Carafano James Jay. Waltzing into the Cold War: The Struggle for Occupied Austria

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A

t 5:30

P

.

M

. on September 19, 1950, Gen. Mark Wayne Clark re-

turned to Salzburg. He was a man with a mission. As chief of the

Army Field Forces, his responsibilities included training and

equipping troops in the United States, as well as inspecting the readiness of

overseas commands. The Korean War had given new importance to his as-

signment. A counterattack employing the last of the U.S. strategic ground

force reserve had taken place at the port of Inchon outside the capital of

Seoul only days before his arrival. It was still unclear if the bold maneuver,

an amphibious landing far behind enemy lines, would prove successful.

There were other dangers as well. The United States was not only concerned

about the fighting in Asia. The JCS remained fearful that the Soviets would

use the war as a diversion, a precursor to aggression in Western Europe.

Clark was no stranger to the dangers of war. Born to a military family

stationed in New York, Clark had followed his father into the service. Com-

missioned as an infantry officer after graduating from West Point in 1917,

he joined the American Expeditionary Force in France. He saw only a little

action before being wounded early in the summer of 1918 while leading a

company of the 11th Infantry Regiment in the Vosges Mountains. Clark

passed-up an opportunity to serve with the occupation forces in order to

seek a real command assignment elsewhere. During the interwar years he

gained a reputation as a demanding and energetic leader. Both Marshall and

Eisenhower thought highly of him, and Clark went on to become the most

well known, and perhaps most controversial, combat leader in the Mediter-

ranean—a man destined for continued high-level leadership positions after

the war.

His wartime record and postwar career made Clark a prominent

public figure. After his experiences in Austria, Clark became a rabid anti-

communist, preaching frequently about the need to meet force with force

wherever American and Soviet interests clashed. His tour of USFA would

chapter 6

From Occupiers to

Warriors

give him an opportunity to see how his old command was standing up to

this new challenge.

Transformation

A wave of defense, political, social, economic, and racial issues attended the

command’s transition from occupiers to warriors. The response to these

challenges further fueled the momentum for militarizing the occupation,

tested the Americans’ relationship with the Austrians, and sharpened the

confrontation with the Soviet Union.

Initially, U.S. forces had scant means and little incentive to improve

their military preparedness. As a result of the rapid demobilization, troop

readiness plummeted drastically. United States Forces Austria was chroni-

cally short of people, turnover was constant, and there were limited oppor-

tunities and resources for conducting combat training. Nevertheless, the oc-

cupation forces proved more than adequate to deal with the security aspects

of implementing the disease and unrest formula. There were no official

threats meriting an armed response.

In the wake of the Czech coup, Keyes began a concerted effort to re-

structure USFA into a combat command. He ordered the troops put through

an expanded regimen of training. In 1949, he disbanded the constabulary

force and reformed it into conventional combat units. All of the combat

forces were grouped under the Tactical Command, which was headed by a

brigadier general, and directed to conduct winter and mountain warfare ex-

ercises. Tactical Command also conducted joint training with British,

French, and U.S. troops in Germany, although these contingents had little

to offer.

1

There were only a handful of divisions in Germany. The British

had seventy-five hundred troops in Austria, including three thousand com-

bat soldiers organized into four infantry battalions. These troops were so in-

volved in occupation duties that they had no opportunity for military train-

ing. The French had sixty-nine hundred soldiers grouped into battalions of

infantry, five troops of mechanized cavalry, and two companies of engineers.

They had conducted some training, but were prepared only to defend key

terrain in their zone.

2

Pass in Review

As for the Americans, when Clark arrived he saw how dramatically things

had changed since his departure. The Keyes-Erhardt war had flared and sub-

sided. Keyes was preparing to leave, and Erhardt had been appointed am-

bassador to South Africa. Meanwhile, Walter Donnelly, a career diplomat

from occupiers to warriors 119

whose greatest expertise was in Latin American affairs, was slated to take

over as the first U.S. civilian high commissioner for Austria, and Lt. Gen.

Leroy Stafford Irwin had been tapped to succeed Keyes as the USFA com-

mander.

Irwin, by training and experience, was more of the Keyes mold. Born in

1898 and graduating from West Point in 1915, he, like Keyes, served in the

Punitive Expedition in Mexico. Missing out on combat after being assigned

as an instructor during World War I, Irwin went on to command the 5th In-

fantry Division in World War II. Unlike Keyes, Irwin would enjoy good re-

lations with his State Department counterpart. Confrontations subsided in

part because personalities were changing, but also because with negligible

progress on the treaty, the State Department could offer little objection to

sharpening military preparedness.

United States Forces Austria’s transformation impressed Clark. His in-

spection team rated the quality of training as excellent. On the other hand,

despite the progress and positive developments, several areas of concern re-

mained. The command lacked many essentials that prevented it from acting

realistically in the manner of a true fighting force. The most serious short-

fall was a lack of people. A moratorium on personnel transfers as a result of

the Korean War temporarily abated the problem of rapid personnel

turnover, but the command still suffered from significant manpower short-

ages. United States Forces Austria was short a hundred officers and a thou-

sand sergeants.

Equipment was another problem. The command had no gear for moun-

tain operations and no field hospital. Most vehicles were rickety holdovers

from the European campaign. The command lacked long-distance radio

communications to cover the wide frontages envisioned in the war plans.

The troops had no antitank weapons. All these shortfalls would prove sig-

nificant if U.S. forces were called upon to conduct a fighting withdrawal in

the face of superior Soviet forces.

Even worse, the command had no air support and no contingency plans

for employing air cover. The troops had not even conducted training in air-

ground operations. War plans envisioned that the U.S. Sixth Fleet would

provide air support, but the fleet had not been formally tasked. Even if the

navy had been assigned the mission, it would have been impossible to exe-

cute. The ground troops had no tactical air support control parties, teams

that had the equipment and expertise to coordinate air attacks. Nor did the

fleet have aerial reconnaissance assets, an air warning system, tactical air de-

fense, navigational aids, or air-to-ground radios. Making matters even more

anxious, neither the French nor the British occupation troops had any

planes.

3

This was deadly serious. A withdrawal under pressure, without air

120 waltzing into the cold war

attacks to slow the enemy or protect friendly troops from enemy planes,

would have been a desperate venture.

The logistical situation was also a nightmare. Most personnel shortages

were in support units. Supply and maintenance operations relied heavily on

civilian employees. They were dependable in peacetime, but they could not

be counted on in war. Also troublesome was the fact that the supply line ran

through Germany. United States Forces Austria assumed this would be

quickly cut by a Soviet offensive. Wartime maneuvers would require a dif-

ferent route. Before leaving Italy, occupation troops established the infra-

structure for a wartime supply line that could be reoccupied in the event of

an emergency. This alternative proved less than ideal, running from the port

of Leghorn, Italy, through Verona and the Brenner Pass to the Camp Drum

storage depot at Innsbruck, and then to the troops in Salzburg—a torturous,

mountainous route of over three hundred miles. For the most part, supply

points were exposed, highly vulnerable to attack, and not well positioned to

support the tactical movement of combat troops to either link up with forces

in Germany or fall back toward the Italian border.

4

Over the next three years, as USFA pushed for a more prominent role in

the defense of Europe, the state of forces continued to improve. Army Field

from occupiers to warriors 121

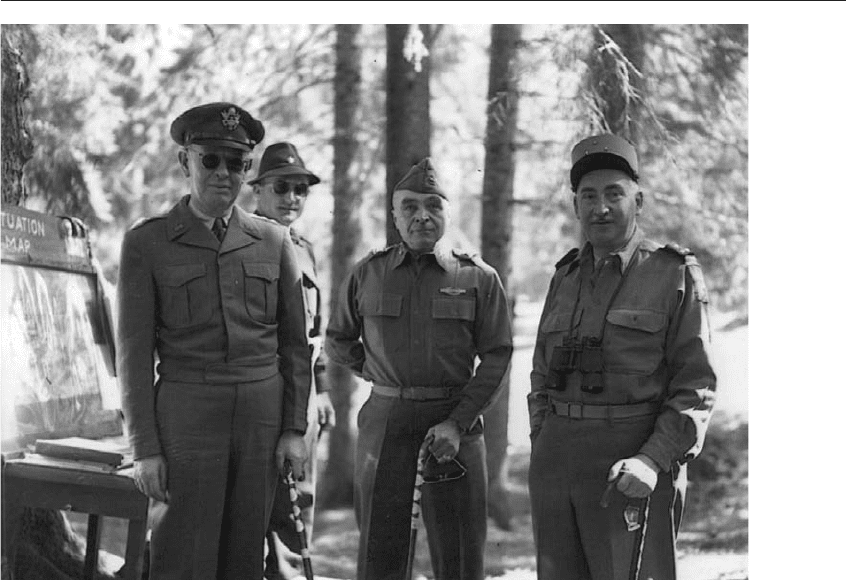

Lieutenant General Leroy Irwin (left) meets with French officials during Operation Mule

Train, a joint U.S.-France training exercise, September 11, 1951. Courtesy National Archives.

Forces command inspections noted steady progress. The United States

opened negotiations with the Italians to make USFA’s new supply line func-

tional. The 7617th Support Command set up port operations in Leghorn,

and the whole route became operational in 1951. By 1952, critical depots

had been relocated and for the most part the supply lines matched the

planned routes for operations. A year later, combat stocks were reported to

be in relatively good shape. The command had a sixty-day level of preposi-

tioned ammunition in the hands of combat units and more was stored along

the Innsbruck–Brenner Pass–Po Valley line. The depot at Leghorn included

ammunition reserves for both USFA and forces in Trieste.

5

Other shortfalls suggested there was still a long way to go, however.

Limitations were significant and there is serious doubt that any military ef-

fort would have actually succeeded. Air support was a case in point. United

States Forces Austria eventually worked out some of the most pressing prob-

lems by organizing its own air support platoon to provide air-ground coor-

dination with radios borrowed from the navy, and entering into local train-

ing agreements with the Twelfth Air Force and Sixth Fleet. Still, air-ground

support was woefully inadequate. Peacetime arrangements with other com-

mands could not be counted on in wartime, and reliable air-ground support

and aerial photoreconnaissance for the command was never considered

adequate.

6

Nevertheless, despite the army’s limited resources, ground operations

showed steady improvement. In 1951, the command conducted Exercise

Rebound, a joint training maneuver with troops from 351st Infantry Regi-

ment in Trieste, and Operation Mule Train, a joint training exercise with

French troops. In November, 1952, Exercise Frosty employed USFA’s 350th

Infantry Regiment to defend mountain passes. Two hundred soldiers re-

ceived mountain warfare training at Camp Carson, Colorado, before de-

ploying to USFA. The command also set up its own mountain training

school and sent soldiers to a French military alpine school. The regiment

then organized special mountain warfare platoons made up of the most

physically fit men who had received the additional training. These units

were armed with light weapons and minimal equipment so they could more

easily negotiate the key terrain dominating likely invasion routes.

7

When Brig. Gen. Paul Freeman was appointed commander of Tactical

Command, he found it well prepared to execute wartime operations. “We

had a secret mission which was to protect the right flank or the Southern

flank of the Seventh Army [Germany] and we had battlefield positions ex-

tending from Degensburg [Regensburg?], I believe it was, in Germany all the

way down to Salz-Kammergut,” he recalled. “We were to hold those moun-

tain passes and delay into Italy.”

8

United States Forces Austria was ready for

122 waltzing into the cold war

from occupiers to warriors 123

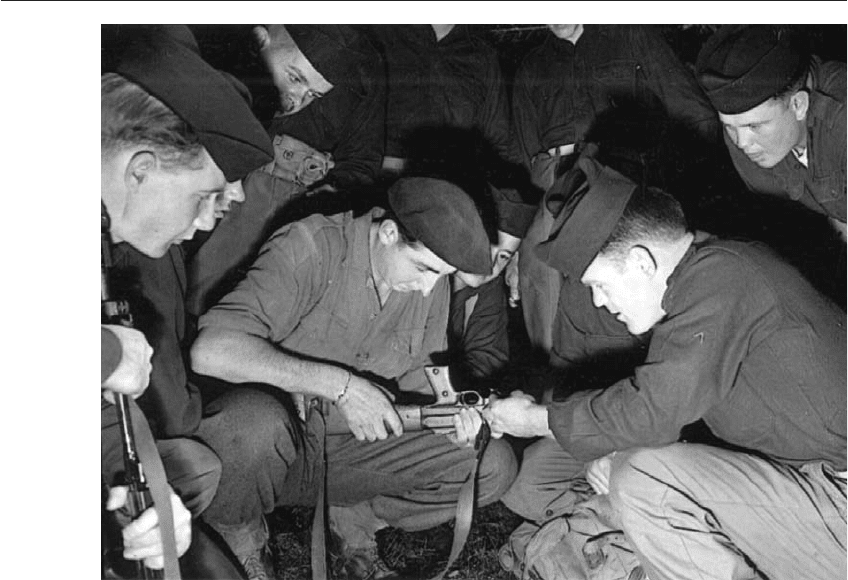

American troops dressed as the “enemy” during Exercise Frosty. Courtesy National Archives.

war. Over a span of five years the command had been remade from an oc-

cupying army into a small but credible combat force.

Soldiers and Civilians

The transformation from occupiers to warriors did not go unobserved. The

increased emphasis on readiness did not escape the notice of the civilian

Austrian press, though USFA did not anticipate its activities would cause

much concern. After the first harrowing years of dealing with every form of

privation from food and housing shortages to violent crime and rioting, con-

ditions seemed to improve, thus allaying the most serious fears. Comman-

ders were content with the state of cooperation. Official Austrian sources

were equally positive. Local police provided periodic reports on the state of

local security and public safety, and up to 1950 they generally suggested that

collaboration with American occupation forces was satisfactory.

9

The outbreak of the Korean War, followed by a violent wave of strikes

fanned by the KPÖ that lasted from late September to mid-October, dra-

matically changed the Austrians’ thoughts of the future. Before Korea there

had been vegetables and meat in stores. There was coal to burn. Men had

gone back to work. The outbreak of war changed everything, drying up

supplies of raw materials and fueling inflation. Fear of being caught in a

battle between GIs and Russians swelled.

On February 10, 1951, Donnelly wrote, “Feeling here is that pressure

for treaty and withdrawal has noticeably eased since Korea.”

10

The presence

of U.S. troops, Donnelly argued, was reassuring to the man on the street.

The Austrians knew they had not been abandoned. But in truth, Donnelly’s

assessment did not grasp the depth of unease in the nation. Complaints and

fears about the occupation were persistent and endemic in the period fol-

lowing the tumultuous summer and autumn events of 1950.

Even Donnelly acknowledged that one of the major issues preventing

harmonious relations was the cost of the occupation. The Allies had agreed

from the outset that the Austrians should house their troops and pay the cost

of maintaining the occupation forces. The burden was one the Austrian gov-

ernment did not bear silently. In 1947, the United States, responding to Aus-

trian complaints, assumed its own occupation costs. Donnelly contended

that if the British and French joined the Americans they could further dis-

tinguish their efforts from those of the Soviets. But the British and French,

facing fierce pressure to control defense spending, wanted to raise Austrian

payments. The British believed that increased occupation costs would not be

124 waltzing into the cold war

American and French troops conducting joint training in the Austrian Alps, September 7,

1951. Courtesy National Archives.

intolerable for Austria and would still be smaller than the amount other

Western countries were devoting to defense.

11

The best of all possible

worlds, they argued, would be to figure out how to raise expenses while

camouflaging the increases to make the public expenditures appear lower

than those going to the Soviets. They dithered over the issue for the next two

years, losing any potential propaganda advantage when the Soviets dropped

the demand for occupation payments months before the cash-strapped

British and French ended the practice. What is more, Donnelly’s assessment

was disingenuous. Rather than representing the only problem, the issue of

occupation costs was a reflection of the growing friction between occu-

piers and occupied. The United States, of course, came in for its fair share of

criticism.

The 1952 Austrian film 1 April 2000, directed by Wolfgang Lieben-

einer, was a stinging reminder of how Austrians viewed the Americans.

While the revival of the film industry was a sign of returning normalcy, the

subject of this movie was telling. The setting is nearly half a century in the

future. After 2,859 unsuccessful negotiating sessions, the four Allies—

portrayed as doddering, white-bearded old men—still preside over the oc-

cupation. A frustrated Austrian president declares the nation’s indepen-

dence, only to have the “World Union” proclaim it is a menace to global

peace. Austria gets a brief reprieve when the union fires its secret weapon at

Australia by mistake. While koala bears cower, a delegation is dispatched to

Vienna, where the president is put on trial by the world government.

Although billed as a musical comedy and science fiction epic complete

with dancing and spaceships, the picture’s antioccupation sentiment is thinly

disguised. The United States appears just as much at fault for Austria’s

troubles and as oblivious to the people’s sentiments as the other occupying

powers. For their part, the Austrians are a happy, singing, pastoral people.

The streets of Vienna are pristine, swept clean of wartime destruction. Ev-

ery scene is bright and sun-filled, far removed from the dark, shadowy im-

ages of Orson Welles in The Third Man. In Liebeneiner’s film, Austria is a

country that does not deserve to be occupied.

Jim Crow

The tension between Austrians and Americans was nowhere more apparent

than over the issue of race. In the summer of 1952, a local newspaper re-

ported that two black soldiers had attacked three Swedish tourists. An edi-

torial in the Salzburger Nachrichten declared: “We abstain from describing

what would happen for instance in the Southern states of the USA to such

colored rowdies. But we have a good right to demand that the guardians of

from occupiers to warriors 125

our liberty protect at least our foreign guests. When the U.S. Army cannot

forego using Negro soldiers, and said Negro soldiers are unable to give up

their Congo-mentality, the uniformed highwaymen should not be let loose

anywhere.... Our foreign guests come to Salzburg in good faith but not to

find new Africa here!”

12

Donnelly and Irwin complained bitterly about such

reporting, but sensational racial comments continued to pop up in the Aus-

trian papers. The Salzburger Volksblatt published an open letter complain-

ing about the behavior of U.S. troops. The communist paper Der Abend

protested that American occupation forces treated Austrian civilian em-

ployees like “Negroes” with low pay and unfair labor laws.

On July 25, Donnelly met with a group of Salzburg newspapermen in

an attempt to stem the wave of critical articles spotlighting incidents involv-

ing black soldiers. One editor suggested the troops’ behavior was the result

of bringing black soldiers with “a social manner more suggestive of primi-

tive [i.e., African] origins” into the more sophisticated European setting.

13

Donnelly was flabbergasted. The meeting ended in an uproar, and the press

continued to pillory the behavior of occupation troops at every opportunity.

That the army often appeared inconsistent in its attitude toward race

only complicated the Austrian response. The use of Negro manpower in the

postwar military establishment was a contentious issue that extended back

to problems encountered during World War II. During the war, blacks were

assigned to segregated commands, although the pressing requirement for

infantry forced some frontline units to integrate during the closing year of

the war in Europe. One battalion commander, voicing a common opinion

held by white leaders, said, “The discipline among colored troops was de-

plorable.” The approach to the colored problem was wrong, he argued, as

long as colored soldiers were banded together in segregated units, where

they were able to evade discipline on the grounds that they were being

picked on because of their color. If they had been put in white units in the

proper proportion from the beginning, they would have had to stand up and

compare themselves with the white soldiers. Finally, he added, “probably the

colored people were not advanced enough for this treatment [assignment to

integrated units], but if that is the case they should have been given a special

uniform and used as service troops.”

14

Official army policy reached similar conclusions. Black troops had limited

utility and required special handling. When the War Department polled army

commands on the future employment of black soldiers one commander rec-

ommended: “units composed of Negroes should be stationed within the con-

tinental limits of the United States so as to ensure that there will be an adequate

Negro population close by to provide necessary social life for the troops and to

ensure that causes of racial friction in the locality will be at a minimum.”

15

126 waltzing into the cold war

On October 1, 1945, Marshall appointed a board under Lt. Gen. Alvan

C. Gillem Jr. to develop a policy for employing blacks in the postwar army.

The Gillem Board concluded that blacks should only be stationed outside

the United States “on the basis of military necessity and in the interests of

national security.”

16

The army argued that if blacks proliferated throughout

the force, racial tensions within the military and in civilian communities at

home and overseas would seriously detract from military efficiency.

Europe was a special problem. Rapid demobilization, coupled with

high recruitment and retention among blacks, caused the percentage of seg-

regated units in Europe to increase rapidly after 1946. The army responded

with a deliberate plan to thin the ranks of such units.

17

Although blacks had been a prominent part of the force in Europe, they

represented, in many respects, an invisible arm of the occupation. There

were no blacks in military government. The army concluded that because of

the Germanic peoples’ views toward race it would be detrimental to assign

Negro personnel to the constabulary.

18

In July, 1946, the Negro Newspaper

Publishers Association, reporting on conditions in Europe, informed the

War Department that, “the very people whom the Army of Occupation seeks

to democratize are aware of the Army’s policy of separation of Negro and

white, and they, both our allies and the natives of occupied countries, ques-

tion us strongly for seeking to teach what we fail to practice, both at home

and abroad.”

19

The report had a point. Army racial policies ignored issues of tolerance,

fairness, equal opportunity, and equality before the rule of law—exactly the

kinds of values that should have been emphasized in reconstructing civil so-

ciety in a country whose former government had built its foundations on

policies suffused with racial hatred. This was typical of the American ef-

forts. Few of its measures to influence social, political, and cultural devel-

opments penetrated to the taproot of the problems of building a tolerant

civil society. The United States worked for the creation of a democratic, con-

sumer-oriented, capitalist state, but completely ignored such issues as race

and ethnicity. United States Forces Austria’s social focus was on denazifica-

tion efforts, and later offering support for anticommunist groups.

In trying to ignore the race issue, the army was again falling back on its

rhythm of habits and wartime experiences. Commanders had been brought

up in a tradition that argued integration detracted from military effective-

ness, a conclusion reinforced by all of the military’s internal reports and

studies since World War I. In addition, despite the fine combat record of

some segregated commands, the army viewed black units as a liability.

Much was made of reports on race conflict, riots, higher venereal disease

rates, and poor discipline at posts in the United States, North Africa, and the

from occupiers to warriors 127