Carafano James Jay. Waltzing into the Cold War: The Struggle for Occupied Austria

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

exclusively on Soviet intentions. The newly established Department of the

Army (formerly the War Department) began to issue worldwide alerts on the

international communist threat. The preface of one such announcement

stated that these reports were “intended to aid commanders by providing

this type of information on a broad scope so that incidents occurring within

your command may be viewed from their standpoint of greater signifi-

cance.”

34

The imperative became increasing watchfulness of the growing So-

viet menace.

Stalin fueled the Americans’ concerns by promoting policies that were

far from transparent. During the difficult period 1946–49, the enigmatic

and often hostile mask of Soviet Austrian policy was Gen. Vladimir V.

Kurasov, Stalin’s representative to the Allied Council. At forty-nine, Kurasov

did not have the heroic reputation of Tolbukhin or Konev. During the Great

Patriotic War he earned an excellent reputation as a chief of staff. In 1945,

he was appointed chief of administration in the Soviet Group of Forces, East

Germany, then deputy commander in chief of the Central Group of Forces,

and, finally, commander in chief of the Central Group of Forces.

Kurasov’s task was not to make foreign policy but rather to carry out di-

rectives from Moscow. Many leaders were unclear whether their purpose

was to simply protect Soviet interests or intentionally provoke the West. Not

Kurasov. In 1947, he relieved three federal police chiefs in the Soviet zone

because they reportedly had not done enough to purge fascist influences.

Austrian ministers complained to Kurasov. Getting no satisfactory reply they

protested to the other representatives on the Allied Council that the Soviet

action presaged an attempt to completely take over. Other actions proved

equally antagonistic. Kurasov refused to account for the continuing rash of

unexplained kidnappings in the Soviet zone. At the same time, he was

adamant over demands for reparations claims against German assets in Aus-

tria, a contentious issue that had persistently stymied state treaty negotia-

tions. Kurasov’s complaints of slights against the Soviet occupation forces

by Austrians and the other Allied powers were frequent and invective. When

the feisty Migsch delivered a speech critical of the communists and admin-

istration in the Soviet zone, Kurasov protested to Chancellor Leopold Figl

about the “inadmissible and aggressive slander of the Soviet people” and

warned he might have to prevent such things in the future.

35

These encoun-

ters served only to fuel the West’s growing uneasiness over Stalin’s interests

in Austria.

In response, efforts to collect Soviet-related intelligence accelerated. In

1947, USFA established an intelligence section whose primary function was

“to collate, evaluate and interpret all information received pertaining to the

Soviet Army.”

36

The MIS was tasked not only with providing data on issues

88 waltzing into the cold war

related to Austria, but also on matters of strategic interest, including infor-

mation about Soviet atomic programs and potential industrial targets inside

the Soviet Union.

That autumn, responding to the joint chiefs’ apprehensions over West-

ern Europe’s stability and State Department concerns about European eco-

nomic conditions, the intelligence section prepared a report on activities in

the country. The analysis concluded that the Soviet occupation forces’ in-

fluence was “sufficient to deliver Austria into Soviet hands within six

months.”

37

This estimate was one of USFA’s first overt warnings, moving the

Soviets to the front of the pantheon of social, political, and economic ob-

stacles to postwar reconstruction.

In February, 1948, the high commissioner’s monthly report for the first

time singled out Soviet behavior as the root cause for the failure to success-

fully conclude the state treaty. In addition, reports began to focus on the

KPÖ, the Soviet Union, and other Iron Curtain countries as potential mili-

tary threats. In March, 1948, USFA intelligence estimates concluded that al-

though Soviet occupation forces admittedly were understrength, they were

“battle worthy and are capable of and psychologically prepared for offen-

sive military action.”

38

Other reports highlighted armed confrontations be-

tween U.S. and Soviet military personnel, the kidnapping and coercion of

Austrian civilians, reports by Russian deserters of impending attacks, and

subversive activities by the Austrian Communist Party.

39

The preponder-

ance of intelligence suggested that the Soviets had emerged as dangerous and

aggressive agitators determined to extend their hegemony over Austria and

threatening Italy and Germany as well.

In turn, USFA’s findings generated further caution in determining the fu-

ture of the occupation. Charles Ginsburg, a member of the U.S. delegation

at the 1947 Council of Foreign Ministers, concluded—based in part on in-

telligence reports of activities in Austria—that the Soviet Union’s presence

represented a serious threat and made negotiating the state treaty problem-

atic.

40

Future dealings over Austrian affairs had to be tempered with greater

vigilance.

Hitler Revisited

During this period, army intelligence reports also showed an upswing in re-

porting on potential Nazi activity, in particular reflecting concerns about a

rise in anti-Semitic incidents and the impending formation of a right-wing

political party. The renewed interest in denazification had very little to do

with what had once been the army’s core mission. Extremist activity was

now a matter of concern because of its potential impact on the nature of the

largest single industry 89

Soviet threat. Despite Kurasov’s frequent antifascist rhetoric, USFA feared

communists might be secretly recruiting former National Socialists. Military

intelligence officers launched a full investigation into the matter.

41

Alterna-

tively, USFA believed the Soviets were using any signs of right-wing activism

as an excuse to criticize Western occupation forces and the Austrian gov-

ernment for encouraging anticommunist sympathies. Soviet harangues were

launched with an eye toward destabilizing the country and creating condi-

tions for a coup or perhaps direct intervention. Finally, USFA was also con-

cerned that the right-wing movement might threaten the current corporatist

arrangement in the Austrian government, making the country even more

vulnerable to Soviet penetration.

The command adjusted policies accordingly. Scaling back on denazifi-

cation programs in the judiciary and transferring legal authority for most

cases from the military courts to the Austrians was seen as one way to en-

hance the status of the Austrian government and draw it closer to the United

States.

42

United States Forces Austria wanted to appear firmly anti-Nazi on

the surface, while actually placing as little pressure as possible on the Aus-

trian government. At the same time, intelligence specialists and agents were

fervently collecting information on right-wing activity to prevent exploita-

tion of the situation by the Soviet menace.

Concerns over the threat of domination from the Kremlin dovetailed

with thinking in Washington. Lemnitzer observed the changing perceptions

of America’s former ally from Washington, first as a member of the Joint

Strategic Survey Committee at the Pentagon, then as deputy commandant of

the National War College at Fort McNair. In addition to the newspaper

headlines on confrontations with the Soviets in Austria and other countries,

he was privy to the flow of increasingly concerned intelligence reports, all of

which suggested that the Soviet Union had crossed over from being a recal-

citrant partner to a dangerous opponent.

In the summer of 1948, Lemnitzer was dispatched to London on a top-

secret mission that drew heavily on his now considerable experience in

coalition operations and European affairs. He participated in a series of

clandestine meetings with the military committee of the signatories to the

Brussels Treaty which, signed on March 17, established the West Euro-

pean Union. His mission was to determine what assistance its members

would require to defend against a Soviet invasion. Although the United

States was not a member of the treaty group, Lemnitzer was there to

demonstrate U.S. concern and revive the wartime spirit of coalition part-

nership. These efforts and the changing perception of the Soviet role in

Austria would have a dramatic impact on how USFA viewed its mission in

the years ahead.

90 waltzing into the cold war

Fallacy and Fear

Over the course of four years, the Soviets went from representing no threat,

to being a threat, to being the threat. What is most remarkable is that while

USFA’s assessments changed radically from 1945–48, this transformation

had very little to do with the intelligence on hand. A detailed review of the

command’s reports demonstrates conclusively that the United States did not

have the evidence to accurately gauge changes in Soviet behavior. Rather,

USFA reinterpreted available evidence to meet current requirements.

Indeed, the character of raw intelligence information collected during

these years changed little. Throughout this period, the command received

reports on border incidents, KPÖ activity, the kidnapping of Austrian citi-

zens, military training and maneuvers, and economic penetration of the

economy. However, reports that were ignored or explained away in 1945,

were mentioned in 1946, and highlighted as the root of all troubles by 1948.

From the outset, there is little doubt that senior commanders knew full

well about the scope of Soviet misconduct. General Clark described Soviet

behavior during this period as “Russians running around killing, looting,

stealing, raping.”

43

At the time, however, these incidents were interpreted as

unfortunate shortcomings, misunderstandings, or minor irritants. The dif-

ficulties were part of the challenge of working with multinational forces;

they were no more ominous than the problems frequently experienced in

working with the French. Soviet activities were not portrayed as symp-

tomatic of any real security threat to the United States.

By mid-1947, U.S. forces began to highlight the kinds of Soviet and

communist behavior that had been all but ignored in the previous years of

the occupation. In addition, not only were similar kinds of activities being

cited as indicators of a growing danger, but previous acts were resurrected

and reinterpreted as threats as well. One military report cited disputes over

food distribution, disagreements over denazification, Tito’s postwar inva-

sion of Carinthia, disruption of transit to Vienna, and disagreements over

reparations, to portray a pattern of Soviet action consistent with attempting

to exert hegemony over the country. Past intelligence was used to confirm a

deliberate, aggressive strategy in Austria dating back to the earliest days of

the occupation.

44

In the end, it was the identification of the Soviet Union as

a threat that provided mission focus and clarified for USFA’s analysts the am-

biguities in Soviet behavior.

Increasing tensions between East and West, fueled by several dramatic

regional developments, provided further impetus to view events in Austria

as part of an orchestrated campaign of Soviet hostility. On Europe’s periph-

ery, Soviet and U.S. interests clashed in Greece, Turkey, and Iran. In 1947,

largest single industry 91

communist agitation rocked France and Italy. The following year, commu-

nists overthrew the government of Czechoslovakia and Stalin ordered a par-

tial and then total blockade of Germany’s capital, Berlin. In every direction,

USFA saw visible signs of Soviet aggression and assumed it was all part of a

concerted plan that included expanding the Soviet sphere of influence over

both Germany and Austria.

The Search for Secrets

The utility of USFA’s effort in determining the intent behind Kurasov’s rail-

ings and the activities of his troops is questionable. The most recently re-

vealed high-level Soviet policy documents contradict USFA’s intelligence

analysis and suggest that while Stalin sought to consolidate Soviet hegemony

over the European heartland and intended to bargain hard with the West-

ern powers, he did not contemplate overt aggression against his wartime Al-

lies.

45

This handful of documents will certainly not be the last word in un-

covering the history of Soviet intentions. It may be some time before a

sufficiently full accounting of Soviet activities is available to match up side-

by-side with USFA’s intelligence analyses, and thus be able to fully gauge the

accuracy of the command’s assessments. Nevertheless, while historians

await a fuller understanding of the Soviet position, definitive conclusions

can be drawn on the character of the U.S. military effort. United States

Forces Austria did not provide unbiased and critical analysis. Following the

rhythm of habits, the command generated intelligence based on the identi-

fied threat. In turn, USFA’s reporting method justified concerns over Soviet

intentions with a tendency to reinforce existing preconceptions.

Meanwhile, the rapid postwar decline in the quality of military intelli-

gence capabilities at the same time the demands for information and the vol-

ume of reports collected were dramatically increasing seriously exacerbated

the problem. True, much intelligence, particularly information about Aus-

trian domestic politics, was helpful and put to good use. However, in the

larger context of U.S.-Soviet relations at the outbreak of the Cold War, the

worth of USFA’s effort is debatable.

A further difficulty was that this questionable intelligence also under-

mined the military’s traditional approach to coalition operations. American

military leaders knew that the Allies could be difficult, but they always ex-

tended a modicum of trust that served as a basis for negotiation and coop-

eration. In this case, however, adverse intelligence assessments destroyed

any confidence that they had in working with their Soviet counterparts.

Making matters worse, both sides maintained the fiction of cooperation

through occupation machinery that was designed for allies who possessed a

92 waltzing into the cold war

degree of trust and confidence in one another. The Allied Council had few

institutional mechanisms to ensure transparency, such as the joint police pa-

trols in Vienna. Once suspicions grew to unmanageable proportions there

was no means to rebuild a productive relationship or resolve ambiguities

and uncertainties, nothing to break the accelerating cycle of mistrust and

confrontation.

In the period following this breakdown of Allied relations, army intel-

ligence played a significantly less important role in shaping perceptions. As

the Cold War intensified, the United States shifted to other means that could

penetrate behind the Iron Curtain. Initially, signal intelligence assumed

greater importance in collecting information. By 1948, U.S. intelligence op-

eratives were intercepting and reading classified communications from no

less than thirty-nine countries.

46

Meanwhile, with the establishment of the

CIA, that agency gradually assumed primary responsibility for collecting hu-

man intelligence, providing national strategic assessments, and conducting

covert operations. The United States also began to rely more heavily on aerial

reconnaissance and overflights of the Soviet Union. Increasingly national

largest single industry 93

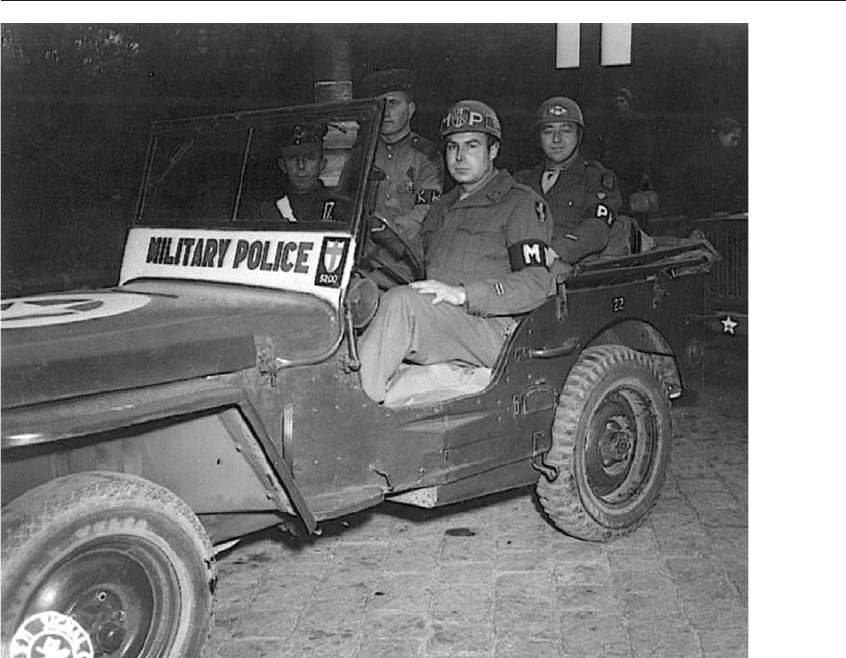

American, British, French, and Soviet military police patrol, Vienna, October 2, 1945.

Courtesy National Archives.

means of strategic and technical intelligence were more valued than the ob-

servations, rumors, and interrogations collected in Vienna.

While Austria’s value as a strategic listening post declined, the impact of

intelligence operations on the future course of the occupation would prove

long lasting. Commanders armed with a fully documented and acknowl-

edged Soviet threat, and foreseeing the prospect of a new European military

alliance supported by the United States, could now make an argument for

rethinking USFA’s purpose, turning the occupation into a real military mis-

sion.

94 waltzing into the cold war

Guarding USFA Headquarters, 1945. Courtesy National Archives.

B

rigadier General Thomas F. Hickey had a warrior’s heart. Born

in Massachusetts in 1898, he enlisted in the army in 1916, and

later received a lieutenant’s commission. Hickey fought in sav-

age battles during the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne campaigns for

which he received a Purple Heart after being wounded in action. During

World War II, Hickey headed to the Pacific in command of the X Corps Ar-

tillery. He later served as corps chief of staff in the Leyte campaign, and then

commanded the 31st Infantry Division Artillery.

Following V-J Day, General Hickey was briefly reassigned to a stateside

post before being sent overseas in 1946 to replace Alfred Gruenther as

USFA’s chief of staff. It was a position he would hold for almost four years.

Before Austria, his career was a long list of schools, conventional military

assignments, and combat. The one thing missing from his résumé, aside

from two years of occupation duty in the Rhineland as a lieutenant after

World War I, was any background in foreign affairs or military government.

Hickey’s limited experience with occupation matters actually made him

a comfortable match for Mark Clark’s replacement, Lt. Gen. Geoffrey

Keyes. Hickey and Keyes represented a generation of leaders least experi-

enced in civil-military affairs. In quieter times this lack of experience might

have mattered little. As the Cold War intensified, however, these men found

themselves at the point of the spear.

Strange Friends

A rapidly deteriorating postwar coalition was not the army’s only obstacle

to providing effective administration. Occupation duties also required

commanders to cooperate with a wide range of federal, international, and

nongovernmental agencies in addressing the complex tasks of reconstruc-

tion. As American concerns rose, the pressure to harness all the instru-

chapter 5

On-the-Job Training

ments available to speed European recovery increased commensurately.

This was no small challenge in Austria’s case because the United States had

not yet developed a long-term strategy. Lacking an overarching strategic

framework to guide their actions, and with no practices, doctrine, or ed-

ucational institutions to develop their cooperative skills, occupation offi-

cials were forced to learn how to integrate the military and civilian efforts

on the job.

Since the army had little practice in operating with other agencies, this

particular rhythm of habit did not bode well for the future. Working with

the UNRRA was an unqualified disaster. The newly established civilian

agency was neither properly organized nor equipped for the mission of car-

ing for 1.5 million refugees and displaced persons. Even UNRRA officials

admitted there were serious problems and that a “thorough house cleaning”

was required.

1

United States Forces Austria personnel had little patience for

the civilian organization’s ineffectual first efforts. One official complained

that the UNRRA set back the country’s recovery by six months. Nor was the

UNRRA the only agency that had difficulty working with the army. “The

military authorities,” an investigative report concluded, “have shown con-

siderable resistance to the entrance of voluntary agency representatives, no

matter how qualified they might be.”

2

On the other hand, the two most important players, the army and the

State Department, initially appeared to function together quite well, follow-

ing wartime precedents with the army in the lead and State supporting.

Much of the credit belonged to the tireless efforts of John Erhardt. Erhardt

had far more experience in the issues surrounding the occupation than the

senior military leaders for whom he worked. A career foreign service officer

with much experience in European affairs, he had served as consul general

in Hamburg from 1933–37. Erhardt had also worked extensively with the

State Department’s Postwar Programs Committee.

By all accounts, Erhardt, Clark, and their people functioned well to-

gether. In fact, Clark, who was merciless in his treatment of USFA’s military

staff, readily accepted his political adviser’s suggestions and opinions.

Eleanor Lansing Dulles, an economic analyst in the legation, recalled that

for the most part Erhardt “handled Mark Clark quite well. Once in while

he would say ‘Mark Clark you are kind of an idiot you know, you shouldn’t

do that,’ but by and large he went along with Mark Clark.”

3

Another offi-

cial called Austria a “model of military and civilian cooperation.”

4

Despite the reputation for close collaboration and the fact that the State

Department had no objection to Clark being followed by another military

commissioner, his departure in May, 1947, revealed symptoms of a rift.

Clark’s farewell speech included a strong and unambiguous statement of

96 waltzing into the cold war

support for Austria. The State Department complained that the pronounce-

ment had not been properly cleared with Washington. Moreover, the gen-

eral’s remarks suggested an unrestricted, unending commitment to the

country, while in fact, the United States had not settled on its future course

in the treaty negotiations.

5

Responsibility for implementing whatever long-term strategy did

evolve fell to Clark’s successor. If any figure comes to mind in association

with the occupation it is the tall, flamboyant Mark Clark. Time would prove,

however, that Keyes, not Clark, was without question the single most influ-

ential individual shaping U.S. policy toward Austria.

In many respects, Keyes was typical of the senior leaders the army pro-

duced during this period: unlikely candidates to assume key political-

military roles in postwar Europe. Born in Fort Bayard, New Mexico, and ed-

ucated at West Point, Keyes had been posted outside the United States only

three times. He participated in the punitive expedition into Mexico in 1916,

served in the Panama Canal Zone from 1927–30, and attended the École

Supérieur de Guerre in Paris in 1933.

Like Hickey, Keyes was a fighter. He attended the Army War College in

on-the-job training 97

American military government officials receiving a complaint, 1945. Courtesy National

Archives.