the lowest values represent 30 percentile of the data and the remaining values

are classified into 10-percentile intervals. The scores assigned to the upper 30 percentile

classes, which have optimum positive spatial association with known epithermal Au

deposits, are substantially higher than the scores assigned to the lower 70 percentile

classes. The individual evidential maps are assigned the same weights (W

i

) as those used

in the binary index overlay modeling (see Table 7-II).

The prospectivity map derived via multi-class index overlay modeling (Fig. 7-9A)

shows the influence of the catchment basin stream sediment multi-element anomalies

and NNW-trending linear patterns indicating the influence of proximity to the NNW-

trending faults. These indicate consistency of the slightly higher pairwise importance

rating given to the stream sediment anomalies compared to the proximity to NNW-

TABLE 7-V

Examples of scores assigned to evidential classes in individual evidential maps portraying the

recognition criteria for epithermal Au prospectivity, Aroroy district (Philippines). Range of values

in bold include the threshold value of spatial data of optimum positive spatial associations with

epithermal Au deposits in the case study area.

Proximity to NNW

1

Proximity to FI

2

Proximity to NW

3

ANOMALY

4

Range (km) Score Range (km) Score Range (km) Score Range Score

0.00 – 0.08 8.0 0.00 – 0.39 8.0 0.00 – 0.18 8.0 0.00 – 0.06 1.0

0.08 – 0.15 8.5 0.39 – 0.58 9.0 0.18 – 0.36 8.5 0.06 – 0.10 2.0

0.15 – 0.23 9.0 0.58 – 0.80 9.5 0.36 – 0.54 9.0 0.10 – 0.16 4.0

0.23 – 0.32 9.5

0.80 – 1.09

10.0 0.54 – 0.75 9.5 0.16 – 0.25 6.0

0.32 – 0.41

10.0 1.09 – 1.40 9.0

0.75 – 1.01

10.0 0.25 – 0.29 8.0

0.41 – 0.52 9.0 1.40 – 1.80 7.0 1.01 – 1.29 8.0

0.29 – 0.37

10.0

0.52 – 0.71 7.0 1.80 – 2.32 5.0 1.29 – 1.65 6.0 0.37 – 0.49 9.5

0.71 – 1.06 5.0 2.32 – 2.92 3.0 1.65 – 2.24 4.0 0.49 – 0.78 9.0

1.06 – 1.73 3.0 2.92 – 3.62 2.0 2.24 – 3.02 2.0

1.73 – 3.55 1.0 3.62 – 5.92 1.0 3.02 -5.32 1.0

1

NNW-trending faults/fractures.

2

Intersections of NNW- and NW-trending faults/fractures.

3

NW-

trending faults/fractures.

4

Integrated PC2 and PC3 scores obtained from the catchment basin

analysis of stream sediment geochemical data (Chapter 3).

Knowledge-Driven Modeling of Mineral Prospectivity 209

trending faults/fractures and the higher pairwise importance rating given to the proximity

to NNW-trending faults/fractures compared to the proximity to the other structures (see

Table 7-I). Like the application of Boolean logic modeling and binary index overlay

modeling, the application of the multi-class index overlay modeling returns an output

value only for locations with available data in all input evidential maps. Thus, one of the

13 known epithermal Au deposit occurrence is not considered in the cross-validation of

the prospectivity map.

The prospectivity map derived via multi-class index overlay modeling is better than

the prospectivity map derived via binary index overlay modeling because the former

delineates all cross-validation deposits in 60% of the study area (Fig. 7-9B) whilst the

latter delineates all cross-validation deposits in about 75% of the case study area (Fig. 7-

7B). However, the prospectivity map derived via multi-class index overlay modeling is

similar to the prospectivity maps derived via Boolean logic modeling (Fig. 7-5B) and

binary index overlay modeling (Fig. 7-7B) in terms of prediction-rate (roughly 40%) of a

prospective area of about 14% of the case study area.

The prospectivity maps derived via application of binary and multi-class index

overlay modeling are different mainly in terms of predicted prospective areas occupying

15-40% of the case study area. In this case, the prospectivity map derived via binary

index overlay modeling is slightly better than the prospectivity map derived via multi-

class index modeling. However, this does not indicate the advantage of former technique

Fig. 7-9. (A) An epithermal Au prospectivity map obtained via multi-class index overlay

modeling, Aroroy district (Philippines) (see text for explanations about the input evidential maps

used). Triangles are locations of known epithermal Au deposits; whilst polygon outlined in grey is

area of stream sediment sample catchment basins (see Fig. 4-11). (B) Prediction-rate curve o

f

proportion of deposits demarcated by the predictions versus proportion of study area predicted as

prospective. The dots along the prediction-rate curve represent classes of prospectivity values that

correspond spatially with a number of cross-validation deposits (indicated in parentheses).

210 Chapter 7

over the latter technique because the objective of prospectivity mapping is to delineate

small prospective zones with high prediction-rates. On the contrary, the slightly poorer

performance of the prospectivity map derived via application of multi-class index

overlay modeling compared to that of prospectivity map derived via application of

binary index overlay modeling, with respect to prospective areas occupying 15-40%,

indicates the caveat associated with binarisation of spatial evidence because this is prone

to both Type I (i.e., false positive) and Type II (i.e., false negative) errors. That is, in the

binarisation process, the classification (or ‘equalisation’) of evidential values to either 1

(rather than less than 1 but greater than 0) or to 0 (rather than greater than 0 but less than

1) means that some evidential values are ‘forced’ to become favourable evidence even if

they are not (thus, leading to false positive error) and that some evidential values are

‘forced’ to become non-favourable even if they are not (thus, leading to false negative

error).

Thus, in addition to its flexibility of assigning evidential class scores, multi-class

index overlay modeling is advantageous compared to binary index overlay modeling in

terms of suggesting uncertain predictions. It is therefore instructive to apply both of

these two techniques together instead of applying only either one of them. A

disadvantage of both of these techniques is the linear additive nature in combining

evidence, which does not intuitively represent the inter-play of geological processes

involved in mineralisation. We now turn to fuzzy logic modeling, which, like the

Boolean logic modeling, allows integration of evidence in an intuitive and logical way

and, like the multi-class index overlay modeling, allows flexibility in assigning

evidential class scores.

Fuzzy logic modeling

Fuzzy logic modeling is based on the fuzzy set theory (Zadeh, 1965). Demicco and

Klir (2004) discuss the rationale and illustrate the applications of fuzzy logic modeling

to geological studies; unfortunately, they do not provide examples of fuzzy logic

applications to mineral prospectivity mapping. Recent examples of applications of fuzzy

logic modeling to mineral prospectivity mapping are found in D’Ercole et al. (2000),

Knox-Robinson (2000), Porwal and Sides (2000), Venkataraman et al. (2000), Carranza

and Hale (2001a), Carranza (2002), Porwal et al. (2003b), Tangestani and Moore (2003),

Ranjbar and Honarmand (2004), Eddy et al. (2006), Harris and Sanborn-Barrie (2006),

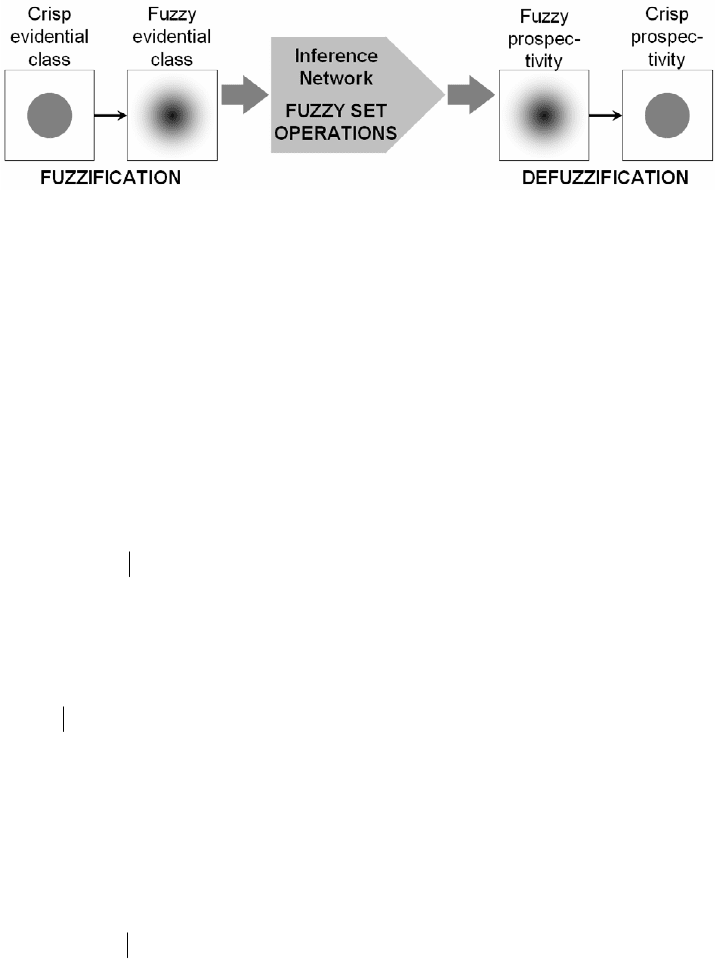

Rogge et al. (2006) and Nykänen et al. (2008a, 2008b). Typically, application of fuzzy

logic modeling to knowledge-driven mineral prospectivity mapping involves three main

feed-forward stages (Fig. 7-10): (1) fuzzification of evidential data; (2) logical

integration of fuzzy evidential maps with the aid of an inference network and appropriate

fuzzy set operations; and (3) defuzzification of fuzzy mineral prospectivity output in

order to aid its interpretation. Each of these stages in fuzzy logic modeling of mineral

prospectivity is reviewed below with demonstrations of their applications to epithermal

Au prospectivity mapping in the case study area.

Knowledge-Driven Modeling of Mineral Prospectivity 211

Fuzzification is the processes of converting individual sets of spatial evidence into

fuzzy sets. A fuzzy set is defined as a collection of objects whose grades of membership

in that set range from complete (=1) to incomplete (=0). This contrasts with the classical

set theory, whereby the grade of membership of an object in a set of objects is either

complete (=1) or incomplete (=0), which is applied in the binary representation of

evidence demonstrated above. Thus, in Fig. 7-10, the abstract idea behind the illustration

of fuzzification is to determine the varying degrees of greyness of every pixel in a binary

(or Boolean) image of a grey object.

Fuzzy sets are represented by means of membership grades. If X is a set of object

attributes denoted generically by x, then a fuzzy set A in X is a set of ordered pairs of

object attributes and their grades of membership in A (x, μ

A

(x)):

}))(,{( XxxxA

A

∈μ= (7.3)

where μ

A

(x) is a membership grade function of x in A. A membership grade function,

μ

A

(x), is a classification of the fuzzy membership of x, in the unit interval [0,1], from a

universe of discourse X to fuzzy set A; thus

]1,0[})({ →∈μ Xxx

A

.

In mineral prospectivity mapping, an example of a universe of discourse X is distances to

geological structures. An example of a set of fuzzy evidence from X is a range of

distances to intersections of NNW- and NW-trending faults/fractures (denoted as FI) in

the case study area. Hence, a fuzzy set of ‘favourable distance to FI’ with respect to the

proposition of mineral prospectivity, d, translates into a series of distances (x), each of

which is given fuzzy membership grade, thus:

}))(,{( Xxxxd

d

∈μ= (7.4)

where μ

d

(x) is a mathematical function defining the grade of membership of distance x in

the fuzzy set ‘favourable distance to FI’.

Fig. 7-10. Main stages in fuzzy logic modeling.

212 Chapter 7

For a particular object or value of spatial evidence, the more completely it belongs to

the fuzzy set of favourable evidence, the closer its membership grade is to 1. Thus,

individual objects or values of spatial evidence portrayed in maps can be evaluated in

terms of their membership in a fuzzy set of favourable evidence based on expert

judgment. Grades of membership are usually represented by a mathematical function

that may be linear or continuous; indeed, many fuzzy sets have extremely nonlinear

membership grade functions (Zimmerman, 1991). The evaluation of fuzzy membership

grades always relates to a certain proposition. In mineral prospectivity mapping, the

grade of membership of a class or value of evidence (i.e., geological attributes) in a

fuzzy set of favourable evidence is evaluated according to the proposition “this location

is prospective for mineral deposits of the type sought”.

Fuzzification is thus carried out by application of a membership function μ

A

(x) to a

set or map of values of classes of values of spatial evidence. Robinson (2003) has

reviewed several types of fuzzy membership functions that are applicable to

geographical analysis with the aid of a GIS. In knowledge-driven mineral prospectivity

mapping, the choice or definition of a fuzzy membership function in order to fuzzify a

spatial evidence of mineral prospectivity must be based on sound perception or judgment

of spatial association between geological features represented by the evidence and

occurrence of mineral deposits of the type sought. For example, based on the results of

analysis of spatial association between FI and epithermal Au deposit occurrences in the

case study area (see Table 6-IX), the following membership function may be defined for

the fuzzy set ‘favourable distance to FI’:

°

¯

°

®

>

≤≤

<

−−=μ

4

41

1

0

)14()4(

1

)(

xfor

xfor

xfor

xx

d

(7.5)

where x is distance (km) to FI. The graph and generic form of this function are illustrated

in Fig. 7-11A. The parameters of the function (i.e., 1 and 4, which are α and γ,

respectively, in Fig. 7-11A) are based on (a) range to distances to FI with optimum

positive spatial association with the epithermal Au deposit occurrences, which is 1 km

(see Table 6-IX) and (b) the minimum of the range of distances to FI (e.g., 4 km; see Fig.

6-10B) considered to be completely unfavourable for the occurrence of mineral deposits

of the type sought. The function parameters are chosen arbitrarily based on subjective

judgment or knowledge of spatial association between mineral deposits of interest and

the types of geological features under consideration. The fuzzy membership function in

equation (7.5) or Fig. 7-11A is linear and, thus, inconsistent with the conceptual

knowledge-based representation of spatial evidence illustrated in Fig. 7-8. Alternatively,

the following membership function may be defined for the set ‘favourable distance to

FI’: