Carafano James Jay. Waltzing into the Cold War: The Struggle for Occupied Austria

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

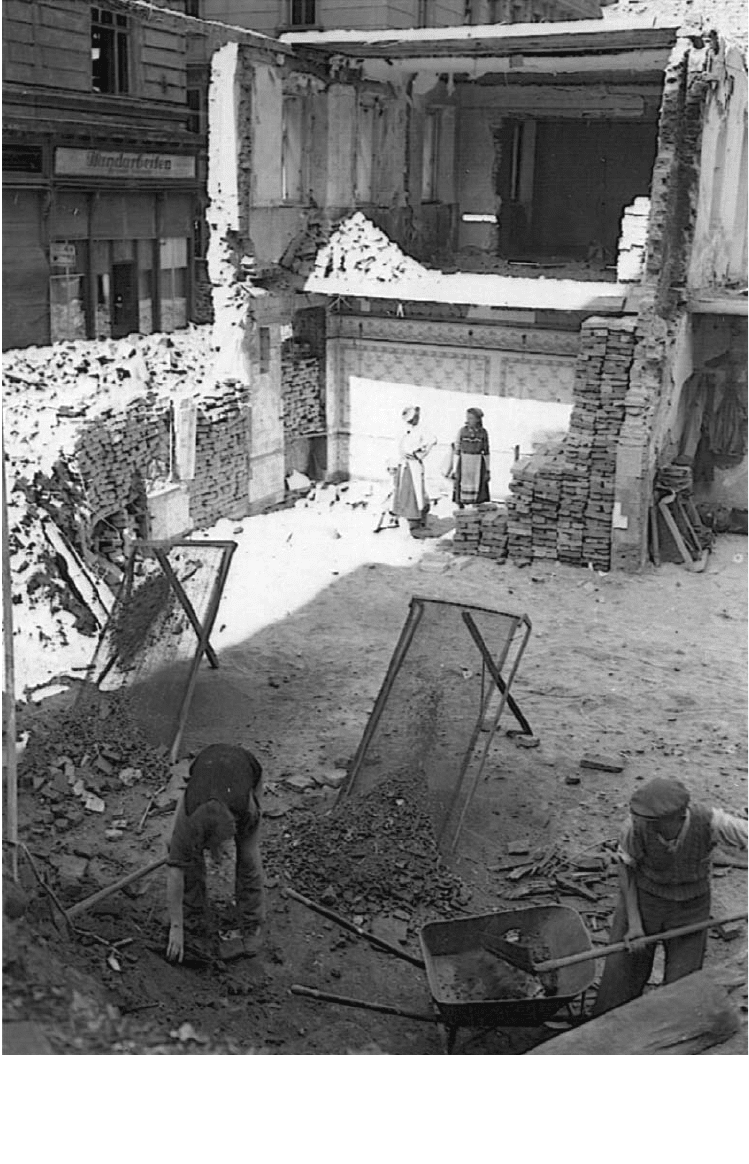

Rebuilding Vienna, September 13, 1945. Courtesy National Archives.

Clearing rubble to make way for a new building, September 13, 1945.

Courtesy National Archives.

An Austrian man with a ration of bread, Vienna, September, 1945.

Courtesy National Archives.

total breech with their wartime ally, even though the affair soured Truman’s

hopes for striking a fair deal with Stalin over the contested zone of Europe.

While the stake in Austria was not great, unlike Poland, the country had

the advantage of having the Americans at hand to serve as a counterbalance

for Soviet influence. With the United States engaged and a legitimate central

government established, the nation was in perhaps the best possible position

for an occupied country. Despite the problems and inefficiencies caused by

the initial turmoil of conflicting policies; the lack of coordination between

tactical and civil affairs units; and balancing governing with local party pol-

itics and denazification, when the new Austrian regime took office the most

critical tasks of the mission appeared largely complete. All this seemed to

bode well for the future. Even so, there was more to shepherding midnight’s

children.

Swords into Plowshares

Establishing civil government went on concurrently with the other critical

measures for implementing the disease and unrest formula. One of the most

pressing was demobilizing enemy soldiers, a task nothing less than monu-

mental. During the European campaign, U.S. forces had custody of more

than 7 million enemy troops. United States Forces Austria was responsible

for 260,000, originating from thirty-four nations, and another 179,221 en-

emy troops transferred to the command from others parts of Europe.

9

While USFET handled overall logistical support, USFA developed its

own demobilization plans, coordinating them directly with the Pentagon

and the other occupying powers.

10

The plans established three require-

ments. Primary disarmament included processing personnel and destroying

their weapons, ammunition, and equipment. At the same time, USFA began

secondary disarmament, removing stocks from supply dumps, depots, and

warehouses. Final disarmament, which called for demilitarizing of factories

and demolishing fortifications and other military infrastructure, would

follow.

The army never published formal doctrine or trained on disarming pro-

cedures, but of all its postwar tasks it was best prepared for this job. Mili-

tary leaders recognized these activities as a legitimate extension of combat

and tackled them enthusiastically, drawing on lessons learned from World

War I and the Mediterranean and European campaigns to perfect their

methods. Troops immediately began the first step, rounding up enemy forces

and separating them from their weapons. Most surrendered in large forma-

tions. German commands were ordered to retain unit integrity, transport-

ing and sustaining themselves in designated areas. At least that was the idea.

shepherding midnight’s children 61

The Americans quickly discovered that the defeated troops did not have ad-

equate resources to care for themselves. In addition to supply and transport

assistance, substantial administrative support was needed to register and

process enemy personnel and equipment.

The initial priority was confiscating weapons, essential in the event of

riots or other disturbances. It was also important to eliminate weapons as

rapidly as possible to prevent theft, black market sale, or pilfering war tro-

phies by sticky-fingered GIs. Arms, equipment, and ammunition were de-

militarized by the most expedient means at hand: burning, crushing, bury-

ing, or blowing up. United States Forces Austria destroyed its fair share of

the more than 1 million tons of German equipment seized by U.S. forces.

In the meantime, enemy soldiers were prepared for release. This func-

tion was the responsibility of locally appointed military zone commanders.

A typical center run by a combat regiment could handle up to eighty-five

hundred soldiers a day. Marched to the reception camp in lots of one thou-

sand, the Germans were sent through a series of substations for registration,

classification, security checks, fingerprinting, delousing, physical exams,

briefings, and receiving discharge certificates and clothes to replace Wehr-

macht uniforms. Finally, each group was transported to the men’s coun-

try of origin.

One of the most innocuous of these tasks offered unexpected problems.

Disarmed enemy forces, civilian laborers, displaced persons, and repatriated

Allied personnel had all been issued surplus American uniforms. A rash of

crimes reportedly committed by U.S. forces led officials to suspect the cul-

prits were really civilians or former enemy soldiers in American military

garb. In September, USFET ordered all issued clothing dyed distinctive col-

ors. By December, the command reported the task had been largely accom-

plished. This was far from true. One problem was a theaterwide shortage of

dyes. There was also a howl of protest from displaced persons ordered to

don blue uniforms. “They were being forced to wear an identifying badge

of a ‘lower order,’ just as Nazis had required all Jews to wear the Star of

David,” a UNRRA camp commander recalled, an act that was “bitterly re-

sented.” As a result, the UNRAA simply ignored the army, and the rule,

which “was never repealed,” was never enforced.

11

Fretting over uniforms reflected the many challenges of trying to mini-

mize security threats while processing thousands of men every day. Counter

Intelligence Corps (CIC) agents scrutinized internees and impounded and

examined diaries, papers, and identification documents. The screening seg-

regated suspected war criminals and gathered information on underground

operations and illegal activities. Meanwhile, combat troops established

checkpoints and ran periodic sweeps searching for arms caches, contra-

62 waltzing into the cold war

band, and stragglers. Sometimes troops even found themselves deep in the

Austrian woods chasing high-ranking German officers and shooting it out

with fanatical SS men, though these incidents were the exception rather than

the rule. By the end of the year, the command discharged over 391,000 pris-

oners and transferred another 99,343. In July, 1946, USFA reported custody

of only 242 enemy soldiers. By March, 1947, secondary and final demobi-

lization were also largely complete.

Disarmament directives also banned all signs of paramilitary activities,

including veterans’ associations, uniforms, flags, military gestures, salutes,

insignia banners, military parades, anthems, and martial music. The com-

mand noted that the Austrians had “a disturbing tendency” to form organi-

zations.

12

The Allies took these prohibitions seriously, eliminating every-

thing from youth groups to ski clubs. This was believed to be particularly

important as the history of Austria’s First Republic was littered with ex-

amples where parties had used private armies to wage political warfare.

Thus, over the next two years, the occupiers identified and broke up 220 dif-

ferent organizations.

Plans also called for cleansing law enforcement agencies. This practice

complicated reestablishing public safety since disarming the police and

purging their ranks of Nazis made them essentially ineffective. Austrian

leaders complained bitterly because such measures compromised rather

than enhanced prospects for establishing a stable state.

13

Some Americans

agreed that this step was intrusive and wrongheaded. One military govern-

ment officer wrote: “I was always disturbed and sometimes shocked when I

witnessed a total disregard of the very rights for which I thought this war

was fought. As I used to say frequently in Austria, we can never have a world

at peace as long as we ourselves resort to practices which give the appear-

ance of Out-Nazi [sic] the Nazis.”

14

To military commanders, however, these

concerns were less important than establishing a safe and secure environ-

ment for their forces and destroying all Nazi influences.

Heightening the concerns over physical security were persistent reports

of “Werwolfe,” covert teams of Nazi agents trained to conduct espionage

and guerrilla warfare. The Werwolf threat played a significant role in shap-

ing perceptions during the initial occupation. According to one report, 150

candidates were recruited shortly before the end of the war. Of these,

seventy–eighty—composed of a mix of Wehrmacht soldiers, SS troopers,

civilian Nazi Party members, and Hitler Jugend—completed training and

were dispatched into the countryside. There were also rumors of twenty-

four Werwolfe near Schleedorf.

15

Intelligence on suspected Werwolf operations persisted through July,

1945. There were also numerous reports of minor acts of sabotage, unex-

shepherding midnight’s children 63

plained fires, explosions, ambushes, and cut communication wires. Al-

though an underground movement never materialized, U.S. fears were not

wholly unwarranted. Werwolf organizations did exist, but their operations

were ineptly administered, enjoyed little popular support, and withered in

the face of massive Allied military force. In the end, the demobilization of

Austria was a complete victory for the disease and unrest formula.

Friends and Enemies

While pacifying Austria was an immediate success in terms of reestablishing

a pliant political order, U.S. measures had unintended—and not always

constructive—consequences on rebuilding civil society. Civil society repre-

sented the community’s public associations, acquired and nurtured through

means other than the mechanisms of government. These were the areas of

private sociability and discourse, such as unofficial groups, meeting places,

and informal relationships. In terms of rehabilitating society, they would

play an equally important role in fostering democracy, toleration, trust, and

respect for the rule of law. United States Forces Austria’s initial efforts pri-

marily focused on the country’s formal institutions. Concern with civil so-

ciety was primarily limited to supporting the disease and unrest formula

through the denazification program.

Dictating how soldiers would treat the Austrian people was an impor-

tant and sensitive aspect of the effort to rebuild civil society, but comman-

ders gave it little forethought. Neither a liberated country like France nor a

defeated nation like Germany, the issue was whether to recognize Austrians

as equals and permit a free interchange between civilians and occupation

troops or to remain distant. Complicating the decision was the fact that

many Austrians had actively supported the Nazi regime.

16

Supreme Head-

quarters Allied Expeditionary Force opted for strict limits, declaring, “In the

initial stages of the occupation all social contacts between the Army and the

civil population will be prohibited until such time as the situation warrants

the lifting of the prohibition.”

17

This directive barred all informal contact,

as well as setting a curfew prohibiting civilian movement after dark. These

restrictions mirrored the policy for Germany.

Nonfraternization rules were intended to minimize contact between

soldiers and the populace. Here the generals had a number of concerns.

Physical security was foremost. They were worried about terrorism, sabo-

tage, and inadvertently compromising military secrets. There were unstated

issues as well. One was crime. Civilians or German soldiers wearing Amer-

ican uniforms aside, criminal offenses by U.S. soldiers were not infrequent.

In particular, the gains from exchanging goods and services on the black

64 waltzing into the cold war

market were extraordinary and a great temptation. Limiting contact with

civilians was one technique for discouraging profiteering.

18

Discipline and health issues were also concerns. Restrictions, it was

hoped, would, “avoid the lax morals and numerous temptations present in

a country whose social codes had been overturned by Nazism and the influx

of refugees from many lands.”

19

Prospects for contagious diseases, especially

venereal infection and typhus ran high. Not surprisingly, the rate for social

disease among soldiers skyrocketed.

20

In addition to health concerns, mini-

mizing contact would preclude confrontations that might explode into civil

disturbances. Finally, there were constant worries that any sensational pub-

licity over fraternization might portray the occupation in an unfavorable

light. Troops that seemed too generous or familiar might prompt further re-

sentment from a people who preferred to have their men returned home as

soon as possible.

While the generals wanted to be cautious and prudent, many GIs were

desperate to meet women. Often-told stories of how high-ranking USFA of-

ficers socialized with Austrians and unsubstantiated rumors that German

shepherding midnight’s children 65

U.S. military police and Austrian officials coordinating a raid on the black market,

October 6, 1946. Courtesy National Archives.

prisoners of war were roaming freely in the United States heightened resent-

ment. Enforcing the ban on fraternization became a serious discipline chal-

lenge. “If ever there was an order that had to be explained,” one general

lamented, “the non-fraternization order is it.”

21

The predicament faced by commanders was not new. The United States

had adopted a nonfraternization rule after World War I for the same rea-

sons. That policy was an abject failure.

22

In fact, commanders found that to-

tal nonfraternization hindered rather than improved conditions. Fraterniza-

tion policies after World War II proved no more successful. Commanders

used lectures, pamphlets, films, newspapers, and magazine articles to justify

policies. Some units employed special patrols or conducted bed checks. Oth-

ers relied on the military police. These efforts had little effect. There were no

standardized rules, penalties, or enforcement procedures.

In general, nonfraternization proved to be highly unpopular and, ac-

cording to an official army report, was never seriously imposed in Austria.

23

Americans were not the only ones who disapproved. The French ignored all

attempts to restrict fraternization. Soviet commanders had a policy, but is-

sued no specific regulations to implement it. The British pursued a course

66 waltzing into the cold war

Military and Austrian police arresting black marketers in the Karlsplatz, Vienna,

October 2, 1945. Courtesy National Archives.

similar to the Americans but found their soldiers equally reluctant to accept

prohibitions.

24

The Austrians also deeply resented such rules. Treating the

country in the same manner as Germany seemed contrary to the promise of

a free and independent state.

In the absence of an overt threat and faced with widespread dissatisfac-

tion, commanders felt pressured to reconsider. Pentagon officials autho-

rized backtracking on nonfraternization rules, but Generals Clark and

Eisenhower were wary, wanting to judge the reaction both in the United

States and Europe before loosening prohibitions. In July, while discontent

mounted, Clark left for a whirlwind trip to Rio de Janeiro to welcome home

the Brazilian expeditionary force that had fought under his command in

Italy. In his absence, General McCreery decided to relax the rules for British

troops. General Gruenther called an emergency meeting of USFA’s staff and

penned a statement for the press concluding that the improving security con-

ditions meant restrictions could be relaxed soon. He intended to release the

statement on Clark’s return. Then Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery

announced the immediate lifting of all restrictions in the British zone of Ger-

many. Eisenhower felt compelled to issue a parallel decree. When the draft

was forwarded to USFA, Gruenther protested when he discovered that it ap-

plied to both Germany and Austria. Fraternization, he contended, was a po-

litical issue for which Clark was responsible directly to Washington. The

flurry of finger-pointing prompted Erhardt to remark that he was reminded

of a tag line from Jimmy Durante’s radio skits: “Everybody is trying to get

into da act.” On July 14, Eisenhower lifted the theaterwide ban on conver-

sations with civilians in public. To avoid embarrassment and confusion,

Gruenther hastily released a statement proclaiming that Clark had “stated

today that the modification of the non-fraternization order issued by Gen-

eral Eisenhower would apply to United States Forces in Austria.”

25

It was a

neat trick given that the USFA commander was still in South America.

The declaration met with little public enthusiasm—in part due to con-

fusion surrounding the announcement and in part because many thought

it did not go far enough. One State Department official called the policy a

“tragi-comedy.”

26

Soldiers were being ordered to ignore the Austrians, even

those who had opposed the Nazis and been sent to concentration camps. “It

looks like,” his report continued, “A deliberate effort—and an effective

one—to perpetuate and to stimulate hatred. You can’t square it very well

with the Moscow Declaration and the high plane of most of our declara-

tions. Our boys are supposed to, and to a considerable extent do, walk

through the streets not seeing anyone but each other; if they have to do busi-

ness with Austrians they should not smile, there should be no courtesies and

of course they shouldn’t shake hands.”

27

Regardless of any contributions

shepherding midnight’s children 67