Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

(d’Iribarne, 1996–97: 46). We will now examine d’Iribarne’s findings concerning the cul-

tural logics of France, the USA and the Netherlands.

The logics of honour, contract and consensus

In his principal book, Philippe d’Iribarne (d’Iribarne, 1989; summarized briefly in

d’Iribarne, 1996–97) reports on a study of three aluminium production units of the

French company Péchiney, in France, the USA and the Netherlands. The plants were

selected to employ the same technology, so that they would be comparable with regard to

the main contingency factors. Nevertheless, marked differences between the ‘collective

lives’ within the three plants are noticeable.

In France, d’Iribarne observes that the various professional groups are attached to

the privileges determined by the particular traditions of each group. These traditions

define what individual members of an occupational group should do, and also what they

cannot stoop to. The interesting thing is that this definition of what one should and

should not do is completely independent from instructions or orders from superiors.

Professional pride does not allow an employee to bow to pressure from above, if this would

go against the honour of his or her professional group. This emphasis on pride and

honour is connected by d’Iribarne to Montesquieu’s analysis of French society in the eigh-

teenth century. The influence sphere of each professional group in the organization, from

top to bottom, should be respected if managers want to avoid revolt or deceit.

It would be degrading to be ‘in the service of’ (au service de) anybody, in particular,

of one’s superiors. By contrast, it is honorable to devote oneself to a cause, or to

‘give service’ (rendre service) with magnanimity, at least if one is asked to do so with

due ceremony. Under these circumstances, the realization of hierarchical relation-

ships requires a great deal of tact and judgment. (d’Iribarne, 1996–97: 32)

In the USA a different logic prevails: the logic of the contract, freely entered into by

equals. According to d’Iribarne in the US culture, an organization is seen as ‘an inter-

locking set of contractual relationships’, and ‘great importance is attached to the

decentralization of decision making, to the definition of objectives, and to the rigor of

evaluation’ (d’Iribarne, 1996–97: 31). The link between the individual employee and the

organization, as well as that between the subordinate, and the superior, is an agreement

specifying what the parties may expect of each other. The employee may expect to be eval-

uated against explicit criteria that are well known in advance; there should be no room for

subjective opinions or feelings from the side of the superior. Hence, on one hand the

American manager has more degrees of freedom than his or her French counterpart, as

he or she is considered free to set the goals for the employee (who in turn is free to accept

or reject these goals, and face the consequences of either option). However, once the

superior and subordinate agree on a set of goals, the evaluation criteria the manager can

employ are also defined. The resulting style of management and organization is linked by

d’Iribarne by Tocqueville’s description of the ‘democratic’ relationships between masters

and servants in nineteenth-century America.

In the plant in the Netherlands, d’Iribarne identified yet another cultural logic. Here

there were no sharp divisions between occupational groups, each with their own tra-

ditions and pride, nor was there strict adherence to agreements. Instead, what struck

NATIONAL CULTURES AND MANAGEMENT 81

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 81

82 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

d’Iribarne was the process of discussion and argument necessary to settle disputes, which

were reopened as soon as the conditions of the environment changed. The use of dis-

cussion and argumentation, on the basis of factual information, was used both between

equals and between superiors and subordinates. To be a manager in Holland means to be

a master of argument and persuasion, as the use of severe sanctions is not acceptable.

Overt, or even covert, pressure is to be avoided. D’Iribarne’s view of Dutch work organiz-

ations corresponds very well to what is found in a number of Dutch sources (summarized

in Noorderhaven, 2002).

The Dutch style of consensus management is linked by d’Iribarne to the political

history of the Netherlands. The origin of Dutch institutions lies in the association of

provinces in the Union of Utrecht (1579). In the delicate balance between the provinces,

lengthy processes of persuasion and mutual accommodation were necessary to reach

decisions. Also in more recent times, the cohabitation of the different religious groups

(mainly the Protestants and the Catholics) was regulated through the same mechanisms

(d’Iribarne, 1996–97: 33).

2.6 National Cultures and Cross-cultural

Negotiations

In this final section of the chapter we will discuss from a cross-cultural perspective a very

important aspect of doing business across borders, namely international negotiations.

Negotiations play an important role in business, as the essential characteristic of econ-

omic transactions in a market system is that the parties enter into an agreement of their

own free will. In an efficiently functioning market, both parties can also consider alterna-

tives (i.e. there are multiple potential sellers and buyers). In the negotiation process with

a particular potential business partner what is at stake is closing a deal that is better than

that which could be effected with the most attractive alternative partner. The negotiation

process takes place under the shadow of the ‘best alternative to negotiated agreement’, or

BATNA (Lewicki et al., 1994). Each party’s BATNA will strongly influence what their min-

imally acceptable outcome in the negotiation process is. If the other party is not willing to

make sufficient concessions, it is better to break off the negotiations and go to the most

attractive alternative business partner.

Looking at negotiation processes in a schematic way, two possibilities exist. Either

there is an overlap between the parties’ ‘zones of acceptance’ (the set of possible deals

they are willing to accept, with the lower limit defined by their BATNAs), or there is no

overlap. In the latter case an effective communication process should make this clear to

the parties, and the negotiation process will come to an end. The problem is that com-

munication processes are not always very straightforward, and this is particularly the

case in international negotiations. In the first case (when there is overlap between the

parties’ zones of acceptance), the ultimate outcome of the negotiation remains indetermi-

nate. The parties may end up with any deal that is acceptable to both, depending on their

negotiation skills, the quality and quantity of available information, and the circum-

stances in which the negotiation takes place. But they may also end up without a deal,

simply because the communication process makes them believe that there is no overlap

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 82

between their zones of acceptance. The reason for this is that information is often deliber-

ately misrepresented in negotiations, as negotiators try to get the best deal possible.

Negotiation processes may be ubiquitous in business in general; they are an even

more salient characteristic of international business, and levels of complexity and uncer-

tainty in the international arena are also greater. Multinational corporations (MNCs) may

negotiate with national governments over the conditions under which they are allowed to

invest and to do business in a country. For instance, before Intel Corporation decided to

invest in a US$300 million chip plant in Costa Rica it went through a lengthy and

complex negotiation process with local political authorities and representatives of institu-

tions (Spar, 1998). Companies may also, however, negotiate with other companies in

countries that they seek to enter through exports or licensing, or with a strategic alliance

or joint venture. Once active in another country, managers of a company may find them-

selves engaged in negotiations with local institutions like trade unions or employers’

associations. Furthermore, processes within MNCs often have characteristics of nego-

tiation, even if the parties involved are not independent, but parts of the same company.

For instance, an MNC’s headquarters may find itself negotiating certain policies with a

local subsidiary (rather than commanding it to act in a certain way) because it believes

local subsidiary managers’ views and interests have to be taken into account if good

results are to be achieved. Finally, managers of one subsidiary of an MNC may negotiate

deals with other subsidiaries without much interference from company headquarters, as

is increasingly common in complex ‘networked’ MNCs (see Chapter 9). In many of these

cases, the negotiators and their constituencies (the companies or parts of companies they

represent in the negotiation process) are from different cultures. We will now take a quick

look at the ways in which cultural differences may influence negotiation processes.

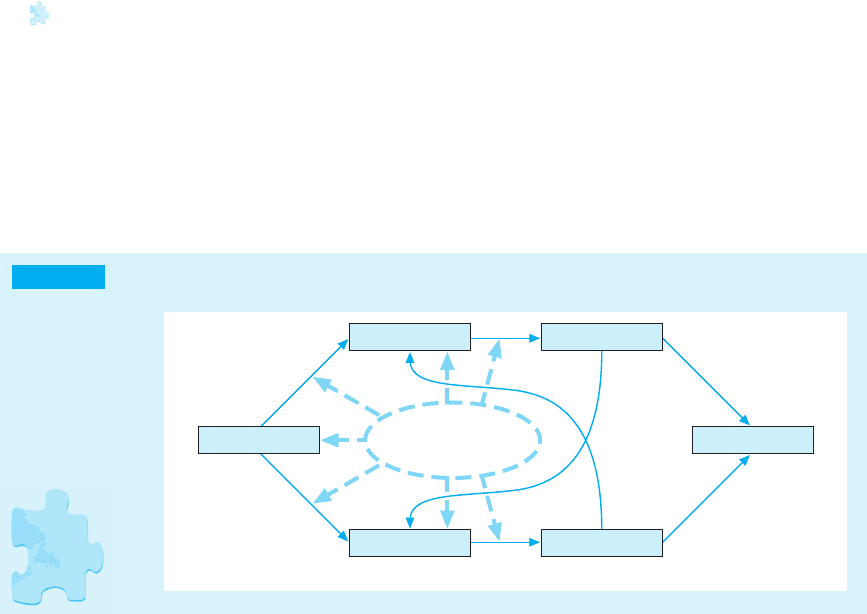

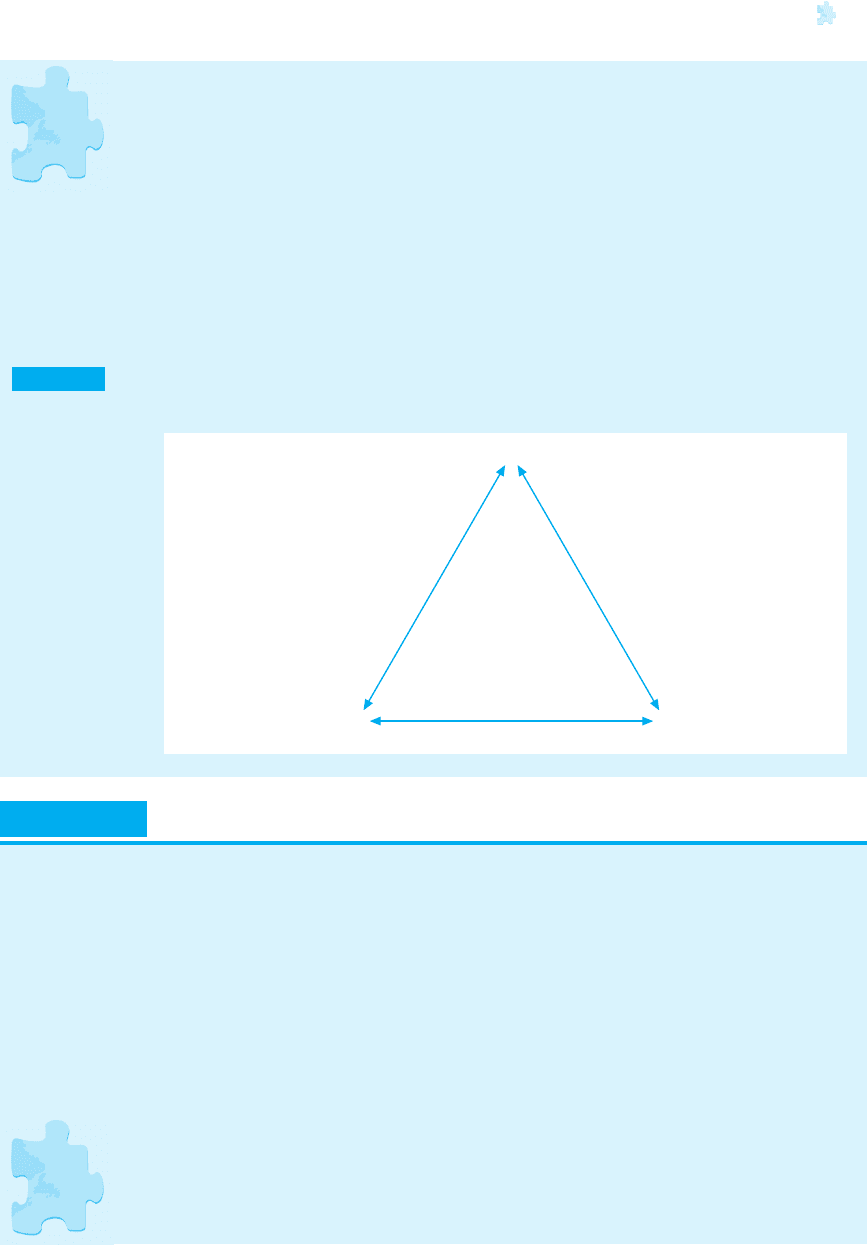

Figure 2.1 shows the elements of an intercultural negotiation process in a schematic

form. Each negotiation process takes place within a particular social situation.

1

This

means, for instance, that the negotiators fulfil certain roles (e.g. that of buyer or seller),

stand in particular relationships with their constituencies (e.g. as senior manager or as

country representative), and may face certain deadlines or other restrictions. These situ-

ational factors influence the negotiators, their perception of the situation, their

judgement, and their motives and goals. All these factors in turn influence their behav-

iour in the negotiation process (e.g. more cooperative or more competitive behaviour, the

amount of information disclosed, etc.). What makes negotiation processes so complex is

the feedback loop from the other party’s behaviour to the negotiator’s interpretation of

the negotiation process. There is a dynamic interplay between one’s behaviours, the

interpretation of these behaviours by the counterpart, his or her response, and one’s own

interpretation of the negotiation process (Bazerman and Carroll, 1987). For this reason,

negotiation processes always have an element of unpredictability.

Possible cultural influences on international negotiation processes are also indicated

in Figure 2.1. Previous research on intercultural negotiation processes has often yielded

unclear, or even inconsistent, results. For instance, some researchers find that the extent

to which negotiators reciprocate cooperative problem solving behaviour by their counter-

parts does not differ significantly between cultures. However, in other studies such

differences are identified, for example the Japanese were more likely to reciprocate than

NATIONAL CULTURES AND MANAGEMENT 83

1

The discussion in this section is based on Gelfand and Dyer (2000).

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 83

84 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

both Americans and Brazilians (Allerheiligen et al., 1985). This suggests that the influ-

ences of culture on negotiations are not very straightforward. This is reflected in Figure

2.1. Cultural influences work out on (1) the social situation in which the negotiations take

place; (2) the way in which this social situation influences the perceptions, judgements,

motives, goals, and so on, of the negotiators; (3) directly on these perceptions, and so on;

and (4) on the way in which these perceptions and so on influence the behaviour of the

negotiators. We will give some examples of each of these.

Figure 2.1 Influences of culture on negotiations

CULTURE

Social situation

Negotiator A Behaviour A

Outcomes

Negotiator B Behaviour B

Source: adapted from Gelfand and Dyer (2000).

Gelfand and Dyer (2000) state that the prevalence of types of social situation is likely

to differ between cultures. For instance, in more collectivist cultures the negotiator is more

likely to be a member of a group, even at the negotiating table, than in more individual-

istic cultures. Japanese companies are well known for sending large delegations to

negotiations with other companies, to the representatives of which the roles of the

various Japanese delegates often remain unclear. These authors also expect that in cul-

tures high on Schwartz’s mastery dimension negotiators, because they strive for

achievement and success, will feel more time pressure during the negotiation than nego-

tiators from cultures orientated towards harmony. The organizational context is also likely

to vary with the cultural environment. Organizations from large power distance societies

will have more centralized control, with the effect that key negotiations have to be con-

cluded by the top authority (Hofstede and Usunier, 1997).

Culture may also mediate the influence of the social situation on the negotiator.

Laboratory experiments show that if negotiators are required to justify their actions to

their constituencies after the negotiations, this leads to more cooperative behaviour in

terms of ego and cooperative interpretations of the behaviour of the other for collectivists,

but to more competitive behaviour and interpretations of the other’s behaviour among

individualists (Gelfand and Realo, 1999). In large power distance cultures, roles have a

stronger influence on negotiation processes and outcomes than in cultures with a smaller

power distance (Graham et al., 1994).

Culture also influences directly the perceptions, judgements, motivations, goals, and

so on, of negotiators. The negotiation context is not given objectively, but is a cognitive

construct of the negotiators, based on the information they receive, but also on their

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 84

culturally coloured expectations. Individuals use various kinds of ‘cognitive heuristics’

(subconscious ‘rules of thumb’) to make sense of ambiguous situations. One way to make

sense of a situation is to use metaphors linking the unfamiliar with the familiar.

Americans may be more likely to use (competitive) sports metaphors in interpreting nego-

tiation situations, whereas the Japanese would rather be expected to use (more

cooperative) family household metaphors (Gelfand and Dyer, 2000). Culture may influ-

ence the goals negotiators pursue particularly strongly. Whereas each party will try to get

the best outcome of the negotiation process for him or her and his or her constituency,

there are also subsidiary goals like the preservation of a good relationship, which may

carry more or less weight, depending on the culture. In more collectivist cultures main-

taining a good relationship and saving both the ‘face’ of the negotiation partner and the

respect he or she has for ego may be expected to carry relatively more weight. In more

masculine (Hofstede) or mastery-orientated (Schwartz) cultures, there will be a strong

emphasis on competitive goals (‘winning’ the negotiation), if necessary at the expense of

the relationship (Hofstede and Usunier, 1997; Gelfand and Dyer, 2000).

NATIONAL CULTURES AND MANAGEMENT 85

Case: Who has Formal Decision Rights?

2

“W

hen Honda invested heavily in an extensive relationship with British

car manufacturer Rover, workers and managers at the two

companies developed very positive working relationships for more

than a decade. The partnership intensified after the government sold Rover to

British Aerospace (BAe), but as Rover continued to lose money, BAe decided to

discard the relationship, abruptly selling Rover to BMW through a secretive deal

that caught Honda completely unaware. The Japanese auto maker had con-

sidered its connection with Rover a long-term one, much like a marriage, and it

had shared advanced product and process technology with Rover well beyond its

effective contractual ability to protect these assets. Honda’s leaders were dumb-

founded and outraged that BAe could sell – and to a competitor no less. Yet, while

Honda’s prized relationship was at the level of the operating company (Rover), the

Japanese company had not taken seriously enough the fact that the decision

rights over a Rover sale are vested at the parent (BAe) level. From a financial

standpoint, the move made sense for BAe, and it was perfectly legal. Yet Honda’s

cultural blinkers made the sale seem inconceivable, and its disproportionate

investment in Rover in effect created a major economic opportunity for BAe. The

bottom line: understanding both formal decision rights and cultural assumptions

in less familiar settings can be vital.”

Finally, culture may mediate the relationship between a negotiator’s psychic state

and his or her behaviour in the negotiation. In other words, the same interpretations,

goals, and so on, may lead to different behaviours in different cultures. For instance, the

norms concerning the display of emotions differ between cultures. Hence, negotiators

2

An excerpt from Sebenius, J.K. (2002) The hidden challenge of cross-border negotiations. Harvard Business

Review 80(3) p. 6.

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 85

from different cultures may be equally infuriated by certain kinds of behaviour, but show

their anger to a different extent. This, in turn, may lead to inaccurate interpretations by

their counterparts of the effects of the negotiation tactics employed. In negotiating with

the Japanese a westerner may get the impression that rational arguments carry little

weight: they do not seem to be able to change the opinion of the Japanese negotiators. But,

as observed by Sebenius (2002: 84), ‘in Japan, the negotiating table is not a place for

changing minds. Persuasive appeals are not appropriate or effectual’. The reason for this

is that the position taken by the Japanese negotiators is very often based on consensus

within the constituency. Changing that position is only possible if a new consensus is first

reached, which tends to be a highly time-consuming process.

As the discussion above illustrates, the influences of culture on negotiation processes

are too complex to allow for simple recommendations for managers. But it is clear that

managers negotiating across cultures should be aware of the various possible influences

depicted in Figure 2.1. This figure may also serve as a warning. Negotiators may be

inclined to see the individuals they are dealing with too much as representatives of their

culture; but the characteristics of an individual can never be reduced to a cultural stereo-

type. Rather, negotiators should try to understand the behaviour of their counterparts by

also taking into account the wider situation in which the negotiation process is embedded

(and which itself may be culturally influenced, as discussed above). Hence, the negotiator

should ‘along with assessing the person across the table, [figure out] the intricacies of the

larger organization behind her’ (Sebenius, 2002: 85). Finally, one should never forget that

language deficiencies may play an important role in international negotiations. A sense of

humour, for instance, can be very difficult to express in a foreign language, especially

when one’s command of that language is far from perfect. The use of interpreters may

help in some respects, but at the same time may introduce yet other difficulties. For

instance, if one directly addresses the interpreter rather than one’s counterpart, the latter

may take this as a sign of disrespect (Mead, 1998: 246). Interpreters may also make mis-

takes, particularly in translating slang or jokes.

Study Questions

1. Explain the concept of culture and how can it be measured at different levels of

analysis.

2. Explain the differences between ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ approaches to the study of cul-

tures.

3. What is meant by the ‘ecological fallacy’ and the ‘reverse ecological fallacy’?

4. What is meant by ‘dimensions’ and ‘typologies’ of cultures?

5. Describe and evaluate the most important research methods employed by ‘etic’

and ‘emic’ researchers.

6. What are the dimensions of culture identified by Hofstede, and what are their

implications for management and organization?

7. Explain and comment on the most important criticisms of Hofstede’s work?

86 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 86

8. What are the dimensions of culture identified by Schwartz, and how do they

relate to those of Hofstede?

9. What are the dimensions of culture identified by Trompenaars?

10. What are the main limitations of ‘etic’ approaches, from an ‘emic’ perspective?

11. Describe the ‘cultural logics’ of management in France, the USA and the

Netherlands according to d’Iribarne.

12. In what ways can culture influence international negotiations?

Further Reading

Bakhtari, H. (1995) Cultural effects on management style. International Studies of

Management and Organization 25(3), 97–118.

The study examines the effect of culture on the management style of immigrant

Middle Eastern managers in the USA.

Hall, E.T. and Hall, M.R. (1990) Understanding Cultural Differences. Yarmouth, USA:

Intercultural Press.

The authors offer yet another framework within the emic approach to national

culture, elaborating on the concepts of low and high context, and their implications

for understanding and communicating with people from different cultural back-

grounds.

Hofstede, G. (2001) Culture’s Consequences (2nd edn). London: Sage.

This book offers a quite complete picture of culture research.

Punnett, B.J. and Shenkar, O. (1998) Handbook for International Management

Research. New Delhi: Beacon Books.

This book deals in an accessible way with research design and methodology for

international management research.

Segalla, M., Fischer, L. and Sandner, K. (2000) Making cross-cultural research rel-

evant to European integration: old problem – new approach. European Management

Journal 18(1), 38–51.

This paper reports the results of a study of European managerial values. The authors

conducted a six-country study of over 900 managers working in 70 companies in the

European financial sector.

NATIONAL CULTURES AND MANAGEMENT 87

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 87

88 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Case: Unisource

Source: Van Marrewijk (1997, 1999).

T

he opening of European national telecoms markets to (international) com-

petition, which started in the 1980s, constituted both an opportunity and a

threat for national providers like the Netherlands’ PTT Telecom. The threat

was, of course, the possibility that new providers would take away business in the

domestic market. The option to expand internationally was the opportunity, and

PTT Telecom embarked enthusiastically on this course to compensate for the

potential setback of loss of domestic market share. The first large-scale inter-

national experience of Dutch PTT Telecom was the cooperation in Unisource. This

strategic alliance was meant to help the companies involved to expand their inter-

national activities, initially focusing on data communication. (Unisource was

established in 1992 as a strategic alliance between Dutch PTT and Telia from

Sweden.) In the period 1992–94 Swiss Telecom, Spanish Telefonica and AT&T

joined the alliance. However, the cooperation did not last very long: Unisource fell

apart in 1998 after various partners had joined rival alliances.

From a cultural point of view, it is interesting to note that perceptions of cul-

tural differences between the members of the alliance shifted over time. Early in

the alliance’s development, Dutch PTT Telecom managers cherished the fol-

lowing stereotypes (according to Van Marrewijk, 1997: 373).

‘Swiss colleagues are trustworthy, thoughtful, very formal and love to write

official letters. They have no international experience and are afraid of losing

control; that’s why they have so many rules.’

‘Spanish colleagues are informal, proud of their advanced technical knowl-

edge and wide international experience. They do not speak English, eat at

impossible times and exclude foreigners from their informal networks.’

‘Swedish colleagues are very much like us, not formal, people orientated and

enjoy discussions. But they also differ on many points: they have endless dis-

cussions, do not take any decisions, have less planning and control, and their

work attitude varies with the climate: in the winter it is too dark to work, in

the summer it is too sunny to work.’

However, these early expectations were subsequently put to the test in the

evolving process of cooperation. Taking a schematic and static approach, one

would expect cultural differences between the Dutch and the Spanish to be much

more pronounced than those between the Dutch and the Swedes in terms of the

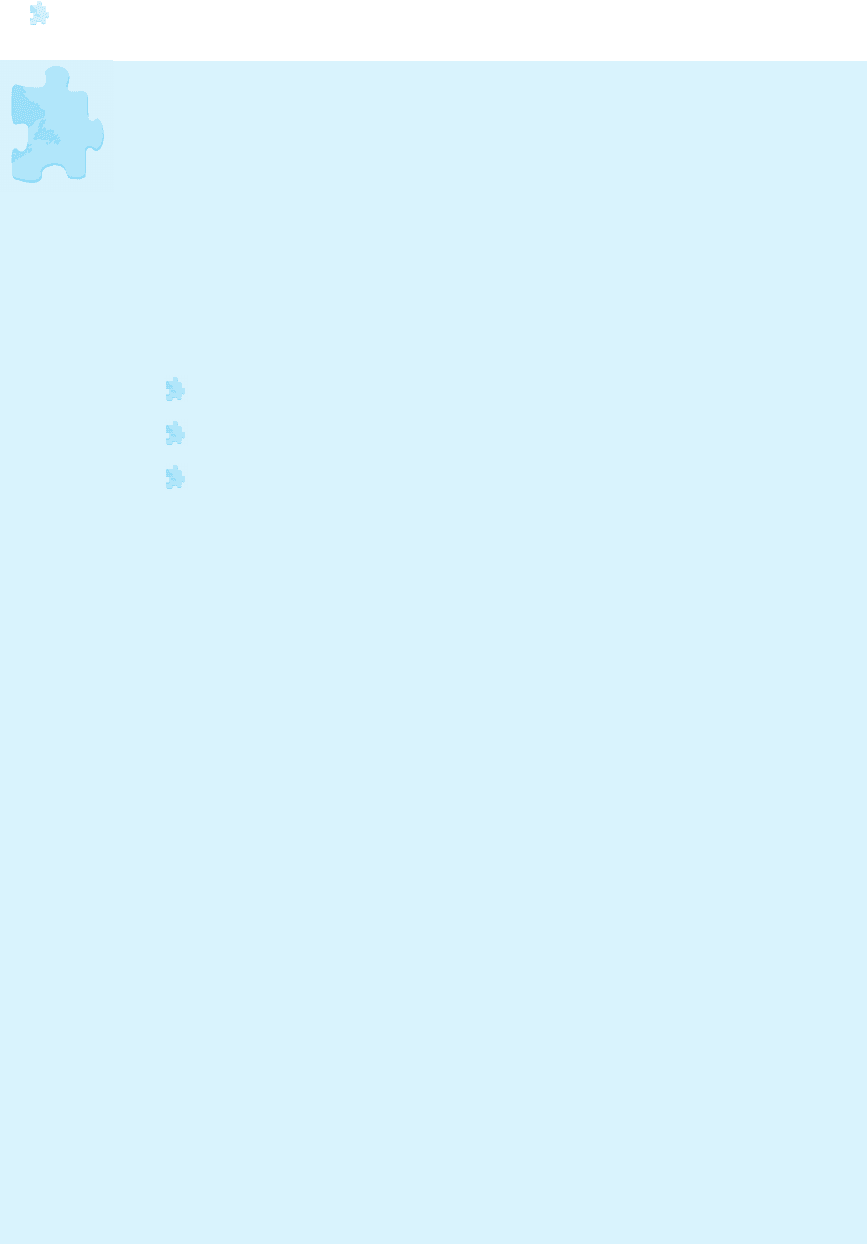

four dimensions of Hofstede (see Figure 2.2).

In practice, the extent to which cultural differences were felt to lead to real

difficulties depended very much on how the alliance evolved over time. Whereas

the cultural difference between the Dutch and the Swedes was the smallest

between the various alliance partners, the negative emotions from the Dutch

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 88

NATIONAL CULTURES AND MANAGEMENT 89

towards the Swedes became stronger and stronger, as parent company Telia

gradually shifted its attention to an alliance with other Nordic providers, and lost

interest in Unisource. The cultural gap between the Dutch and the Spanish, in

contrast, seemed to disappear as the Spanish came to be seen as the more reli-

able alliance partners.

Question

1. Use the emic perspective to reflect on the phenomenon of shifting perceptions

of cultural differences over time as a function of the evolution of the alliance.

Figure 2.2 Cultural differences between the Netherlands, Sweden and Spain (cumulative over four

Hofstede dimensions)

NL

Sweden Spain

75

5528

Case: Management of Phosphate Mining in Senegal

Source: Grisar (1997) and general information on Senegalese phosphate mining

and processing.

T

he Senegalese mining industry is dominated by phosphate mining, and phos-

phate-related exports are a major currency earner for the country. In 1994 a

merger between the Compagnie Senegalaise des Phosphates de Taiba

(CSPT) and the Industries Chimiques du Senegal (ICS) made CSPT/ICS the domi-

nant player in the regional phosphate mining and processing industry. The CSPT,

on which this case focuses, was founded in 1957 with French capital and imported

technology. It started production and export in 1960, the year of Senegal’s inde-

pendence. In 1975 the Senegalese state took a 50 per cent interest in the company’s

shareholdings. In 1980 the process of ‘Senegalization’ of the management of the

company took a new turn when the first Senegalese exploitation manager took

over, and for the first time in history the company had more Senegalese than

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 89

90 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

French managers (27 versus 16). During the 1980s, labour relations and relation-

ships with the unions gradually deteriorated. Concurrently, the company suffered

from declining productivity until its absorption by ICS. A superficial reading of the

history of the firm might conclude from the simultaneity of Senegalization and

decline that the Senegalese managers were less capable than their French prede-

cessors. However, such an attribution would be too easy. Closer inspection shows

that the Senegalese managers were trained by the French, and practised the same

management style as the French. But, paradoxically, what was effective when prac-

tised by the French did not work for their Senegalese successors. Senegalese

employees, looking back at the period when the French managed the company,

expressed positive sentiments (quoted in Grisar, 1997: 235):

‘We used to be like a big family in former times.’

‘Before we were all equal.’

‘You were respected for good work and efforts no matter what position in the

hierarchy you had.’

The perception of equality voiced in these quotes is surprising, as during French

rule there was a very clear-cut hierarchy, the French being the bosses and the

Senegalese the subordinates. When interviewing Senegalese workers about the

conduct of the former French and the present Senegalese managers Grisar (1997:

238) made the striking observation that ‘Senegalese managers lost respect among

workers for the same behaviour for which the French had been respected.’

Apparently what was acceptable, or even laudable when coming from the French,

was interpreted very differently when coming from fellow countrymen. According to

Grisar the key to understanding this paradox is the isolation of the French expatri-

ates in Senegalese society, and their ignorance of caste and class differences and

affiliations, which normally determine an individual’s status in Senegalese society.

Because the French were in a special position, outside the fabric of the networks of

society, Senegalese subordinates tended to accept their decisions as impartial. The

same decisions taken by Senegalese managers, in contrast, were often explained on

the basis of the social relationships (or lack of such) between superior and subordi-

nate. Hence the acceptability of managerial decisions depended on the motives

ascribed to the manager taking the decisions, with systematically different (social)

motives being ascribed to fellow Senegalese than to the French.

Questions:

1. To what extent can the relative failure of Senegalese management at CSPT be

explained by the positions of France and Senegal in Hofstede’s five dimen-

sions of culture (see Table 2.6)?

2. What would you recommend the management of CSPT/ICS do in order to

improve the effectiveness of its management?

MG9353 ch02.qxp 10/3/05 8:35 am Page 90