Carafano James Jay. Waltzing into the Cold War: The Struggle for Occupied Austria

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1937, then, after a Washington assignment, reported to the newly formed

2d Armored division at Fort Benning, Georgia, where he served under

George Patton. An early pioneer in the Armored Force, Keyes briefly com-

manded the 9th Armored Division from June–September, 1942. Promoted

to major general, he again served under Patton in North Africa and Sicily as

deputy I Armored Corps commander. Keyes later led the U.S. II Corps in

Italy. After breaking through the Gothic Line, his corps was attached to the

British Eighth Army and remained astride the Yugoslav border until the end

of the war. In July, 1945, the headquarters moved to Salzburg where it was

inactivated. Keyes remained in Europe, however, and commanded the U.S.

Seventh, and later Third, Armies.

The general’s expertise in political-military affairs was largely confined

to his wartime service: negotiating an armistice with French commanders in

North Africa, facing off against Tito’s troops, and dealing with the initial

occupation of Germany. Keyes’s greatest asset was that he gained the com-

plete trust and confidence of senior military leaders under whom he served,

including Marshall, Patton, Bradley, Eisenhower, and Clark. With the ex-

ception of Marshall, these men were all Keyes’s contemporaries, and each

considered him an intelligent, competent, courageous, and dependable man.

98 waltzing into the cold war

The first meeting of the Allied Council, September 11, 1945. Pictured (left to right) are Maj.

Gen. Alfred Gruenther, Gen. Mark Clark, and John Erhardt. Courtesy National Archives.

Before being assigned to Austria, Eisenhower briefly considered appointing

him to head the Military Advisory Group in China.

Keyes was part of the second generation of occupation commanders.

The first—Clark, Eisenhower, and MacArthur—had been chosen for the

prestige and authority they brought to the task. In contrast, Keyes repre-

sented a new cohort: deserving fellow officers who, though they would

probably never be elevated to four-star rank, deserved to be retained, pro-

moted, and rewarded with a high-profile caretaker job. Thus, while many

of his contemporaries were being shunted off into retirement, Keyes pinned

on a third star.

As for the trials of occupation duty, Keyes’s minimal on-the-job train-

ing in political-military affairs would have to suffice. Austria was not meant

to be a difficult assignment. Although relations with the Soviets had been

contentious, at the time Keyes assumed command many officials believed

the approval of a state treaty was imminent, despite Moscow’s intransigence.

The gathering of foreign ministers in Moscow in March, 1947, had failed to

produce an agreement, but there was still hope that progress might be made

at the next conference scheduled for November. In the end, Keyes might

on-the-job training 99

Lieutenant General Sir Richard McCreery (center) at the Allied Council, December 7, 1945.

Courtesy National Archives.

prove to be nothing more than a temporary commander responsible for the

final withdrawal of U.S. troops.

At the Crossroads

Absent a treaty, however, there still were significant issues at hand. Occu-

pation policy was at a crossroads. The Austrian government wanted the

United States to begin troop withdrawals even in the absence of an approved

settlement, arguing that withdrawal would give them greater flexibility in

dealing with the Soviets over the contentious issues delaying final treaty ne-

gotiations. The legation wanted to consider the proposal, but Keyes rejected

the idea outright. He especially resented the fact that State Department rep-

resentatives had contradicted him. Their approach, Hickey reported, is “to

support the political advisor’s theory that the High Commissioner is just a

figurehead.” The political adviser, he complained, had fallen for the Aus-

trian line that the whole idea was “get the Army out and things will be easy

in Austria.”

6

Keyes was convinced that the Soviets intended to use Austria as a spring-

board for further incursions into Western Europe. His mistrust of the

100 waltzing into the cold war

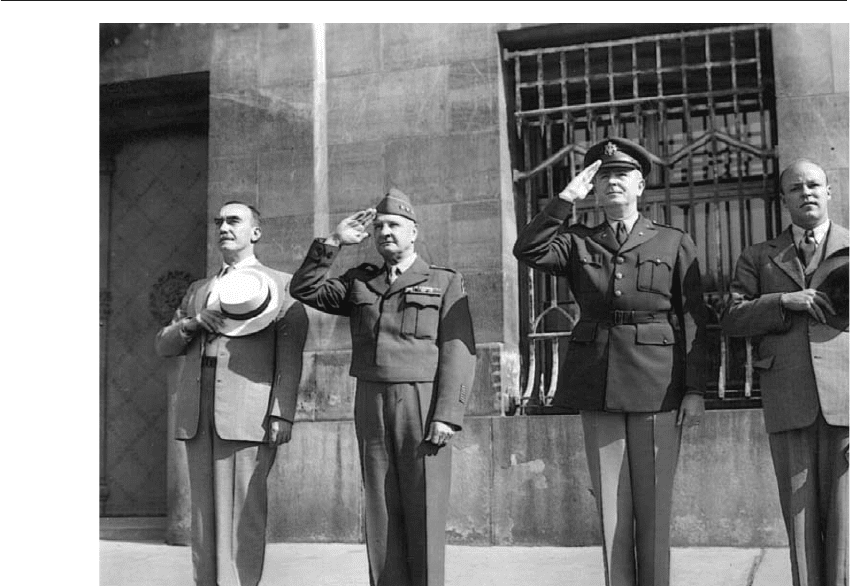

Lieutenant Generals Geoffrey Keyes (left) and Albert Wedemeyer reviewing troops from

350th Infantry Regiment, July 4, 1948. Courtesy National Archives.

Russians was well known. Suspecting a communist-inspired attempt to em-

barrass him the first day on the job, he had ordered extra security measures.

Keyes soon found himself in the midst of a general strike that led to an un-

precedented fourteen days of riots in his first month of command, leaving

the general believing that the communists had planned a putsch and deeply

suspicious that the Soviets were behind it all.

7

The general’s frustration was heightened by Washington’s failure to

provide overarching guidance for the occupation. Military planning, so fun-

damental in the army’s approach to fulfilling its responsibilities, required

clear, decisive, and obtainable objectives, and objectives were derived from

the ends, ways, and means prescribed by strategy and national policy. How-

ever, other than the Moscow Declaration, whose main objective, the de-

struction of Hitler’s regime, had, in fact, already been achieved, the United

States lacked a coherent, comprehensive statement of how it intended to deal

with Austria. Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer, the army’s deputy

chief of staff for operations, summed up the military’s dissatisfaction in a

meeting of the Committee on National Security Organization on Septem-

ber 10, 1948: “Our position of world leadership today makes the necessity

for firm policy on our part even more pronounced than in the past. There is

a serious dearth of national policy now, although the military services and

the State Department are getting much closer together than they have been.

The military services are not asking to determine national policy but only to

be told what it is so that they may more effectively support it.”

8

With respect

to Austria, Keyes’s assessment was even more critical. He considered

army–State Department cooperation a complete failure and the lack of

strategic guidance crippling.

Austria, Keyes believed with all his heart, was a key piece in an emerg-

ing geostrategic confrontation between East and West. Although the coun-

try had never figured prominently in strategic planning either during or

after the war, Keyes believed it would be the linchpin for holding back

communism. For this, he could draw liberally on the voluminous intelli-

gence reports being generated by the USFA staff. Completing the state treaty

was a secondary concern. Austria should not be free until it could resist So-

viet influence. Hickey summed up his commander’s position this way: “It

must not be overlooked from the political standpoint that anti-Communist

forces are not necessarily strengthened by the sovereign state of Austria.”

9

Keyes concluded that U.S. forces should remain until four conditions were

met: a plan to ensure economic independence was in place; an Austrian se-

curity force had been created to insure the country’s territorial and political

integrity; the state treaty was completed; and it was agreed all occupation

forces would be simultaneously and expeditiously withdrawn. He proposed

on-the-job training 101

a two-tracked approach involving a combination of economic assistance

and military aid to accomplish these goals.

10

Keyes envisioned an economic scheme that would piggyback off the

newly announced Marshall Plan. Shortly after his appointment as secretary

of state, on June 5, 1947, Marshall announced in a speech at Harvard Uni-

versity the creation of what would become the European Recovery Pro-

gram. Keyes argued that the initiative could be used to ensure Austrian in-

dependence and fight off Soviet influence.

11

In October, he formally

proposed a neutralization plan for Austria, an economic assistance package

that would neutralize Soviet economic and political penetration of the Aus-

trian economy. His plan, first proposed by Eleanor Lansing Dulles, a mem-

ber of Erhardt’s staff, included specific objectives far over and above the

provisions of the European Recovery Program. Keyes wanted funds for in-

dustrialization and other investments to jump-start the Austrian economy.

Rather than simply being used to strengthen the Western democracies, the

general envisioned the program as a weapon for rolling back Soviet power.

The neutralization plan called for undermining the viability of Soviet-

controlled industries, strangling them by reducing their access to rolling

stock, energy, and raw materials, and boycotting products. Keyes warned

that without this virtual declaration of economic warfare, the country

would easily succumb to Soviet economic domination after the withdrawal

of American troops.

The general also believed that physical protection was equally impor-

tant. Thanks to demobilization and denazification Austria had no military

capability. The presence of U.S., British, and French forces was the only ob-

stacle blocking more aggressive Soviet action. Keyes feared what the British

called the “gap period,” the time after the approval of the state treaty be-

tween when the occupation forces withdrew and the country set up its own

defense forces. As the 1947 riots demonstrated, a government without the

benefit of armed troops would be at Moscow’s mercy. However, in arguing

for maintaining troops in Austria, Keyes had to balance his desires with the

stark realities of U.S. demobilization and the apprehensions of the Austrian

government. After the rapid drawdown following World War II, occupation

duties strained the army’s few resources and manpower. Keyes had only one

combat regiment at his disposal. Still, while even these limited forces were

becoming tiresome to the Austrians, the general rejected the notion that any

troops could be safely withdrawn.

As confrontations with the Soviets exacerbated poor relations between

the superpowers, Keyes’s confrontational approach seemed to dovetail well

with America’s emerging policy of containment, a gradually growing com-

mitment to block any expansion of communist power. In addition to clashes

102 waltzing into the cold war

over Greece, Iran, Turkey, and Germany, the United States and the Soviet

Union became engaged in quasi-economic combat. The Soviets refused to

participate in the Economic Recovery Program, and Stalin tightened his con-

trol over the Eastern bloc, preventing local governments in the Soviet occu-

pation zones in Germany and other East European countries from consid-

ering the American offer of economic aid. Meanwhile, Keyes continued to

pepper Washington with assessments demonstrating how conditions in Aus-

tria fit clearly into the overall Soviet threat to Europe and required a deter-

mined a response. United States Forces Austria had identified four thousand

agents in the Western zones working to expand Soviet influence. There was

a legal, well-organized, and disciplined Communist Party, 150,000 strong

and responsible, Keyes believed, directly to the Kremlin.

12

Not only did the

USFA commander paint a troubled future for Austria, he also passionately

held that the country represented an important strategic asset that should

not be readily given up. Keyes stressed the benefits of continued occupation

in the event of hostilities, not only as an extension of the defense of Ger-

many, but also for its own positional advantages.

Advocacy for more aggressive measures received a considerable boost

in February, 1948, on a damp, cold Saturday morning in Prague as snow

dusted the statue of Jan Huss in the old town square. Despite the inhos-

pitable weather, people gathered around the statue—first a few, then a rush,

a mob screaming for the government ministers to step down. By Monday,

February 23, rough men wearing blue workers’ jackets and red armbands

had surrounded the U.S. embassy, and it was clear by midweek that Pres.

Edvard Benes’s government was in trouble. Forced to accept the resignation

of his ministers and their replacement by members of the Communist Party,

Benes effectively ceded all control of the government. The communists

called it Vitezny unor (Victorious February). In the West, they called it a

coup.

To Keyes, the putsch in Czechoslovakia and the establishment of a So-

viet client regime demonstrated that Stalin could not be trusted. Molotov’s

wrangling over the state treaty was only buying time until the communists

figured out how to take over completely.

13

When the Allies prepared to re-

sume negotiations later that year, Keyes was a forceful voice. Even Erhardt,

in the wake of the Czechoslovakian affair, supported him. Parroting Keyes,

he concluded that there seemed little to recommend giving up the position

the United States held without a firm guarantee for Austria’s security.

14

Keyes’s ideas gained additional support when the State Department asked

the Joint Chiefs of Staff to review the situation. The JCS, in a report released

only a month after the Czech coup, did little more than rubberstamp Keyes’s

position.

15

on-the-job training 103

Troopers of the 4th Constabulary Regiment near Linz, November 23, 1948. Courtesy

National Archives.

From the Kremlin’s Window

What is remarkable is that Keyes’s views held such authority when he had

no special knowledge of what was happening on the other side of what

Churchill had dubbed the Iron Curtain in his Fulton, Missouri, speech. Be-

hind this dividing line between East and West was not a unified block, but a

seething political landscape held in check largely by the presence of a hand-

ful of strong-arm regimes, Soviet forces, and Stalin’s direction—a volatile

mix that would be difficult to predict under the best of circumstances. One

man who knew this well was a figure as close to Stalin as anyone: Georgi

Maximilanovch Malenkov. Born in 1902, he was too young to take part in

the Revolution, but he served in the Red Army during the civil war—as a

political commissar, not a line officer. He joined Stalin’s entourage in the

1920s. Malenkov was tough, intelligent, and ambitious. He played a promi-

nent role during World War II, though not in uniform. Malenkov slipped

into obscurity immediately after the war, but in 1948—following the suspi-

cious death of his chief rival, Andrei Zhdanov—he became Stalin’s heir ap-

parent. At forty-six, he was twelve years Molotov’s junior and relatively

young among the senior leadership.

American intelligence agencies viewed Malenkov as largely a man of

mystery. He never traveled to Europe or America, and he had few official

contacts with Western leaders. He was known to have two habits: sleeping

and working. The CIA studied his speeches and writings with a passion,

searching for any insights into the Soviet decision-making process.

Malenkov, by many accounts, advocated ameliorating the Cold War con-

frontation by withdrawing some troops from Eastern Europe and diverting

more economic energy from defense to domestic production. It was even

suspected that he was interested in improving quadripartite relations in Aus-

tria. Western intelligence largely dismissed his calls for peaceful coexistence

as merely repeating “standard formulas.” But they could only guess.

There was little opportunity to test the veracity of Malenkov’s views.

Although he was the second most powerful man in the Soviet Union, Stalin

kept a close watch over issues regarding the country’s socialist neighbors

and the occupied zones, and ministers who poked their noses in these affairs

without Stalin’s blessing risked his wrath. It was the premier who ultimately

guided Kurasov’s hand. But the intent behind that policy, Stalin’s personal

views of the role the country was to play in his scheme for a Soviet European

security zone, is still not fully understood. The Soviet leader was far less

transparent to Keyes, who saw events only through the imperfect lens of U.S.

intelligence and his contentious association with Kurasov on the Allied

Council.

on-the-job training 105

Stalin and other Soviet leaders did share one core belief: a conviction

that the inherent contradictions of Western capitalism would lead to its own

downfall. The alliance between the United States and the Europeans, with

Great Britain in particular, would not last. Petty squabbling over their self-

interests would doom any common effort. Yet the cohesion in the West, al-

though shaken by postwar hardships and East-West confrontation, ap-

peared persistent. Meanwhile, Stalin was having problems consolidating the

support of the socialist states within in his own ranks, which was dramati-

cally revealed by the situation in Czechoslovakia, and, as Malenkov’s return

to power demonstrated, within the leadership of the Kremlin as well. Such

concerns did not bode well for a quick resolution of the Austrian question.

On the other hand, there was little evidence that these troubles suggested a

determined wave of Soviet expansionism, although Keyes passionately be-

lieved this to be so.

Friendly Fire

Despite his apparent policy successes, Keyes continued to be frustrated. Dis-

appointed by the Americans’ lack of knowledge and interest in Austrian af-

fairs, he wrote to the army staff, pleading for government officials to make

more favorable references to the country in their public speeches. In re-

sponse, Wedemeyer wrote the State Department and asked for help in bring-

ing attention to the Austrian government’s “gallant fight against Com-

munism.”

16

Keyes in turn complained to Erhardt: “Congressional

committees stay here two or three days, and from the ‘Stars and Stripes,’ any-

how, sometimes give the impression that they are permanently domiciled in

Berlin.”

17

When Keyes demanded that the State Department stress Austria’s

importance to Congress, Erhardt responded that State was fully aware of the

country’s importance. Keyes doubted it.

The general also grumbled that his command was being treated as the

poor stepchild of the German occupation. General Lucius D. Clay, the high

commissioner for Germany, denied any serious disagreements with Keyes,

although documentation reveals they had differences on trade issues, com-

mand relationships, and even the need for occupation forces in Austria.

18

In

truth, Clay gave the country scant attention. He was far more concerned by

his rapidly deteriorating relations with Soviet occupation authorities in

Berlin. In 1947, the United States, Great Britain, and later France agreed to

merge their occupation areas in Germany into a single western zone—a

move Stalin bitterly opposed. As tensions escalated, Clay committed his

main effort to ensuring the viability of an independent West German state.

19

Keyes could not abide that his concerns merited so little attention. Clay

106 waltzing into the cold war

failed to appreciate the uniqueness of the Austrian situation and had fixated

on the German question to the detriment of USFA’s operations. Keyes

pushed to elevate his command’s status. He tried to persuade army leaders

in Washington to lobby the Joint Chiefs of Staff for permission to sever all

the ties that subordinated him to Clay. “A clean break is the sole solution,”

he wrote Wedemeyer, “No one in Germany is responsible for the success or

failure of my mission here so why should they be given any authority over

the means at my disposal to carry out that mission?” Wedemeyer responded

that no one questioned Austria’s strategic importance, but that the principle

of unity of effort dictated that U.S. operations in Europe not be fragmented

into separate commands. Keyes wrote back that he would play the good sol-

dier and not “buck” the decision, but the USFA commander clearly chafed

under his lack of independence.

20

He refused to let this be the last word and

raised the issue at every opportunity. The Pentagon eventually yielded.

In addition to his running battle with the military government in Ger-

many, Keyes had continuing clashes over the administration of European

Recovery Program. In addition to arguing that the Marshall Plan did not

provide economic aid for his neutralization scheme, he also disapproved of

its management. The general wanted the Economic Cooperation Authority

(ECA) mission in Paris that administered aid to work through his office.

Keyes’s proposal was ignored, and not long after the ECA began operations,

trouble started. The army became obstructionist, Erhardt reported, creating

a “tempest in a teapot” with the ECA management team. On October 20,

1948, he added conclusively, “the honeymoon is over.”

21

Flabbergasted, Er-

hardt proposed that if Keyes would not cooperate with the ECA, the State

Department should take over the high commissioner’s post. The Marshall

Plan, he believed, should not be under the army anyway. The program

needed to be set up so that authority could be progressively turned over to

the Austrian government. “As I have explained to Keyes,” he declared, “our

policy is, if I understand it rightly, to let the Austrian Government have more

and more authority and to progressively diminish the authority of the Army.

Under that formula, whether the Army likes it or not, the authority of the

Legation would also progressively increase.”

22

Erhardt was pleased to see Keyes shut out of decision making on the im-

plementation of the Marshall Plan. Not only was the general’s request that

the ECA be made subordinate to the high commissioner rejected, support

for his economic plan also floundered in Washington. The JCS referred the

plan to the State-Army-Navy–Air Force Coordinating Committee as a pri-

ority project. A subcommittee convened a working group from the newly

created Department of the Army and the State Department to study the pro-

posal. The State Department, however, worried that any additional invest-

on-the-job training 107