Carlip S. Quantum Gravity in 2+1 Dimensions

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

106 6 The

connection representation

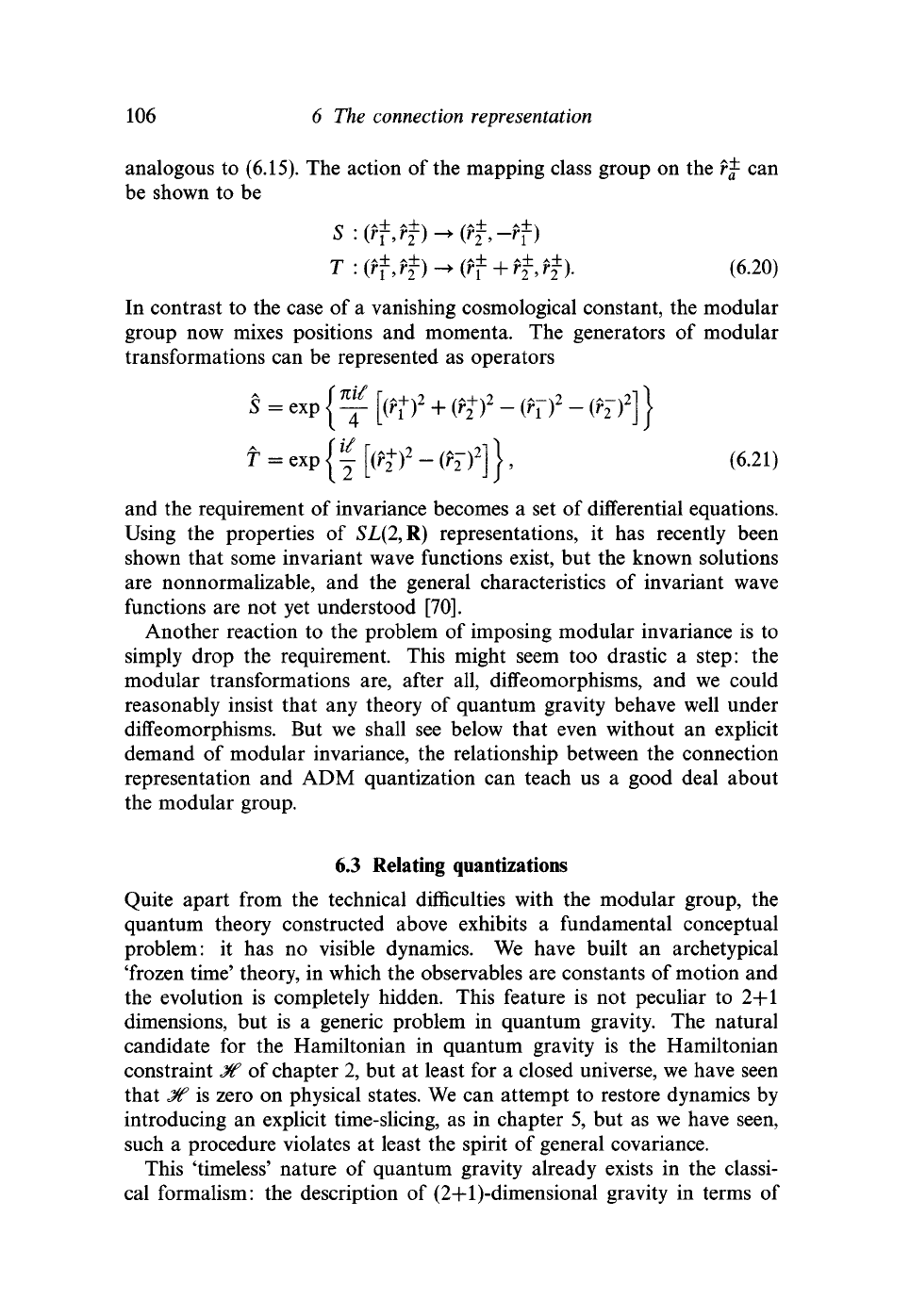

analogous to (6.15). The action of the mapping class group on the rj can

be shown to be

T

:

(^,^)-,(^

+ ^^±). (6.20)

In contrast to the case of a vanishing cosmological constant, the modular

group now mixes positions and momenta. The generators of modular

transformations can be represented as operators

=

exp

{

(ft)

2

+

(ft)

2

~

(K)

2

~

(^]

}

(6.21)

and the requirement of invariance becomes a set of differential equations.

Using the properties of SL(2,R) representations, it has recently been

shown that some invariant wave functions exist, but the known solutions

are nonnormalizable, and the general characteristics of invariant wave

functions are not yet understood [70].

Another reaction to the problem of imposing modular invariance is to

simply drop the requirement. This might seem too drastic a step: the

modular transformations are, after all, diffeomorphisms, and we could

reasonably insist that any theory of quantum gravity behave well under

diffeomorphisms. But we shall see below that even without an explicit

demand of modular invariance, the relationship between the connection

representation and ADM quantization can teach us a good deal about

the modular group.

6.3

Relating quantizations

Quite apart from the technical difficulties with the modular group, the

quantum theory constructed above exhibits a fundamental conceptual

problem: it has no visible dynamics. We have built an archetypical

'frozen time' theory, in which the observables are constants of motion and

the evolution is completely hidden. This feature is not peculiar to 2+1

dimensions, but is a generic problem in quantum gravity. The natural

candidate for the Hamiltonian in quantum gravity is the Hamiltonian

constraint Jf of chapter 2, but at least for a closed universe, we have seen

that Jf is zero on physical states. We can attempt to restore dynamics by

introducing an explicit time-slicing, as in chapter 5, but as we have seen,

such a procedure violates at least the spirit of general covariance.

This 'timeless' nature of quantum gravity already exists in the classi-

cal formalism: the description of (2+l)-dimensional gravity in terms of

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

6.3 Relating quantizations 107

geometric structures exhibits the same lack of explicit dynamics. In the

classical theory, however, this problem causes no great concern. Given a

set of holonomies, we can determine a classical spacetime, and given that

spacetime, we can answer any dynamical question we care to ask: for

example, how do the moduli of a slice of constant TrK evolve with time?

One of the principle achievements of (2+l)-dimensional quantum gravity

has been to show that this procedure can be carried over to a quantum

theory.

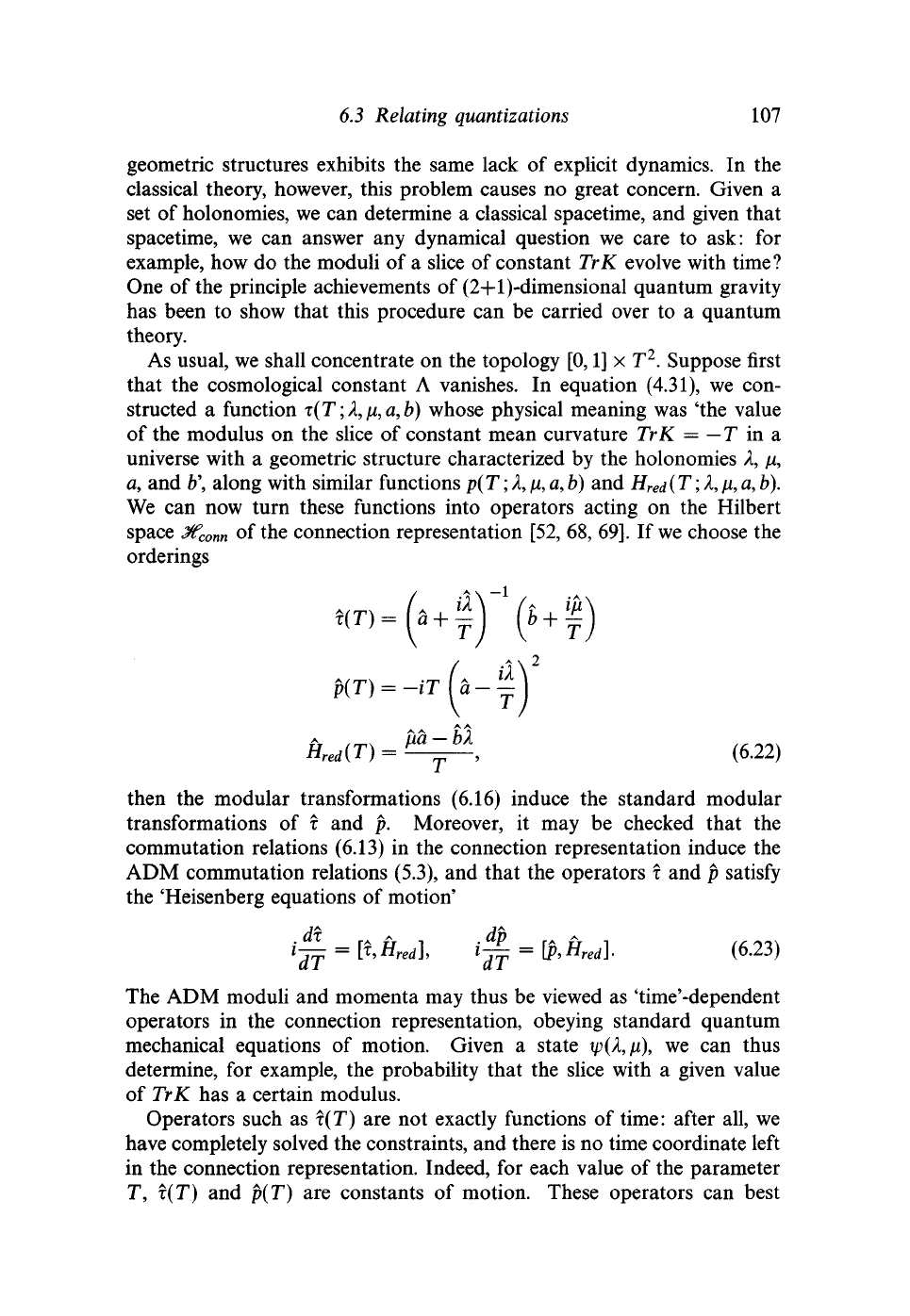

As usual, we shall concentrate on the topology [0,1] x T

2

. Suppose first

that the cosmological constant A vanishes. In equation (4.31), we con-

structed a function T(T;X,fi,a,b) whose physical meaning was 'the value

of the modulus on the slice of constant mean curvature TrK =

—

T in a

universe with a geometric structure characterized by the holonomies A, fi,

a, and b\ along with similar functions

p(T;X,

//,a,b) and H

re

d(T;A,fi,a,b).

We can now turn these functions into operators acting on the Hilbert

space

Jtfconn

of the connection representation [52, 68, 69]. If we choose the

orderings

p(T) = -iT (a -

H

red

(T) = ^, (6.22)

then the modular transformations (6.16) induce the standard modular

transformations of T and p. Moreover, it may be checked that the

commutation relations (6.13) in the connection representation induce the

ADM commutation relations (5.3), and that the operators

T

and p satisfy

the 'Heisenberg equations of motion'

ijf =

[*,

Hred],

^ =

\P,

Hredl (6-23)

The ADM moduli and momenta may thus be viewed as 'time'-dependent

operators in the connection representation, obeying standard quantum

mechanical equations of motion. Given a state tp(A

?)

u), we can thus

determine, for example, the probability that the slice with a given value

of TrK has a certain modulus.

Operators such as T(T) are not exactly functions of time: after all, we

have completely solved the constraints, and there is no time coordinate left

in the connection representation. Indeed, for each value of the parameter

T, T(T) and p(T) are constants of motion. These operators can best

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

108 6 The

connection

representation

be understood as examples of Rovelli's 'evolving constants of motion',

operators that are time-independent but nevertheless provide information

about dynamics [230, 231]. We shall return to the question of how to

interpret such operators at the end of this chapter.

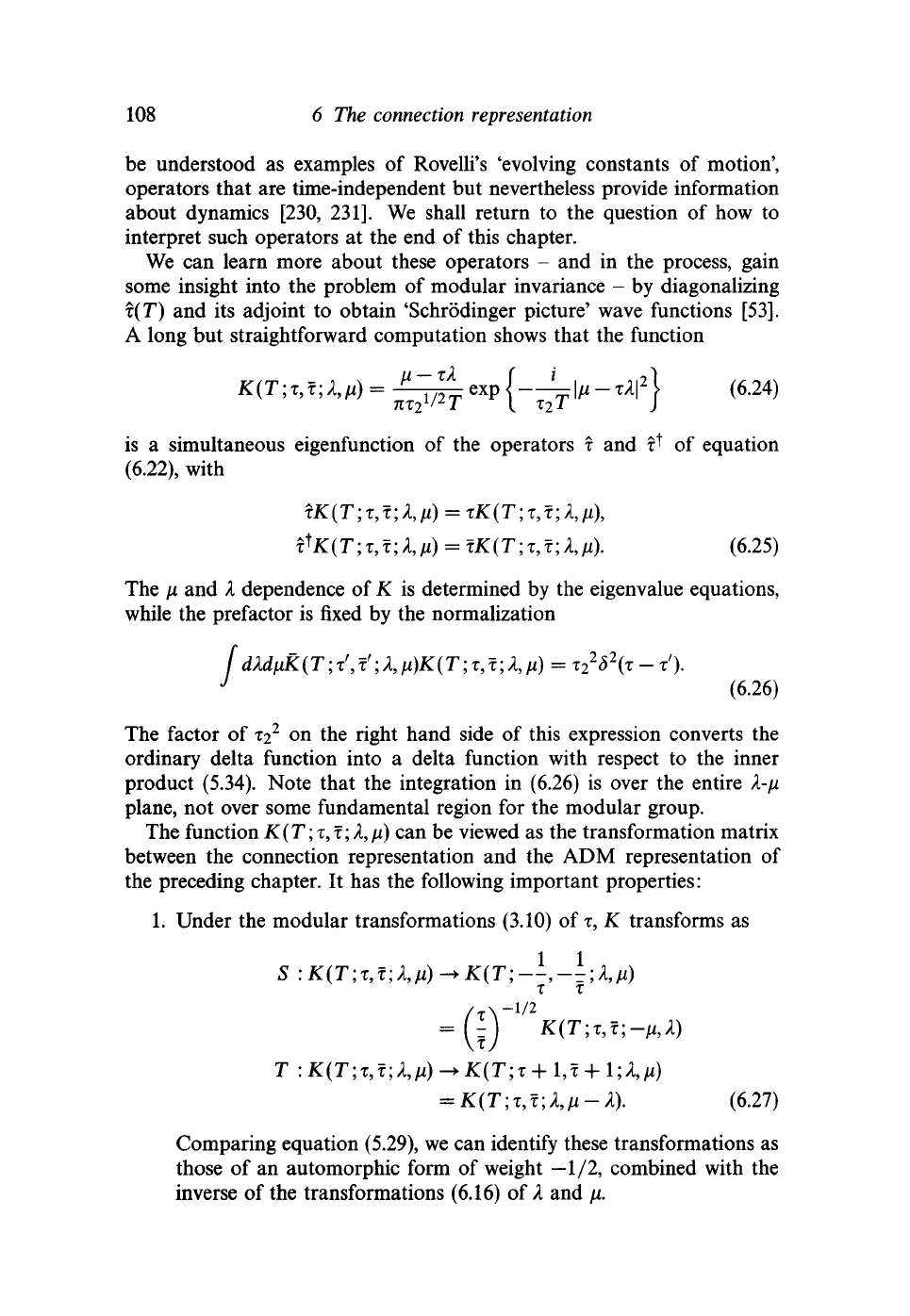

We can learn more about these operators - and in the process, gain

some insight into the problem of modular invariance - by diagonalizing

T(T)

and its adjoint to obtain 'Schrodinger picture' wave functions [53].

A long but straightforward computation shows that the function

(6.24)

is a simultaneous eigenfunction of the operators x and T^ of equation

(6.22),

with

xK(T;x,x;X,n)

= xK{T;x,x;X,n),

^,x;X,n)

= xK{T;x,x\X,n).

(6.25)

The n and

X

dependence of K is determined by the eigenvalue equations,

while the prefactor is fixed by the normalization

(6.26)

The factor of T2

2

on the right hand side of this expression converts the

ordinary delta function into a delta function with respect to the inner

product (5.34). Note that the integration in (6.26) is over the entire l-\i

plane, not over some fundamental region for the modular group.

The function

K(T;T,T;

A,/i)

can be viewed as the transformation matrix

between the connection representation and the ADM representation of

the preceding chapter. It has the following important properties:

1.

Under the modular transformations (3.10) of

T,

K transforms as

1 1

S :

\y

T

:

K(T;T,T;l,ti) -* K(T;T + IT + Ul,fi)

,T;A,/I-A).

(6.27)

Comparing equation (5.29), we can identify these transformations as

those of an automorphic form of weight —1/2, combined with the

inverse of the transformations (6.16) of

X

and \i.

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

6.3

Relating quantizations

109

2.

The connection representation Hamiltonian (6.22) acts on

K as

^,t;X,n).

(6.28)

Moreover, the weight —1/2 ADM Hamiltonian of chapter 5 acts

as

A_

l/2

K(T;x,x;A,

t

i)

=

(iT^=)

K(T;T,T;X,H),

V

dTj

(6.29)

which is the square of the Schrodinger equation (5.37).

We can now write an arbitrary connection representation wave function

A as

a

superposition

d

2

r

K(TVAM%T)

=

(ip

9

K)

9

(6.30)

where property 1 suggests that we should require

xp

to be an automorphic

form

of

weight —1/2. The coefficient

xp,

which we shall interpret

as a

'Schrodinger picture' wave function, has been written as

a

function

of T,

but the

T

dependence is not arbitrary, since the left-hand side of equation

(6.30) is independent

of

T. Indeed, we can use equation (6.26) to solve for

V>(T,T,

T); differentiating with respect

to T

and using (6.29), we find that

If)

^

(T

'

T>T)

=

A

-

which is the square of the Schrodinger equation (5.37) for an automorphic

form of weight —1/2.

To determine the region

of

integration

& in

(6.30),

let

us consider the

normalization of wave functions:

<VlV>

=

(6.32)

r

r

d

2

r

d

2

r

f

>

dMfi

/

_-^K(T;T,T;A^)K(T;T

/

,T

/

;A,

i

u)v(T,T,T)^(T

/

,T

/

,T)

d

2

r

d

2

r

f

_ C d

2

r

—

^r

T

2

2

^(t-T0^,T,T)^(T

/

,f

/

,T)= / _|tp(

T

,T,r)|

2

,

where

I

have used

the

orthogonality relations (6.26)

for K. But

xp

is

an automorphic form,

so

this last integral will

be

normalized

if & is a

fundamental region for action of the modular group on Teichmiiller space,

such as the 'keyhole region' described

in

appendix A.

We can now return

to

the question

of

how the modular group acts

in

the connection representation. A wave function defined by equation (6.30)

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

110 6 The connection representation

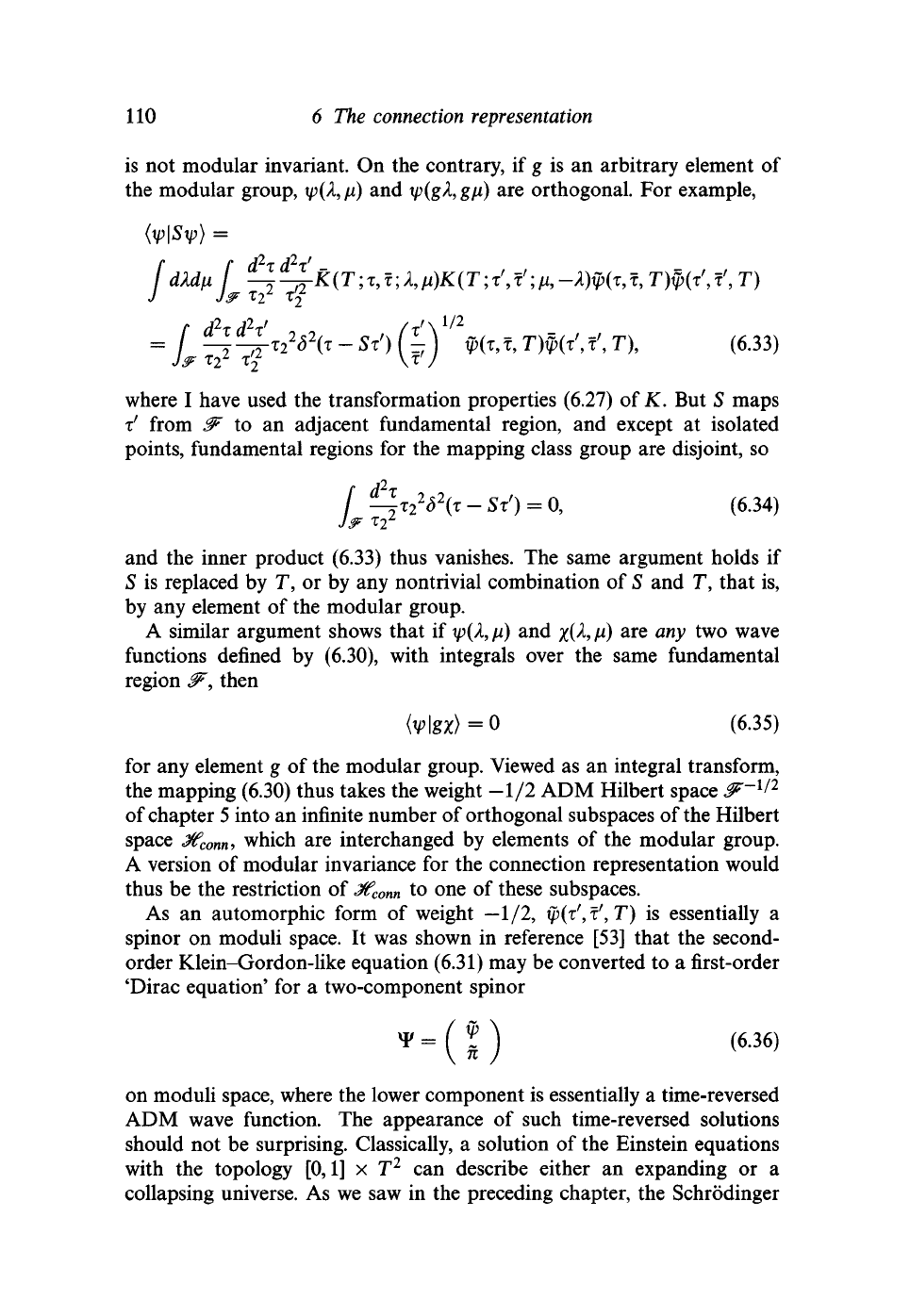

is not modular invariant. On the contrary, if g is an arbitrary element of

the modular group, tp(/l,/x) and ip(ghgfi) are orthogonal. For example,

(xp\Sxp)

=

r r d

2

r dV -

/T'X

1

/

2

,T',

T\ (6.33)

d

2

x

d

2

x

r

- Sx') -

\T'J

where I have used the transformation properties (6.27) of K. But S maps

x

1

from IF to an adjacent fundamental region, and except at isolated

points, fundamental regions for the mapping class group are disjoint, so

- Sx') = 0, (6.34)

and the inner product (6.33) thus vanishes. The same argument holds if

S is replaced by T, or by any nontrivial combination of S and T, that is,

by any element of the modular group.

A similar argument shows that if y(A,/i) and x(/l,ju) are any two wave

functions defined by (6.30), with integrals over the same fundamental

region J% then

(vl?z)=0 (6.35)

for any element g of the modular group. Viewed as an integral transform,

the mapping (6.30) thus takes the weight —1/2 ADM Hilbert space #'~

1

/

2

of chapter

5

into an infinite number of orthogonal subspaces of

the

Hilbert

space

J^conn,

which are interchanged by elements of the modular group.

A version of modular invariance for the connection representation would

thus be the restriction of

J^

con

n

to one of these subspaces.

As an automorphic form of weight —1/2, ip(x\x

f

, T) is essentially a

spinor on moduli space. It was shown in reference [53] that the second-

order Klein-Gordon-like equation (6.31) may be converted to a first-order

'Dirac equation' for a two-component spinor

| ) (6-36)

on moduli space, where the lower component is essentially a time-reversed

ADM wave function. The appearance of such time-reversed solutions

should not be surprising. Classically, a solution of the Einstein equations

with the topology [0,1] x T

2

can describe either an expanding or a

collapsing universe. As we saw in the preceding chapter, the Schrodinger

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

6.3 Relating

quantizations

111

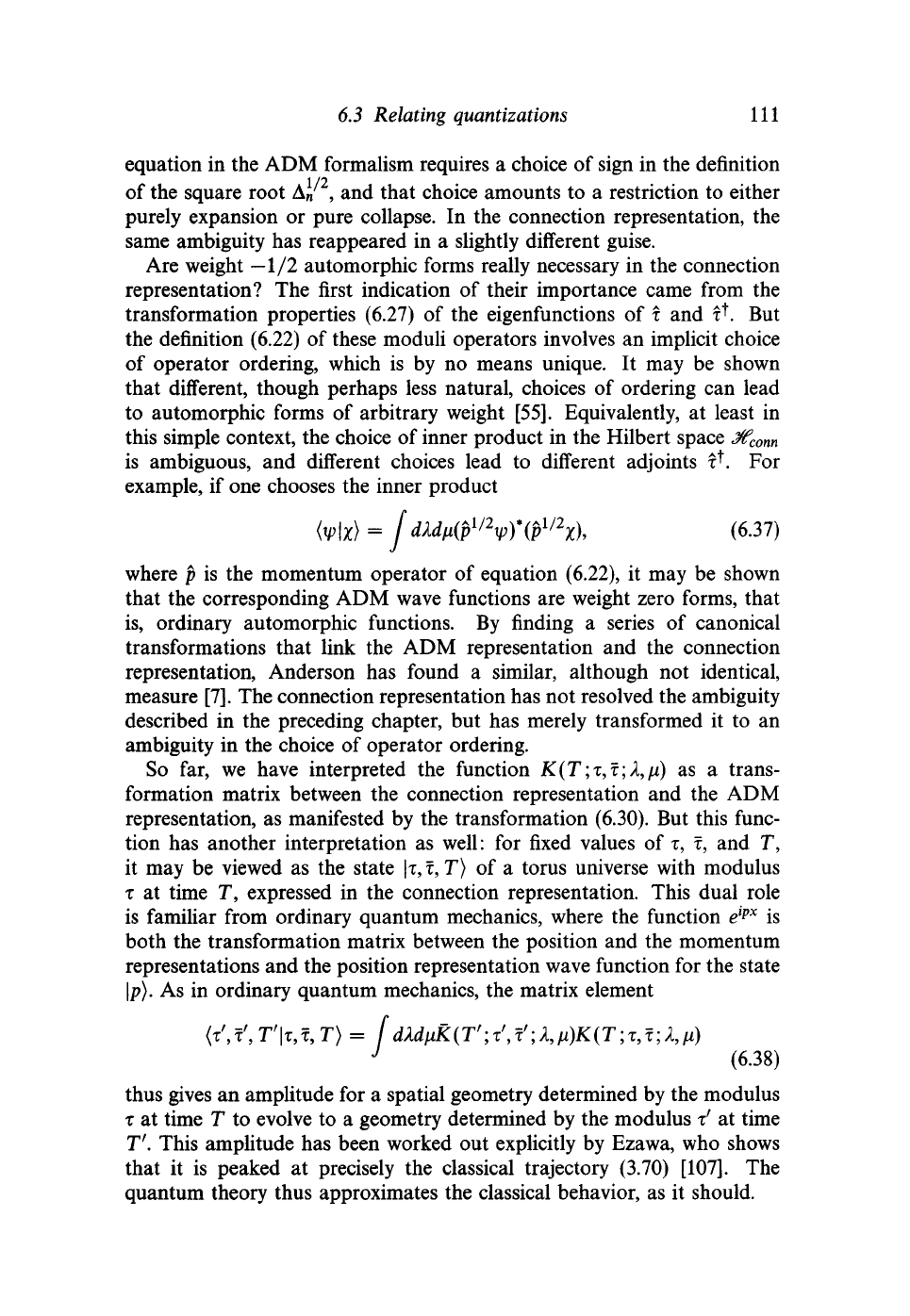

equation in the ADM formalism requires

a

choice

of

sign in the definition

of the square root A

n

,

and that choice amounts

to a

restriction

to

either

purely expansion

or

pure collapse.

In

the connection representation,

the

same ambiguity has reappeared

in a

slightly different guise.

Are weight —1/2 automorphic forms really necessary

in

the connection

representation?

The

first indication

of

their importance came from

the

transformation properties (6.27)

of

the eigenfunctions

of

T

and

T^.

But

the definition (6.22)

of

these moduli operators involves

an

implicit choice

of operator ordering, which

is by no

means unique.

It

may

be

shown

that different, though perhaps less natural, choices

of

ordering can lead

to automorphic forms

of

arbitrary weight [55]. Equivalently,

at

least

in

this simple context, the choice of inner product in the Hilbert space

J^

C

onn

is ambiguous,

and

different choices lead

to

different adjoints

ft". For

example,

if

one chooses the inner product

{y>\x)

=

J

dMi4P

l/2

V>T(P

l/2

X),

(6-37)

where

p is

the momentum operator

of

equation (6.22),

it

may

be

shown

that the corresponding ADM wave functions are weight zero forms, that

is,

ordinary automorphic functions.

By

finding

a

series

of

canonical

transformations that link

the

ADM representation

and the

connection

representation, Anderson

has

found

a

similar, although

not

identical,

measure [7]. The connection representation has not resolved the ambiguity

described

in the

preceding chapter,

but

has merely transformed

it to an

ambiguity

in

the choice

of

operator ordering.

So

far, we

have interpreted

the

function

K(T;T,T;A,ii)

as a

trans-

formation matrix between

the

connection representation

and the

ADM

representation, as manifested by the transformation (6.30). But this func-

tion

has

another interpretation

as

well:

for

fixed values

of

T,

T,

and T,

it may

be

viewed

as the

state

|T,T,

T) of a

torus universe with modulus

T

at

time

T,

expressed

in the

connection representation. This dual role

is familiar from ordinary quantum mechanics, where

the

function

e

ipx

is

both the transformation matrix between the position and the momentum

representations and the position representation wave function for the state

\p).

As

in

ordinary quantum mechanics, the matrix element

(T',T',T'|T,T,:T)

= \

J

(6.38)

thus gives an amplitude for

a

spatial geometry determined by the modulus

T

at

time

T

to evolve

to a

geometry determined by the modulus

x

1

at

time

V.

This amplitude has been worked out explicitly by Ezawa, who shows

that

it is

peaked

at

precisely

the

classical trajectory (3.70)

[107].

The

quantum theory thus approximates the classical behavior, as

it

should.

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

112 6 The connection representation

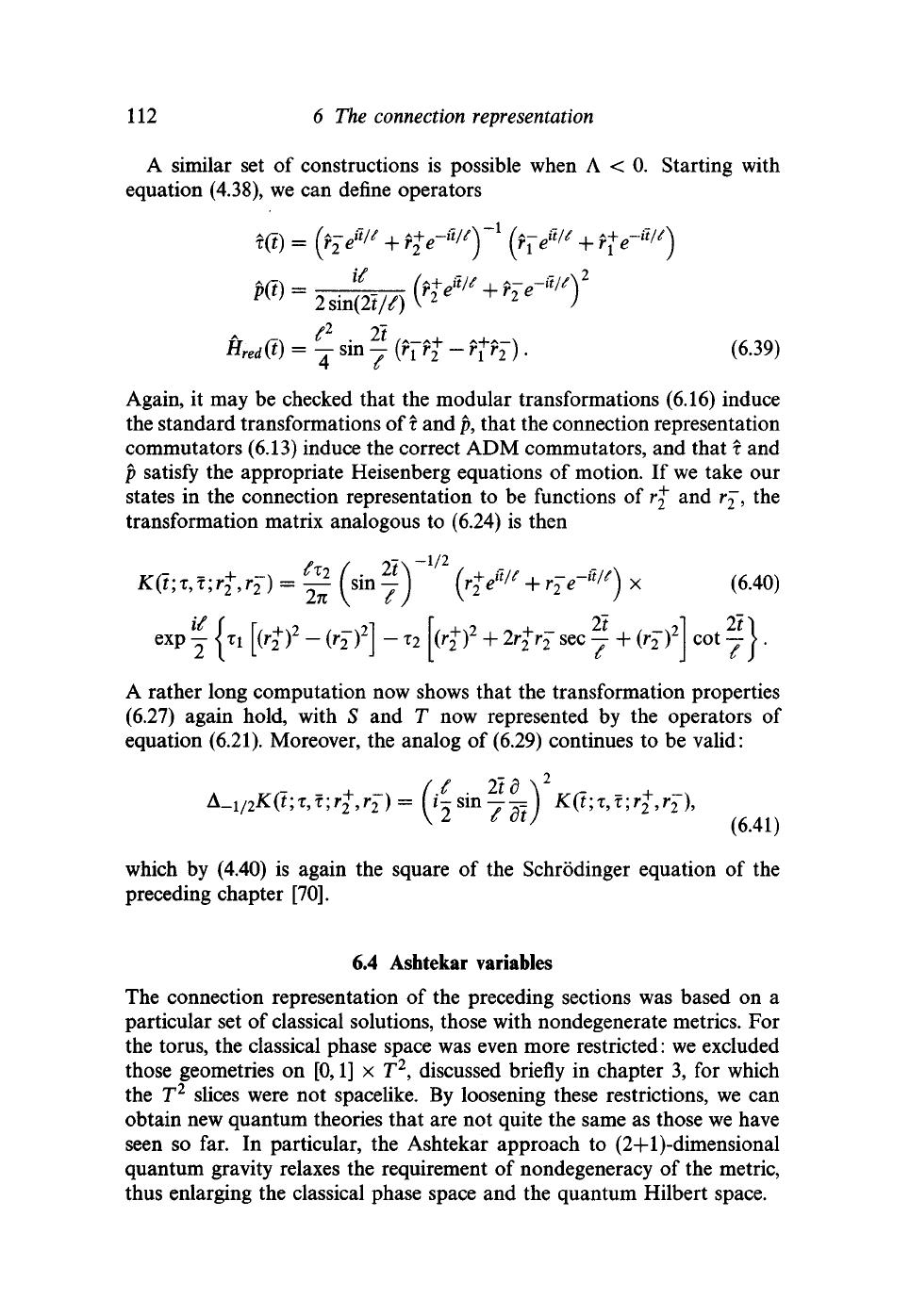

A similar set of constructions is possible when A < 0. Starting with

equation (4.38), we can define operators

-l

KdCt) = j sin | (fftf - Pfo-). (6.39)

Again, it may be checked that the modular transformations (6.16) induce

the standard transformations oft and

p,

that the connection representation

commutators (6.13) induce the correct ADM commutators, and that

T

and

p satisfy the appropriate Heisenberg equations of motion. If we take our

states in the connection representation to be functions of rj and r^~, the

transformation matrix analogous to (6.24) is then

K(7;t,t;r

2

+

,r

2

-) = g (sin

j^'^

{$*"

+

r^e"*") x (6.40)

exp

f

{t! [(r+)

2

-

(r

2

-)

2

]

-1

2

[(r

2

+)

2

+

2r

2

+

r

2

-

sec

|

+

(r

2

~)

2

]

cot |} .

A rather long computation now shows that the transformation properties

(6.27) again hold, with S and T now represented by the operators of

equation (6.21). Moreover, the analog of (6.29) continues to be valid:

=

(i-sin—-=)

l € dtj

(641)

which by (4.40) is again the square of the Schrodinger equation of the

preceding chapter [70].

6.4 Ashtekar variables

The connection representation of the preceding sections was based on a

particular set of classical solutions, those with nondegenerate metrics. For

the torus, the classical phase space was even more restricted: we excluded

those geometries on [0,1] x T

2

, discussed briefly in chapter 3, for which

the T

2

slices were not spacelike. By loosening these restrictions, we can

obtain new quantum theories that are not quite the same as those we have

seen so far. In particular, the Ashtekar approach to (2+l)-dimensional

quantum gravity relaxes the requirement of nondegeneracy of the metric,

thus enlarging the classical phase space and the quantum Hilbert space.

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

6.4 Ashtekar variables 113

In the connection representation developed in the last two sections, the

phase space T* Jf was a space of flat metrics and spin connections. This

flatness originates in the constraints of chapter 2,

=

\&

\d

iej

a

-

djef

+

e

abc

(co

ib

e

jc

-

co

jb

e

ic

)]

= 0,

2

(6

(6.42)

,*]

= ^Fij = y>

[dicoj

a

-

djCOi

a

+

e

abc

co

ib

co

jc

]

= 0, (6.43)

where D\ denotes the

SO (2,1)

gauge-covariant derivative. The Ashtekar

constraints, on the other hand, take a slightly different form. The phase

space variables are again a spin connection and a triad, or more commonly

a spin connection and a densitized triad,*

E

ia

= e

ij

ej

a

, (6.44)

which clearly carries exactly the same information as e. The constraints

are now written in a form identical to that of the Ashtekar constraints in

3+1 dimensions [11, 35],

D

t

E

ia

= 0,

(6.45)

E'aFfj

= 0,

(6.46)

e

abc

E

ib

EJ

c

F?j

= 0. (6.47)

The constraint (6.45) is clearly equivalent to (6.42). When the spatial

metric gtj =

e\

a

ej

a

is nondegenerate, it is not hard to show that the con-

straints (6.46)-(6.47) are equivalent to (6.43). Indeed, using the definition

of E

ia

and the fact that Ff

}

=

e\f£

a

>

we can rewrite these constraints as

eutf"

= 0

€abce

kl

e

k

b

ei

c

^

a

= 0

(6.48)

and the equivalence follows from some elementary algebra.

The Ashtekar constraints (6.45)-(6.47) admit additional solutions, how-

ever, for which the spatial metric is degenerate and the curvature Ffj does

not vanish. The full space of solutions is not completely understood, but

portions have been investigated. Barbero and Varadarajan have argued

that the full phase space has an infinite number of degrees of freedom

[25].

Let us define a 'flat patch' of a surface Z as a region in which the

constraints (6.42)-(6.43) are satisfied, and a 'null patch' as a region in

which the metric is degenerate, the constraints (6.45)-(6.47) are satisfied,

*

It is

traditional

in

papers using Ashtekar variables

to use a

tilde over

a

letter

to

denote

a density

of

weight

one.

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

114 6 The

connection representation

and curvature satisfies

<€

a

<€

a

= 0. Then if initial data are chosen so that Z

consists of a collection of disjoint flat patches separated by null patches,

this pattern is preserved by evolution, and the holonomies in each of the

flat patches become independent observables. The consequences for the

quantum theory are not yet understood, although some work has been

done in the loop representation and in minisuperspace models [26, 109].

At a minimum, the (2+l)-dimensional model serves as a warning that

the choice of how to treat degenerate metrics in quantum gravity can

drastically affect the outcome.

6.5 More pros and cons

The quantum theory developed in this chapter has managed to avoid

some of the conceptual difficulties of the reduced phase space ADM

quantization of chapter 5. In particular, we have not had to choose any

particular time slicing, and have thus preserved general covariance. This

manifest covariance comes at a price: the physical interpretation of the

resulting 'frozen time' formalism, and in particular the identification of

dynamical behavior, becomes much less obvious. But we have seen in at

least one example that the problems of interpretation can be overcome,

and that dynamical questions can be answered through the construction

of appropriate operators.

Operators of the sort we have studied here are not quite 'dynamical'.

The modulus

T(T),

for example, should not be thought of as a single,

time-dependent operator. Rather, for each value of the parameter T,

T(T)

is defined throughout spacetime, and commutes with the constraints - it

is a constant of motion, or in Kuchaf's terms, a 'perennial'

[172].

We

must interpret

T(T)

as a one-parameter family of operators, indexed by a

number T, that are defined everywhere.

Nevertheless, we can use the correspondence principle and our knowl-

edge of the classical theory to give

T(T)

its dynamical interpretation as

the operator that represents the modulus of the slice TrK = — T. The

rather mysterious role of time may become clearer when we compare the

quantum theory to the classical theory of chapter 4. There, too, the space-

time geometry was described completely in terms of constants of motion,

and no explicit time coordinate was ever introduced. Cosgrove has called

the resulting quantum theory 'quantization after evolution': the dynamics

is completely solved classically and reexpressed in terms of correlations

among time-independent constants of motion, which can then be studied

quantum mechanically [81]. This point of view is closely related to Rov-

elli's description of quantum mechanics in terms of 'evolving constants of

motion' [230, 231].

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009

6.5 More pros and cons 115

We can now return to a question raised in the preceding chapter:

are the quantum theories corresponding to different choices of time-

slicing equivalent? In this chapter, we considered only a particular set

of 'dynamical' operators, those corresponding to the York time-slicing

TrK = — T. But nothing prevents us from looking at a different choice

of slicing. Given any classical choice of time, with slices labeled by some

parameter t, we can construct the corresponding classical observables x(t)

and p(t) and convert them into operators in the connection representation.

Just as we did for the York slicing, we can then diagonalize x(t) and its

adjoint and transform to a 'Schrodinger picture'.

By construction, though, this 'Schrodinger picture' is equivalent to

the original 'Heisenberg picture' of the connection representation. In

particular, a transition amplitude between slices t\ and tf depends only

on the initial operator

T(U)

and its adjoint, the final operator x(tf) and its

adjoint, and a time-independent wave function

\p(X,ix).

Provided that the

operator orderings in

T(£,-), %tf\ and their adjoints are fixed, the choice of

intermediate slicing cannot affect the amplitude.

This last proviso, however, emphasizes a remaining arbitrariness in the

connection representation. Dynamical quantities like

T(T)

are classically

well-determined, but the process of constructing operators is fraught with

ordering ambiguities. In particular, the 'natural' ordering with respect

to one choice of time-slicing may not be the same as the 'natural' or-

dering with respect to another. This problem reflects a genuine physical

uncertainty: when we measure a classical gravitational field, we do not

know exactly which quantum operators we are observing. This problem

is already present in ordinary quantum mechanics, although it is usually

ignored because we 'know' the right variables. But we know only because

of the results of experiments, and these are sorely lacking in quantum

gravity.

A similar ambiguity arises in the choice of polarization, that is, the

splitting of the phase space into 'positions' and 'momenta'. We saw briefly

in section 2 that this choice can, at a minimum, affect the representation of

the modular group. There is no proof that different choices of polarization

lead to equivalent quantum theories, and there is no obvious way to choose

a 'correct' polarization, although the mapping class group might offer some

guidance.

There is another difficulty with the connection representation, which is in

some sense 'merely technical' but which has the potential to cause serious

problems. To construct the dynamical operators needed for a physical

interpretation, we must know the classical solutions of the equations of

motion; more specifically, we need a parametrization of the classical

solutions in terms of a set of constants of motion. Equation (6.22) for

the operator T, for example, was obtained from the classical equation

Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2009