Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

184 Hideo Aoki

bases and tourism. In 2007, the population of Okinawa prefecture stood

at 138 000.

9

Finally, Japan has a substantial number of Koreans, known as Zainichi

Koreans, throughout the nation. Japan invaded the Korean peninsula and

annexed it in 1910. The Japanese government then instituted colonial poli-

cies through which they exploited the land and resources of Korea. Koreans

living under destitute circumstances migrated to Japan. During the Second

World War many male Koreans were carted off for forced labour in Japan.

Though many Koreans returned to their homeland when Japan lost the war

in 1945, those who had lost their livelihood in Korea remained in Japan.

‘Zainichi Koreans’ refers to those who remained and their descendants. This

group possesses special permanent residency status,

10

and their population

numbered 443 000 in 2006.

11

Some Zainichi Koreans have been naturalised

as Japanese, though the extent of this population is unknown. The Zainichi

Koreans have been discriminated against in various ways, and many keep to

their own networks of relatives and fellow Zainichi Koreans. The Zainichi

Koreans possess their own ethnic culture (Korean Confucianism, language

and custom); they have remained in Japan for over half a century and have

formed their own identity, different from the national identity of Koreans

in the motherland.

A few points of comparison will reveal the location of burakumin vis-

`

a-vis these minority groups. Most important in this regard is the fact

that the Ainu, Okinawans and Zainichi Koreans are ethnic minorities

whereas burakumin are not. In terms of the official definition of nationality,

burakumin, Ainu and Okinawans are Japanese, while Zainichi Koreans are

not in the sense that they do not hold full Japanese citizenship.

All of these minorities emerged as products of modern Japan’s exter-

nal and internal colonialism. As Japan embraced modernity, discrimination

against burakumin and Ainu intensified internally. At the same time, it

brought about the creation of the Okinawan and Zainichi Korean minority

groups externally. In other words, the dominant culture of Japan that gave

rise to discrimination against burakumin contributed to the formation of

the social structures that created ethnic minorities externally. In this sense,

discrimination against burakumin is firmly connected with the matrix of

structural ethnic discrimination and occupies a strategic domain in the con-

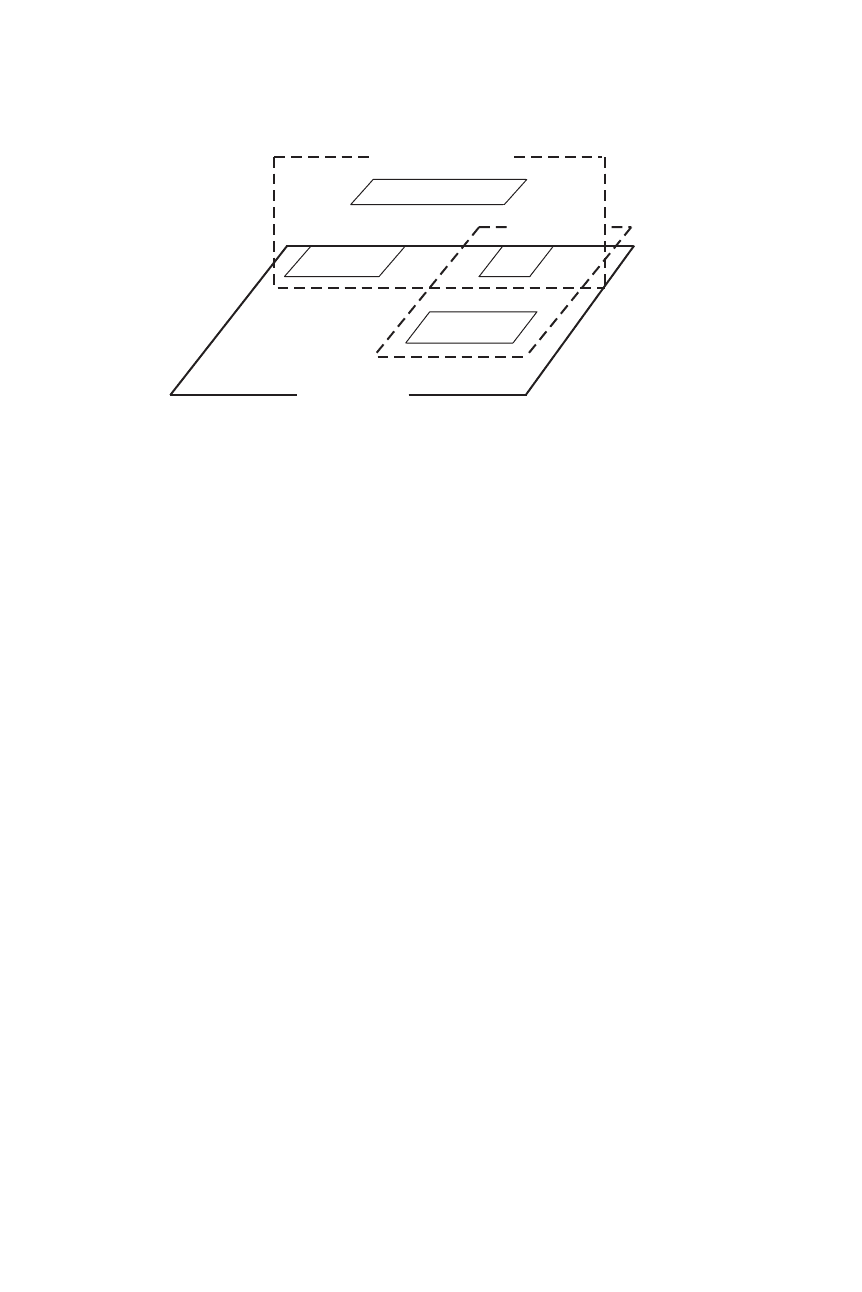

text of contemporary minority issues in Japan, as Figure 10.1 shows.

There appears to be some status hierarchy among these minority groups.

‘When I was growing up, people from the general public (non-burakumin)

used to throw stones at me,’ said a burakumin panellist at a symposium.

12

Buraku culture 185

<Japanese Society>

<Ethnic Minority>

Koreans in Japan

<Japanese>

Okinawans Ainu

Burakumin

Dominant Japanese

<JAPANESE>

Figure 10.1 Burakumin and ethnic minorities in Japan.

Upon hearing this, a Zainichi Korean panellist said, ‘When I was growing up,

burakumin used to throw stones at me.’ To which an Ainu panellist replied,

‘When I was growing up, Zainichi Koreans used to throw stones at me’.

This chain of internal discrimination within minority groups suggests the

structural complexity of minority existence. Because burakumin are subject

to discrimination by people who are no different in terms of nationality,

race and ethnicity, they do not have a refuge in which they can completely

escape from prejudice. In contrast, since other minorities are discriminated

against by ‘others’ (ethnic Japanese), they have a refuge and a distinctive

cultural tradition with which they can identify. Here lies the agony of the

burakumin.

13

Discrimination against burakumin

A number of fabricated allegations surround burakumin and form the basis

for widespread prejudice. Some allege that burakumin are of a different race

(racial origin theory), while others claim that they are of a different ethnic

group (ethnic origin theory). There is also a popular belief that burakumin

ancestors were placed at the bottom of feudal social hierarchy as outcastes

because they engaged in cattle butchering, a practice regarded as unclean and

profane (occupation origin theory). Though the Meiji government issued

the Emancipation Edict in 1871 to abolish the designation as outcastes

and the hereditary occupation system, discrimination against burakumin

continues to this day. The reason behind this rests not only in the fact that

non-burakumin have been very conscious of their feudal status, but also in

186 Hideo Aoki

the reality that discrimination against burakumin has functioned as a lever

for social integration in the process of forming a modern Japan. Behind such

integration is the Buddhist belief that slaughtering animals is an unclean

act,

14

a construct that enables majority Japanese to see themselves as clean

and to form the feeling of collective superiority, solidarity and togetherness.

There is also Japan’s ie system, discussed in chapter 4 of this volume, which

has made it difficult for burakumin to conceal their lineage. Japan’s strict

and elaborate family registration system has enabled all Japanese to access

information on anybody’s genealogical background. Discrimination against

burakumin extends to many areas of their lives, from being rejected as

marriage partners to being discriminated against in job opportunities.

Prejudice, overt and covert, displayed in marriage situations presents the

most serious aspect of buraku discrimination.

15

It is a product of pseudo-

status endogamy, namely, the view that family continuity is highly impor-

tant and therefore so is ‘matched marriage’ in terms of a family’s social

standing and lineage. At the core of such views lies the concept of unclean-

ness, which urges people to prevent the mixing in of base parentage. Some

parents would investigate a potential son- or daughter-in-law’s background

and tear the young lovers away from each other if burakumin ancestry was

revealed. Even those burakumin who managed to marry non-burakumin

did so under difficult circumstances. Some were forced to keep their buraku

parentage a secret, while others were allowed to marry on the condition

that they leave the buraku communities and remain cut off from all contact

with their relatives after marriage.

16

With the influx of foreign workers and

migrants into Japan, international marriages are on the rise. When given

the choice, some parents appear to prefer to see their children married to

foreigners than to burakumin.

17

Similarly, there are some cases in which

landlords have refused to rent their apartments to burakumin, preferring to

lease them to foreigners.

18

Asada Zennosuke, ex-chairperson of the Buraku Liberation League, who

provided the ideological framework underpinning the buraku liberation

movement, summarised the structure of buraku discrimination into three

propositions: (1) its essence – burakumin do not have completely open job

opportunities; (2) its social significance – the low wage levels of burakumin

provides justification for those of workers at large; and (3) discrimination

as social consciousness – prejudice forms in the unconscious levels of per-

ception of the general masses.

19

Burakumin is a relational concept because

one becomes a burakumin by experiencing discrimination as a burakumin;

burakumin become conscious of their status after majority Japanese classify

Buraku culture 187

them (mainly on genealogical grounds). Majority hereditary categorisation

comes before minority consciousness, a process that develops into interac-

tive relationships. To this extent, the changing patterns of discrimination by

majority Japanese alter the substance of buraku community culture.

The forms of discrimination enacted against burakumin have trans-

formed over time. An awareness of equality, which rejects discrimination,

has spread since human rights education was introduced to schools in post-

war Japan. As a result, blatant discrimination based on language and ges-

tures used by non-burakumin decreased. However, prejudiced views which

lie hidden in the depths of consciousness cannot easily be swept away.

Instead, the number of latent and indirect acts of discrimination against

burakumin increased, with new forms of discrimination emerging. In a

number of cases, anonymous individuals and private investigation agen-

cies attempted to acquire burakumin family registers to identify them as

undesirable persons. In one sensational case that became public in 1975,

an underground publication entitled A comprehensive list of buraku area

names, the compilers of which remain unidentified, was secretly sold to cor-

porations and individuals. Many other new ways of conducting background

checks on burakumin have been developed. Also still rampant are graffiti

vilifying burakumin, blatantly discriminatory articles published on the web

and prejudicial language used in the mass media, not to mention unfair treat-

ment in terms of employment, wages, and personnel shuffling.

20

Secrecy,

indirectness, anonymity and insidiousness constitute this trend, as more

complex forms of discrimination and prejudice are faced by burakumin.

21

Buraku culture

While buraku communities have diversified in many ways today, their most

original form is found in those that have the characteristics Inoue Kiyoshi

called trinity: lineage, space and occupation.

22

These communities have spa-

tial boundaries in which burakumin with traceable genealogical background

reside. In such communities, traditional buraku culture flourishes on the

memories of a history of hardship that has been passed on since their days

as outcastes.

Burakumin living in trinity communities generally engage in work in

the industries they specialise in, such as butchery, meat processing and

leatherwork. Most notable is craft such as leather bags, drums and foot

wear – z

¯

ori (Japanese sandals) and setta (Japanese sandals with leather

soles) – and home appliances made from bamboo, straw and wood. In

188 Hideo Aoki

performance art, traditional buraku culture includes harukoma (a congrat-

ulatory dance), shishimai (dance with lion doll), manzai (a comedic art) and

¯

okagura (Shinto music and dance). One can also observe burakumin music,

dance, rituals, folklore, life-skills and even manners and customs that have

been handed down since the feudal period. Much of buraku traditional

culture is derived from a form of folk religion which focuses on worldly

benefits. While, on the one hand, burakumin were despised as outcastes,

they also acted as hafuri (person who controls rituals, such as festivals,

funerals and slaughtering, to purify the unclean things/situation) in charge

of purification rites for the ‘ordinary people’ (farmers who were members

of the general population). Manzai, harukoma, shishimai and the like were

all door-to-door forms of entertainment performed in order to drive away

impurity and taboos.

Contemporary buraku material culture is based on industry that

emerged in response to the new demands of the modern era. This type of

culture derives from work relating to shoemaking, gloves and mitts, bags,

slippers, sandals, processed meat, and the like. Everyday culture is also

created from work relating to small businesses and low wage-labour, such

as construction and public works, car and house wrecking, junk dealing,

garbage and human waste treatment, cleaning and peddling (green vegeta-

bles, sundries, bedding, etc.). Given that these jobs are unstable and poorly

paid, burakumin constantly endure the sense of anxiety involved in engaging

in these occupations. Such anxiety makes the culture of burakumin both

utilitarian and flexible. Since they have not possessed the means of pro-

duction, and have lived the life of low-class labourers, they are inevitably

inclined to take up any opportunities useful for survival, as one burakumin

observed: ‘Who in the world would want to go into the river in the middle

of winter to break off some ice if it wasn’t because they had to?’

23

The arte-

factual culture of buraku communities is also flexible to the extent that their

cultural activities do not require licensing or accreditation, unlike the world

of tea ceremonies and flower arrangements of the middle class Japanese.

Anything that provides sustenance for life is seen as a cultural resource.

For instance, in forms of entertainment such as itinerant performance,

burakumin could engage in these activities without special skills and qual-

ifications. In buraku craft and performing arts, too, the elaborate tech-

niques involved have all been jointly owned and handed down through the

buraku communities, and anyone who is living in dire circumstances can

join without prior qualifications. Burakumin have developed orientations

to usefulness and flexibility, to deal with their plight in a pragmatic fashion.

Buraku culture 189

Finally, burakumin have a culture of pride in their struggle for emanci-

pation. The set of values derived from the pride of their resistance reverses

the values resulting from the miseries of hardship and anxiety.

24

It is

through this aspect of culture that burakumin history and hardships in

life are reinterpreted, reversed, and carved into words, objects, and actions

as symbols of burakumin ‘pride’. Burakumin built their strength to fight

against the difficulties they face by reminiscing about their struggles and

achievements.

These feats include the Emancipation Edict of 1871, which abolished the

status system institutionalised in feudal Japan. The Levellers’ Association

Movement from 1922 to 1942 marked the burakumin’s own political and

collective action that put the issue of equality on the national agenda in

prewar Japan. The All Romance Incident, which developed in Kyoto in

1951, is well known as the first postwar struggle to secure special budgets

from local administrative bodies for the improvement of the conditions of

buraku communities. For many years, buraku movements fought against

discrimination through public denunciation of government officials and pri-

vate citizens who exhibited their prejudice in one way or another. This saw

the government execute a special policy called Measures for D

¯

owa Projects

designed to provide aid to burakumin, though this policy ended in March

2002. The so-called Sayama campaign from 1963 to this day represents a

long struggle to clear the name of an imprisoned buraku member who many

buraku activists and their supporters believe was charged – and has been

falsely imprisoned – only because he was a burakumin.TheD

¯

owa Council

Policy Report of 1965, a landmark achievement of the buraku liberation

movements, enshrined the guidelines for special aid policies for burakumin

and buraku communities.

Self-contradiction in buraku identity

Buraku culture is self-contradictory because of the structural position that

burakumin occupy in Japanese society. On the one hand, buraku culture

is hybrid to the extent that it is both continuous with and distinctive from

Japan’s dominant culture, leaving the borderline between the two cultures

blurred. While buraku culture shares much with non-buraku culture, the

pain of being discriminated against forms the core of buraku existence

which the majority Japanese do not experience, and this shapes the line of

demarcation between the two, making continuity and discontinuity the two

ostensibly contradictory features of buraku culture.

190 Hideo Aoki

On the other hand, buraku culture is double-faceted in the sense that it is

both miserable and proud. It is a culture of misery embodying burakumin’s

poverty, humiliation and alienation; it is a culture of lamentation. ‘There is

nothing good about being born a buraku. Nothing but bad things. In our

case, we couldn’t even get joint worship with the non-burakumin in Haku-

san [a holy mountain]. We couldn’t join the youth association either. The

youth group for the festivals completely ignored us and wouldn’t let us join

in. It’s the same even now.’

25

At the same time, it is also a culture of pride, in

which many burakumin find themselves in their struggle against discrimi-

nation, their pursuit of human dignity and their commitment to liberation.

‘Any foolish person who discriminates against shoemakers must not wear

shoes!’

26

Through the struggle for liberation, many burakumin have found

their pride as human beings: the culture of lamentation transformed into a

culture of pride. ‘I am happy that I was born a buraku because the fighting

spirit has been ingrained in me since young. And because I have learnt that

life is about plowing our own way forward.’

27

Buraku culture, though a marginal one, overturns the values of the

dominant culture. The ‘elegant, fine, and sophisticated’ dominant culture

traditionally holds the ‘vulgar, bold, and simple’ buraku culture in con-

tempt, but burakumin have carried out a kind of ‘symbolic reversal’

28

of

values by putting cultural superiority on the set of values belonging to the

buraku group. Over the centuries they have discovered the beauty in their

lives. Thus, misery and pride sit side by side in buraku culture.

‘The most important aspect of a culture is the way people live – how

people interrelate through their activities in order to survive.’

29

At the core

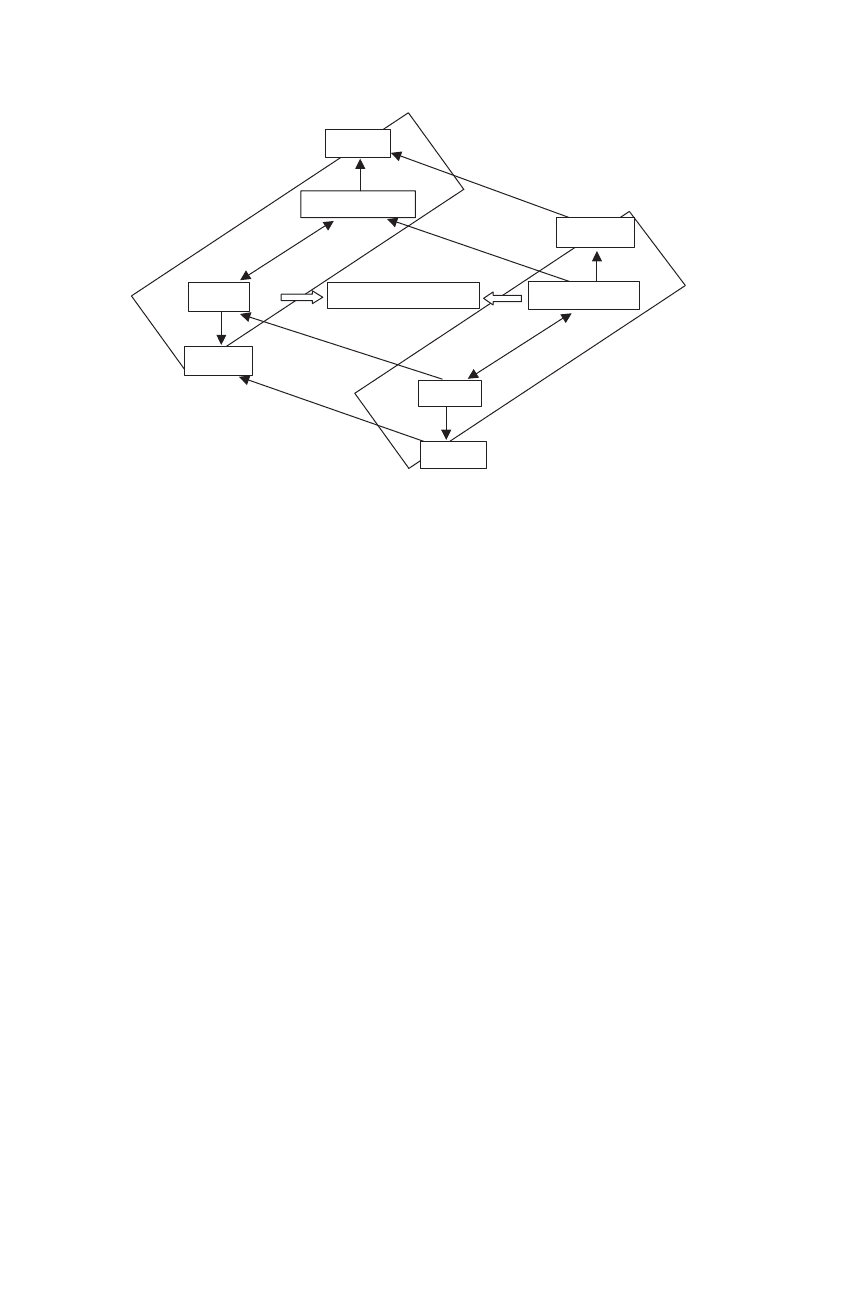

of buraku culture lies burakumin identity, represented in Figure 10.2.

Burakumin identity is partly constructed by memories of history. These

memories are made up of words, objects, and actions of ‘discrimination

and resistance’ and ‘poverty and endurance’. Their identity is also partly

constructed by present everyday life experiences. These comprise the ‘anx-

iety of discrimination and resistance’ as well as the ‘anxiety of poverty and

endurance’. Finally, burakumin compare their everyday life experiences

with their memories of history to gain a collective meaning of anxiety and

resistance. Burakumin identity is formed in this way.

Diversity in buraku culture

Buraku culture adopts diverse forms depending on history, work, life,

and place of residence. The industries of some buraku communities have

Buraku culture 191

Memory of

Historical Hardship

discrimination

reinterpretation

reinterpretation

struggle

resistance

discrimination

Burakumin Identity

poverty

survival

poverty

survival

Experience of

Anxiety of Living

Figure 10.2 Formation of burakumin identity.

developed as a result of government aid while others have not. Some buraku

communities are urban, while others are agrarian or fishing communities.

Urban buraku communities are experiencing an influx of non-burakumin,

while agrarian and fishing buraku communities have ageing populations and

are becoming depopulated as they experience an outflow of young people.

The regional distribution of the buraku communities and their populations

is summarised in Table 10.1 on the next page.

The Kinki region contains many large urban buraku communities. The

Ch

¯

ugoku region is home to numerous small fishing and agrarian buraku

communities. The Ky

¯

ush

¯

u region encompasses a lot of urban and agrarian

buraku communities, its former coal mining areas containing buraku com-

munities which formed in the modern era. The Shikoku region is home to

many small fishing and agrarian buraku communities. The Kant

¯

o region has

numerous small urban buraku communities. Meanwhile, the Ch

¯

ubu region

encompasses many small agrarian buraku communities. Many of the jobs in

the urban buraku communities are in the manufacturing, construction and

service industries, while the construction, agriculture and fishing industries

dominate the fishing and agrarian buraku communities.

Moreover, the levels of activities of the liberation movements differ

from one community to another. The emancipation movements have a

long history in the Kinki region. Some leaders of the outcastes (eta leader

Danzaemon and hinin leader Kuruma Zenhichi) were active in Edo (Tokyo)

192 Hideo Aoki

Table 10.1 Regional distribution of buraku communities and

population

Number of

Region communities Population

Kant

¯

o 572 82 636

Ch

¯

ubu 532 75 455

Kinki 781 372 918

Ch

¯

ugoku 1052 115 565

Shikoku 670 105 612

Ky

¯

ush

¯

u 835 140 565

Total 4442 892 751

Source: Buraku Liberation and Human Rights Research Institute (BLHRRI)

(2001: 736) Survey of Management and Coordination Agency in 1993.

before the Meiji era. Ch

¯

ugoku, Shikoku, and Ch

¯

ubu are coloured by a

history of agrarian buraku community struggle, while Ky

¯

ush

¯

uhasahistory

of joint struggle between the buraku emancipation movements and labour

movements in the 1960s.

Transformation of buraku culture

Discrimination against burakumin has continued over four centuries. Con-

sequently, burakumin and buraku culture have also continued to exist.

However, the nature of discrimination against burakumin has transformed

with time, and as a result, burakumin identity and buraku culture have

transformed too.

In feudal Japan, outcastes were restricted in their choice of occupa-

tion and place of residence. After emancipation in the early Meiji years,

burakumin gained freedom in this regard. At the same time, however, they

lost their exclusive rights to the occupations they had had as outcastes. As

most burakumin did not possess the funds or means to establish new busi-

nesses or change occupations, many of them were forced to take on odd

jobs. They also had little choice but to live in areas that were located in the

places whose habitation environment was inferior.

In more recent decades, buraku communities have undergone trans-

formation, especially as a consequence of economic globalisation. Buraku

communities located in city peripheries and agricultural areas became urban

buraku communities as the cities expanded. Non-burakumin have come

Buraku culture 193

Table 10.2 Types of buraku communities by three factors

Type Community Genealogy Work Comments

Trinity •••Traditional buraku communities.

Genealogical and

Territorial

•• Most buraku communities today,

with no buraku-inherited

industries.

Territorial only • Buraku residents are not burakumin

in a genealogical sense.

Inherited

industries

operating

outside

••Buraku-inherited enterprise moved

out of buraku communities, with

their employees mostly

burakumin.

Dispersal • Isolated burakumin who moved out

of their communities, and their

offspring.

Adapted from Noguchi (2000: 106–17). Two categories in his original table have been

removed because they are analytical categories that are virtually non-existent in reality.

to live among burakumin. Independent buraku industries declined and

burakumin became corporate employees. Finally, the boundaries defining

burakumin became ambiguous as non-burakumin living in the buraku com-

munities were discriminated against, or burakumin were no longer aware

of their origins, and so on.

30

Consequently, the trinity principle consisting

of community, occupation and descent collapsed, leading to the diversifi-

cation of buraku communities in contemporary Japan. Using the typology

of buraku communities that Noguchi Michihiko has developed, one can

identify at least five categories as demonstrated in Table 10.2.

The first type, the trinity group discussed above, represents the ortho-

dox buraku culture but now comprises only a small number of buraku

communities, primarily because of the collapse of the conventional buraku

industries. Yet, these communities are the bedrock of buraku liberation

movements.

The second category, which may be called the residential/territorial type,

forms the numerically largest group. While burakumin in this category

live in identifiable buraku communities, they do not engage in traditional

buraku work, and their occupational structure does not differ much from

Japanese society at large, though the employment of middle-aged workers

tends to be unstable and aged individuals tend to face difficulty in sustaining

themselves. Sharing the historical memories of discrimination and conflict,