Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

across different ones. They develop a greater degree of employer–employee interdepend-

ence and trust of skilled workers than employers in compartmentalized and state-organised

business systems’ (Whitley, 1999: 43–4). Prominent examples are to be found in western

continental Europe, in German-speaking countries, and also in Scandinavia.

Highly coordinated business systems are also dominated by alliance forms of owner

control and, in addition, have extensive alliances between larger companies, which are

usually conglomerates, and a differentiated chain of suppliers. Employer–employee inter-

dependence is high, and a large part of the workforce is integrated into the enterprise in

a more stable way. Japan is the most prominent example of this type of system.

Whitley’s typology is not the only one that has been developed within the insti-

tutional literature, but in organization studies in Europe it is the most frequently used and

most differentiated one.

3

Typologies are, of course, very crude tools that help us to sketch

broadly the differences between, say, Korea and Japan, but that are unable to capture the

more specific differences thus failing on more demanding analysis. In general, and also in

Whitley’s case, typologies fail to explain why a particular country develops a specific type

of business system at a particular time. In other words, there is a lack of theory building.

Typologies are useful, though, in forcing us to identify linkages between different insti-

tutional domains (Sorge, 2003).

Background versus proximate institutions

In considering the key social institutions that influence the sorts of business system that

become established in different market economies, and the ways in which they vary,

Whitley (1992a: 19) distinguishes between more basic, or ‘background’ institutions and

‘proximate’ institutions.

Background institutions are social institutions (norms and legal rules such as property

rights) that structure general patterns of trust, cooperation, identity and subordination in

a society (i.e. commitment of employees, corporate culture) (see Table 4.3).

They are reproduced through the family, religious organizations and the education

system, and often exhibit considerable continuity. They are crucial because they structure

exchange relationships between business partners, and between employers and

employees. They also affect the development of collective identities and prevalent modes

of eliciting compliance and commitment within authority systems. Variations in these

institutions result in significant differences in the governance structures of firms, the

ways in which they deal with each other and other organizations, and prevalent patterns

of work organization, control and employment. For example, how trust is granted and

guaranteed in an economy especially affects the level of inter-firm cooperation and tend-

ency to delegate control over resources. Another example is the impact of a society’s level

of individualism or collectivism. Individualistic societies such as the USA and the UK tend

to have ‘regulatory’ states, a preference for formal, contractual regulation of social

relationships, and market-based employment and skill development systems.

Proximate institutions are more directly involved in the economic system and constitute

the more immediate business environment. They are often a product of the industrializa-

tion process and frequently develop with the formation of the modern state (see Table 4.3).

NATIONAL DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT 161

3

Soskice (1991, 1994) develops a similar but less diversified typology.

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 161

162 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Source: Whitley (1999: 34).

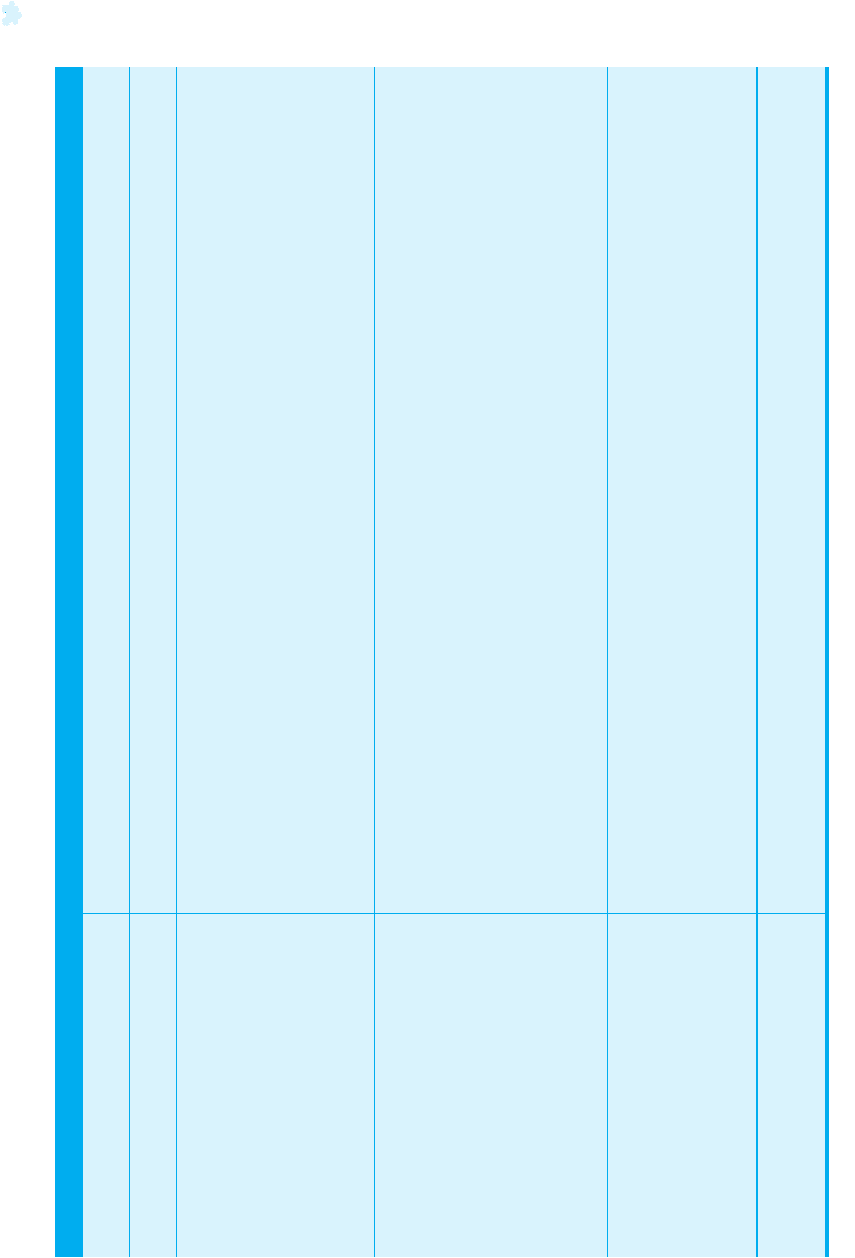

Table 4.2 Six types of business system

Business system

features

Business system

type

Fragmented Coordinated

industrial district

Compartmentalized State organized Collaborative Highly coordinated

Ownership

coordination

Owner control

Ownership

integration of

production chains

Ownership

integration of

sectors

direct

low

low

direct

low

low

market

high

high

direct

high

some to high

alliance

high

limited

alliance

some

limited

Non-ownership

coordination

Alliance

coordination of

production chains

Collaboration

between

competitors

Alliance

coordination of

sectors

low

low

low

limited

some

low

low

low

low

low

low

low

limited

high

low

high

high

some

Employment relations

Employer–employee

interdependence

Delegation to

employees

low

low

some

some

low

low

low

low

some

high

high

considerable

Hong Kong Italian districts Anglo-Saxon

countries

France

Korea

Germany

Scandinavian

countries

Japan

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 162

Proximate social institutions affect forms of business organization and, in turn,

become influenced by long-established and successful business systems. While there is no

doubt about the existence of these causal relationships, the overemphasis of the business

systems approach on ‘thick’ description is not matched by equally meticulous efforts at

spelling out and theorizing the causal relationships between the relevant variables (Foss,

1999). This is perhaps due to the fact that the approach is ‘aggregative and is not rooted

in any spelled-out theory of individual behavior’ (Foss, 1999: 4). Aside from being a

theoretical flaw, the neglect of the actor within the framework is also a lost opportunity to

explain (institutional) change and institutionalization. As is explained in more detail

below, the societal effect approach surpasses this problem by using structuration theory

(Giddens, 1986) or the ‘actor–structure’ argument.

Major societal institutions

Unlike societal effect analysis, the business systems approach is not open-ended but con-

centrates on a fixed number of dominant societal institutions that help to explain the

variations between the business systems in different countries. The framework of a priori

defined institutions and business system features, which have to be researched within the

approach, helps the researcher to focus during his/her analysis, and probably contributes

to the widespread use of the framework.

According to Whitley, the crucial institutional arrangements, which guide and con-

strain the nature of ownership relations, inter-firm connections and employment

relations – or, in other words, that help us to explain business systems – are argued to be

those governing access to critical resources, especially labour and capital. In particular,

these institutions are the state, the financial system, and the skill development and control

systems (Table 4.3).

Particularly important aspects of the state are its dominance of the economy, its

encouragement of intermediary economic associations and its formal regulation of

markets. The crucial aspect with regard to the financial system concerns the processes

by which capital is made available and priced (see Chapter 6 for an extended expla-

nation of this topic). A central distinction is made between capital-market-based and

credit- or bank-based financial systems. In the former, resources are allocated through

competition in capital markets, whereas in the latter they are allocated by the state or

by financial institutions. In terms of the skill development and control systems,

important factors are, first, the types of skill produced by education and training

systems, and the extent to which employers, trades unions, and the state are involved

in developing and managing such systems. This area also concerns the organization

and control of labour markets, in particular the strength and organization of inde-

pendent trade unions and the coordination of bargaining (see Chapter 5 for a

discussion of this topic).

Connections between dominant institutions and

business system features

In the same way as the characteristics of business systems are seen as interconnected,

interrelations between the institutions are also stressed. The political, financial and labour

NATIONAL DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT 163

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 163

164 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

institutions, together with cultural features, are argued to work interdependently to

structure business systems. Hence the explanation of differences between individual busi-

ness systems, and of changes in their characteristics, depends on an analysis of all the

major institutions and how they interdependently structure the specific form of economic

organization that has developed.

The connections between dominant institutions (Table 4.3) and business system fea-

tures (Table 4.1) enable us to identify the different institutional contexts that are

associated with each of the six types of business system outlined in Table 4.2.

4

In general,

the overall level of organizational integration of economic activities in an economy is

argued to be connected to the existence and nature of general coordinating institutions in

the wider society. Specifically, low levels of state risk-sharing, weak intermediaries and low

market regulation, coupled with weak unions, a poor public training system and low trust

in formal institutions limit the degree of organizational integration in an economy. More

organizationally integrated business systems develop in societies where institutional

mechanisms for managing uncertainty and trust are more established, and the political

and social order encourages collaboration between social actors.

Fragmented business systems

As Whitley explains, ‘fragmented business systems, then, develop in particularistic business

environments with low trust cultures where formal institutions are unreliable, risks are dif-

ficult to share, and the state is at best neutral, and at worst predatory’ (Whitley, 1999: 59).

5

Source: adapted from Whitley (1999: 48).

Table 4.3 Key institutional features structuring business systems

Proximate institutions

The state

Dominance of the state and its willingness to share risks with private owners

State antagonism to collective intermediaries

Extent of formal regulation of markets

Financial system

Capital market or credit-based

Skill development and control system

Strength of public training system and of state–employer–union collaboration

Strength of independent trade unions

Strength of labour organizations based on certified expertise

Centralization of bargaining

Background institutions

Trust and authority relations

Reliability of formal institutions governing trust relations

Predominance of paternalist authority relations

Importance of communal norms governing authority relations

4

Foran explanation of the link between dominant institutions and business system features see Whitley(1999: 54–9).

5

The following explanation of the institutional context of different business system types draws on Whitley

(1999: 59–64).

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 164

Coordinated industrial districts

Coordinated industrial districts develop and continue to be reproduced in an institutional

context in which both formal and informal institutions limit opportunism and provide an

infrastructure for collaboration to occur. ‘Local governments, banks, and training organ-

izations typically work with quite strong forms of local labour representation in these

situations to restrict adversarial, price-based competition in favour of high-quality, inno-

vative strategies based on highly skilled and flexible labour. Firm size is limited in these

localities by strong preferences for direct owner control by ‘artisanal’ entrepreneurs and

consequent high levels of skilled labour mobility, often coupled with preferential tax and

credit arrangements for small firms’ (Whitley, 1999: 61).

Compartmentalized business systems

Compartmentalized business systems develop in arm’s length institutional contexts with

large and highly liquid markets in financial assets and unregulated labour markets with a

highly mobile workforce. ‘States are here regulatory rather than developmental, and often

quite internally differentiated. . . . Unions may be influential at times but are usually

organized around craft skills rather than industries, and bargaining is decentralized.

Practical manual worker skills are not highly valued and training in them is typically gov-

erned by ad hoc arrangements with little or no central coordination. . . . Such a relatively

impoverished institutional infrastructure restricts organizational integration between

ownership units and leads to a strong reliance on ownership-based authority relations for

coordinating economic activities’ (Whitley, 1999: 61).

State-organized business systems

‘State-organized business systems develop in less pluralist, dirigiste environments where

the state dominates economic decision-making and tightly controls intermediary associ-

ations. . . . Firms and their owners are highly dependent on state agencies and officials. As

a result, they delegate little to employees and find it difficult to develop long-term commit-

ment with business partners or competitors’ (Whitley, 1999: 61–2).

Collaborative and highly coordinated business systems

‘In contrast, both collaborative and highly coordinated business systems are established and

reproduced in more collaborative institutional contexts that encourage and support cooper-

ation between collective actors. The state here performs a greater coordinating role than in

the previous case, and encourages the development of intermediary associations for mobi-

lizing support and implementing collective policy decisions’ (Whitley, 1999: 62). Markets

are typically quite regulated in these societies, limiting the mobility of skilled workers and

the price-based allocation of capital through impersonal market competition. ‘Similarly,

these kinds of business systems are much more likely to develop in economies with credit-

based financial systems in which the providers of capital are strongly interconnected with

its users and cannot easily exit when conditions alter’ (Whitley, 1999: 62). ‘Corporatist-type

bargaining arrangements based on strong unions often lead to considerable

NATIONAL DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT 165

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 165

employer–employee collaboration here. . . . Often organized around strong public training

systems in which strong sectoral or enterprise unions cooperate with employers, labour

systems in these economies encourage investment in high levels of skills which are cumu-

lative and linked to organizational positions’ (Whitley, 1999: 62). Whitley also adds that

‘Additionally, societies where trust in the efficacy of formal institutions governing exchange

relations and agreements is considerable are more likely to encourage joint commitments

between the bulk of the workforce and management to enterprise development than those

where trust is overwhelmingly dependent on personal obligations’ (Whitley, 1999: 62).

Whitley concludes by stating that ‘Essentially, I suggest that these result from vari-

ations in the extent of institutional pluralism across societies, especially with regard to

those governing the organization and control of labour power, and the concomitant dom-

inance of the state’s coordinating role. Highly coordinated business systems are more

likely to develop and continue in societies where the state dominates the coordination of

economic development and the regulation of markets, as distinct from those where banks,

industry associations, and similar organizations perform coordinating functions indepen-

dently of state guidance’ (Whitley, 1999: 62–3).

‘Perhaps, even more important in separating the two types of business system, though,

are the autonomy and influence of unions and other forms of labour representation in

policy-making processes’ (Whitley, 1999: 63). Collaborative business systems develop

when unions are strong at the national and sector level. Strong unions at the national level

limit the capacity of state–business coalitions to coordinate and integrate economic devel-

opment and restructuring on a significant scale. In particular, strong sector-based unions,

involved in national policy networks, limit state coordination of economic changes across

sectors. Additionally, powerful national unions, coupled with strong public training

systems, limit worker dependence on particular employees, which, in turn, restricts the

extent of organizational integration of manual workers within firms. Whitley adds that

‘centralized bargaining, collaboration in the management of training systems, and other

factors do, of course, encourage greater integration of the bulk of the workforce in many

firms in continental Europe than in the Anglo-Saxon economies’ (Whitley, 1999: 63).

Societies, such as Japan, that develop highly coordinated business systems have less

strong unions at the national and sector level. Japan has company-based unions, which

do not form a strong counterweight against state dominance of economic coordination.

Japan has limited public training systems. Training is organized at the company level,

resulting in high employer–employee interdependence.

Conclusions

To sum up, differences in economic organization or business systems arise from con-

trasting processes of industrialization and are reproduced by different kinds of

institutional context.

Variations in political arrangements and policies, as well as in the institutions gov-

erning the allocation and use of capital, have major effects on the extent and direction

(vertical/horizontal) of organizational integration.

Equally, the ways that skills are developed, certified and controlled exert significant

influence on prevalent employment relations and work systems, as do the dominant

norms governing trust and authority relationships.

166 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 166

NATIONAL DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT 167

All these institutional arrangements, in addition, affect the management of produc-

tion and market risks, and structure the ways that dominant firms are organized and

controlled in market economies, as well as the sorts of competitive strategy they pursue.

4.3 Business Systems Research Applied to

Taiwan and South Korea

6

As indicated, the business systems approach argues that different societal contexts or

dominant institutions encourage and constrain the development of distinctive and effec-

tive ways of organizing economic activities, or business systems, which constitute the

dominant hierarchy-market configurations. Of course there are deviant patterns from the

dominant one, but these can easily be identified. For instance, while there are some large

capital-intensive firms in Taiwan, these are either state owned, or controlled and sup-

ported (such as Formosa Plastics), and do not reflect the dominant pattern of specialized,

family businesses interconnected through elaborate personal networks. The focus here is

on forms of business organization in South Korea (henceforth referred to as Korea) and

Taiwan that compete effectively in the world markets or, in other words, on the ways of

organizing competitive economic activities. The analysis of the business systems features

deals with the situation in the 1980s and 1990s. The dominant institutions that together

help to explain these features, and how they do so, are also discussed briefly. The intention

is to help you understand how to apply the business systems approach, as well as to

provide you with a brief account of two less well-known business systems.

The major distinguishing features of the postwar business systems in Korea and

Taiwan are summarized in Table 4.4. These features were established between 1960 and

1990, and remained largely unchanged in the 1990s. Some features are quite similar in

both business systems, particularly those concerned with employment relations and own-

ership control. There are also, however, significant differences between the two; these are

to do with firm size, ownership integration and horizontal linkages in particular.

The Korean business system

Ownership relations

The Korean economy is dominated by very large family-owned and controlled conglom-

erate enterprises called Chaebol (well-known examples are Hyundai, Daewoo and

Samsung). ‘These quite diversified and vertically integrated firms have been the main

agents of industrialization in Korea since the war under the strongly directive and coordi-

nating influence of the authoritarian state’ (Whitley, 1999: 141). They dominate many

manufacturing industries (i.e. the heavy and chemical industries), as well as significant

parts of the service sector – in particular, the construction industry, transport services,

insurance and related financial services. ‘Finally, seven large general trading companies

which are members of the largest ten Chaebol have come to dominate Korea’s export

trade’ (Whitley, 1999: 142).

6

The explanation on these two business systems is based on Whitley’s research (1999: Chapters 6 and 7). For a

more detailed elaboration see the original text, as well as Whitley (1992a).

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 167

168 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

‘The Chaebol remain largely family owned and controlled, despite their rapid growth

and state pressure to sell shares on the stock market’ (Whitley, 1999: 142). In the large

Chaebol most of family holdings are indirect in the sense that owner control is exercised

through a number of core companies rather than direct family ownership in all firms. The

smaller Chaebol are more directly dominated by family owners. As Whitley states, ‘This

continuance of high levels of family ownership despite the rapid expansion and very large

size of these conglomerates was facilitated by most of their expansion being funded by

state-subsidized debt which did not dilute family shareholdings. Family ownership con-

tinues to mean largely family control and direction, with most of the leading posts held by

family members and/or trusted colleagues from the same region or high school as the

founding entrepreneur’ (Whitley, 1999: 142). Family ownership also continues to imply

strong central control over decision-making. ‘This high level of direct owner control is

implemented by substantial central staff offices that intervene extensively in subsidiary

affairs. These offices typically deal with financial, personnel, and planning matters,

including internal auditing and investment advice, and some have as many as 250 staff.

. . . The high level of centralized decision-making encouraged considerable integration of

economic activities, as capital, technology, and personnel could be centrally allocated and

moved between subsidiaries’ (Whitley, 1999: 143). The Chaebol are in fact managed as

cohesive economic entities with a unified group culture focused on the owner.

Whitley goes on, saying that ‘These strong owner-controlled large groups of firms are

highly diversified, both vertically and horizontally. According to Hamilton and Feenstra,

most are vertically integrated, with many individual Chaebol business units themselves

being quite integrated and the network of firms increasing this even more so’ (Whitley,

1999: 143). Horizontal diversification is considerable, with the average Chaebol operating

in five different manufacturing industries. For example, Samsung’s 55 firms were active in

textiles, electronics, fibre optics, detergents, petrochemicals, shipbuilding, property devel-

Source: Whitley (1999: 140).

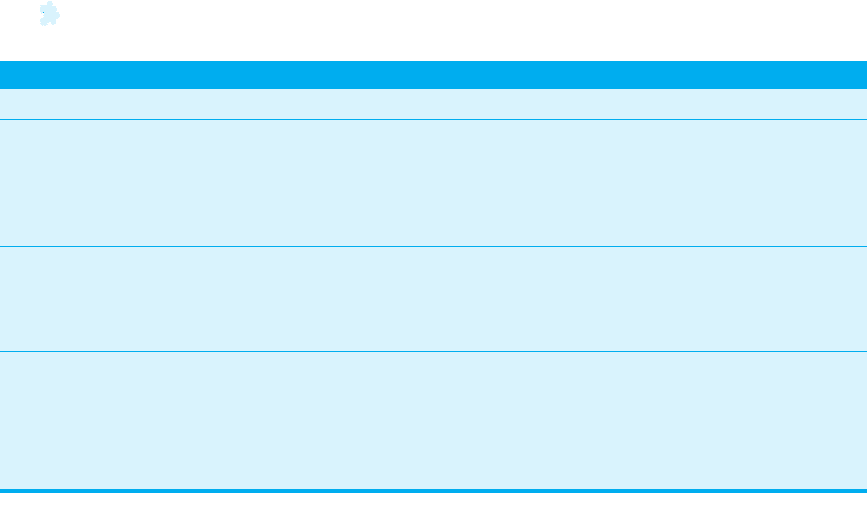

Table 4.4 The postwar business systems of Korea and Taiwan

Business system features Korea Taiwan

Ownership coordination

Owner control

Ownership vertical integration

Ownership horizontal integration

direct

high

high

direct

low except in intermediate sector

high in business groups, low

elsewhere

Non-ownership coordination

Alliance-based vertical integration

Alliance-based horizontal integration

Competitor collaboration

low

low

low

low

limited

low

Employment relations and work management

Employer–employee interdependence

Worker discretion

low except

for some

managers

low

low except for personal

connections

low

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 168

opment, construction, insurance, mass media, healthcare and higher education in the

early 1990s.

The Chaebol have grown extremely fast since the 1950s, with high growth at the

expense of profitability. Detailed analysis of the Chaebol suggests that the objective of the

firms of the large Chaebol is not to maximize profits but to maximize sales. Ownership

rights are held for control purposes more than for income, and, as indicated, growth has

been financed by state-provided and subsidized credit, rather than from retained profits.

Non-ownership coordination

Whitley explains that ‘the large size and self-sufficiency of the Korean Chaebol mean that

they exhibit low interdependence with suppliers and customers and are able to dominate

small and medium-sized firms. Typically, their relations with subcontractors are preda-

tory. As Fields comments: “Core firms are able to increase their working capital by

squeezing the subcontractors associated with the Chaebol . . . the Chaebol are able to keep

the small and medium-sized contractors under their thumbs, pass recessionary shocks on

to them, or even merge with them if it suits their plans.” . . . Relations between the

Chaebol, and between ownership units in general in Korea, tend to be adversarial, with

considerable reluctance to cooperate over joint projects, such as complementary R & D

programmes. . . . New industries especially are often the site of intense competition for

dominance, and the major driving force behind many new investments often appears to

be corporate rivalry for the leading position in them’ (Whitely, 1999: 144–5). In general,

markets are not organized around the long-term mutual obligations that characterize the

postwar Japanese economy, but rather are characterized by predominantly short-term,

single-transaction relationships. ‘These sometimes develop from personal contacts, as

when subcontracting firms are set up by ex-employees. Where cooperation does occur

between firms, direct personal ties between chief executives are usually crucial to

reaching agreements. Alliance-based modes of integration, then, are weak in the post-

war Korean business system’ (Whitley, 1999: 145).

Whitley states that ‘the high degree of competition between the leading Chaebol,

which has been fuelled by the state’s policy of selecting entrants to new industries and

opportunities on the basis of competitive success, has severely limited the development of

independent sector-based organizations in Korea. . . . In the 1980s and 1990s, however,

the umbrella organization, the Federation of Korean Industries, together with a few other

associations, attempted to diverge from and publicly influence state policies’ (Whitley,

1999: 145).

Employment policies and labour management

Whitley’s explanation of employment policies states that ‘In most Chaebol the level of

employer–employee commitment is limited for manual workers. Although seniority does

appear to be important in affecting wage rates, and employers do provide accommodation

and other fringe benefits in the newer capital intensive industries, most notably perhaps

at the Pohang Iron and Steel Company, Korean firms are reluctant to make the sorts of

long-term commitments to their workforce that many large Japanese ones do. Mobility

between firms, both enforced and voluntary, has been considerably greater for manual

NATIONAL DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT 169

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 169

workers – and some non-manual – than is common in the large firm sector in Japan.

Annual labour turnover rates of between 52 per cent and 72 per cent were quite usual in

the 1970s in Korea and were especially high in manufacturing industries. Additionally,

leading firms in Korea sometimes poach skilled workers from competitors rather than

invest in training programs. . . . White-collar employees are more favoured and tend more

to remain with large employers, not least because their pay and conditions are usually

substantially better than they could obtain by moving’ (Whitley, 1999: 145–46).

The centralized and personal nature of authority relations in the Chaebol is accompa-

nied by a largely authoritarian, not to say militaristic, management style. As Whitley

discovered, ‘According to the Japanese managers involved in joint ventures with Korean

firms interviewed by Liebenberg, the Korean management style is characterized by top-

down decision-making, enforcement of vertical hierarchical relationships, low levels of

consultation with subordinates, and low levels of trust, both horizontally and vertically.

Superiors tend to be seen as remote and uninterested in subordinates’ concerns or their

ability to contribute more than obedience. . . . This authoritarian management style

encourages close supervision of task performance’ (Whitley, 1999: 146). In order to

facilitate supervision, the physical layout of offices is arranged in a specific way and tasks

are usually described carefully. Because of the importance of personal authority in the

Korean Chaebol, jobs and responsibilities are determined more by supervisors’ wishes than

by formal rules. ‘Such strong supervision of task performance was allied to considerable

specialization of roles for manual workers. . . . Unskilled workers continue to carry out

relatively narrow tasks without much movement between jobs and skill categories.

However, non-manual workers do appear to be moved between tasks and sections, and

sometimes develop more varied skills, in the larger and more diversified Chaebol ’ (Whitley,

1999: 146). Managers in particular are often transferred across subsidiaries and have

more fluid roles and responsibilities.

Institutional influences on the Korean business system

The dominant institutions structuring the postwar Korean business system stem from

both pre-industrial Korean society and the period of Japanese colonial rule, as well as the

Korean war and the post-1961 period of military-supported rule (Table 4.5). The domi-

nant and risk-sharing nature of the Korean state can be traced back to the period between

1392 and 1910, when Korea was ruled by the Yi, or Chosun dynasty. This dynasty

entrenched Confucianism as the official ideology. This ideology is based on the idea that

the stability of society is based on unequal relationships between people. The Confucian

heritage in Korea helps to explain the population’s respect for hierarchy. During the Yi

period, ‘political power was highly centralized by the pseudo-bureaucratic elite, who

claimed moral superiority over the population on the basis of examination successes’

(Whitley, 1999: 152). The elite were awarded official posts by the king, and access to

examinations for the leading posts was restricted to those of aristocratic status. In

addition, because the possibility of obtaining a state office was always present for the

Korean aristocracy, they were discouraged from developing non-official corporate interest

groups at the local level. As Whitley states, ‘Military institutions had little prestige in the

Confucian-dominated political culture; equally Korea lacked a strong commercial class’.

The merchant class was subjected to strict surveillance. ‘In both preindustrial China and

170 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch04.qxp 10/3/05 8:43 am Page 170