Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

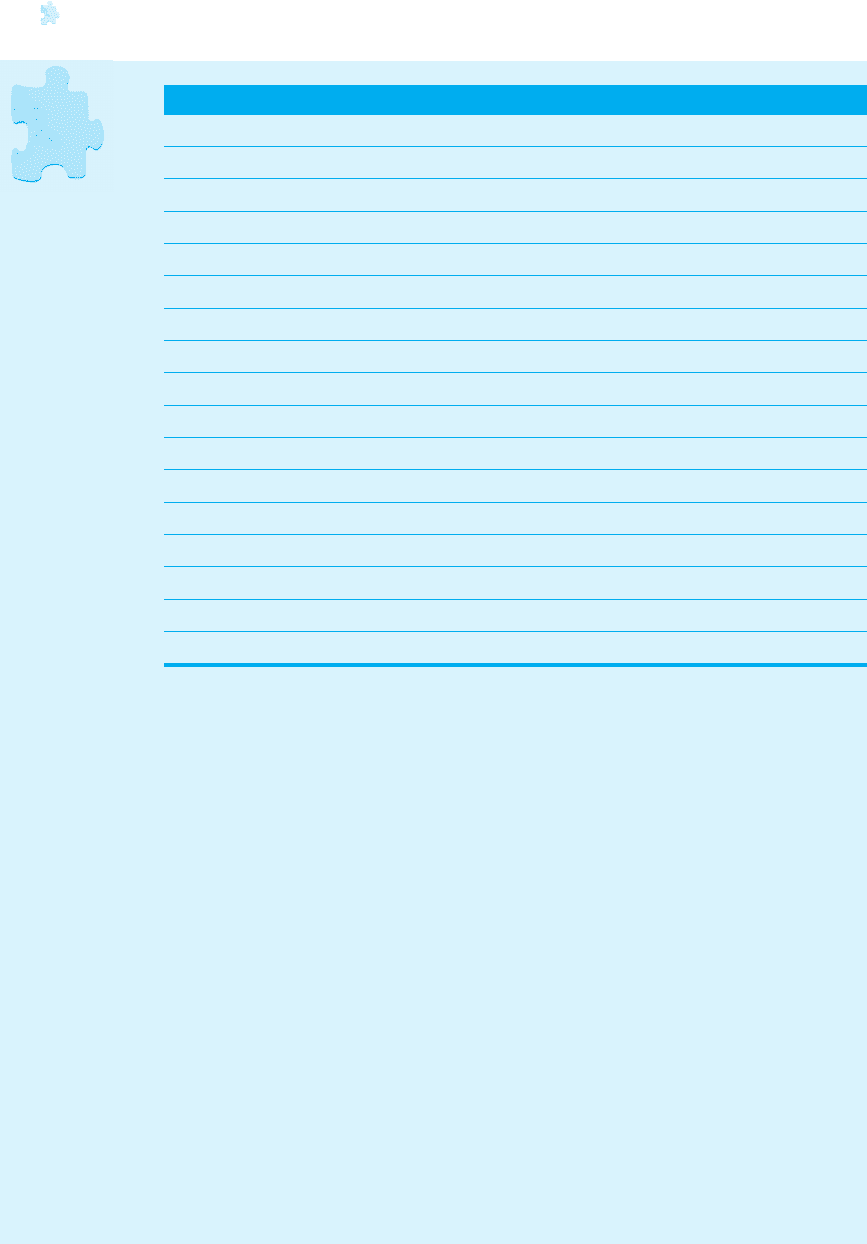

MANAGING RESOURCES: NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS 391

trade barriers. The market share of 20 per cent represents Japan’s protectionism

far more than the superior competitive performance of its pharmaceutical firms.

Source: Teso (1980); Grabowski (1989); Thomas (1994); Sharp et al. (1996); ABPI (2000), and own calculations.

*R&D intensity is measured as a percentage of sales.

**The three best-selling drugs of SmithKline Beecham are credited to both the USA and the UK, since the company is of joint ownership.

Table 8.1 International comparison of market features

US Japan Germany UK

World market share

1985 43.3 20.2 10.2 7.4

External share

1985 19.1 0.1 6.2 5.8

Firm market share in the USA

1982

1991

80

70.2

n.a.

0.3

3.9

4.6

5.1

14.6

Percentage discovery global

1965–85 44 9 18 51

Percentage discovery local

1965–85 28 77 49 25

R&D intensity (%)*

1964

1974

1983

1992

7

11

10.6

14.3

3

4.5

6.7

9.8

5

9

8.4

9.2

5

10

11.7

16.3

New chemical entities (NCEs)

1961–70

1971–80

1981–90

202

154

142

78

74

129

112

91

67

45

29

28

Origin of major drugs (%)

1950–66

1970–83

48.6

42

0.7

4

10.9

10

7.2

10

No. of products in top 50

1985

1990

23

27**

5

2

5

5

9

12

No. of products in top 25

1998 16 0 2 5

No. of firms that innovate/R&D

1965–85 3.6 12.2 5.9 4.8

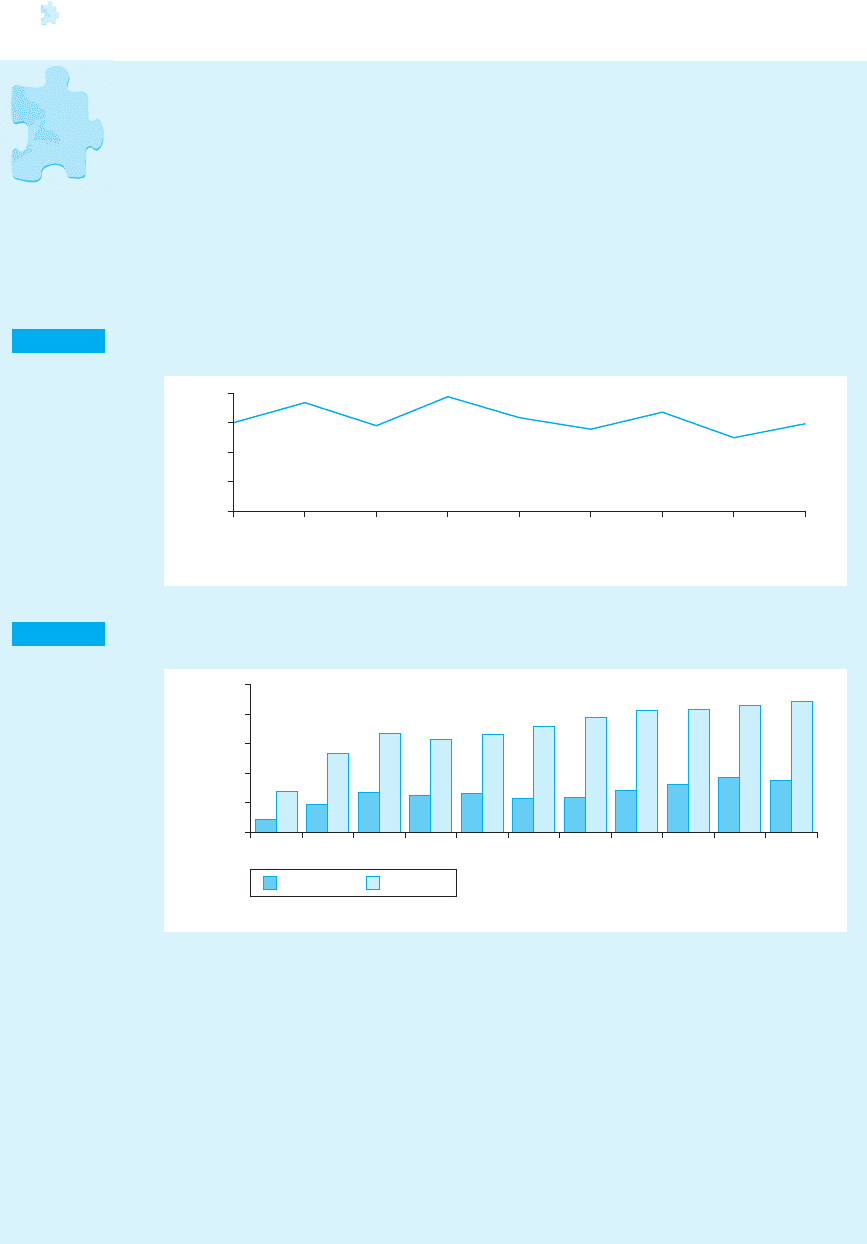

The poor export performance of the Japanese pharmaceutical sector con-

firms these observations. The Japanese pharmaceutical industry has been one of

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 391

392 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

the least prolific exporters among the pharmaceutical industries of the major

producing countries. For most of the postwar period, the Japanese pharmaceu-

tical industry has exported only about 3 per cent of total production (Figure 8.1).

In comparison, during the 1980s and 1990s, the USA (the largest drug market)

exported approximately 9 per cent of its pharmaceutical production, France 21

per cent, the UK 55 per cent and West Germany 24 per cent. Even in 1993, in

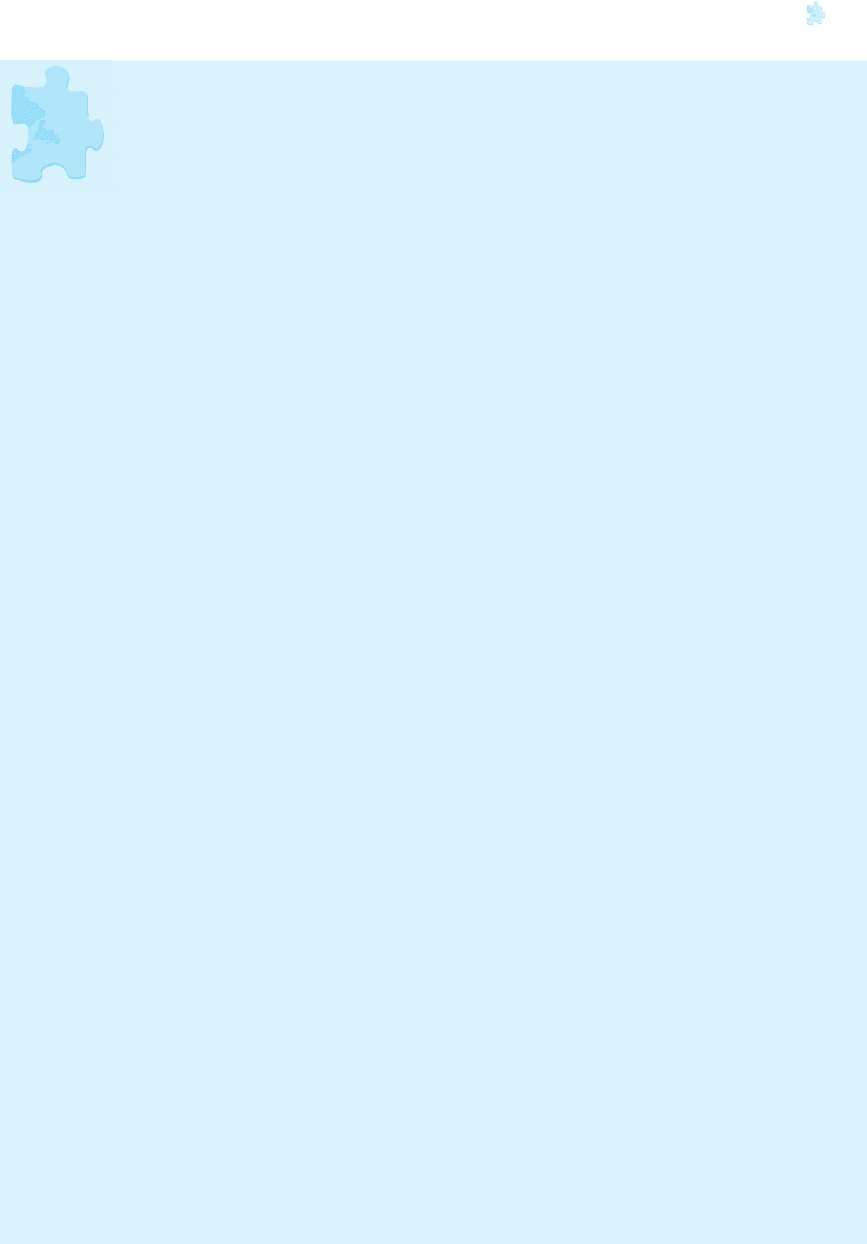

Japan, pharmaceutical imports exceeded exports by about two and a half times

(Figure 8.2). It must be noted that the relatively low export rate of the USA can be

Figure 8.1 Ratio of exports to production – Japanese pharmaceuticals 1955–93 (percentage)

1955

0

Year

Per cent

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1993

1

2

3

4

Source: own calculations from JPMA, Databook (1990 and 1994).

explained by the fact that most major US pharmaceutical firms have foreign pro-

duction facilities (Taggart, 1993: 27). This is not the case for Japanese companies.

The poor performance of Japan’s pharmaceutical firms becomes more pro-

nounced when looking at external market share. ‘External share’ is defined as the

sales by firms of a given nation achieved outside that nation’s borders as a share

of pharmaceutical sales in all external markets (Thomas, 1994: 453). Using this

indicator of competitiveness for 1985 we find that Japan is an exceptionally weak

performer, with a market share of 0.1 per cent while German performance (6.2

per cent) compares well with that of the UK (5.8 per cent). With an external

market share of 19.1 per cent in 1985, the USA is an exceptionally strong

competitor.

Figure 8.2 Pharmaceutical trade Japan – 1975–93 (million yen)

19931992199119901989198819871986198519801975

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

Exports Imports

Source: JPMA, Databook (1994).

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 392

MANAGING RESOURCES: NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS 393

In addition, Japanese pharmaceutical firms are not competitive in the US

market. Firm market share in the USA could be seen as a crude measure of com-

petitiveness because the US market is the most open and competitive in the world

(Casper and Matraves, 1998: 4). In 1991, Japan’s market share in the USA was

negligible (0.3 per cent) in comparison with that of Germany (4.6 per cent) and the

UK (14.6 per cent). The German pharmaceutical share of the US market, on the

other hand, is low relative to that of the UK. In fact, Table 8.1 shows that

Germany’s share of the US pharmaceutical market has not increased much from

the 1980s onwards and, as a consequence, has dropped far below the UK share.

The latter can be clarified partly by looking at the types of innovation in each

country’s pharmaceutical industry.

In this respect, Table 8.1 shows that strong competitive performers such as

the USA and the UK concentrate on developing significant innovations – the so-

called global or consensus drugs – that can be marketed effectively in the major

pharmaceutical markets (Grabowski, 1989). Between 1965 and 1985, the per-

centage of innovations discovered in the USA and the UK that were global

products was 44 and 51 respectively, while under 30 per cent are less significant

local products. Germany and Japan, in contrast, concentrate essentially on the

development of local as opposed to global products. During the period 1965–85,

German innovation was more local (49 per cent) than global (only 18 per cent).

With 77 per cent of its innovations local products and only 9 per cent global, Japan

is in the weakest position. While local products do, indeed, represent incremental

innovations, they also stand for products that diffuse to only a few countries. This

observation, combined with the fact that Germany and Japan are not competitive

in the US market (or, in other words, that a large number of the German and

Japanese pharmaceuticals are unable to clear the stringent regulatory hurdles of

the USA), allows us to argue that Germany and Japan’s local products are not

always of high quality.

An examination of the number of NCEs, combined with the origin of major

NCEs, provides us with confirmation of the dominance of local, lower-quality

products among German and Japanese discoveries. The last measure is included

to account for the fact that although some NCEs introduced are genuinely orig-

inal, others may be marginal improvements only, which could make the NCE

figures misleading (Sharp et al., 1996: 24).

Looking at R&D intensity, it can be seen that from the 1960s until the late

1980s, the lowest R&D-to-sales ratio was in Japan, although between 1983 and

1992, expenditure did rise substantially. Japan also significantly increased its pro-

portion of NCEs between 1981 and 1990 (from 74 to 129). Evidence shows,

however, that if the number of breakthrough NCEs is considered, Japan is in the

weakest position (only 4 per cent between 1970 and 1983). The steady rise in UK

pharmaceutical performance is expressed in the substantial increase in R&D

expenditure from the 1960s onwards. Moreover, while, during the 1971–80 period,

only 29 new drugs were developed in the UK, a relatively high percentage of these

turned into blockbusters (on average, ten drugs per year turned into blockbusters

over the period 1970–83). Germany’s position is rather dubious. German

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 393

394 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

pharmaceutical companies developed far more drugs (91 NCEs between 1971 and

1980) and, like the UK, produced a number of blockbusters (an annual average of

ten between 1970 and 1983). German companies must therefore have developed

a high number of drugs that are marginal improvements at best. The US pharma-

ceutical industry is the strongest, in terms of the highest introduction of NCEs and

the largest number of blockbuster drugs.

A last measure of competitive performance that is discussed here is the dis-

tribution of innovative effort among innovating firms. In this respect, Table 8.1

reports the number of innovative pharmaceutical firms for each of the four coun-

tries divided by billions of dollars of domestic pharmaceutical R&D. For the

strongest competitive performer, the USA, innovative effort is concentrated in a

handful of firms. The innovative effort in Germany is slightly more fragmented

than in the UK, but less than in Japan. In the weakest competitive performer,

Japan, each billion dollars’ worth of pharmaceutical R&D expense is fragmented

into 12 different firms. Concentration of innovative efforts into a small number of

firms in the USA and the UK has led to significant global success (Thomas, 1994).

Conversely, the fragmentation of innovative effort into large numbers of minor

derivative products discovered by weaker firms in Japan has contributed to com-

petitive failure. Germany’s pharmaceutical structure and performance are

situated somewhere between those of the UK and Japan.

Summing up this data on country-level performance in pharmaceuticals, it is

clear that US and UK pharmaceutical firms are stronger players than German and

Japanese ones. Japan shows the weakest performance level. The German phar-

maceutical sector, on the other hand, while showing a higher capacity to develop

competitive drugs than Japan, nevertheless also adopted strategies that resulted

in the development and production of poor-quality drugs. Aside from providing

further evidence in this direction, in order to understand the reasons for the strat-

egies pursued by pharmaceutical firms based in Germany and Japan we will turn

now to an institutional explanation of firm strategy and performance.

An industrial policy for the pharmaceutical industry –

safety regulation

National regulations in the pharmaceutical industry have sought to achieve goals

along two broad axes. The first axis, stimulated by the Thalidomide tragedy of the

early 1960s, has focused on the safety, quality and efficacy of drugs. The second

axis of regulation was stimulated by the rapidly increasing cost of drugs combined

with the ageing of the population, and has focused on drug pricing. This case

study shows that the way in which governments have approached these two axes

of regulation has been a central factor in setting the product market strategies of

their domestic pharmaceutical industries.

Turning first to the regulation of drug safety, from the 1960s onwards, most

OECD governments, including those of Germany and Japan, enacted an array of

nationally distinct regulations to govern the approval of new drugs. With the adop-

tion of the 1967 act, the Japanese government installed a system whose

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 394

MANAGING RESOURCES: NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS 395

preclinical trials and clinical standards not only differed from those of the West

but also required locally generated supporting data. Specifically, this new

regulatory regime called for lengthy and costly preclinical and clinical trials to be

repeated according to unfamiliar Japanese standards, resulting in delaying the

entry of foreign innovators. Moreover, until the mid-1980s, drug approval regu-

lations also prohibited foreign firms from applying for the first step of drug

approval, the demonstration of efficacy and safety review. The aggregate impact

of all new requirements in Japan was to erect a protectionist edifice, limiting

competition in the home market and directing the benefits of the large domestic

market primarily to domestic companies (Reich, 1990). As a result Japanese

pharmaceutical manufacturers were discouraged to learn to be competitive in the

global market.

In addition, the act contained an element that induced the Japanese pharma-

ceutical industry to take an incremental, low-risk approach to the drug discovery

process rather than to pursue high-risk/high-cost pharmaceutical break-

throughs. After 1967, the regulatory system in Japan was predicated on

demonstrating merit for a new chemical entity as necessary for approval.

However, merit could be shown in a variety of relatively modest ways – for

example, improved pharmacokinetics leading to a simplified dosage, higher

potency, and the like (Neimeth, 1991: 158–9). The lenient attitude towards inno-

vation, and the neglect of efficacy demands until the late 1980s, explain the local

nature of most Japanese drugs.

In Germany, the Thalidomide tragedy intensified debates on drug safety and

efficacy. However, until the mid-1970s, no serious government efforts were made

to regulate drugs. The medical law of 1961 simply demanded the registration of

new and old drugs with the Federal Health Office (Bundesgesundheitsamt, BGA).

In fact, the public health administration only occupied itself with industrially pro-

duced drugs when it was beneficial for the industry – for example, with the

introduction of quality certificates to support the industry’s export efforts

(Baumheier, 1994). It seems that German policy-makers were concerned more

with industrial performance than with drug safety and efficacy.

In the mid-1970s, as a result of a new drug scandal, combined with the fact

that drug safety guidelines were being prepared within the European Community,

the pressure on the German government to come to a fundamental reform of its

drug safety regulations gathered force. At that time, too, the lack of a govern-

mental control system was increasingly hampering exports of German

pharmaceuticals. Hence it was, in fact, in the interests of the German pharma-

ceutical industry that its products could pass official drug safety tests. However,

while the 1976 Arzneimittelgesezt (drug safety law) introduced thorough drug

safety regulations, its administration was less exacting than its counterparts in

the USA and the UK, and mandatory efficacy thresholds were correspondingly

lower (Baumheier, 1994). Moreover, companies were given until 1990 to have all

of their products registered by the BGA. By 1998, however, there were still prod-

ucts on the market that had not been submitted for BGA approval and that often

suffered from poor quality.

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 395

396 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

The Japanese and German governments’ approaches to drug safety regulation

had a pronounced effect on the constitution of both countries’ pharmaceutical

market (which makes the majority of the figures in Table 8.I easy to understand).

In Japan, both limited competition in a large domestic market for pharmaceuticals

and the approval of small-step innovation resulted in a product market strategy

that focused on modest advances by existing agents, whose development was rela-

tively quick, simple, inexpensive and risk free – and whose registration was

virtually guaranteed. The late introduction of regulation in Germany, and the

lenient administrative controls once regulation was introduced, explain why,

rather like Japan, Germany has a substantial amount of local products that are

incremental innovations only, not always of high quality, and unsuitable for export

to stringent regulatory environments like the USA and the UK.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the UK and the USA introduced stringent safety

and efficacy regulations. The stringency of these regulations forced firms that

were based in both countries to develop significant innovations of a high quality,

as it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain approval for minor derivative local

products in the UK and US markets (Thomas, 1994: 463). It follows that the strin-

gency of regulation in the USA and the UK also helped to explain the significant

drop in the amount of new chemical entities discovered in the USA after the adop-

tion of the Kefauver Amendments in 1962, and in the UK after the creation of the

Committee on the Safety of Drugs in 1964 (see Table 8.1). The more lenient and

protectionist approach to regulation in Germany and Japan respectively explains

why the decrease in the development of new chemical entities was markedly less

in these countries. It also accounts for the lower degree of research intensity in

Germany and Japan than in the UK and the USA (Table 8.I).

The German and Japanese approach to drug regulation also explains why

innovative efforts in these countries are more fragmented than in the UK and the

USA. The stringency of regulation in the USA and the UK has resulted in a shake-

out of innovative firms. At the beginning of the 1960s, after the introduction of

safety and efficacy regulations in both nations, a host of smaller and weaker firms

were forced from the market, either through acquisition by stronger firms or

simple cessation of pharmaceutical innovation (Thomas, 1994: 462). It is essential

to note, however, that this was in the early period when biotechnology was not yet

popular, and alliances between small and large pharmaceutical firms were of

little importance. The belated introduction of official drug-approval processes and

the leniency of administrative control in Germany explain why a large number of

smaller companies, which concentrate on local products, have been able to

survive. Some suggest that the lenient controls over drug approval could be seen

as an indication of the forthcoming, almost protectionist, attitude of the German

Economics Ministry towards Germany’s small- and medium-sized companies.

The absence of protectionist elements in regulation, or the existence of an open

domestic environment, on the other hand, explains why innovative efforts in

Germany are less fragmented than they are in Japan.

The argument that concentrates on the local focus and often poor quality of

German and Japanese drugs can be supported further by evidence that shows the

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 396

MANAGING RESOURCES: NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS 397

degree of access that certain types of drugs have to both countries’ pharmaceutical

markets. With this in mind, Table 8.2 shows that, with the highest access rate for

drugs of all types, Germany is the least restrictive of the major pharmaceutical com-

petitor nations in terms of access to new drugs. Countries with stringent regulatory

regimes, such as the USA and the UK, have far lower access rates and thus are less

open to new drugs. The protectionist elements in Japanese drug regulations explain

that, like the case in the UK and the USA, Japan is far less open to new drugs than

Germany. Openness to new drugs does not, of course, in itself explain the focus or

quality of these drugs. An indication of quality restrictiveness can be obtained by con-

trasting the access rate for local products with that of global products. It is noticeable

that while Germany is far more open to global than local drugs, it also ranks third in

openness to local drugs, the quality of which is often doubtful. Only France and Italy,

countries for which the low quality of drugs is well documented, have higher access

rates for these types of drugs (see Thomas, 1996). That Japan is slightly less open

than Germany to local products is not surprising since it has a protectionist regime,

which closes the market to all types of drugs. The leniency of Japanese regulation,

on the other hand, explains why its market is more open to local products than the

US and UK markets. The in general restrictive character of the Japanese pharma-

ceutical market is also expressed in its low access rate for global drugs.

Source: Thomas (1996).

Table 8.2 Access rates to nine major competitor nations’ markets (1980s)

Access

all drugs

Access

global

Access

local

USA 33.8 72.7 16.9

Switzerland 38.2 78.4 13.1

UK 39.2 90.3 9.6

Germany 59.4 96.3 26.5

France 54.3 86.5 32.3

Italy 54.9 86.2 33.5

Japan 39.3 65.0 22.1

Sweden 19.1 59.6 2.9

Netherlands 25.1 61.0 3.9

An industrial policy for the pharmaceutical industry –

drug price regulation

A second foundation of pharmaceutical industrial policy is the regulation of drug

prices. Pricing policy is of crucial importance for the pharmaceutical industry. The

need to recoup enormous R&D costs during the period that a drug enjoys patent

protection means that too-low drug prices would discourage innovation. A too-

generous price level, on the other hand, could be seen as a form of promotional

policy. In the absence of price intervention, the oligopolistic market structure

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 397

398 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

allows the industry to earn monopoly rents by charging prices above costs that

recoup long-term development costs (Koen, 1995: 24–30). Ample reason thus

exists to explain why price controls are such a widespread phenomenon in the

pharmaceutical industry. This case study argues that absence of government

price controls in this sector could, in fact, be seen as an implicit form of industrial

policy.

Like safety regulation, pricing policy is handled in different ways in different

countries. This case study finds that pricing policy has a pronounced effect on the

competitive strategies and performance of firms based in the resulting environ-

ment. Also in this case, there are differences between the German and Japanese

governments’ approach, with similar effects on firm strategy. In Japan, the official

reimbursement price for all pharmaceuticals is set by the government with its

Drug Tariff. The National Health Insurance (NHI) drug price functions both as the

reimbursement rate paid by all health insurers to all medical institutions, and as

the official acquisition price recognized by the MHW for budgetary purposes.

There is, however, a considerable difference between the official reimbursement

price of pharmaceuticals, and the actual price paid by physicians and hospitals

(Howells and Neary, 1995). Pharmaceutical companies, as a matter of marketing

strategy, offer the drugs to hospitals and private physicians at a discount.

Throughout the postwar period, Japanese general practitioners and hospitals had

both prescribed and dispensed pharmaceuticals to patients, with the difference

between the purchase price from the supplier and the reimbursement price set

by the government serving as additional income. By creating economic incentives

for private physicians and hospitals to prescribe liberally and to choose products

with higher margins, this system has contributed to the expansion of the domestic

market (Reich, 1990).

Clearly, since pharmaceutical companies have been able to give substantial

discounts on drugs, reimbursement rates must have been generous. Indeed,

while international comparisons of pharmaceutical prices are subject to various

uncertainties (due to product variation and exchange rates), one study reported

Japanese prices as significantly above those in Switzerland, the UK, Italy, Spain

and France. This study confirmed that the higher price level in Japan, apart from

reflecting the strength of the yen at that time, is also a clear illustration of the fact

that Japan has consistently supported its home-based industry (Reich, 1990: 132).

In an Office of Health report, Reekie provides further confirmation of Japan’s high

drug prices. Using different exchange rates and measures for calculating prices,

Reekie shows that drugs in Japan are priced consistently higher than their

European and US equivalents (Reekie, 1981).

Reimbursement price policy has also played a major role in determining the

strategic allocation of corporate R&D funds in Japan. From the mid-1970s

onwards, downward price revisions for older drugs, combined with significant

price premiums for minor modifications, led to ‘excessive innovation for the local

market’ or, in other words, stimulated companies to concentrate on merely

altering existing drugs slightly, rather than on producing new innovative (or

global) drugs. Moreover, this policy of rewarding small-step innovation also,

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 398

MANAGING RESOURCES: NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS 399

inevitably, resulted in an upward price spiral, which led to increasing profits in the

pharmaceutical industry. Hence, it could, in fact, be argued that this price system

would have, in and of itself, and independently of the safety regulations, encour-

aged the development of mainly local products.

In recent years, however, while still cutting the prices of older drugs, the

Japanese government has only offered premium prices to drugs with a significant

therapeutic advantage, thus driving research programmes towards ‘break-

through’ drugs. Although this measure is said to be part of the MHW’s

cost-containment effort, this case argues that this also contains an industrial

policy aspect in that it forces firms to develop global drugs and punishes those

firms that are unable to do so. Moreover, MHW respondents argued that while

pricing policy is used for health policy reasons, it is also the main, if not sole,

industrial policy instrument (interviews, Tokyo, 1996–97). Consequently, while

this case accepts the argument that, initially, pricing policy could have been used

mainly as healthcare policy, it also claims that eventually, when the effect of

pricing upon industry behaviour was recognized, the MHW combined the use of

pricing policy for healthcare purposes with applying it in order to steer the phar-

maceutical industry, thus also using pricing policy as an industrial policy

instrument.

In a similar vein, this case argues that, in Germany too, pricing policy – which

in Germany means the absence of price controls until the late 1980s – could be

seen as part of an industrial policy with considerable influence on product market

strategy. Rather like Japan, Germany is also well known to be a high-price

country for pharmaceuticals. Table 8.3 shows that Germany is the second

highest-price country in Europe.This case argues that a decided non-interven-

tionist stance in an oligopolistic market is tantamount to interventionism. The

absence of price controls on pharmaceuticals until the end of the 1980s in

Germany, in a market that is known to be oligopolistic, amounts to a policy that

promotes the pharmaceutical industry.

At the end of the 1980s, as part of the cost-containment efforts in the health-

care sector, for the first time in history, the German government decided to

interfere with drug pricing and introduced a fixed-price scheme. The intention

was to stimulate price competition in the pharmaceutical market and to use this

to reduce drug spending. However, by fixing reimbursement levels by therapeutic

category rather than basing the system on individual drugs, the reference price

scheme continues to encourage oligopolistic pricing and discourage radical kinds

of drug innovation within the therapeutic categories.

The incremental bias of the German product market strategy received further

support in 1995, when the German government changed the original fixed-price

scheme. Whereas initially only ‘truly innovative’ drugs were shielded from the

fixed price scheme, from 1995 onwards, on-patent drugs were freed from price

controls. Since ‘on-patent’ drugs do not have to be truly innovative but must

include incremental innovations, the government once again sent a clear signal

to the industry that it continues to support a product market strategy that is

focused on incremental, and thus less costly, innovation.

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 399

400 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Questions

1. Institutional theory argues that Japan’s institutional framework is largely

similar to Germany’s. It also argues that national institutions largely deter-

mine a nation’s success in particular sectors. Explain briefly why – given that

Germany and Japan have similar institutional environments – the German

pharmaceutical sector has been successful internationally, and why

Japanese firms have persisted in strategies that have led to failure.

2. Explain why, despite the international success of German pharmaceuticals,

German pharmaceutical firms nevertheless also adopted strategies that

resulted in the development and production of lower-quality drugs.

3. Explain whether the incremental character of German and Japanese phar-

maceutical innovation and those countries’ high drug prices support the

institutional thesis on innovativeness.

4. Explain whether the local character or low quality of a large number of

German and Japanese drugs can also be explained within the institutional

framework.

Table 8.3 International pharmaceutical price indexes in the EU (1993)

Country index

Denmark 164

Germany 152

Netherlands 152

Austria 129

Ireland 128

Belgium 113

UK 111

Luxembourg 110

Finland 108

Sweden 108

EU-15 average 100

Portugal 77

France 76

Italy 72

Spain 63

Greece 51

Source: Senior (1996).

MG9353 ch08.qxp 10/3/05 8:46 am Page 400