Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS: STRUCTURAL ISSUES 421

Coordination and control mechanisms

The terms ‘control’ and ‘coordination’ are often used without it being clear whether there

is any difference between them. Control can be defined as ‘the regulation of activities

within an organization so that they are in accord with the expectations established in poli-

cies and targets’ (Child, 1973: 117). Coordination is ‘an enabling process to bring about

the appropriate linkages between tasks’ (Cray, 1984: 86). Both control and coordination

pertain to the direction of efforts towards organizational goals. The concept of ‘control’

suggests a power difference that is not implicit in that of ‘coordination’ (Harzing, 1999:

9). However, as the two concepts are strongly related, and as coordination/control mech-

anisms based on power differentials and on other bases in practice coincide, we will use

the terms interchangeably.

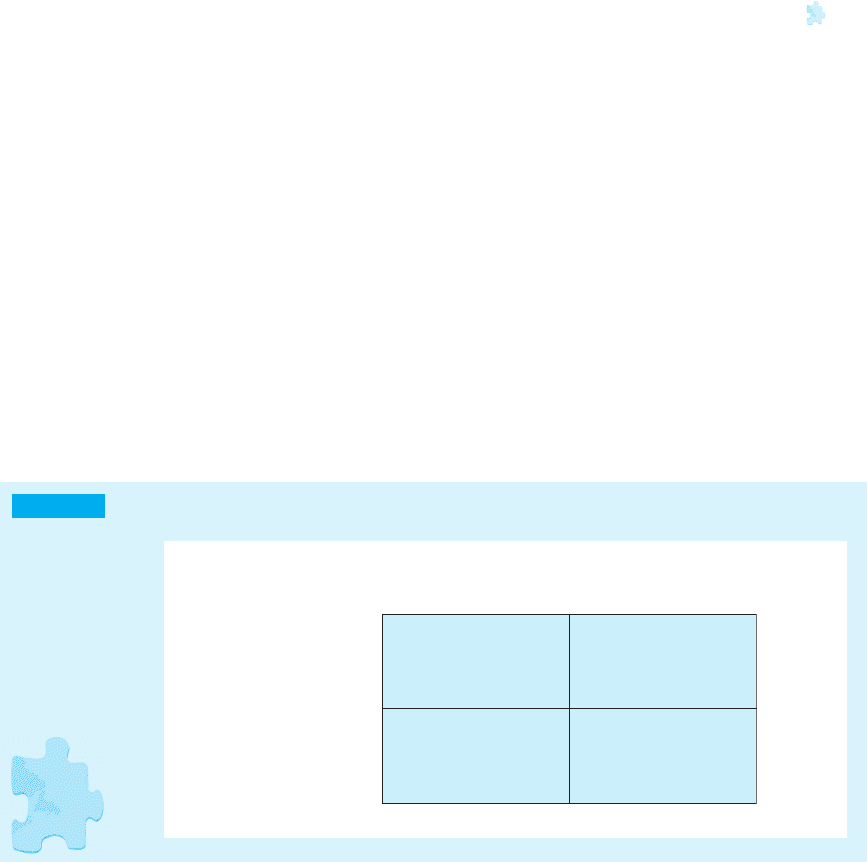

Synthesizing the literature on control mechanisms, Harzing (1999: 21) distinguishes

between direct and indirect mechanisms on the one hand, and personal and impersonal

mechanisms on the other. On this basis, she categorizes control mechanisms into four

groups (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Four categories of coordination and control mechanism

Personal centralized

control

Output control

Bureaucratic formalized

control

Indirect/implicit

Direct/explicit

Control by socialization

and networks

Personal/cultural

(founded on social

interaction)

Impersonal/bureaucratic

(founded on instrumental

artefacts)

Source: Harzing (1999: 21).

Personal centralized control is based on the organizational hierarchy, and works

through supervision and intervention by managers. Bureaucratic formalized control con-

sists of the formulation of rules, procedures and standards for the work activities to be

performed in the organization. Output control, in contrast, does not specify work pro-

cedures, but plans targets for the organizational units, while these units have a large

degree of freedom in deciding how to reach these targets. Control by socialization and net-

works, finally, is a mixed bag of coordination activities that have as a common

characteristic that they are neither hierarchical nor bureaucratic. Mechanisms that

belong to this category are the socialization of managers and employees, the informal

exchange of information (i.e., not as part of formalized control or reporting procedures),

and the formalized lateral relationships between organizational units (but not based on

hierarchy, unlike in the case of personal centralized control).

The extent to which these various types of control mechanism are used by MNCs

depends on many factors. An important factor is size. Large organizations can rely only to

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 421

a limited extent on personal centralized control, otherwise the number of managers

would be too large and there would be too many layers in the hierarchy. Hence, these large

MNCs tend to have a relatively strong emphasis on bureaucratic formalized control.

Another factor is the organizational macro structure, discussed earlier in this chapter. The

macro structure can be seen as a schematic rendering of the most important formal auth-

ority relations within the MNC. Hence, the structure shows who reports to whom at the

top of the MNC, both in the sense of personal supervision and of bureaucratic control.

Furthermore, we can assume that in the multidomestic form, the control mechanism

used in the relationship between the corporate headquarters and the division will be pre-

dominantly of the output control type. Bureaucratic formalized control or personal

centralized control would make little sense, as headquarters does not want to interfere in

the day-to-day operations of the local subsidiaries. However, the organizational macro

structure as such gives little clues as to the mix of control mechanisms used to realize

coordination in the organization as a whole (i.e. below the top management level). An

exception is the matrix structure. International matrix-like structures are indicated as the

structure of choice in situations of high foreign-product diversity and high foreign sales

(Stopford and Wells, 1972, or in situations where there are strong pressures to localize and

strong forces to integrate across borders (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 2000). In this type of situ-

ation, and with this kind of macro structure, a strong emphasis on more informal control

mechanisms, in particular socialization and networks, is to be expected.

Just as the organizational structure of the MNC can never be based on a single crite-

rion (e.g. product categories or geographical regions), no MNC can achieve the necessary

internal coordination with just a single coordination mechanism. The mechanisms

should be seen as complements, rather than substitutes (Harzing, 1999: 23). In reality

there will always be a mix of control mechanisms, but the balance between the various

mechanisms used differs between MNCs and within MNCs at different hierarchical levels.

Even at one particular level, different control mechanisms may dominate in different

places. For instance, in the relationship between headquarters and some subsidiaries,

output control may dominate, while in other subsidiaries a much more direct supervision

of the personal centralized type is exerted. This is likely to depend on the roles of the sub-

sidiaries in question within the MNC, a subject we will discuss later in this chapter.

There are several reasons to expect that it is more difficult for an MNC to exert control

and realize coordination of its activities than for a firm operating within a single country.

Daniels and Radebaugh (2001: 518) note that four factors cause these greater difficulties,

compared to single-country firms:

1. the greater geographical and cultural distance between units of the MNC

2. the greater diversity in the environments (in terms of market conditions, standards,

currencies, etc.) in which the MNC works

3. factors that limit the control of MNC headquarters over all the activities of the firm,

such as local stockholders, local government regulations, and so on

4. the higher degree of uncertainty (e.g. because of a lack of accurate and timely data).

As a result, in the context of the MNC the various control mechanisms meet with a

number of specific difficulties. Personal centralized control is made more difficult because

local managers may give little support to headquarters interventions, which may easily be

422 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 422

seen as ignoring local circumstances and developments. Likewise, bureaucratic formal-

ized control, because of its standardized nature, will often ignore the heterogeneity of the

countries in which the MNC operates. The effectiveness of output control is restricted

because the limited information flow from subsidiaries to headquarters gives unscrupu-

lous subsidiary managers opportunities for manipulation. Working with socialization and

networks is more difficult in MNCs because, for these mechanisms, frequent face-to-face

contacts and interactions are essential. Moving around staff in expatriate positions can be

a way to promote socialization and the formation of a common organizational culture

(although it can also be part of a strategy of centralized personal supervision). However,

because of the high cost, the use of this mechanism between headquarters and sub-

sidiaries, as well as among subsidiaries, can only be limited.

Over time, and in conjunction with changing organizational macro structures, MNCs

have started to use a more diverse mix of control mechanisms. Centralized personal

control, partly through the use of expatriates, was the dominant coordination mech-

anism for multidomestic MNCs in the period 1920–50 (this and the following is based on

Martinez and Jarillo, 1989). On top of this, output control (mainly financial performance)

was used. Global MNCs (most prominent from 1950–80) relied more heavily on bureau-

cratic formalized control in the form of formal planning and budgeting systems. Martinez

and Jarillo (1989) observe that these bureaucratic controls were complemented by output

control in US MNCs, but more by cultural control (among other things, through the use

of expatriates) in Japanese MNCs. As the pressures towards both local adaptation and

global integration increased (from 1980), and MNCs moved towards the transnational

form, more and more emphasis has been put on the informal control mechanisms

belonging to Harzing’s (1999) category of socialization and network control. The use of

these mechanisms is, however, cumulative: they are used on top of the three other cat-

egories of control mechanism. Hence we can say that from the point of view of

organizational control MNCs tending towards Bartlett and Ghoshal’s ‘transnational’ type

are very complex organizations.

Headquarters–subsidiary relationships

Christopher Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal (1989) make the point that responding sim-

ultaneously to pressures of local adaptation and global integration requires more than

just a structural solution. More subtle forms of control and organization – like those dis-

cussed above under the heading of ‘socialization and networks’ – are also necessary. Most

of all, these authors called for a new mentality, which was seen as necessary in order to

achieve the flexibility required. This new mentality not only pertains to the macro struc-

ture and the mix of coordination mechanisms used, but also more in general to the

relationship between headquarters and subsidiaries.

Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986) observe two dysfunctional ‘syndromes’ in head-

quarters–subsidiary relationships in MNCs. The ‘UN model’ syndrome implies that MNC

headquarters’ relationships with subsidiaries are based on the assumption that these

should be treated in a uniform manner. Subsidiary roles and responsibilities are expressed

in the same general terms, planning and control systems are applied uniformly and all

subsidiaries typically enjoy the same degree of autonomy. The ‘headquarters hierarchy’

syndrome points at the tendency in many MNC headquarters to keep all key decisions

MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS: STRUCTURAL ISSUES 423

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 423

424 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

centralized. The two syndromes are related: because headquarters have the tendency to

treat all subsidiaries in the same way, all subsidiaries receive the same low degree of

autonomy and play the same restricted role within the MNC (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1986:

88). By treating their subsidiaries in this uniform way, MNCs deny the possibility that sub-

sidiaries develop in different directions and acquire new capabilities that enable them to

play a lead role within their area of competence. The existence of multiple subsidiary roles

is one of the essential characteristics of the transnational form.

Building on Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986) and a number of empirical studies,

Birkinshaw and Morrison (1995) distinguish between three subsidiary roles (see Table

9.1). Local implementers typically operate within a single country. The main responsibility

of this type of subsidiary is to adapt global products to the needs of the local market.

Within that local market the subsidiary operates with a certain level of autonomy.

Specialized contributors have considerable expertise, but in a narrowly defined area. Their

activities are strongly intertwined with those of other units of the MNC; hence their

autonomy is limited. Subsidiaries with a world mandate, finally, have a worldwide (or at

least region-wide) responsibility for a product line or certain types of value-adding

activity. Thus there is worldwide integration, but the activities are coordinated not by

headquarters, but from the subsidiary.

In Table 9.1, a number of dimensions in which the three types of subsidiary differ are

indicated. The world mandate subsidiary has the largest strategic autonomy, the local

implementer the smallest (all three types score equally in operational autonomy). The

‘product dependence on the parent’ dimension reflects the extent to which the products of

the subsidiary are also produced by the parent company. The assumption is that, if this is

the case, the subsidiary is more dependent on the parent with regard to these production

Source: adapted from Birkinshaw and Morrison (1995: 748).

Table 9.1 Roles of MNC subsidiaries

Local

implementer

Specialized

contributor

World mandate

subsidiary

Strategic autonomy low medium high

Product dependence

on the parent

high high low

Inter-affiliate

purchases

high high low

International

dispersion of

manufacturing

low high medium

International

dispersion of

downstream

activities

low high medium

Pressures for

national

responsiveness

high medium low

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 424

activities. This dependency is lower for world mandate subsidiaries than for the two other

types. Inter-affiliate purchases are products or components that the subsidiary buys from

other parts of the MNC. Local implementers and specialized contributors are strongly

bound to the MNC by such material flows, world mandate subsidiaries more weakly.

International dispersion of manufacturing and of downstream activities shows to what

extent the activities performed by the subsidiary also take place at other locations within

the MNC. The activities of local implementers tend to be specific to their location, and

hence are not replicated elsewhere in the MNC. The activities of specialized contributors

are more strongly linked to like operations elsewhere in the world; world mandate sub-

sidiaries fall between these two types in this respect.

If we tentatively link the three subsidiary roles with the MNC typology of Bartlett and

Ghoshal, a first remark should be that each of the three kinds of subsidiary could be

assumed to exist within each of the four types of MNC. However, the description of the

subsidiary roles suggests that the local implementer may be assumed to be particularly

prominent in international MNCs and multidomestic MNCs. Within the second type of

MNC the local implementer will have more autonomy than within the first. The special-

ized contributor is more likely to be found in the global MNC. The world mandate

subsidiary, finally, fits best with the transnational MNC. In this type of MNC the idea that

different capabilities may be concentrated in different subsidiaries, and that, conse-

quently, some subsidiaries (rather than headquarters) should have central authority in

some fields, is most likely to be accepted.

Birkinshaw and Morrison (1995), in their study, also checked for the need for global

integration and the need for local responsiveness, as perceived by the subsidiaries. While

there were no significant differences between the three subsidiary types regarding the per-

ceived need for global integration, local implementers expressed a significantly higher

need for local adaptation than world mandate subsidiaries. Specialized contributors fall in

between. The link between the management of headquarters–subsidiary relationships

and the environment was further explored in a study of 618 headquarters–subsidiary

relationships by Ghoshal and Nohria (1989). These authors linked parameters describing

the degree of centralization, formalization and socialization (comparable with Harzing’s

personalized supervision, formalized bureaucratic and socialization network control

types, respectively) in these relationships to the complexity/stability of the environment

and the local resources commanded by the subsidiaries. In their relationships with sub-

sidiaries operating in complex environments and commanding abundant local resources,

MNC headquarters rely relatively little on centralization of authority, and relatively much

on formal control and socialization. Centralization is lowest when local resources are

abundant, but the local environment is stable. These subsidiaries are left to look after

themselves, one might say. If the environmental complexity is high but local resources are

limited, centralization is intermediate and formalization is low. The picture with regard to

subsidiaries with limited local resources and operating in a stable environment was less

clear, in that no statistically significant differences between these subsidiaries and any of

the other group were found. Although not directly comparable to the study of Birkinshaw

and Morrison (1995), these results suggest that important environmental variables influ-

ence the headquarters–subsidiary relationship.

In a later study, Ghoshal and Nohria (1993) focused on the differentiation of sub-

sidiary roles within MNCs. They looked at the pressures to localize and those to globally

MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS: STRUCTURAL ISSUES 425

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 425

426 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

integrate in the environment of the MNC, and at the internal integration and differentia-

tion in headquarters–subsidiary relationships. A high internal integration means that the

MNC intensively uses authority hierarchies, formalized bureaucratic systems and/or

socialization mechanisms to achieve a high degree of coordination across its different

units. The differentiation dimension pertains to the question of whether the mix of

coordination mechanisms used and/or their intensity differs between subsidiaries, or that

MNC headquarters manages all subsidiaries in a uniform way. Putting these two dimen-

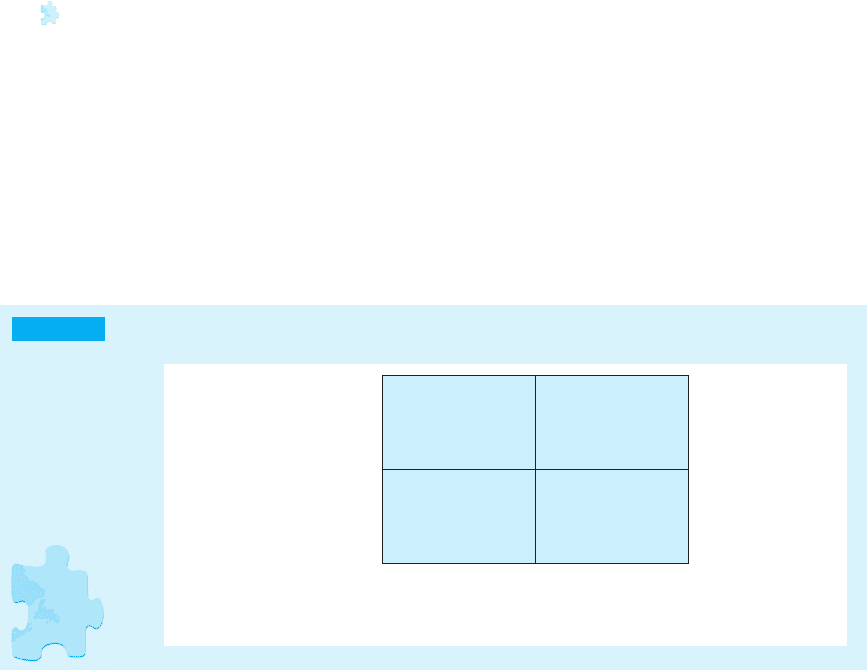

sions together, Ghoshal and Nohria (1993) specify four patterns of the overall structuring

of headquarters–subsidiary relationships (see Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5 Patterns of structuring of headquarters–subsidiary relationships

Structural

uniformity

Differentiated

fit

Integrated

variety

Low High

Structural integration

Ad hoc

variation

Low High

Structural differentiation

Source: Ghoshal and Nohria (1993: 31).

Structural uniformity is the pattern in which the structural integration (through hier-

archy, bureaucratic means and/or socialization) is strong and uniform throughout the

MNC. There is one ‘company way’ of managing subsidiary relationships. In the differenti-

ated fit variety, different coordination mechanisms are used for different subsidiaries. This

is also true for the pattern of integrated variety, but in this case the MNC overlays one domi-

nant integrative mechanism (which may be of a hierarchical, bureaucratic or socializing

kind) for all relationships. Hence, there is more integration of coordination mechanisms

than in the previous category. In the case of ad hoc variation, finally, there is neither a

dominant coordination mechanism nor a clear pattern of differentiation of coordination

mechanisms used across subsidiaries.

Ghoshal and Nohria (1993) predicted that MNCs that matched their pattern of head-

quarters–subsidiary relationship to their environment would be most successful. The

differentiated fit pattern was expected to do best in an environment characterized by high

pressures for localizing and weak pressures for globalizing (i.e. calling for a multidomestic

approach). The structural uniformity pattern fits best in an environment with strong

pressure to globalize and weak pressure to localize (the global approach), and the inte-

grated variety pattern in environments with both strong pressures to localize and to

globalize (transnational management). Based on their limited dataset of 41 MNCs the

authors came to the conclusion that MNCs that managed their headquarters–subsidiary

relationships in a way that fits their environment did indeed perform better than the other

MNCs, in terms of return on net assets, growths of these returns and revenue growth.

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 426

The upshot is that effective MNC management does not only mean that the MNC

should have the right macro organizational structure and apply the right mix of coordi-

nation mechanisms, but should also be able to differentiate its approach to different kinds

of subsidiary, as the modern MNC is a differentiated network of units, in which the func-

tion of each element to the whole determines the pattern of coordination mechanisms to

be used. In the next section we will put this complex picture in a more dynamic light, by

focusing on the question of how the internal management of MNCs enables them to learn

and develop over time.

9.4 Knowledge Management in the MNC

Increasingly, the competitive advantage of companies is seen as residing in their unique

sets of competencies and capabilities. As competencies and capabilities can be acquired or

copied by competitors, a firm has to work continuously on their further development if it

is to remain competitive (Senge, 1990). The concept of the transnational MNC fits very

well in this new perspective, as it emphasizes the importance of MNCs’ capacity to learn,

combining knowledge inputs from all of its dispersed units in flexible ways. In this section,

we will discuss the learning MNC in more detail.

Exploitative and explorative learning in the MNC

Looking at the concept of learning, it is first of all important to distinguish between

exploitative and explorative learning (March, 1991). Exploitative learning consists of the

MNC trying to become better in what it is already capable of doing; its effect is more effi-

cient operation in known fields. The essence of explorative learning is experimentation

with new alternatives. The outcome is more uncertain, but may consist of the MNC

starting completely new activities. In order to be effective, the MNC must engage in both

exploitative and explorative learning, but the balance may differ between companies,

industries and time periods. Traditional theories of the MNC, such as Dunning’s eclectic

paradigm, discussed at the beginning of this chapter, have concentrated predominantly

on exploitative learning: the MNC has a particular capability and looks for new locations

to better exploit that capability. Hence the emphasis is on the flow of knowledge from

headquarters (or the home-country organization) to subsidiaries abroad. However, if we

also focus on explorative learning, the two-way flow of information and knowledge, both

between subsidiaries and headquarters and among subsidiaries, becomes more

important. Moreover, a more balanced view of the motives for foreign expansion is due.

MNCs not only invest abroad to further exploit their existing capabilities, but also to be

able to acquire new knowledge. This type of foreign investment can be called ‘knowledge-

seeking FDI’ (Makino and Inkpen, 2003: 239). This means that the MNC invests in

certain countries or regions because it seeks critical capabilities that are bound to those

locations (e.g. because they reside in local inter-firm networks). An example is the City of

London as an attractor of FDI from knowledge-seeking MNCs in the financial services

sector (Nachum, 2003).

Organizing for explorative learning puts different demands on the MNC: ‘the distance

in time and space between the locus of learning and the locus for the realization of

MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS: STRUCTURAL ISSUES 427

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 427

returns is generally greater in the case of exploration than in the case of exploitation, as

is the uncertainty’ (March, 1991: 85). Hence, it becomes unpredictable where in the MNC

new knowledge will originate, and where it will be put to use. As a consequence, the MNC

also cannot tell which of the many potentially important intra-firm relationships it has to

invest in and foster. For the transnational this is a crucial issue, for the capability of the

MNC to effectively transfer know-how and capabilities from one unit to another is far from

self-evident (Cerny, 1996). Buckley and Carter (1999: 80) observe that ‘organizational

and cultural barriers internal to the firm become a prime concern when the firm’s man-

agement is seeking the most effective use of its intangible knowledge assets’ (‘intangible

knowledge assets’ referring to know-how and capabilities).

Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) distinguish between four types of subsidiary, in as

far as their role in MNC knowledge development is concerned. Some subsidiaries, ‘global

innovators’, serve as the source of knowledge in a particular field for all other parts of the

MNC. Other types of subsidiary (‘implementers’) receive knowledge from headquarters or

other subsidiaries and apply it locally, without transferring any knowledge back to other

parts of the MNC. ‘Integrated players’ both give and take, sometimes and in some areas

functioning as the source of information, and at other times or in other areas of knowl-

edge as the receptor. ‘Local innovators’, finally, do develop new knowledge, but this

remains specific to their own area of application, and is not shared with other parts of the

MNC. Traditionally, MNCs consisted predominantly of foreign subsidiaries acting as

implementers and local innovators, the bulk of the innovation coming from the home

country organization. This made the demands placed on the MNC organization in terms

of communication and coordination relatively easy and predictable. Local innovators and

implementers require less communication and coordination than the two other types of

subsidiary. Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) predict that global innovators and integrated

players will be linked to the rest of the MNC through various integration mechanisms and

more intense communication.

In a later empirical study, these authors found that coordination mechanisms

allowing for rich information transmission (in terms of the informality, openness and

density of the communication) positively and significantly influence both the outflow of

knowledge from subsidiaries to other parts of the MNC and the inflow into the subsidiary

of information from other parts of the MNC (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000). They found

this effect both for formal integrative mechanisms (liaison personnel, task forces, perma-

nent committees) and for more informal corporate socialization mechanisms (job

transfers among subsidiaries, and between subsidiaries and headquarters, participation

in multisubsidiary executive programmes, participation in corporate mentoring pro-

grammes). These types of coordination mechanism all seem to fall under the rubric of

what we have called ‘socialization and networks’.

The costs of transnational management

The upshot of the discussion in the previous subsection seems to be that transnational

management emphasizing both exploitative and explorative learning not only requires the

MNC to invest in intensive, and hence costly, coordination mechanisms, but also impedes

a strict a priori selection of the intra-firm links to invest in. With regard to this second

issue, headquarters cannot predict where in the MNC network crucial new knowledge

428 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 428

can be developed by what combination of subsidiaries, so all possible links should, in prin-

ciple, be kept open. This strategy, however, obviously entails costs that can easily become

prohibitive. The theoretical number of links varies between network structures. In a ‘star

structure’, one central node is connected to all other nodes, which remain unconnected

to each other. In this structure, the number of links is equal to the number of nodes. If an

MNC with such an internal structure has n subsidiaries, it also has n intra-organizational

links to maintain. This would be the archetypical international or multidomestic type of

MNC, in which only headquarters–subsidiaries relationships are invested in, and links

between subsidiaries remain unimportant. The transnational, however, can better be

compared with the theoretical structure of the ‘fully connected network’, in which each

node is directly connected to each other node. Here, if n is the number of nodes, the

number of links becomes (n

2

n)/2. As an example, take an MNC with 20 local sub-

sidiaries. In a star structure, the number of intra-firm relationships would be 20; but in a

fully connected network, the number of links to be maintained would be no less than 190.

Clearly the costs of maintaining a network of this size can become a serious competitive

disadvantage, at least if the links are to be of the kind that enables the exchange of knowl-

edge that is often difficult to codify.

This brings us to the other point. Transnational MNCs rely relatively much on

expensive forms of coordination. Hierarchical coordination and bureaucratic control pro-

cesses are less important than in the more traditional forms of MNC management. These

coordination mechanisms – and the same is true of output control – are not very con-

ducive to the speedy, improvised and high-quality exchange of ideas associated with

explorative learning in a differentiated network of MNC units. The knowledge to be

exchanged will very often be partly implicit and difficult to codify. As a result the MNC

must extensively use coordination mechanisms that allow unstructured information to be

exchanged between units in a flexible way. As a result there will be, relatively, much

emphasis on coordination through socialization and networks.

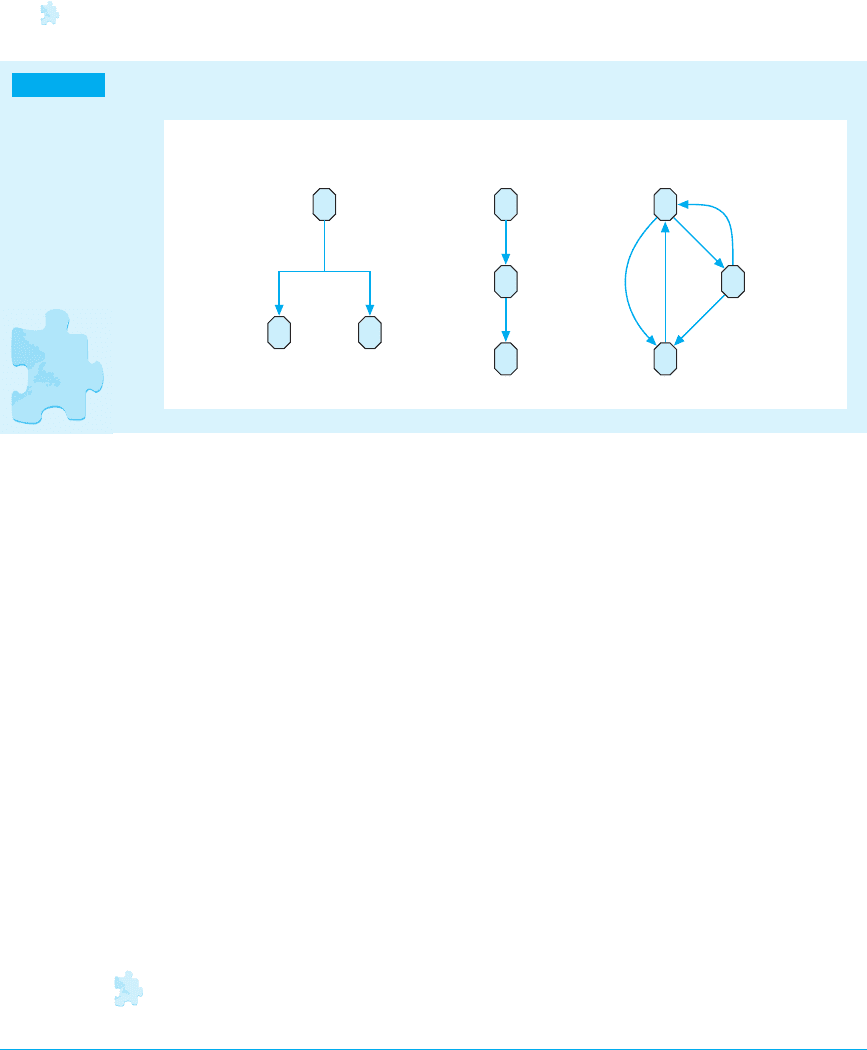

This can be clarified with the distinction Thompson (1967) made between various

types of interdependence between individuals or units. Thompson distinguished between

three types of interdependency (see Figure 9.6). In the case of pooled interdependence, two

units depend on the inputs from a third unit for their own tasks. However, after having

received this input the two units can function independently from each other. If there is

sequential interdependence, one unit depends on the inputs from a second unit for the fulfil-

ment of its task, and a third unit in turn is dependent on its own output. Reciprocal

interdependence, finally, is the term Thompson uses for situations in which units depend on

each other’s outputs in complex and unpredictable ways.

The three kinds of interdependency can be linked to the types of coordination mech-

anisms discussed earlier in this chapter. Pooled interdependence exists, for instance,

between the subsidiaries of a multidomestic MNC. They are all dependent on headquar-

ters’ decisions with regard to targets and budgets, but once these have been decided upon,

each subsidiary can go its own way. This type of interdependence can be managed

through output control. Sequential interdependence is typical of the relationship between

functional departments within a firm. Within an MNC the various production units will

often be organized internally along these lines (the following discussion is based on

Egelhoff, 1993). Sequential interdependence can effectively be managed through bureau-

cratic formalized control if the issue is of a routine nature, and through hierarchical

MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS: STRUCTURAL ISSUES 429

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 429

430 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

referral (personal centralized control) if it concerns non-routine issues. Reciprocal inter-

dependence is the kind of interdependence between parties engaged in complex tasks.

This is the type of interdependence that at the micro level can be found within depart-

ments of units. If this type of interdependency pertains to routine issues, it can be

managed through information systems that allow all parties concerned access to a

dynamic and interactive database. If the issue is non-routine, however (as in the case of

explorative learning within the MNC), the information that needs to be exchanged and

discussed will typically not be the type of standard data one can find in the company’s

computer systems. Hence, coordination forms that allow for rich, face-to-face information

exchange are called for. These are the socialization and networking kinds of coordination

mechanism, like task forces consisting of members from different units and/or depart-

ments, teams, managers with integrating roles, and so on. It is not possible to

unambiguously rank the coordination mechanisms according to their cost. For instance,

personal centralized control requires little set-up cost, but the ongoing costs of main-

taining this type of coordination are relatively high. For bureaucratic formalized control,

it is just the other way around. At any rate, control by socialization and networks can be

characterized as high cost, meaning that the management of transnationals as envisaged

by Bartlett and Ghoshal (1989) may very well be prohibitively expensive.

9.5 The MNC and Cultural and Institutional

Differences

In this final section of the chapter we will discuss how cultural and institutional differ-

ences impact on the MNC. In a way, the entire chapter has focused on this issue, for it is

mainly because of this cultural and institutional diversity that the management and

organization of MNCs is different from that of large domestically operating firms. Here,

however, we will first reiterate what the influence of cultural and institutional diversity on

MNCs can be expected to be, and inspect the (scarce) relevant empirical evidence. After

that, we will look at the issue from a different angle, and explore the question of ‘country-

Figure 9.6 Thompson’s interdependencies

Pooled

interdependence

Sequential

interdependence

Reciprocal

interdependence

Source: adapted from Thompson (1967).

MG9353 ch09.qxp 10/3/05 8:47 am Page 430