Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

for protein is 63 g for males and 50 g for females;

therefore, most American males eat 120% of their

RDA for protein, and American females 158%. This

adds confusion as to whether increases in protein

intake are justified, and some have questioned

whether a chronic high intake of protein could cause

kidney damage or even osteoporosis. Currently, there

are no compelling data to suggest a link with such

damage.

0007 The question of optimal protein intake during

weight gain is controversial; however, alterations in

the levels of fat and carbohydrate, which supply the

bulk of total energy intake, are likely to have greater

effects on weight loss. Some diets, which claim to be

‘high-protein,’ are actually based more on lowering

or eliminating carbohydrate intake and replacing it

with protein and fat energy. These diets will be

discussed below.

Low-carbohydrate Diets

0008 In the 1960s and 1970s, the ‘bad nutrient’ was carbo-

hydrate or, more specifically, sugar. In his 1972 text,

Craddock states, ‘sugar is indeed the great enemy.’

During this time, the low-carbohydrate diet grew out

of the frustration of physicians who had documented

that just telling patients to ‘eat less’ or restrict calories

was not producing positive results. Thus, the notion

of restricting a particular macronutrient, instead of

calories, with free access to other macronutrients was

proposed. Reducing protein intake was illogical, as

protein represents a relatively small proportion of the

total diet. At this time, before the advent of fat re-

placers and low-fat food technology, a diet low in fat

was very unpalatable. This was further reinforced by

the fact that protein and fat both have dietary require-

ments, whereas carbohydrate does not. Reducing

carbohydrate intake from 350 g per day (average

intake) to 50–60 g per day, therefore, seemed to be

the logical nutrient to restrict as a reasonably palat-

able diet could be designed and maintained with

50–60 g of carbohydrate per day.

0009The low-carbohydrate diet encouraged partici-

pants to eat as much as they wanted of foods low in

carbohydrate (meat, fish, cheese, butter, and green

leafy vegetables and 330–670 ml of whole milk per

day). It was assumed that the quantity of these foods

consumed would be similar to the typical intake and,

with the elimination of the carbohydrate energy, pro-

duce a deficit of 3360–4200 kJ (800–1000 kcal) per

day. This energy reduction thus shifted the individual

into a negative energy balance in which increased

levels of fatty acids would be oxidized – or burn fat

– and result in a significant weight loss.

0010Ketogenic diets An extreme form of the low-

carbohydrate diet is a regimen almost devoid of

carbohydrate. This diet encourages ad libitum

consumption of meats, cheeses, eggs, and butter.

Low-starch (mainly water-containing) vegetables

(lettuce, peppers, tomatoes, onions, zucchini) are per-

mitted in limited amounts, depending on the carbo-

hydrate content. Sugars and other monosaccharides

and complex carbohydrate sources (breads, grains,

pasta, rice) or any digestible carbohydrate that

would in turn provoke an insulin response are strictly

restricted.

0011On this diet, glycogen stores are depleted within

24 h, and within 48 h the individual becomes ketotic –

a metabolic state in which glucose is no longer avail-

able in adequate quantities to serve as a fuel. In

ketosis, large amounts of the ketone bodies, aceto-

acetic acid, beta hydroxybutyrate, and acetone, are

produced to be utilized as fuel. These compounds are

produced in the absence of glucose/insulin as a

method to spare glucose for use by the brain and

other solely glucose-utilizing tissues. In the synthesis

of ketone bodies, large amounts of fatty acids from

adipose tissue are mobilized for use as fuel – utilizing

stored fat as energy. In a starvation mode, which the

body believes it is in with a ketogenic diet, the brain

may obtain 30–40% of its energy from ketone bodies.

Ketosis also occurs in uncontrolled diabetes and, if

untreated, can lead to ketoacidosis and coma.

0012The evidence for the effectiveness of very low-

carbohydrate diets is dated as far back as 1932,

when the principle of reducing weight by a diet

‘containing much fat but little carbohydrate’ was

introduced. However, not until the 1950s, following

a series of experiments did low-carbohydrate/high-fat

weight-loss diets begin to emerge in the popular press.

In these experiments, the researchers fed overweight

participants, isocaloric (4200 kJ or 1000 kcal) per

kcal

2

4

6

8

10

Fat Carbohydrate Protein kJ

8

16

24

32

40

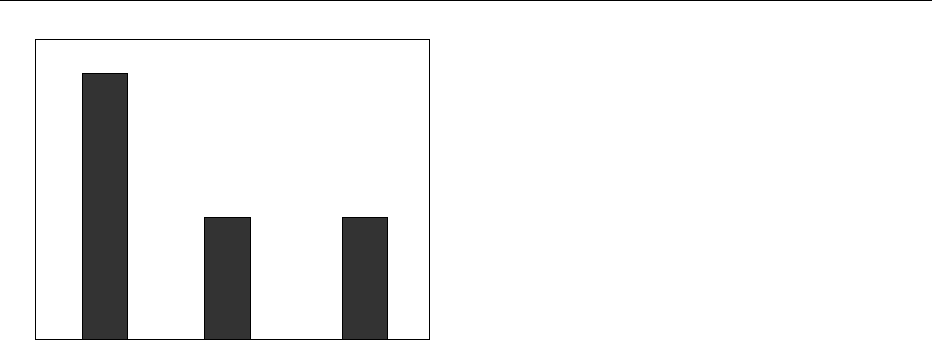

fig0001 Figure 1 Energy content of macronutrients.

SLIMMING/Slimming Diets 5287

day diets comprising 90% protein, carbohydrate,

or fat. Participants lost more weight on the low-

carbohydrate diets (high in fat and protein) than the

high-carbohydrate diet (low in fat). The mean weight

loss on the low-carbohydrate diet was 2.33 kg over 5–

9 days, but there is great intersubject variability with

weight losses ranging from 0.6 to 3.2 kg. Also, the

duration of the diet periods (5–9 days) is too short to

adequately assess this diet composition on long-term

weight loss. Further, it is well established that each

gram of muscle glycogen that is converted to glucose

for use as fuel yields 3 g of water. Thus, it is theorized

that during the initial stages of a low-carbohydrate

diet, when glycogen stores are being depleted, much

of the weight loss is from water loss.

0013 Some follow-up studies compared low-

carbohydrate diets with low-fat diets and investigated

the amount of weight and water loss on each regimen.

One study showed that there was no significant dif-

ference in the rates of weight loss on either diet. In

addition, when these diets were interchanged, devi-

ations from the weight-loss curve occur mainly as a

result of fluid balance. Another study found that a

high-fat/low-carbohydrate diet resulted in weight

loss, but the weight loss ceased after a few days and

was explained largely by fluid loss. However, a study

in 1981 measured sodium, potassium, and water

losses on diets low or high in carbohydrates over a

28-day period and found conflicting results. In this

study, although sodium and potassium losses were

greatest on the low-carbohydrate diets (at least until

day 14), water losses showed no significant differ-

ences at any time period, and the low-carbohydrate

diet produced a significantly greater weight loss

than the high-carbohydrate diet (12.5 + 0.9 kg and

9.5 + 0.7 kg).

0014 Recent studies The 1990s saw a resurgence in the

popularity of low-carbohydrate diets, and with it,

new research has emerged. In a 1996 study, 43

obese participants were randomly assigned to con-

sume diets of equal energy but which differed in

macronutrient composition:

.

0015 low-carbohydrate diet: 32% protein, 15% carbo-

hydrate, 53% fat;

.

0016 low-fat diet: 29% protein, 45% carbohydrate,

26% fat.

Similar to the studies done in the 1960s, this study

found that weight, plasma glucose, cholesterol, and

high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol changes were

similar on both diets. Interestingly, however, the

higher-protein/fat, lower-carbohydrate diet was

found to be more beneficial on plasma insulin and

triacylglycerides (triglycerides). It is important to

note that this diet was not ketogenic, as were diets

fed to the participants of the earlier studies. These

results were consistent with other, more modern

studies.

0017The current view of ketogenic low-carbohydrate

diets is that at least 100 g per day or more of carbo-

hydrate is recommended both to spare protein and to

avoid large shifts in weight resulting from changes in

water balance and electrolyte loss. When carbohy-

drate levels are below 100 g per day, insulin levels

fall, and protein is catabolized to provide the gluco-

genic amino acids. Most diets providing under 100 g

per day of carbohydrate or approximately 3360 kJ

(800 kcal) per day are ketogenic. Also, dieters may

have negative side-effects, including fatigue, postural

hypotension, a fetid taste in their mouths (from

increased acetone production), and elevated serum

uric acid levels, and may be more subject to negative

nitrogen balance. In addition, because consuming a

low-carbohydrate diet often means consuming a diet

higher in fat, cardiovascular health is of concern. A

high intake of saturated fat, found mainly in meat and

dairy products, has been linked to increased serum

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and is thus

thought to be atherogenic; however, the beneficial

effects of low-carbohydrate diets on insulin and tri-

glyceride levels should not be dismissed. High trigly-

ceride levels have begun to receive increased attention

in medical research as a serious cardiovascular dis-

ease risk factor. Low carbohydrate diets which obtain

the majority of protien from vegetable protein (nuts,

soy, legumes) should be more healthful overall, but

more research is needed.

0018Low-glycemic index diets Recent research focus

has shifted away from low-carbohydrate diets to

‘low-glycemic index’ diets. The glycemic index was

proposed by Jenkins to characterize the rate of carbo-

hydrate absorption after a meal and is defined as the

area under the glucose response curve after consump-

tion of 50 g of carbohydrate from a test food divided

by the area under the curve after consuming a control

food (usually glucose). The glycemic index of foods

became of interest as dieters following a low-fat regi-

men began replacing fat calories with carbohydrate

calories. Many of the foods chosen to replace high-fat

foods were high-glycemic index foods (Table 2). To

compound this situation, ingested fat serves to slow

the rate of absorption of concomitantly ingested

carbohydrate. Thus, some researchers believe that

low-fat diets have resulted in an increased intake of

high glycemic index foods that are more rapidly

absorbed, thus causing a functional hyperinsuline-

mic response. This hyperinsulinemic state may pro-

mote weight gain by preferentially directing nutrients

5288 SLIMMING/Slimming Diets

away from oxidation in muscle and toward storage

in fat.

0019 A number of studies have examined the effects of

glycemic index on appetite and food intake regulation

in humans. Two studies found lower blood glucose

levels and a slower return of hunger after low-

glycemic index meals compared with high-glycemic

index meals. Another study investigated the hormo-

nal response to high- and low-glycemic index foods.

This study provided obese teenage boys low-,

medium- and high-glycemic index meals. Relatively

high insulin and low glucagon concentrations were

observed following the high-glycemic index meal.

Such hormonal changes would be expected to pro-

mote uptake of glucose in muscle, liver, and fat tissue,

restrain the release of glucose, and inhibit lipolysis

(release of fatty acids for fuel). In addition, a ‘reactive

hypoglycemic’ period was observed following the

high-glycemic index meal – high insulin levels effect-

ively cleared the abundant blood glucose and lowered

free fatty acid concentrations 3–5 h after the high

glycemic index meal compared with the low-glycemic

index meal. In this metabolic state, stimulation of

appetite would be expected. Indeed participants con-

sumed more energy after the high-glycemic index

meal compared with the medium- or low-glycemic

index meals. Thus, hormonal responses to a high-

glycemic index diet appear to lower circulating levels

of metabolic fuels, stimulate hunger, and favor stor-

age of fat, events that may promote excessive weight

gain if excess energy is consumed. A diet of low-

glycemic index foods would include abundant quan-

tities of vegetables, fruits, and legumes, moderate

amounts of protein and healthful fats, and decreased

intake of refined grain products, potato, and concen-

trated sugars.

Low-fat Diets

0020 In contrast with the dated research done on low-

carbohydrate diets, research on the effects of low-fat

diets is more recent. Until the mid-1980s, there were

few studies examining the effects of variations in the

level of fat in the diet on energy intake and body

composition. This was because, before this time,

there was relatively little emphasis on the role of

dietary fat in obesity and related disease states. Re-

search from the 1980s suggested that the oxidation of

protein and carbohydrate is closely tied to their

intake, whereas fat oxidation is not closely correlated

with intake. This suggests that fat, unlike the other

macronutrients, does not promote its own oxidation,

and to maintain fat balance, fat should be con-

sumed in small amounts or coupled with behav-

iors that promote fat oxidation, such as aerobic

exercise.

0021This work, coupled with several low-fat feeding

trials (discussed below), effectively shifted the em-

phasis from sugar to fat as the ‘bad’ nutrient. Food

manufacturers followed this trend by producing a

large number of products that were low-fat or fat-

free versions of traditionally higher-fat foods. The

development of a number of functional, fat-replacing

ingredients allowed food technology to develop pal-

atable low-fat/no-fat foods in a range of food categor-

ies. However, although there have been a number of

studies on the role of dietary fat in the etiology of

obesity, there have been few well-controlled studies

on diet composition and weight loss. Surprisingly,

there are almost no data on the effects of fat-replaced

foods on weight control.

0022Three large, controlled, laboratory studies from the

1980s and early 1990s investigated the effects of

covert manipulations of the fat content of a diet con-

sumed ad libitum on energy intake and body weight.

In a study in 1983, participants were fed a low-fat

diet comprising traditionally low-fat foods (fruits,

vegetables, and grains) and a high-energy-density

diet for 5 days. Participants could eat the foods freely

or ad libitum. Participants reduced their energy

intake by half when eating the low-fat diet compared

with the high-fat diet [12 552 kJ (3000 kcal) vs.

6569 kJ (1570 kcal) per day]. However, no data

were reported regarding weight loss.

0023Two other studies, conducted at Cornell University,

are often cited in both scientific and popular literature

as proof that ad libitum consumption of low-fat foods

can reduce fat intake and lead to weight loss. In the

first of these studies, overweight participants were

each fed three diets: low-fat 15–20%, medium-fat

30–35%, and high-fat 45–50% of energy. Energy

consumption increased as the level of fat of the diet

increased, with the low-fat diet resulting in an average

reduction of 2205 kJ (527 kcal) per day compared

with the high-fat diet. Despite these daily differences,

the diets did not produce any statistically significant

weight changes over the 2-week periods. The second

Cornell study was similar but extended the interven-

tion period to 11 weeks. In this study, participants

consumed an average of 1201 kJ (286 kcal) per day

less on the low-fat diet than on the high-fat diet.

Weight loss was significantly greater on the low-fat

diet than on the high-fat diet, but weight loss occurred

on both diets, making it difficult to conclude that the

low-fat diet was more effective for weight loss. In

addition, although statistically significant, the actual

weight losses are quite small. This evidence indicates

that low-fat diets consumed ad libitum may be some-

what useful for reducing the amount of fat consumed

– important for cardiovascular health, but their effect-

iveness for weight loss is less impressive.

SLIMMING/Slimming Diets 5289

0024 Another study examined the weight loss potential

of restricting fat plus caloric intake compared with

restricting just fat intake. Over the 16–20 weeks

of treatment, the group with energy restriction lost

significantly more weight (males 11.8 kg, females

8.2 kg) than the group only modifying fat intake

(males 8.0 kg, females 3.9 kg). There was also a sig-

nificantly greater loss of body fat in the energy restric-

tion group. The authors concluded that it is more

effective to instruct overweight persons to restrict

both fat and energy intake than it is to restrict only

fat intake as a weight loss strategy. Finally, a study

from the US Department of Agriculture investigated

the effects of varying the fat level of a reduced-energy

diet on body weight and composition. In this study,

the fat content of the diet of eight overweight males

fed at 50% of maintenance was manipulated. No

significant differences were found between the low-

fat and high-fat diets in the extent or composition of

body-weight loss. Body weight decreased by 5.2 kg

for the high-fat group and 5.0 kg for the low-fat

group. Subjects in the low-fat group, however, did

lose more fat and less fat-free mass than did the

high-fat groups. This research implies that weight

loss is not dependent on the composition of the diet

as long as the diet is reduced in total energy.

0025 These studies taken together indicate that, al-

though fat restriction may be of some use for weight

loss, restricting total energy intake is the most import-

ant factor. The results regarding energy deficit and

diet composition are consistent with other research

reports that state that the most significant factor de-

termining the amount and rate of weight loss is the

degree of negative energy balance achieved. It may be

that low-fat diets are most useful in preventing excess

energy intake and obesity. There has never been a

single study showing an advantage of high-fat diets

over low-fat diets in reducing energy intake and pre-

venting obesity. For the same reasons, fat restriction

may also be beneficial as part of a weight-loss main-

tenance program.

Low-energy-density Diets

0026 Another impediment to weight loss is the abundant

availability of an energy-dense diet in Western cul-

ture. Energy density is a measure of the amount of

energy in a given weight of food. It is reasonable

to assume that when foods are more heavily packed

with energy, even small portions can produce large

energy intakes and increase the probability of occur-

rence of periods of positive energy balance. What

may be key is reducing the overall energy density of

the diet.

0027 Energy-dense foods include those that are high in

fat, those with large amounts of added sugars

or processed flours, and those low in water. Some

fat-replaced foods, sweet, and other snacks can have

large amounts of added sugars/processed flours,

making them low in fat, but also energy-dense. Be-

cause both high-fat foods and high-glycemic index

foods are energy-dense; choosing foods less dense in

energy may bring these philosophies together. Energy

density is affected by the fat content of food, and

processed flours contribute to energy density because

large amounts of these nutrients can be incorporated

into foods and not diluted with water, as in naturally

occurring foods. Because it increases the weight of

food but not the energy content, the amount of

water in a food also greatly affects energy density.

Fiber in foods holds a large amount of water and

can provide a sensation of fullness in the gut.

0028The studies described in the low-fat diet section

also illustrate the utility of a diet lower in energy

density. Individuals in those studies tended to eat a

constant weight of food. When the food consumed

was lowered in energy-density, the same weight of

food supplied fewer calories. It has been demon-

strated that individuals tend to eat a constant weight

of food, rather than eat a constant amount of any

of particular macronutrient or amount of energy.

Another study allowed lean women to consume

ad libitum three different diets that varied in energy

density but had constant amounts of carbohydrate,

fat, and protein. The women also tended to eat the

same amount or quantity of food but consumed 30%

less energy on the low-energy-density diet.

0029In selecting foods appropriate for a low-energy-

density diet, it is difficult to reduce the energy density

of the diet without decreasing fat and added sugar

intake and increasing dietary fiber intake, bringing

together some principles of the low-fat and low-

glycemic index philosophies.

Conclusions

0030It is clear, with the large number of individuals meet-

ing the overweight and obese criteria at this time and

attempting to diet, that weight loss is not simple or

easy. It is also clear that no one dietary principle is

applicable to all individuals. It may be that genetic

influences such as those that influence fuel utilization,

glucose metabolism, fat storage, etc., may make the

restriction of one macronutrient result in a more sub-

stantial weight loss for one person while being less

effective for another. The impact of genetic differ-

ences on the effectiveness of pharmaceutical products

has received great attention recently, and such differ-

ences are being explored from a nutritional perspec-

tive as well. It may be that future dietary treatment

for weight loss will be based (at least partially) on

5290 SLIMMING/Slimming Diets

one’s individual genome to optimize diet manipula-

tion effects and maintain/restore maximal health.

0031 At present, the most beneficial aspect of altering

the composition of the diet in terms of weight control

may be that the alteration simply results in less energy

being consumed. The data presented here, however,

indicate that diet-composition changes alone are in-

sufficient for significant weight losses. Weight loss is

dependent upon creating a negative energy balance,

which can be achieved in part by diet-composition

changes but also must include reductions in overall

energy intake.

0032 Because eating patterns, personal habits, and food

likes and dislikes vary so greatly between individuals,

an individual seeking a weight-loss plan must decide

which approach to reducing energy intake is best

suited for their lifestyle. If an intake pattern can be

established and maintained in which less energy is

being consumed than oxidized, weight loss will

occur. Weight loss will generally occur in proportion

to the degree of energy restriction and the duration of

that energy restriction.

0033 The next level of concern regarding weight loss is

the secondary effects of the weight loss diet on health

and whether that diet is palatable and sufficient in

nutrients so that it can be maintained long enough to

produce the desired weight loss. From a health stand-

point, reducing saturated fat remains supported by

the literature, whereas following a diet very low in

fat may not be, especially if healthy fats (such as

monounsaturated fats and omega-3 fatty acids) are

restricted. In addition, fat should not be replaced with

high-glycemic index foods. The data for a hyperinsu-

linemic response following ingestion of high-glycemic

index foods and the subsequent effects on energy

storage and appetite are compelling. Ketogenic diets,

however, are associated with few health benefits,

other than reduced blood glucose and insulin –

which, most likely, will not be maintained once

carbohydrates are reintroduced.

0034 So what is the healthiest method by which to

reduce energy and lose weight? The concept of redu-

cing the energy-density of the diet by decreasing

consumption of high-fat/high-energy foods (cheese,

bagels, butter, fried foods, some dairy products) and

increasing consumption of low-energy dense foods

(vegetables, fruits, legumes, and high-fiber foods)

may be the best prescription for overall health.

Health effects of increased intake of dietary fiber

include reduced blood glucose levels and cholesterol

as well as a balanced gastrointestinal function. The

addition of healthy fats in moderate amounts should

also be considered; however, even healthy fats are

high in energy – thus, smaller portion sizes may be

needed to reduce energy when such fats are included.

A low-energy-density diet should result in a reduced

energy intake and produce a steady weight loss unless

unusually large portions are consumed.

See also: Carbohydrates: Classification and Properties;

Energy: Measurement of Food Energy; Intake and Energy

Requirements; Measurement of Energy Expenditure;

Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance; Fats:

Requirements; Glucose: Glucose Tolerance and the

Glycemic (Glycaemic) Index; Ketone Bodies; Snack

Foods: Range on the Market

Further Reading

Atkins RC (1998) Dr. Atkins New Diet Revolution. New

York: Avon Books.

Burton-Freeman B (2000) Dietary fiber and energy regula-

tion. Journal of Nutrition 130: 272S–275S.

Hill JO, Melanson El and Wyatt HT (2000) Dietary fat

intake and regulation of energy balance: implications

for obesity. Journal of Nutrition 130: 284S–288S.

Ludwig D (2000) Dietary glycemic index and obesity. Jour-

nal of Nutrition 130: 280S–283S.

McCrory M, Fuss PJ, Saltzman E and Roberts S (2000)

Dietary determinants of energy intake and weight

regulation in healthy adults. Journal of Nutrition 130:

276S–279S.

Rolls BJ (2000) The role of energy density in the overcon-

sumption of fat. Journal of Nutrition 130: 268S–271S.

Rolls BJ and Barnett RJ (2000) The Volumetrics Weight

Control Plan: Feel Full on Fewer Calories. New York:

Quill.

Rolls BJ and Hill JO (1998) Carbohydrates and Weight

Management. Washington DC: ILSI Press.

Sears B and Lawsen B. The Zone: A Dietary Road Map to

Lose Weight Permanently: Reset Your Genetic Code,

Prevent Disease: Achieve Maximum Physical Perform-

ance. New York: HarperCollins.

Simopoulos AP and Robinson J (1999) The Omega Diet:

The Lifesaving Nutritional Program Based on the Diet

of the Island of Crete. New York: HarperCollins.

Metabolic Consequences of

Slimming Diets and Weight

Maintenance

E Rasio,Ho

ˆ

pital Notre-Dame, CHUM, Montreal,

Quebec, Canada

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001In many societies today, a plethora of individuals

pursue weight reduction diets for a variety of reasons,

SLIMMING/Metabolic Consequences of Slimming Diets and Weight Maintenance 5291

ranging from social pressures to medical concerns.

Dieters usually fail to perceive that the phenomena

underlying weight gain and weight loss may be quite

different in complexity. Weight gain, as a conse-

quence of excess energy intake, is a relatively simple

process whereby fat stores are increased. To a large

extent, it is independent of the quality of food eaten.

Thus, whenever calories are ingested in excess of

calories expended, be they in the form of sugars,

proteins, lipids, or alcohol, the balance is stored in

the most compact, weight-efficient form, as fat. The

only exceptions to this rule are growth, pregnancy,

muscle building, and rehabilitation following malnu-

trition, where excess calories, with adequate amounts

of protein, can also be retained as protein.

0002 Weight loss, as a consequence of insufficient energy

intake, has a greater variety of effects which depend

upon nutritional status, energy content of the diet,

and balance of nutrients. Thus, an excess daily intake

of 1250 kJ (300 kcal) in the form of 75 g of sugars, or

75 g of protein, or 35 g of lipids, will result, in most

individuals, in a gain of 35 g of body fat. A deficient

daily intake of energy of 1250 kJ may induce a con-

siderable range of changes in body weight and body

composition. In appropriately chosen conditions, the

subject will lose 35 g of body fat, but electrolytes

and protein shifts will often alter the body weight

response so that not all of the weight lost will be in

the form of fat. (See Energy: Energy Expenditure and

Energy Balance.)

Regimens for Weight Control

0003 The ideal diet should deplete body fat stores, which

are excessive, without reducing the protein pool out

of proportion to the small increment always associ-

ated with the obese state itself. For this to occur, the

chosen diet should meet stringent qualitative and

quantitative requirements. Brain metabolism requires

150 g of glucose per day: with the exception of pro-

longed fast when ketone acids can be oxidized, the

need for glucose is mandatory and cannot be met by

transformation of lipids, whether supplied by the diet

or mobilized from body reserves. Glucose can be

generated from protein, from the glycogen pool, or

provided in the diet. Consequently, diets which pro-

vide at least 2500 kJ (600 kcal) per day in the form of

carbohydrate, and a substantial portion of protein,

will spare the waste of endogenous protein and mo-

bilization of the glycogen pool. Many slimming diets

do not satisfy the brain’s need for glucose, and there-

fore deplete glycogen and protein stores. These diets

may be grouped into first, total fasting and certain

very-low-calorie diets, or ‘modified fasts,’ which do

not contain enough glucose and protein precursors,

and second, diets which supply adequate calories but

mostly in the form of fat. With both groups of diets,

body proteins are mobilized and converted by the

liver to glucose, which is then oxidized by the brain.

The loss of body protein entails a loss of weight

which is 10 times that of adipose tissue for an

equivalent calorie content. A total fast will induce a

protein loss not too dissimilar to that of a 5000 kJ-

per-day diet, composed mainly of fat. In both

instances, the weight loss will be very important:

the high-weight-low-calorie protein waste will over-

whelm the low-weight-high-calorie changes of fat

stores. Concurrent major fluid losses will compound

the phenomenon. (See Carbohydrates: Digestion,

Absorption, and Metabolism; Requirements and

Dietary Importance; Fats: Digestion, Absorption,

and Transport; Requirements.)

0004Dietary strategies other than a reduction in calorie

content have not been thoroughly evaluated for the

treatment of obesity. There is some evidence that

macronutrients may act directly, by their nature

rather than energy, on mechanisms which regulate

body weight. Furthermore, the potential of micro-

nutrients to affect fat storage has not been explored.

0005Behavior modification targeted at overeating is

also advocated to help reduce body weight. Some

obese individuals may suffer from specific behavioral

syndromes characterized by excessive consumption of

certain foods, at particular times, e.g., carbohydrate

cravings have been associated with seasonal affective

disorders.

0006The major obstacle to dietary and behavioral treat-

ment of obesity is that the voluntary control of energy

intake is difficult and requires strong motivation.

This is particularly true in affluent societies where

food is plentiful and varied. The success rate of

dieting can be disappointing: studies published in

the medical literature indicate that weight loss after

1 year is usually less than 10% of entry weight. How-

ever, most people who determine that they should

control their weight, or are advised to do so, are

never part of medical surveys. Thus the real success

rate for populations are not known.

Metabolic Consequences of Weight-

reducing Diets

Negative Nitrogen Balance

0007Whenever a diet, irrespective of its calorie content,

does not have sufficient protein to maintain required

rates of protein synthesis, or a sum of protein and

carbohydrate to meet the brain’s energy require-

ments, it will induce a negative nitrogen balance,

with protein tissue waste. Obese individuals have an

5292 SLIMMING/Metabolic Consequences of Slimming Diets and Weight Maintenance

increased lean body mass and a higher metabolic rate

than control individuals of ‘ideal’ body weight.

Therefore, protein waste will be tolerated to some

extent during dieting. Unfortunately, there is no evi-

dence that protein is lost from those tissues where it

accumulated during weight gain, i.e., from adipose

tissue as a consequence of cell hyperplasia and hyper-

trophy, and from muscle and supporting tissues as a

response to increased gravity. On the contrary, the

protein loss may occur from all tissues. The digestive

tract and the heart are particularly prone to func-

tional alterations. In conditions of excessive negative

nitrogen balance, thinning of the skin and loss of

brain tissue have been reported.

Water and Electrolytes Losses

0008 Elimination of excess water is a common feature of

weight loss, particularly during the early stages. A

negative calorie balance reduces insulin secretion

and has a diuretic effect which enhances weight loss

beyond that expected from endogenous fat oxidation.

The diuretic effect varies with the quantity and

quality of energy consumed. In general, the lower

the energy content as carbohydrate, the greater the

diuretic effect. Concurrent loss of sodium and potas-

sium in the urine reflects the contraction of the

extracellular and intracellular water compartments.

Cardiac arrhythmia, including ventricular fibrillation

and death, have been reported, probably as a conse-

quence of electrolyte changes in the serum and cells.

The use of diuretics alone or in combination with

diets, especially when markedly carbohydrate-

restricted, is therefore dangerous or, at least, superflu-

ous in the treatment of uncomplicated obesity.

Before counteractive adaptive mechanisms are set

in motion, water loss at the initiation of low-calorie-

low-carbohydrate diets may induce an extra weight

loss of 0.5 kg per day, or even more. (See Water:

Physiology.)

0009 Water loss will confound changes in body fat

weight. In extreme situations, such as those created

by regimens very high in calories and fat, protein

waste and dehydration will induce weight loss while

fat stores are actually increased. Other diets, along

the same principles, will also reduce weight with little

fat loss.

Lowering of Blood Pressure

0010 Overeating stimulates the release of catecholamines

and insulin. Consequently, renal reabsorption of

sodium is increased, and higher blood volume and

cardiac output may then raise blood pressure. Hypo-

caloric diets will reverse this sequence of events and

frequently reduce the hypertension associated with

obesity, without medication or sodium restriction.

(See Hypertension: Physiology.)

0011Weight-reducing diets, in particular those low in

carbohydrate, induce relaxation of arteriolar tonicity

and lowering of diastolic blood pressure. This, in

combination with fluid volume contraction men-

tioned above, is responsible for orthostatic hypo-

tension, a frequent side-effect, characterized by the

inability to redistribute blood from the lower limbs

when standing. Salt supplementation can diminish

such an effect, but not abolish it, as a new steady

state is reached in which the extra sodium is simply

excreted. (See Hypertension: Hypertension and Diet.)

Lowering of Blood Lipids and Glucose

0012Although most obese individuals are free of metabolic

complications such as dyslipoproteinemias and non-

insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, many patients

with these metabolic anomalies are obese. When

energy and carbohydrate intake are excessive, high

levels of triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol may accumulate in plasma. Obesity is

also often associated with a diminution of circulating

high-density lipoproteins. These changes in plasma

lipid composition will contribute to the development

of atherosclerosis and increase the risks of cardio-

vascular disease. Hypocaloric diets can rapidly blunt

or eliminate hypertriglyceridemia, by the plasma-

clearing action of lipoprotein lipase, and hypercholes-

terolemia, by reducing both the endogenous and

exogenous flow of atherogenic lipoproteins. Con-

comitantly, the level of high-density lipoproteins in

the plasma increases. Weight reduction can therefore

often help to control dyslipoproteinemia without the

use of pharmacological agents. (See Atherosclerosis;

Lipoproteins.)

0013Blood glucose abnormalities in obese subjects are

frequent. They range from mild glucose intolerance to

overt noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. These

anomalies of glucose homeostasis are characterized

by the presence of normal-to-high levels of circulating

insulin which are insufficient to overcome the resist-

ance by target tissues to its biological effects. Excess

plasma insulin is a potential, albeit still controversial,

risk factor for atherosclerosis. One of the most im-

pressive effects of energy-restricted diets is the im-

provement or normalization of the altered glucose

homeostasis associated with obesity. In a matter of

days, even without significant losses of body weight,

the obese subject can be switched to a normal glucose

metabolism. A negative calorie balance can rapidly

restore insulin sensitivity in a dieting individual. The

mechanisms of this spectacular metabolic regulation

are not known. The treatment of diabetes in the

obese requires oral hypoglycemic agents only when

SLIMMING/Metabolic Consequences of Slimming Diets and Weight Maintenance 5293

energy-restricted diets have proved unsatisfactory. In-

sulin may also be required to control blood glucose

levels, in spite of possible atherogenic changes of the

plasma lipid profile.

Reduced Resting Metabolic Rate and Postprandial

Thermogenesis

0014 With the loss of significant amounts of body weight,

oxidative metabolism decreases, as does energy

expenditure. This occurs both at rest and following

meals. At rest, most of the energy produced is utilized

to maintain body temperature and vital processes.

Following the ingestion of a meal, additional oxygen

is required for mechanical work associated with di-

gestion, and for chemical reactions involved in pro-

cessing the nutrients. The energy cost of disposing of

food in the body varies with the caloric content of the

meal, its composition, and sapidity. It represents only

a small percentage of the overall resting metabolic

rate. The main factors responsible for slowing of

the oxidative metabolism are hormonal adaptive

changes. Faced with reduced energy intake, the body

responds by lowering the circulating levels of hor-

mones which stimulate energy expenditure. Thus,

the activity of the sympathetic nervous system is di-

minished and catecholamine production is lowered.

Furthermore, the conversion of the thyroid hormone

thyroxine into the more powerful hormone triiodo-

thyronine is also reduced. These changes combine

their effects in reducing mitochondrial oxidation

and, therefore, energy output. This adaptive sparing

of body weight varies with the energy restriction and

the composition of the diet. It may represent approxi-

mately 850 kJ (200 kcal) per day after 2–3 weeks of

fasting, but less if the diet has energy, particularly in

the form of carbohydrates. Finally, when significant

glycosuria is present in obese diabetic patients, the

rapid lowering of blood glucose levels at the start of a

hypocaloric diet will reduce or abolish the glucose

caloric output in the urine and slow down weight

loss accordingly. On the other hand, exercise, by

implementing energy expenditure and by blunting

the drop in metabolic rate associated with a negative

energy balance, enables the weight loss to continue

unmitigated. (See Hormones: Thyroid Hormones;

Thermogenesis.)

0015 A more chronic effect of weight-reducing diets is

the loss of significant amounts of body weight when

lean tissue is also wasted. The ensuing cell atrophy

will contribute to lowered oxygen consumption.

Patterns of Weight Loss

0016 After the initiation of a hypocaloric diet, a combin-

ation of behavioral and metabolic mechanisms takes

place wherein the rate of weight loss decreases with

time, despite a constant dietary intake.

0017On the behavioral side, many dieters tend to reduce

their energy expenditure as a reflex in the face of

scarce energy intake. Probably the most common

cause for plateaus in weight loss is that, even with

adherence to appropriate pattern and composition of

the diet, portion sizes tend to increase.

0018On the metabolic side, a number of predictable

adaptive reactions slow the rate of weight loss. First,

water and electrolyte losses are rapidly blunted

by sensitive hormonal counterregulatory responses.

These may involve, depending upon the degree of

water loss, the liberation of antidiuretic hormone by

the hypothalamus or the stimulation of the renin–

angiotensin–aldosterone axis. These responses are

more decisive when diuretics are prescribed with the

diet. Second, the body adapts by shifting its oxidative

metabolism from glucose to fat and ketone acids. The

reduced need for glucose spares the energy-diluted

protein tissue at the expense of the energy-dense fat

stores. Thus, the rate of body weight loss declines to

very near the theoretical level expected from conver-

sion to fat as the primary source of energy utilization.

Third, the oxidative metabolism diminishes pari

passu with the activity of the thyroid gland and sym-

pathetic nervous system. Fourth, the loss of lean body

mass, with time, lowers the resting metabolic rate,

thus reducing the energy deficit.

0019Occasional interventions in the course of dieting

may also slow down the rate of weight loss. Rotating

diets, depending on their sequence, may induce rapid

shifts in water and protein pools. For example, when

a 3500 kJ per day ketogenic diet is followed by a diet

of the same calorie content but richer in carbohydrate

and protein, the weight loss may be temporarily re-

duced and weight may even increase as a consequence

of water and protein gains. This same diet would have

the opposite predictable effects if administered de

novo. Thus, the same hypocaloric diet is capable of

inducing either weight and protein gain, or weight

and protein loss in the same individual, depending

on the previous metabolic balance at any given total

body weight. These considerations emphasize the

extent to which the dependence of the dieter upon

body weight measurement as a source of feedback

information can be misleading.

0020A less common but interesting situation is created

when dieting individuals embark on exercise pro-

grams. This leads to loss of body energy, without the

expected concurrent loss of weight. It is possible, for

example, to lose 1 kg of body fat as a consequence of

a negative calorie balance, and to gain 1 kg of tissue

protein as muscle is built up. The body weight has not

changed, but the individual has lost in the process

5294 SLIMMING/Metabolic Consequences of Slimming Diets and Weight Maintenance

30 000 kJ of body energy. Recent studies have shown

that a similar protein-sparing effect, with negative

calorie balance, can be achieved by administration

of appropriate doses of insulin or growth hormone.

The usefulness of these hormonal manipulations in

the dieting individual has not yet been established.

Maintenance of Weight Loss

0021 Whenever the stability of body weight is disrupted,

the hypothalamic counterregulation will tend to

restore weight to its initial value. This phenomenon

applies in general to any level of weight equilibrium,

whether the subject is thin, of ‘ideal’ weight, or obese;

it is also operative for whichever direction the change

of weight takes place, be it a gain or a loss. It is

therefore recommended, in order to overcome the

constraints of the ‘ponderostat,’ that slimming strat-

egies aim for a moderate rather than rapid rate of

weight loss, interspersed with periods of weight

stabilization.

0022 Physical exercise has the ability, within a wide

range of intensity, to maintain and possibly

reestablish the regulatory functions of the brain con-

cerning energy balance. Exercise programs should

therefore complement the slimming diet, with the

reasonable expectation that they will help the dieter

to maintain the weight loss.

0023 The temporary use of anorectic drugs has been

advocated to promote weight maintenance between

episodes of weight loss. The administration of thyroid

hormones, to offset their lowered secretion during

weight loss, or to raise their plasma levels to the

high range of normal values during weight stabiliza-

tion, is likely to increase nitrogen loss. Drugs designed

to reduce the intestinal absorption of carbohydrates

or lipids may prove beneficial in weight maintenance

programs, when dieters tend to regain weight. Today,

there is not sufficient evidence to recommend the

regular use of any of these pharmacological agents.

0024 Finally, therapies intended to improve the will

to lose weight are an essential part of slimming

programs. Group support therapy, as provided by

associations such as Weight Watchers, or individual

psychotherapy, may be successful in some individ-

uals, while knowledge of nutrition principles seems

to improve the incentive to lose weight and maintain

the loss.

Benefits of Exercise

0025 Exercise has many beneficial effects for weight main-

tenance. The most acknowledged effect, albeit not the

most important, is that exercise increases calorie

expenditure above the resting metabolic rate. The

energy cost of exercise is often overestimated by

dieters and easily annulled by food self-reward. For

example, a brisk 1-h walk has approximately the

equivalent energy of three small slices of bread.

0026Exercise, of some intensity and frequency, has

anorectic properties that are probably mediated by

changes in hypothalamic neurotransmitters and sex

hormone production. With more moderate ranges of

physical activity, as previously stated, the hypothal-

amic regulation of energy balance seems to be better

able to adjust energy intake to energy expenditure on

a day-to-day basis, thereby improving the chances of

weight maintenance.

0027Exercise has powerful effects on fuel utilization in

general and glucose metabolism in particular. Acute

exercise accelerates the net rate of glucose utilization

through the actions of humoral and hormonal factors

on adipose tissue, muscle, and liver. The blood

glucose-lowering effect of exercise may be rapid and

important. It mimics the effect of intravenous injec-

tions of significant amounts of insulin, with the added

characteristic that it manifests itself in most instances,

whether the subject is insulin-resistant or not.

Furthermore, chronic exercise counteracts insulin re-

sistance associated with obesity, hence improving glu-

cose and lipid metabolism. The metabolic properties

of acute and chronic exercise should therefore

be advantageously used in the treatment of obesity.

(See Anorexia Nervosa; Bulimia Nervosa; Obesity:

Etiology and Diagnosis; Fat Distribution; Treatment.)

See also: Anorexia Nervosa; Bulimia Nervosa;

Carbohydrates: Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism;

Requirements and Dietary Importance; Energy: Energy

Expenditure and Energy Balance; Fats: Digestion,

Absorption, and Transport; Requirements; Hormones:

Thyroid Hormones; Hypertension: Physiology;

Hypertension and Diet; Obesity: Etiology and Diagnosis;

Fat Distribution; Treatment; Protein: Requirements;

Water: Physiology

Further Reading

Atkinson RL (1989) Low and very low calorie diets.

Medical Clinics of North America 73: 203–215.

Atkinson RL and Hubbard VS (1994) Report on the NIH

workshop on pharmacologic treatment of obesity.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 60: 153–156.

Black D, James WPI and Besser GM (1983) Obesity. Jour-

nal of the Royal College of Physicians of London 17:

5–65.

Bray GA and Gray DS (1988) Treatment of obesity: an

overview. Diabetes and Metabolic Review 4: 653–679.

Cowley DK and Sizer FS (1987) Fad diets, fact and fiction?

Nutrition Clinics 2.

Flier JS and Foster DW (1999) Eating disorders: obesity,

anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. In: Wilson JD,

Foster DW, Kronenberg HM and Larsen PR (eds)

SLIMMING/Metabolic Consequences of Slimming Diets and Weight Maintenance 5295

Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 9th edn., pp.

1061–1097. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Howard AN, Bray GA, Novin D and Bjorntorp P (eds)

(1981) Proceedings of a symposium on obesity and

hypertension. International Journal of Obesity

5(suppl 1).

Garrow JS (1978) Energy Balance and Obesity in Man.

Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Olson RE (ed.) (1986) Diet and behavior: a multidisciplin-

ary evaluation. Nutrition Reviews 44.

Wurtman RJ and Wurtman JJ (eds) (1987) Human obesity.

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 499.

SMOKED FOODS

Contents

Principles

Production

Applications of Smoking

Principles

L Woods, Woodside Consulting, Camberley, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 The foods most commonly smoked are meats, fish,

shellfish, and cheese, although some snack foods and

nuts are smoke-flavored. Meats or fish grilled over an

open fire are exposed to smoke during cooking, but

are not normally considered to be smoked foods as

such. In general, smoke is produced by substantially

raising the temperature of wood, and limiting the air

supply so as to prevent combustion but allow destruc-

tive distillation.

0002 Smoke flavors and essences may be prepared by

condensation of smoke obtained by pyrolysis of

wood in a limited supply of air, when the product is

known as pyroligneous acid. The initial condensate

separates into an aqueous phase and a tarry phase.

The smoke condensate may be separated into frac-

tions by physical separation techniques or by solvent

extraction. These fractions may be further purified to

remove hazardous substances known to be present in

smoke. Smoke flavorings include smoke condensates,

fractions thereof, and mixtures of such fractions.

0003 The temperature at the center of a heap of smolder-

ing sawdust may be 700–1000

C, but the tempera-

ture gradient is steep, with the temperature falling to

300

C or less a short distance from the center. Above

approximately 200

C, the wood undergoes destruc-

tive distillation, and the desired decomposition prod-

ucts are best generated in the 200–400

C range. This

smoke is allowed to diffuse over, or more commonly

is blown over the food to be smoked, with varying

levels of control depending on the technology avail-

able.

0004The thermal decomposition of wood can be influ-

enced by numerous factors such as temperature,

wood composition, amount of oxygen present, and

amount of water vapor available during pyrolysis.

Temperature is the most important and the various

constituents of wood react at different temperatures.

The first major component to undergo thermal

decomposition is hemicellulose, which decomposes

between 200 and 260

C to yield furan and its deriva-

tives, as well as a series of aliphatic carboxylic acids.

Cellulose is the next major wood component to

undergo thermal decomposition, pyrolysis occurring

between 260 and 310

C, which in turn leads to the

formation of carbonyls, acetic acid, and its deriva-

tives, together with water and occasionally small

amounts of furans and phenols.

0005The lignin fraction is the most resistant, thermal

decomposition occurring at 310–500

C, and the de-

rived compounds include phenols and phenolic esters

along with their homologs and derivatives. Thus, if a

relatively low temperature is used, lignin may not be

completely degraded, and the resulting smoke will

have a different chemical composition from smoke

produced at a higher temperature. (See Cellulose;

Hemicelluloses; Lignin.)

0006When first formed, smoke is generated as a vapor,

but as it cools, some less volatile components con-

dense to form a disperse liquid phase, which, along

with soot particles, if present, constitute visible

smoke. The remaining more volatile components dis-

tribute between the gaseous and disperse phases

according to their solubility and volatility at the

5296 SMOKED FOODS/Principles