Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

244 Craig Norris

genre in weekly comic magazines for boys and young adults were the boxing

story Ashita no Joe (1968) and the baseball story Kyojin no Hoshi (1966).

The 1960s also saw the steady maturing of the manga market and titles which

reflected this expansion beyond the children’s audience. Young adults, who

had read manga as children, began demanding more sophisticated and adult

material. This included not only stories set in the adult workplace and the

world of leisure but also avant-garde manga such as the alternative manga

magazine Garo (1964–2002). Garo serialised the popular peasant revolt

story The Legend of Kamui (Kamuiden) and became an important platform

for alternative ‘art’ manga in Japan.

The 1970s were marked by a group of female manga artists who pio-

neered a new approach to sh

¯

ojo manga. Sh

¯

ojo can be narrowly defined as

manga aimed at girls less than 18 years of age, but is often more broadly

applied to manga aimed at a female readership. While sh

¯

ojo includes a range

of genres such as sport, horror, science-fiction and historical drama, it is

commonly associated with slender elegant male characters and romantic,

fantasy-based plots. Matt Thorn estimates that today ‘more than half of

all Japanese women under the age of 40 and more than three-quarters of

teenaged girls read manga with some regularity’.

32

The sh

¯

ojo artists are

mainly female and the market is a lucrative one, with Ribon, a popular

manga magazine for girls, reaching a peak of one million sales per month

during the late 1990s.

33

Successful sh

¯

ojo artists such as Naoko Takeuchi (cre-

ator of Sailor Moon) have also become millionaires through the popularity

of their manga. While initially dominated by male authors,

34

by the 1970s

a group of female artists known as Nij

¯

uyonen Gumi (Year Twenty-Four

Group) pioneered a new approach to sh

¯

ojo manga introducing new themes

and approaches such as homosexual love.

35

These artists, all born in the 24th

year of Showa (1949), depicted themes such as romantic love between beau-

tiful young boys, for example, Keiko Takemiya’s Kaze to Ki no Uta (The

Sound of the Wind and Trees, 1976) and Moto Hagio’s T

¯

oma no shinz

¯

o (The

Heart of Thomas, 1974); while Yumiko

¯

Oshima’s short manga Tanj

¯

o (Birth,

1970) depicted teen pregnancy and abortion. These titles helped broadened

the audience and content of sh

¯

ojo manga.

As shown previously in Table 13.1, developments in manga’s layout

and composition, graphic style, and gender-specific formats had become

firmly established by the 1970s. The following six illustrations represent

key aspects of these developments.

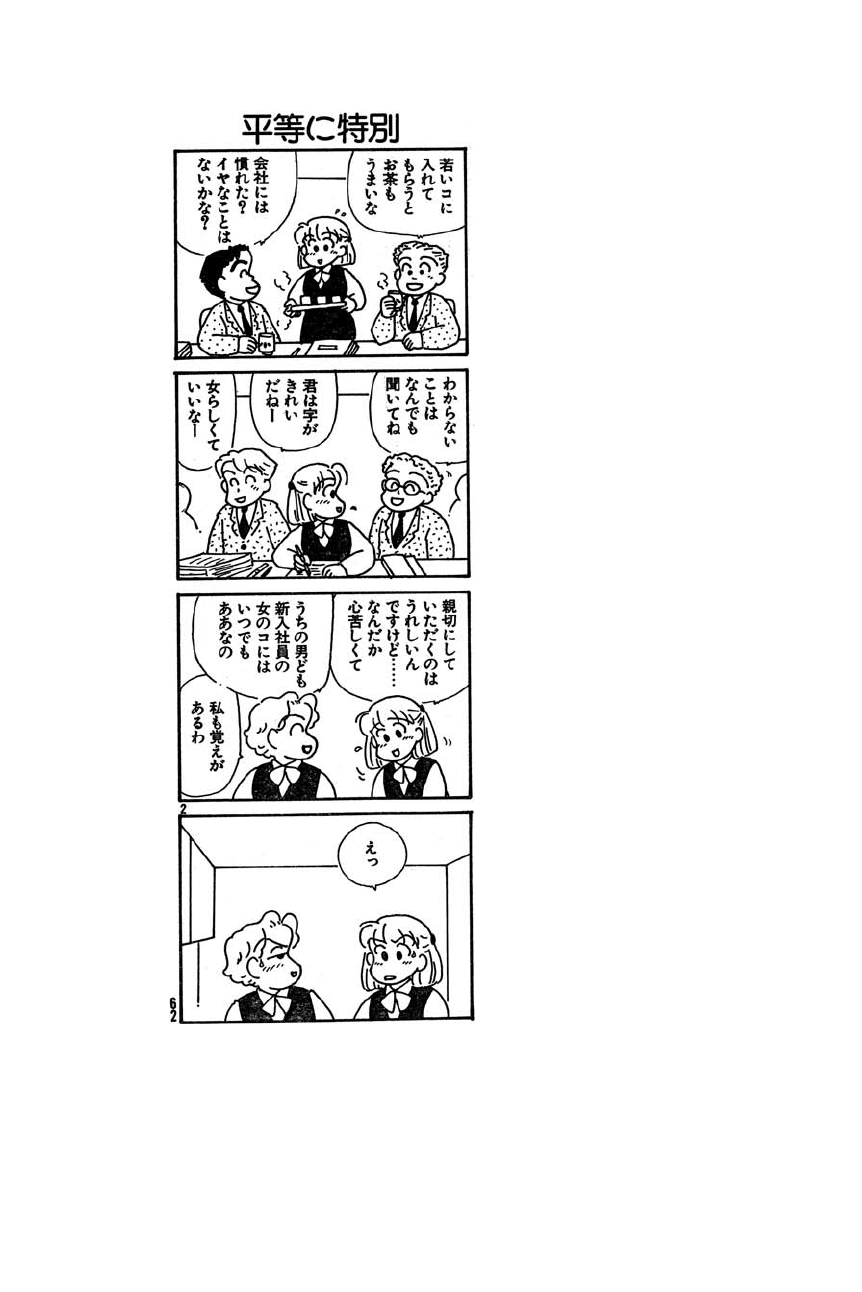

Risu Akitsuki’s OL Shinkaron (Office Lady Theory of Evolution)

(Figure 13.1), published in Kodansha’s comic magazine Morning from 1989,

Manga, anime and visual art culture 245

Figure 13.1 OL Shinkaron’s simple four-panel layout and gag structure is typical

of the yonkoma manga form.

Source: Risu Akitsuki ‘OL Shinkaron’ (‘Office Lady Theory of Evolution’)

Sh

¯

ukan M

¯

oningu,(18 April 1996)p.62

c

dddd/ddd

c

Risu

Akizuki/Kodansha Ltd.

246 Craig Norris

demonstrates the yonkoma convention of a short, self-contained gag deliv-

ered in four panels. Most content is drawn from everyday observations, as in

this example, where a new female employee misunderstands the special con-

sideration she receives from her male colleagues, as emphasised by the title

of this manga By

¯

od

¯

o ni Tokubetsu (Equally Special). The humour draws

upon the stereotype of the male-dominated workplace where the female

employee has received kindness from the male workers (the first two pan-

els), however her senior female colleague dismisses this kindness as being

only a temporary male prerogative for patronising new female employees.

This simple four-panel layout worked perfectly for the newspapers and

magazines that often carried yonkoma manga, as they had limited space and

fixed measurement requirements. However, the story manga form reacted

against these limitations, offering epic narratives with an equally epic diver-

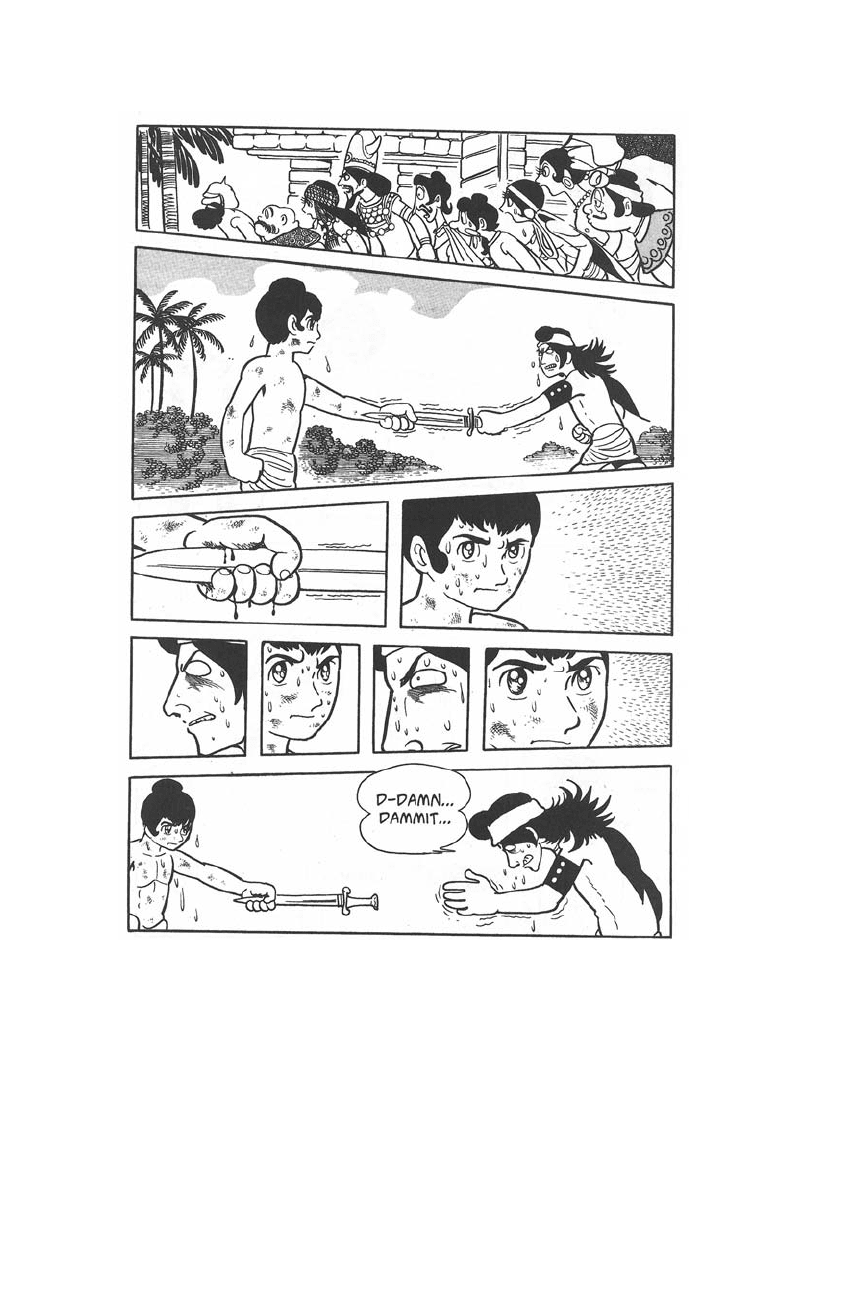

sity of panel sizes and dynamic graphics. Tezuka’s Buddha (Figure 13.2)is

representative of this approach. In this example we see the main character,

Siddhartha, disarming Bandaka – a scene that is comprised of many frames,

in contrast with yonkoma’s format where one scene equals one frame. The

tension and drama is carefully developed and prolonged through the use

of close-ups and variations in panel size. Tezuka’s Buddha also offered a

novelistic approach to manga, telling the story of the historical founder of

Buddhism spread over fourteen volumes.

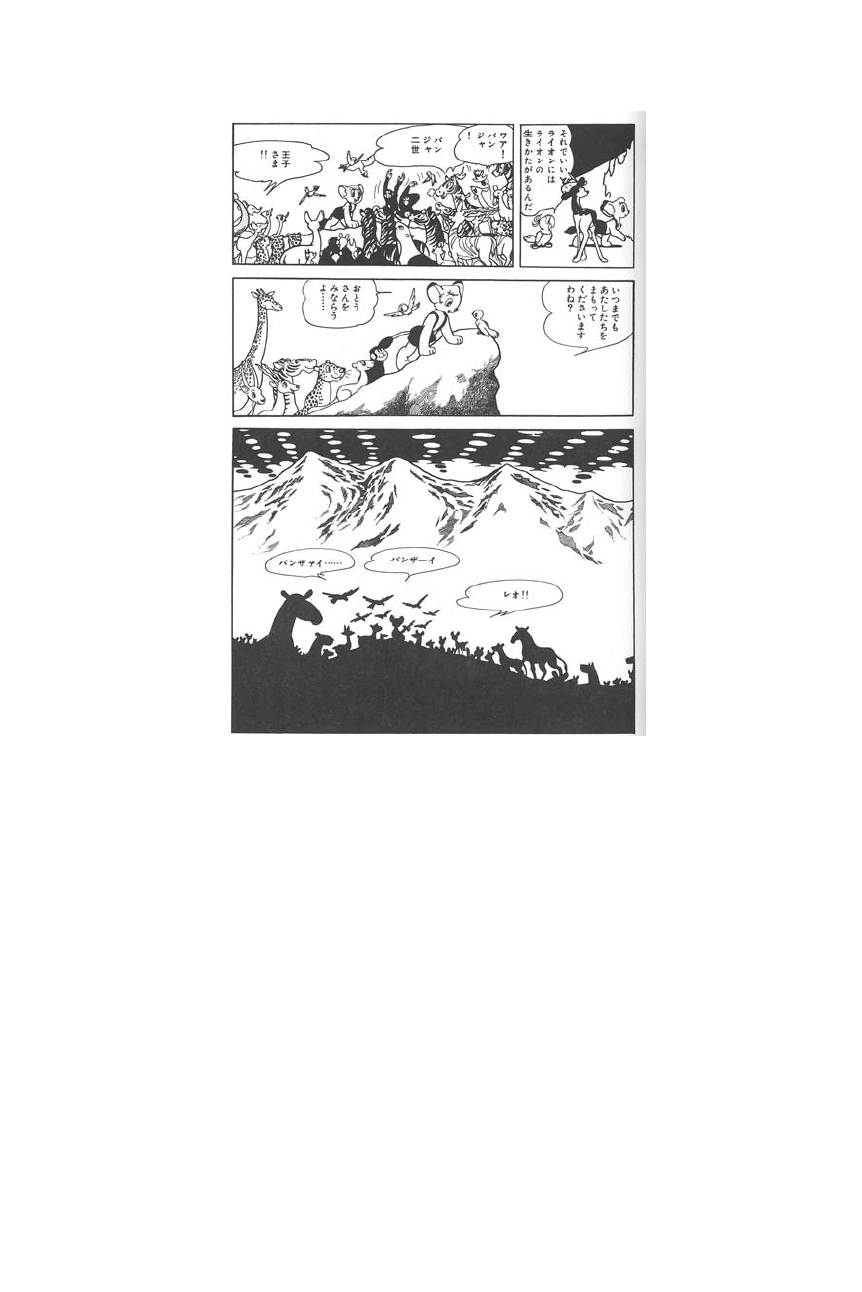

Tezuka was also significant in popularising the cute graphic style often

associated with kodomomuke manga. Jungeru Taitei (Jungle Emperor –or

as it became known in the West, Kimba the White Lion) portrayed cute,

humanised animals while also offering humanitarian principals to its audi-

ence. This style is evident in Figure 13.3, where the recently orphaned

Leo assumes his role of Jungle Emperor after contemplating the fate of his

father. While Tazuka is also notable for responding to changing political

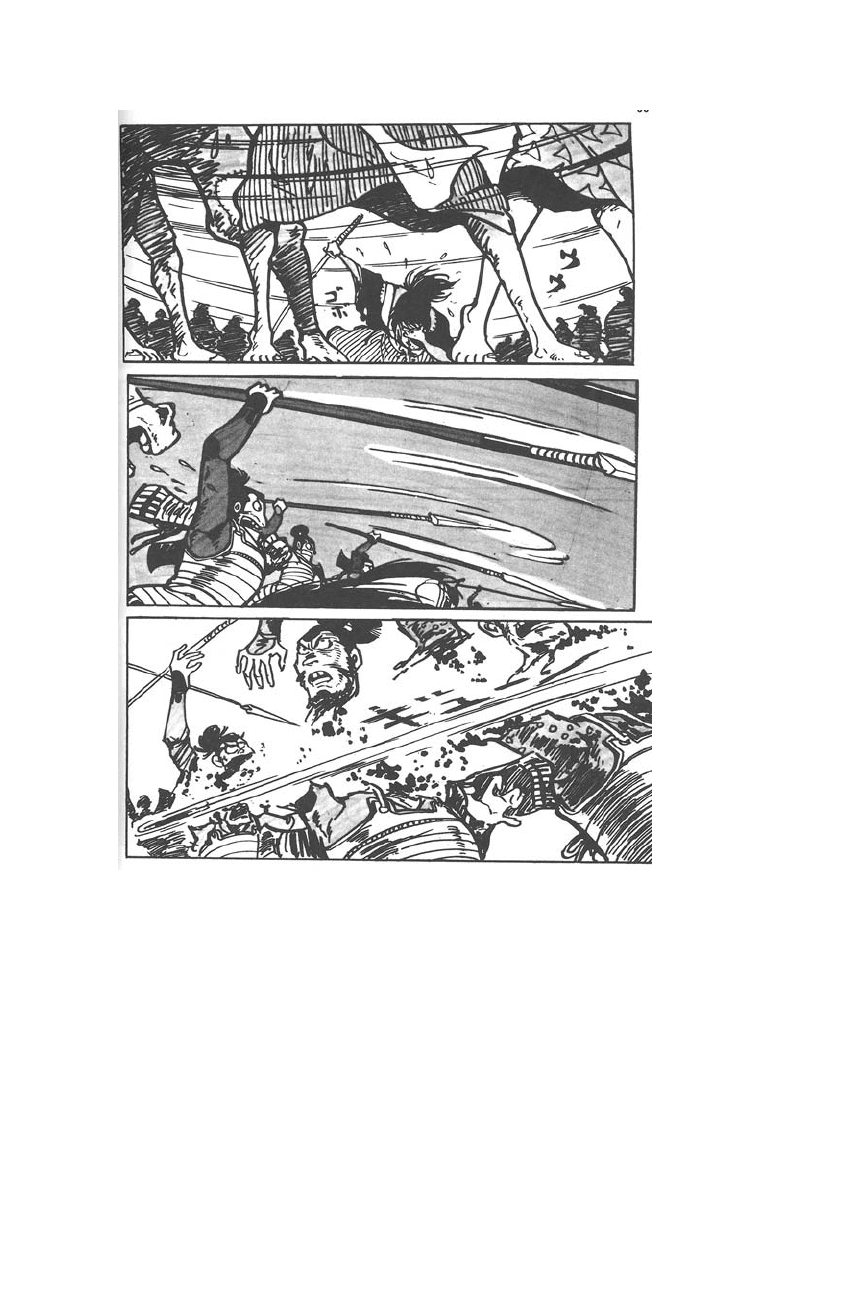

and cultural sentiments of the 1960sand70s through his gekiga manga

such as Bomba! and Song of Apollo, one of the best examples of this form

is Shirato’s Ninja Bugeich

¯

o (Figure 13.4). As this example shows, gekiga’s

graphic violence offered a grittier ‘realism’ than the cuter style of kodomo-

muke manga. Ninja Bugeich

¯

o’s portrayal of the harsh conditions faced by

peasants in feudal Japan also offered a more dramatic theme for an older

audience that resonated with post-Occupation issues such as criticisms of

the Japan-America Security Treaty.

While gekiga reflected political and cultural concerns of the time, as

already noted, it was in sh

¯

onen and sh

¯

ojo manga that the biggest market

for manga was to be found. These two examples (Figures 13.5 and 13.6)

Manga, anime and visual art culture 247

Figure 13.2 Siddhartha’s disarming of Bandaka in Tezuka’s Buddha shows the greater

layout complexity of the story manga form.

Source: Osamu Tezuka Buddha (US reprint) Vertical: 1st American edition (11 July 2006)

Buddha vol. 2,p.339

c

Tezuka Productions.

248 Craig Norris

Figure 13.3 Cuteness and melodrama combine in Tezuka’s Jungeru Taitei.

Source: Osamu Tezuka Jungeru Taitei.

c

Tezuka Productions.

exemplify the different approaches associated with sh

¯

onen and sh

¯

ojo

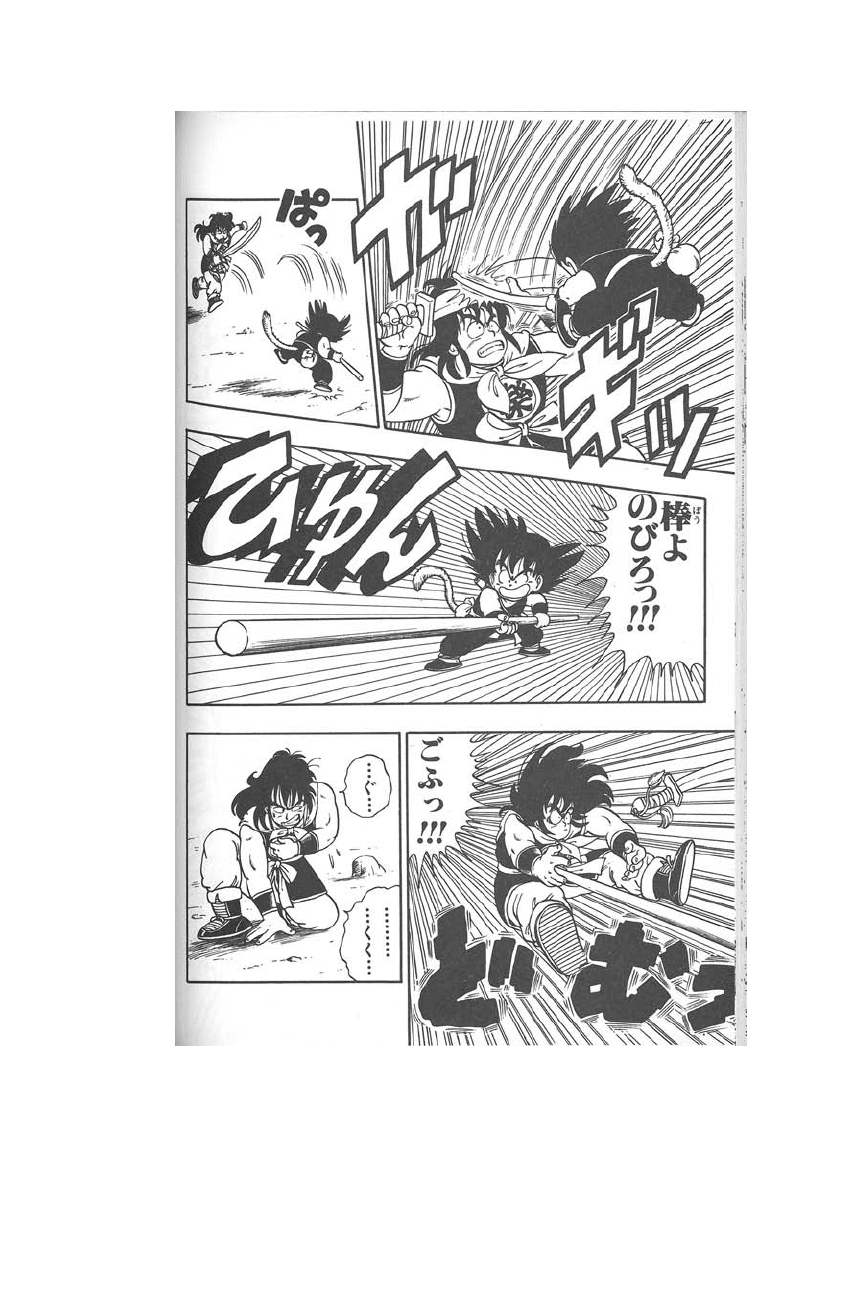

manga. Son Goku’s battle in Dragon Ball (Akira Toriyama, BIRD STU-

DIO/Shueisha) (Figure 13.5) conveys sh

¯

onen manga’s greater emphasis on

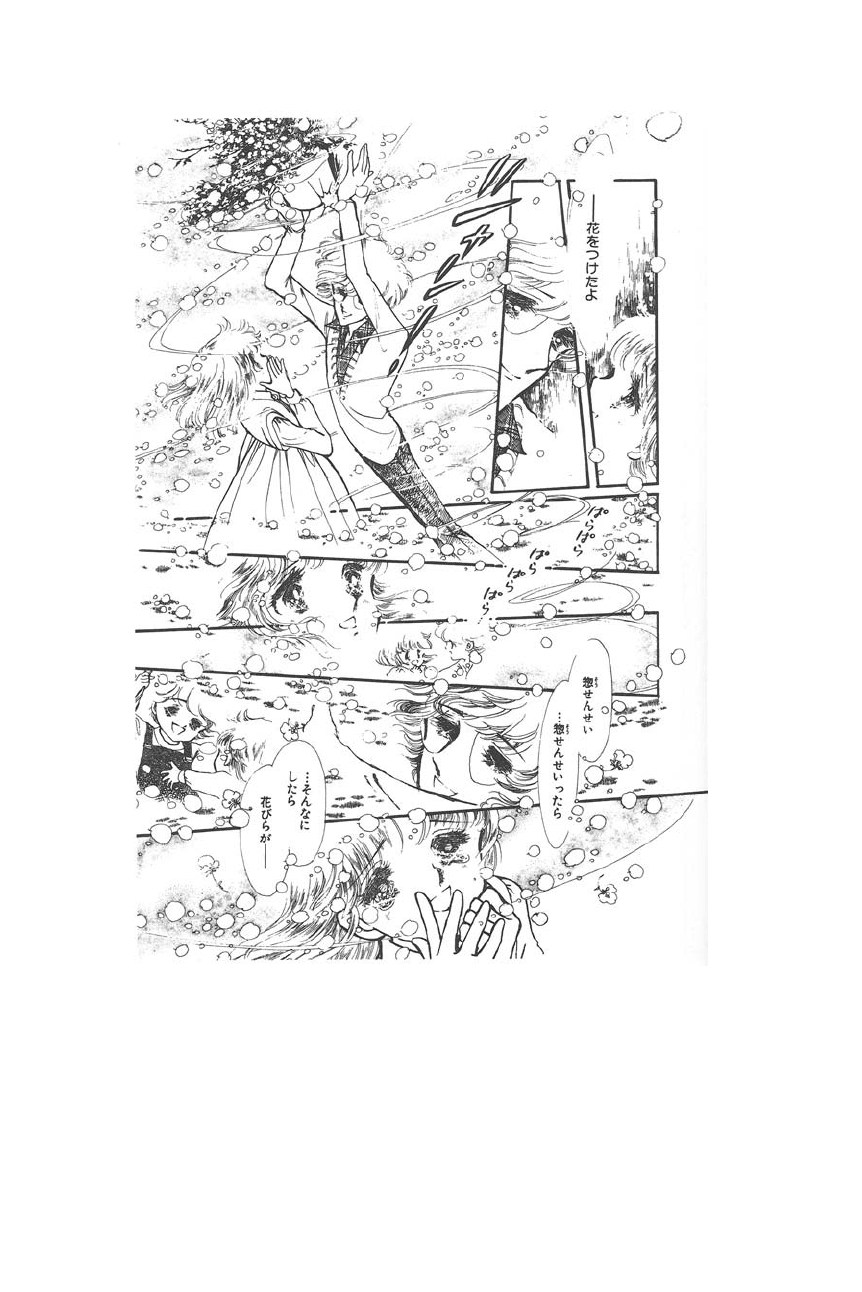

action centred on male protagonists. Figure 13.6, a page from Tachikake’s

Hana Buranko Yurete demonstrates sh

¯

ojo manga’s more creative page lay-

out, reflecting the internal emotional intensity of the main character. While

these examples illustrate manga’s key changes since the postwar period,

manga’s development did not end in the 1970s.

A further significant innovation was to occur in the 1970s with the pop-

ularisation of the tank

¯

obon (paperback) format for manga. Popular manga

previously serialised in weekly and monthly magazines were compiled in a

Manga, anime and visual art culture 249

Figure 13.4 Shirato’s Ninja Bugeich

¯

o conveys the darker adult themes of gekiga manga.

Source: Sanpei Shirato Ninja Bugeich

¯

o (Secret Martial Arts of the Ninja) 1959–62 (1997

reprint) vol. 3,p.388.

c

Sanpei Shirato/Akame Production.

higher-quality paperback more portable for commuters and more attractive

for collectors. The tank

¯

obon soon replaced manga magazines as the main

revenue stream for manga publishers.

By the 1980s sales of manga had peaked, but continued to do well into

the 1990s. Even after the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in the 1980s

250 Craig Norris

Figure 13.5 Toriyama’s Dragon Ball is an excellent example of sh

¯

onen manga’s ability to

do action and adventure perfectly.

Source: Akira Toriyama Dragon Ball (1985)vol.1,p.124

c

Akira Toriyama, BIRD

STUDIO/Shueisha.

Manga, anime and visual art culture 251

Figure 13.6 The story of a young girl coping with the divorce of her Japanese and French

parents forms the emotional nexus typical of sh

¯

ojo manga in Tachikake’s Hana Buranko

Yurete.

Source: Hideko Tachikake Hana Buranko Yurete (1978–80)

c

Hideko

Tachikake/Shueisha.

252 Craig Norris

manga sales still totalled ¥586 billion in 1995.

36

By the 1980sand90smanga

had become mainstream and were read by nearly everyone of all ages. Kyoyo

Manga (academic or educational manga) is an example of the mainstream

appeal of new forms of manga as they were used to inform and educate

readers on a range of topics from history and annual festivals to cooking

and other DIY areas.

Manga changed again in the 1990s as editors asserted a stronger role in

the creative processes of manga production. Kinsella

37

argues that because

most editors were more wealthy and educated than artists, adult manga in

particular was reformed around their more privileged tastes and interests.

This move away from the working class, artist-created, counter-culture sto-

ries of the 1960sand1970ssuchasNinja Bugeich

¯

o (Secret Martial Arts of the

Ninja, 1959–62)andGaro can be seen in the more factual and niche-interest

manga such as the political and economic series Osaka Way of Finance

(Niniwa Kin’y

¯

ud

¯

o) and the extensively researched nuclear-submarine story

Silent Service (Chinmoku no Kantai). This period also saw the expansion

of the global market for manga. Manga began to gain a stronger foothold

in the US, long a niche market for Japanese popular culture. With the

release of Akira (1988 Japan release, 1989 US release) and Ghost in the Shell

(1995 world-wide release), both based on original manga, Japanese manga

and anime began to attract greater international attention than ever before.

These titles were much more ‘adult’ that the standard animation of the time,

and their dystopian, cyberpunk themes came at a time of great interest in

the approaching millennium. In 1998, Ghost in the Shell reached number

one on Billboard’s video chart in the US.

By the early 2000s, the manga industry had broadened beyond the

familiar Japanese publishers (K

¯

odansha, Sh

¯

ueisha, Sh

¯

ogakukan) to include

a smaller number of transnational manga distributors and publishers

(Tokyopop, Viz Media and Seven Seas Entertainment) and achieved a glob-

ally dispersed audience, a trend discussed in more detail in chapter 19.

For companies such as K

¯

odansha, manga was still an important generative

source for other media platforms – TV animation, video games, merchan-

dise and so on. While there are current concerns that the Japanese manga

market is becoming stagnant and its fortunes are declining – the circula-

tion of weekly manga magazines has been in steady decline for the last

decade – many of the most successful anime, video games and merchandis-

ing lines began as manga. Naruto began in the comic magazine Akamaru

Jump (1997) and has gone on to become a world-wide hit through anime,

Manga, anime and visual art culture 253

card-game, video game and merchandise spin-offs. The enormously

successful Dragon Ball franchise likewise began as a manga series in 1984.

In addition to these manga-inspired titles, the 2000s have been dominated

by the growth of large, globally successful brands that exist across various

media platforms. Power Rangers, adapted from the live-action Japanese TV

show, was broadcast in the US in 1993, and by 2007 it had expanded to 15

television seasons, 14 series and two films. Its success was overshadowed by

the greater popularity of Pokemon, produced by the video game company

Nintendo and created by Satoshi Tajiri, which became a successful video

game, anime, and character-related business franchise.

Shogakkan’s Pokemon, the animated version of Nintendo’s portable

game software, was the first huge success by a Japanese anime overseas.

Released in 45 countries and regions around the world, as of the third

instalment of the series it had generated overseas box office revenue of

¥38 billion, double its earnings in Japan. Pokemon’s gross global earn-

ings, including related products, are estimated at ¥3 trillion.

38

Pokemon’s

global success has helped establish the enormity of Japan’s character-related

industry, and has maintained Japan’s contribution to the global children’s

entertainment sphere.

Manga has also moved into online environments, with both K

¯

odansha

and Sh

¯

ogakukan offering online manga content and various downloads

that extend the audience’s access to manga in a more interactive online

environment. Mobile phone manga is also available through companies

such as Toppan Printing, allowing readers to enjoy manga without worrying

about weight or bulk. This move away from print media to digital formats is

extended even further by hand-held video devices such as Sony’s PlayStation

Portable (PSP) and Nintendo DS which offer a number of titles based upon

popular manga (Dragon Ball, Naruto) or drawing upon the manga style

(Cooking Mama and Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney).

Manga industry

Manga’s development and distribution over varied media platforms reveals

shifting relationships between the industry and audience. In recent times,

manga’s development has been impacted by the rise of OEL (original

English-language) manga, which straddles the Japanese/Western divide.

OEL manga involves taking the ‘design engine’ of Japanese manga and

using it to tell stories created by non-Japanese artists for a non-Japanese