Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

disorder. The formal criteria as defined by the Ameri-

can Psychiatric Association in 1994 are listed below:

1.

0002 Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a

minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g.,

weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight

less than 85% of that expected; or failure to make

expected weight gain during period of growth,

leading to body weight less than 85% of

expected).

2.

0003 Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat,

even though underweight.

3.

0004 Disturbance in the way in which one’s body

weight or shape is experienced, undue influence

of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or

denial of the seriousness of the current low body

weight.

4.

0005 In postmenarcheal females, amenorrhea, i.e., the

absence of at least three consecutive menstrual

cycles. (A woman is considered to have amenor-

rhea if her periods occur only following hormone,

e.g., estrogen, administration.)

Subtypes

1.0006 Restricting type: during the current episode of

AN, the person has not regularly engaged in

binge-eating or purging behavior (i.e., self-induced

vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or

enemas).

2.

0007 Binge-eating/purging type: during the current epi-

sode of AN, the person has regularly engaged in

binge-eating or purging behavior (i.e., self-induced

vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or

enemas).

Prevalence

0008 AN is, in about 90% of cases, a disorder of females,

typically between the ages of 12 and 40. Studies of the

age of onset of this disorder reveal bimodal peaks at

14 and 18 years of age; at these ages, the demands of

secondary sexual development and autonomy in the

context of leaving home may be related to the

increased incidence. The current accepted prevalence

rate for AN among western adolescent and young

adult women is approximately 0.5–1.0%. AN is,

relatively speaking, a culture-bound disorder limited

to industrialized societies with western values.

Etiology and Groups at Risk

0009 The etiology of this disorder is unknown; most clin-

icians and researchers endorse a multidimensional

model of AN which acknowledges psychological, bio-

logical, and social risk factors that exist at the level of

the individual, the family, and society. While dieting is

almost ubiquitous behavior among women in western

society, the significant medical and psychiatric mani-

festations of AN and its characteristic psychological

features argue for the definition of AN as a distinct

disorder, and not a simple exaggeration of current

western values; indeed, AN was recognized long

before our cultural preoccupation with being thin.

0010At the level of the individual, women who by career

choice experience pressures both to be thin and to

achieve may be particularly vulnerable. This includes

ballerinas, fashion models, and gymnasts, in whom

thinness and perfectionism are not only demanded

but also equated. Conflicting pressures on women to

nurture and to perform professionally may intensify

concerns about control that are shifted on to weight

regulation as a focus. Further, chronic physical illness,

physical or sexual abuse, or other traumas which

heighten preoccupation with the body as a reflection

of control or self-esteem may increase vulnerability

to AN.

0011At the familial level, there may be a magnification

of social idealization of thinness and denigration of

obesity. Genetic influences through vulnerability to a

variety of psychiatric disorders such as depression,

alcoholism, and eating disorders themselves in other

family members may also play a role. First-degree

relatives of AN subjects also display an elevated

prevalence of eating disorders over controls. Twin

studies indicate an increased concordance rate for

monozygotic (identical) versus dizygotic (nonidenti-

cal) twins.

0012At the societal level, the last 75 years have wit-

nessed shifting models of the ideal female form

toward thinness, in contrast to the increasing bio-

logically ideal weights for women in the context of

good nutrition. However, it must be remembered that

the decription of AN in 1874 long predates our

cultural preoccupation with thinness and a broader

understanding of this disorder must be sought.

Psychopathology

0013The focal behavioral point of AN is the individual’s

relentless pursuit of thinness and the associated con-

viction that her body is too large. This latter belief

may emanate from a variety of sources, from a past

history of obesity (with its attendant social humili-

ation and a sense of failure) to physical or sexual

abuse which has led to body loathing. Alternatively,

AN may reflect a symbolic focus on the body in a

search for personal mastery that in turn reflects a

sense of personal ineffectiveness. It may also allow

retreat from the maturational demands of adoles-

cence, as expressed by the development of secondary

244 ANOREXIA NERVOSA

sexual characteristics. Associated psychopathological

features often include a fear of losing control in many

spheres, self-esteem that is highly contingent on the

opinions of others, an all-or-nothing thinking style

that allows no middle ground between being thin

and being fat, and a pervasive sense of helplessness.

Clinical Features

0014 The initial manifestations of AN are deceptively

benign; the disorder frequently commences with

dieting behavior which is itself common in the west-

ern female population. However, this particular form

of dieting leads to increased criticism of one’s appear-

ance and greater social isolation than typical adoles-

cent dieting behavior; further, weight goals continue

to drift downward as they are approached. Food

aversion becomes more general than specific and,

as emaciation progresses, the individual exhibits a

marked denial of her illness. A typical but not univer-

sal characteristic of AN is a distortion of body image

in which the individual overestimates her body size

substantially, believing herself to be fat even when

thin. This perceptual disturbance is usually accom-

panied by feelings of loathing of one’s appearance.

0015 At the level of behavior, routine dieting evolves into

more elaborate food avoidance and other activities to

counteract the effect of ingested calories. Individuals

restrict their intake dramatically, skip meals, or

secretly dispose of food. Elaborate rituals related to

eating develop, and decreased consumption of food is

paralleled by increasing cognitive preoccupation with

it. This translates into thinking, reading, and dream-

ing about food or working in food-related industries.

Weighing oneself becomes not only a frequent ritual

but also a regulator of subsequent eating, socializa-

tion, and self-esteem. In addition to calorie restric-

tion, individuals may exercise intensively for the

express purpose of weight loss, or use purgative tech-

niques such as diuretics, diet pills, laxatives, or self-

induced vomiting.

0016 Initially, because the consequences of the disorder

are consistent with the individual’s desire to be thin

and in control, there is seldom the motivation to seek

help or to acknowledge the evolving AN as a prob-

lem. Rather, the individual with AN may contact a

nutritionist, physician, or other health professional,

seeking advice on dieting in the absence of obesity or

help in dealing with the secondary medical and

psychiatric effects of starvation.

Physiological Effects

0017 Virtually no body system is spared the effects of

nutritional deprivation in AN. The changes are too

extensive to enumerate here; they reflect not only loss

but also homeostatic compensatory mechanisms to

minimize energy expenditure in the context of de-

creased energy intake. Loss of menstrual function is

the most classically recognized of these sequelae, to

the point that it is a diagnostic criterion thought to

reflect disturbances in gonadotropin function in the

hypothalamus. Other common starvation effects

include lowered body temperature and heart rate,

dry skin and the development of a fine body hair,

abdominal bloating and constipation, and edema.

Psychological Effects

0018Starvation due to AN also produces distinct psycho-

logical effects such as depressed, irritable, or anxious

mood, cognitive preoccupation with food, and de-

creased concentration. Individuals with AN may

appear to suffer from a coexistent depressive illness

and are vulnerable to the long-term development of

such disorders. However, many of the psychological

sequelae of the disorder – which are more troubling to

the affected individual than the dieting itself – are

reversible with adequate nutrition.

Nutritional Status

0019The food restriction of AN may be severe. Individuals

may abstain from all solid foods for days at a time or

subsist on as little as 200–500 calories per day. Typic-

ally, there is an avoidance of perceived high-calorie,

high-fat foods – and foods become imbued with

moral as well as nutritional value. Individuals may

develop frank cachexia, with vigorous dieting and

exercise behaviors persisting at weights as low as

30 kg. Fasting hypoglycemia, abnormal glucose toler-

ance tests, and increased insulin sensitivity are among

the metabolic responses to this form of starvation.

Elevations of cholesterol and carotene may occur

and plasma zinc levels have variably been reported

as low. Low platelet, red blood cell and white blood

cell counts, accompanied by a relative paucity of

precursors in bone marrow, have been described as a

consequence of the disorder.

0020The nutritional status of AN patients may have

implications for the chronicity of the disorder. Brain

neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepineph-

rine (noradrenaline) are integral in the hypothalamic

regulation of appetitive behavior. Serotonin synthesis

itself is dependent on the dietary availability of its

precursor, the essential amino acid tryptophan. Tryp-

tophan availability may be decreased in AN, and

both neuroendocrine provocation tests and cerebro-

spinal fluid metabolite assays indicate altered sero-

tonin activity in AN. This may be associated with

ANOREXIA NERVOSA 245

disturbances in satiety, thought (with increased obses-

sionality and perfectionism), mood, and sleep found

in AN. Delayed gastric emptying may occur in re-

sponse to the decreased volume of food consumed.

This further contributes to altered senses of satiety; an

augmented sense of fullness may perpetuate food re-

striction.

Diagnosis

0021 The diagnostic criteria of the American Psychiatric

Association listed above reflect the confluence of bio-

logical, behavioral, and psychological factors charac-

teristic of AN. However, clinicians may perceive them

as arbitrary, particularly with regard to the degree of

weight loss required and the presence of amenorrhea

as essential for diagnosis. Epidemiological research

requires dichotomous criteria, while clinical practice

demands the recognition from a dimensional perspec-

tive of disorders in evolution. The diagnosis of AN in

a young woman with weight loss requires consider-

ation of other medical and psychiatric illnesses with

a superficially similar presentation. These include

endocrine disorders, bowel disease, malignancy, de-

pression, schizophrenia, and conversion disorder. All

of these differential diagnoses typically lack the

central psychological preoccupation of AN – the

relentless pursuit of thinness.

Treatment

0022 The goal of treatment of AN includes but is not

limited to nutritional rehabilitation. Clearly, if weight

gain is the only purpose of therapy for an individual

dedicated to the attainment of weight loss, her com-

mitment to the treatment will be poor. At the same

time, however, treating personnel cannot ignore the

nutritional status of the individual while focusing on

psychological issues; when this occurs, it results in

collusion with the denial by the individual of her

illness and obscures the connection between food

deprivation and its sequelae.

0023 The initial phase of treatment is a careful diagnos-

tic assessment, with emphasis on both the evolution

of the disorder and its various sequelae. A family

assessment is often relevant, particularly in younger

patients, both to understand familial influences and

to substitute education for guilt. A target weight

range is established, allowing the minor fluctuations

that are normal (1–2 kg). This range should be able to

be maintained without dieting, should allow the

return of normal menstrual function, and should

reflect consideration of the individual’s longitudinal

weight history. Generally, a target weight range is

above 90% of the average for an individual’s weight

and height or a body mass index (kg m

2

) greater

than 20. Despite a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge

of nutrition, these individuals usually require direct-

ive counseling regarding meal frequency, portion size,

and macronutrient selection. A daily diary of eating

and associated thoughts, feelings, and behaviors may

be helpful. An initial intake of 1500 calories per day is

usually sufficient to promote weight gain without

inducing the gastric dilatation that can complicate

refeeding. A rate gain of 0.5–1.0 kg per week is desir-

able; more rapid weight gain may induce its own

complications, including hypophosphatemia and

edema, as well as mistrust in an individual who is

reluctantly relinquishing weight control. Caloric

intake is usually increased by 200–300 calories per

week toward a goal of 2400–3000 calories per day.

To date, controlled clinical trials indicate no role for

drugs in the promotion of eating or weight gain in

AN; food remains the drug of choice; there is modest

evidence that the antidepressant fluoxetine may assist

weight-recovered AN patients to maintain weight

gain, possibly through an antiobsessional effect.

0024Psychotherapy is usually offered in conjunction

with nutritional rehabilitation, and builds on the

establishment of a therapeutic relationship. Issues

include the recognition of feelings, self-trust, and dis-

connecting one’s sense of self-worth from body

weight. A variety of approaches, from psychodynamic

to cognitive-behavioral, may be employed. Family

therapy may be particularly helpful for the younger

AN patient.

0025Hospitalization is not necessary for the majority of

individuals with AN; rather, it is reserved for cases

where the weight loss has been either precipitously

acute or impinging on basic function, where medical

sequelae such as hypokalemia pose an imminent risk,

where suicidal tendencies accompany the AN, where

AN coexists in a threatening fashion with another

illness such as diabetes mellitus, or where other

forms of treatment have been ineffective.

Prognosis

0026AN is a usually gradual, initially covert, and some-

times chronic disorder. Long-term follow-up studies

indicate that while two-thirds of patients show even-

tual improvement or recovery, less than one-third

recover within 3 years. More disturbing, some long-

term follow-up studies have indicated a mortality rate

of 10–20% as a consequence of AN. In addition,

these women are vulnerable over the long term to

the development of mood disorders, anxiety dis-

orders, and substance abuse, regardless of whether

the AN is active or quiescent. They are also sus-

ceptible to such diverse medical complications as

246 ANOREXIA NERVOSA

osteoporosis with pathological bone fractures and a

form of brain tissue atrophy. Beyond reversal of the

nutritional deprivation and weight loss, there is no

established method of tertiary prevention.

See also: Adolescents; Bulimia Nervosa; Famine,

Starvation, and Fasting; Premenstrual Syndrome:

Nutritional Aspects; Slimming: Slimming Diets;

Metabolic Conseqences of Slimming Diets and Weight

Maintenance

Further Reading

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Wash-

ington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Practice guideline

for the treatment of patients with eating disorders.Amer-

ican Journal of Psychiatry 157 (suppl): 1–39.

Garfinkel P, Lin E, Goering P et al. (1996) Should amenor-

rhea be required for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa?

Evidence from a Canadian community sample. British

Journal of Psychiatry 168: 500–506.

Garner DM and Garfinkel PE (eds) (1997) Handbook of

Treatment for Eating Disorders, 2nd edn. New York:

Guilford Press.

Goldbloom D (1997) Evaluating the efficacy of pharmaco-

logic agents in the treatment of eating disorders. Essen-

tial Psychopharmacology 2: 71–88.

Goldbloom D and Kennedy S (1995) The medical compli-

cations of anorexia nervosa. In Brownell KD and Fair-

burn CG (eds) Eating Disorders and Obesity: A

Comprehensive Handbook, pp. 266–270. New York:

Guilford Press.

Kaplan AS and Garfinkel PE (eds.) (1993) Medical Issues

and the Eating Disorders: The Interface. New York:

Brunner/Mazel.

Katzman D, Lambe E, Ridgley J, Goldbloom D, Mikulis D

and Zipursky R (1996) Cerebral gray matter and

white matter volume deficits in adolescent females

with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Pediatrics 129:

794–803.

Kaye WH, Gwirtsman H, Obarzanek E and George DT

(1988) Relative importance of calorie intake needed to

gain weight and level of physical activity in anorexia

nervosa. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 47:

989–994.

Kennedy S and Goldbloom D (1994) Advances in the treat-

ment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. CNS

Drugs 1: 201–212.

Szmukler G, Dare C and Treasure J (eds) (1995) Handbook

of Eating Disorders. Chichester: John Wiley.

Anthropometry See Nutritional Assessment: Anthropometry and Clinical Examination

ANTIBIOTIC-RESISTANT BACTERIA

J J Klawe and M Tafil-Klawe, The Ludwik-Rydygier

Medical University, Bydgoszcz, Poland

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Bacterial Resistance to Antimicrobial

Agents

0001 The antimicrobial resistance may be intrinsic or ac-

quired. Intrinsic–innate resistance may be considered

a fundamental property of the organism: it was pre-

sent in bacterial strains isolated before the antibiotic

era. Some organisms can produce enzymes that chem-

ically modify a specific drug. Bacteria may also use

the system to transport detrimental compounds out of

a cell, using efflux pumps.

0002 Acquired resistance is not found in species strains,

unless they have been exposed to antimicrobial drugs.

Acquired resistance may occur as a result of spontan-

eous chromosomal mutation or by acquisition of

extrachromosomal elements, such as plasmids and

transposons.

0003Chromosomal mutation can occur during treat-

ment or in the absence of the agent, against which

resistance develops. Extrachromosomal pieces of

DNA, called plasmids (R plasmids), contribute to

bacterial virulence or to antimicrobial resistance.

Genes of resistance to antimicrobial agents may be

transferred from chromosomes to plasmids or from

plasmids to chromosomes, as a result of classic re-

combination. The plasmid and chromosome re-

combine pieces of DNA in areas of genetic

homology. The presence of a rec A gene is needed.

Many plasmids are composed of two parts: the resist-

ance genes, or R genes, which code for the resistance

traits, and the resistance transfer factor, which codes

ANTIBIOTIC-RESISTANT BACTERIA 247

for the transfer of the plasmid to other bacteria by

conjugation.

0004 Transposons, however, can insert into chromo-

somes in areas where no homology exists, inde-

pendent of a rec A gene. Thus, transposons are less

restrictive and play a major role in the transfer of

resistance among many different species.

Biochemical Mechanisms of Bacterial

Resistance

0005 The biological mechanisms of bacterial resistance

may be classified into four groups:

1.

0006 modification of the target site of the antimicrobial

agent – for example, resistance to rifampin caused

by alteration of the targeted RNA polymerase;

2.

0007 enzymatic inactivation of the agent – production

of b -lactamases, enzymes that hydrolyze the b-

lactam ring of the b-lactam antibiotics;

3.

0008 decreased membrane permeability and entry of the

agent – resistance to tetracycline is due to de-

creased accumulation of the antimicrobial agent;

4.

0009 a combination of two or more mechanisms – for

example, resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Examples of Emerging Antimicrobial

Resistance

Enterococci

0010 The Enterococci are a group of bacteria that are a

part of the normal intestinal flora. Many enterococci

have plasmid-encoded resistance genes. This group of

bacteria is intrinsically less susceptible to many

common antimicrobials. Enterococci cause nosoco-

mial infections, an old problem that has occurred

ever since the first hospitals were established. Now-

adays, nosocomial infections make up at least half of

all cases of infectious disease treated in the hospitals

and may range from very mild to fatal. Enterococci

are a common cause of nosocomial urinary-tract in-

fections as well as wound and blood infections.

Staphylococcus aureus

0011 Many people, including healthcare personnel, are

carriers of this organism. It is a common cause of

nosocomial pneumonia and surgical infections. Hos-

pital strains are resistant to a variety of antibiotics.

Over the past 50 years, most strains have acquired

resistance to penicillin, due to the acquisition of a

gene encoding the enzyme penicillinase. New strains,

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, are

resistant to methicillin and to other b-lactam drugs.

Staphylococcus aureus has also been reported to have

become vancomycin-resistant.

Staphylococcus

Species other than

S. aureus

0012These normal skin flora can colonize the tips of intra-

venous catheters. The resulting biofilms continuously

seed organisms into the bloodstream, thus increasing

the risk of systemic infection.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

0013Some strains, now isolated, are resistant to penicillin.

This acquired resistance is due to the modifications in

the chromosomal genes coding for different penicil-

lin-binding proteins, which decrease their affinities

for the drug. The nucleotide changes are due to the

acquisition of chromosomal DNA from other species

of Streptococcus.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

0014Treatment of infections of Mycobacterium tubercu-

losis has always been a complicated process, often

requiring a combination of two or three different

drugs taken for 6 months or more. Mycobacterium

tuberculosis is developing resistance to first-line

drugs. Strains that are resistant to isoniazid and

rifampin are called multiple drug-resistant Mycobac-

terium tuberculosis.

Pseudomonas

species

0015These bacteria grow in a large number of moist,

nutrient-poor environments, such as the water in the

humidifier of a mechanical ventilator. Pseudomonas

species are resistant to many antimicrobial drugs.

They are a common cause of hospital-acquired pneu-

monia and infections of the urinary tract and burn

wounds.

Slowing down the Emergence and Spread

of Antimicrobial Resistance

0016More effort from healthcare workers to identify the

causative agent of infectious diseases and to prescribe

suitable antimicrobials is necessary to slow down the

spread of antimicrobial resistance. Also, patients need

to be vigilant, and a great effort must be made to

educate the public about the appropriateness and

limitations of antibiotics.

See also: Mycobacteria; Staphylococcus: Properties

and Occurrence; Detection; Food Poisoning

Further Reading

Advisory Committee on Microbiological Safety of Foods

(UK) (1999) Report on Microbial Antibiotic Resistance

in Relation to Food Safety. London: The Stationery

Office.

248 ANTIBIOTIC-RESISTANT BACTERIA

Howard BJ (1994) Clinical and Pathogenic Microbiology.

London: Mosby.

Jacoby GA and Archer GL (1991) New mechanisms of

bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents. New Eng-

land Journal of Medicine 324: 601–612.

McDougal LK and Thornsberry C (1986) Role of beta-

lactamase in staphylococcal resistance to penicillinase-

resistant penicillins and cephalosporins. Journal of Clin-

ical Microbiology 23: 832–839.

Nester EW, Anderson DG, Roberts CE, Jr., Pearsall NN and

Nester MT (2001) Microbiology – A Human Perspec-

tive. London: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Patterson JE and Zervos MJ (1990) High-level gentamicin

resistance in enterococcus: Microbiology, genetic basis

and epidemiology. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 12:

644–652.

ANTIBIOTICS AND DRUGS

Contents

Uses in Food Production

Residue Determination

Uses in Food Production

K N Woodward, Veterinary Medicines Directorate,

Weybridge, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Background

0001 Veterinary medicines are used to improve or maintain

the health of animal species regardless of whether

these are intended for food production. They are

designed and manufactured to cover a wide variety

of prophylactic and therapeutic purposes, and they

are administered to household pets, exotic species,

and wild animals in addition to food-producing

animals.

0002 Most countries possess a governmental regulatory

authority charged with assessing veterinary medicines

and granting some form of marketing authorization

before a product may be sold, and the UK’s system is

used here to exemplify this in practice. Veterinary

medicines, like their human counterparts, are asses-

sed against three basic criteria – efficacy, quality, and

safety – although the terms of these criteria differ

from country to country. The efficacy is the ability

of the drug to accomplish the task claimed for it by its

producer. Quality refers to pharmaceutical quality;

the levels of contaminants must meet acceptable cri-

teria, the shelf-life must be as claimed by the manu-

facturer, and the product must be produced to

appropriate standards. Safety means that the product

must not harm the animal patient, the environment,

the users of veterinary medicines, or the consumer of

food of animal origin. This latter aspect is of para-

mount importance when assessing the safety of veter-

inary medicines. When a veterinary drug is given to

an animal, most of the dose will be excreted in urine,

feces, and expired air, but small amounts will remain

in body tissues. These are known as residues, and it is

the responsibility of regulatory authorities to ensure

that these do not pose a threat to the consumer when

veterinary medicines are used in food-producing

animals.

Uses of Veterinary Medicines

0003In general, veterinary medicines are available to treat

most of the types of animal disease state that are

encountered in humans. In practice, diseases such as

cancer are not usually treated in food-producing

species, largely for economic reasons, although they

are frequently dealt with in companion animal

medicine. The majority (but not by any means all)

of the medicines used in food-producing animals are

for the prevention or treatment of diseases caused by

infectious agents. These fall into a number of categor-

ies, and they are described briefly below.

Antibiotic and Antimicrobial Agents

0004Antibiotics are antibacterial agents derived from

living organisms, but the term includes closely related

synthetic analogs. The archetypal compound is peni-

cillin, the structure of which has now formed the basis

for a wide range of naturally occurring and semisyn-

thetic analogs. Other major categories of antibiotics

ANTIBIOTICS AND DRUGS/Uses in Food Production 249

used in veterinary medicine are the tetracyclines, the

aminoglycosides, the macrolides, and the polymixins.

Sulfonamides constitute the major class of antimicro-

bial agent, drugs that are unrelated to naturally

occurring compounds. A number of sulfonamides

have been prepared for fast, medium, or long-acting

functions. Sulfadimidine is one of the most widely

used sulfonamide drugs in veterinary medicines, par-

ticularly in pig production, where it is employed to

combat respiratory disease.

Ectoparasiticides

0005 Cattle and sheep are often subject to attack by ecto-

parasites. For example, in the UK and other parts of

Europe (and indeed elsewhere) cattle are susceptible

to attack by the warble fly (Hypoderma spp.), which,

in addition to causing animal suffering, results in

considerable economic loss. Sheep scab is another

disease that poses serious animal welfare and eco-

nomic problems, and in several countries, including

the USA and the UK, it is a notifiable disease. Both

diseases are treated and prevented by the application

of organophosphorus compounds. For warble fly,

treatment is usually in the form of a relatively viscous

formulation that is spread on to the back of the

animal (a pour-on formulation); in the case of sheep

scab, dipping and showering are the most therapeut-

ically and economically effective methods currently

available.

0006 Fish too are susceptible to external parasites, and

as fish farming (aquaculture) becomes more import-

ant, so the effects of disease become more significant.

Salmon farming is a fast-growing industry in many

parts of the world, particularly in North America,

Chile, Norway, and Scotland. Salmon are vulnerable

to infestation by the sea louse, an arthropod that

attacks the external surface of the fish and in severe

cases causes death.

Anthelmintics

0007 ‘Anthelmintics’ is a term almost universally abused to

describe agents used to treat internal parasite infest-

ations and not merely those caused by helminth

worms. Many of the diseases caused by internal para-

sites can be extremely distressing to affected animals,

and all can result in substantial economic losses. A

number of drugs have been developed to combat

these diseases, including the benzimidazoles, levami-

sole and invermectin.

0008 The first benzimidazole to achieve widespread use

in veterinary medicine was thiabendazole, but newer

compounds include albendazole, oxfendazole, fen-

bendazole, and mebendazole. Levamisole is extreme-

ly efficacious in the treatment of gastrointestinal

nematodes in cattle, sheep, and pigs. Ivermectin is a

mixture of two closely related compounds derived

from abamectin, a metabolite of Streptomyces aver-

mitilis, and it has found wide use as an antiparasitic

agent in veterinary medicine (and in some areas of

human medicine).

Antifungal Agents

0009In veterinary medicine, several drugs have found uses

as antifungal agents for application to the external

surfaces of the body. These include ketoconazole,

thiabendazole, aliphatic acids, and benzoic acid.

Nystatin and griseofulvin are extensively used as

systemic treatments for fungal infections in both

food-producing and other species.

Steroid Hormones

0010It has long been known that testosterone exerts ana-

bolic effects in both humans and animals, and testos-

terone and chemically related steroid hormones

have been widely used for this purpose in beef

production. However, the EC has prohibited the

growth-promoting uses of steroid hormones in

animal production, although certain so-called zoo-

technical (e.g., synchronization of estrous for mating)

and therapeutic (e.g., treatment of recurrent abor-

tion) uses are still permitted using naturally occurring

compounds or closely related derivatives. In other

countries, notably in the North and South Americas,

the growth-promoting uses of steroid hormones are

legally permitted.

Regulatory Control of Veterinary

Medicines

0011Regulatory control of the uses of veterinary medicines

is almost universal, and, as described earlier, drugs

must meet exacting standards of efficacy, quality, and

safety. In the UK, for example, human and veterinary

medicines are controlled by the Medicines Act 1968

and by integrated EC legislation. Product licences and

other forms of marketing authorization are granted

by a licensing authority established under the act. The

Licensing Authority is defined in the act as the Health

and Agriculture Ministers acting together, and in

practice, responsibility is given over to civil servants

working in the Department of Health for human

medicines, and in the Veterinary Medicines Director-

ate (VMD) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries

and Food (MAFF) for veterinary medicines. Applica-

tions for product licences are submitted to the VMD

by companies together with the quality, efficacy, and

safety data. Staff of the VMD then vigorously assess

these data and submit them with their appraisals to

250 ANTIBIOTICS AND DRUGS/Uses in Food Production

the independent Veterinary Products Committee ap-

pointed under the Medicines Act. This committee

may then recommend licensing, require further infor-

mation, or refuse the application. When a product is

not recommended for licensing, companies have

recourse to an appeals procedure, whereby they can

submit their arguments. (See Legislation: Contamin-

ants and Adulterants.)

0012 Essentially similar systems exist in other countries,

including other member states of the EC. For this

latter group, national laws are amended from time

to time to incorporate EC legislation. Three European

directives are worthy of note for the impact that these

have had on national legislation within the EEC.

0013 The two Veterinary Medicines Directives (81/

851/EEC and 81/852/EEC) provide a legislative

framework for the European ‘licensing’ of conven-

tional veterinary medicines. They establish an expert

committee, the Committee for Veterinary Medicines

Products, and offer a system of control, including a

multistate authorization procedure within the EC.

Moreover, they provide comprehensive guidelines on

safety, quality and efficacy. The so-called Feed Addi-

tives Directive (70/524/EEC) covers both medicinal

and nonmedicinal ingredients intended to be added to

the animal feeds. Although conventional veterinary

medicines and medicinal feed additives are therefore

dealt with separately at community level, in the

UK, they are subject to the same treatment under

the Medicines Act, once they have been accepted

by the EC.

0014 On a worldwide basis, the marketing authorization

of veterinary medicines and the steps preceding this

can be summarized briefly as follows: development of

a drug and its formulations; testing to fulfill the

requirements of safety, quality and efficacy; submis-

sion of an application for marketing authorization

with the data from safety, quality, and efficacy tests

to the appropriate national authorities; appraisal, as-

sessment, and consideration by those authorities;

granting or refusal (or requirement for further stud-

ies) of marketing authorization.

Safety Data Requirements

0015 Safety data with respect to consumer safety can be

divided into two main categories: toxicity data and

residues data. In recent years, there has been an in-

creasing demand for data on microbiological safety

with respect to possible effects on the gastrointestinal

flora of consumers.

Toxicology Studies

0016 Toxicology data usually take the form of the results

from a package of studies using laboratory species

and in-vitro tests. Pharmacokinetic and pharmaco-

dynamic data are also used where relevant in the

interpretation of the results of these endeavors. The

precise requirements for toxicology testing differ

from country to country, but in general terms, they

are exemplified by those of the EC, which include the

following:

.

0017single-dose (acute) toxicity;

.

0018repeated-dose toxicity;

.

0019reproductive toxicity: effects on reproduction;

effects on the embryo or fetus and teratogenicity

(birth defects);

.

0020mutagenicity studies;

.

0021carcinogenicity (induction of tumors) studies;

.

0022pharmacodynamics.

.

0023pharmacokinetics;

.

0024observations in humans.

0025There are three basic aims in conducting toxicology

studies: to identify a no-observed effect level (NOEL),

to calculate an acceptable daily intake (ADI), and to

determine a maximum residues limit (MRL).

0026The NOEL is the lowest dose level, usually quoted

in milligrams per kilogram bodyweight, below which

an effect or range of effects do not occur in the species

being investigated (usually mice or rats). It is usually

necessary to eliminate those effects thought to be

irrelevant – usually because they are known to occur

only in rodents or because they represent a phenom-

enon induced by excessive doses – and then select the

study thought to be of most relevance, although in

practice, the lowest NOEL from the battery of tests is

often used.

0027The ADI is calculated by dividing the NOEL by an

arbitrary safety factor. This is usually 100 for minor

toxic effects, but factors of up to 2000 may be used

with severe effects or when the battery of tests is

considered to be deficient in some relatively minor

aspect; if deficient in some major area, e.g., if a car-

cinogenicity study has not been conducted, an ADI

may not be set. The ADI is often expressed in terms of

human weight by use of the additional factor of

65 kg, this being widely accepted as representing

human adult weight. Hence, the ADI can be

expressed (in milligrams per day) as follows:

ADI ¼ðNOEL 65Þ= safety factor:

The MRL is the maximum permitted level of the drug

residue, which regulatory authorities perceive as

being acceptable in food of animal origin on the

basis of the results of the safety studies described

earlier. As such, it is often difficult to describe in

purely arithmetical terms, for, although it is based

primarily on the ADI, it must take into account

other factors, not least of which is the intake of the

ANTIBIOTICS AND DRUGS/Uses in Food Production 251

food commodity in question. Every consumer has a

varied intake of most of the products of food of

animal origin, such as muscle, fat, kidney, and liver;

some, for example, eat more liver or kidney than

others. To try to cover the majority of possibilities,

the Food and Agriculture Organization, World

Health Organization (FAO/WHO) Joint Expert

Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) has recom-

mended standard daily intake values of 300 g of

muscle, 100 g of liver, 50 g of fat, 50 g of kidney,

100 g of egg, and 1.51 of milk to be used in the

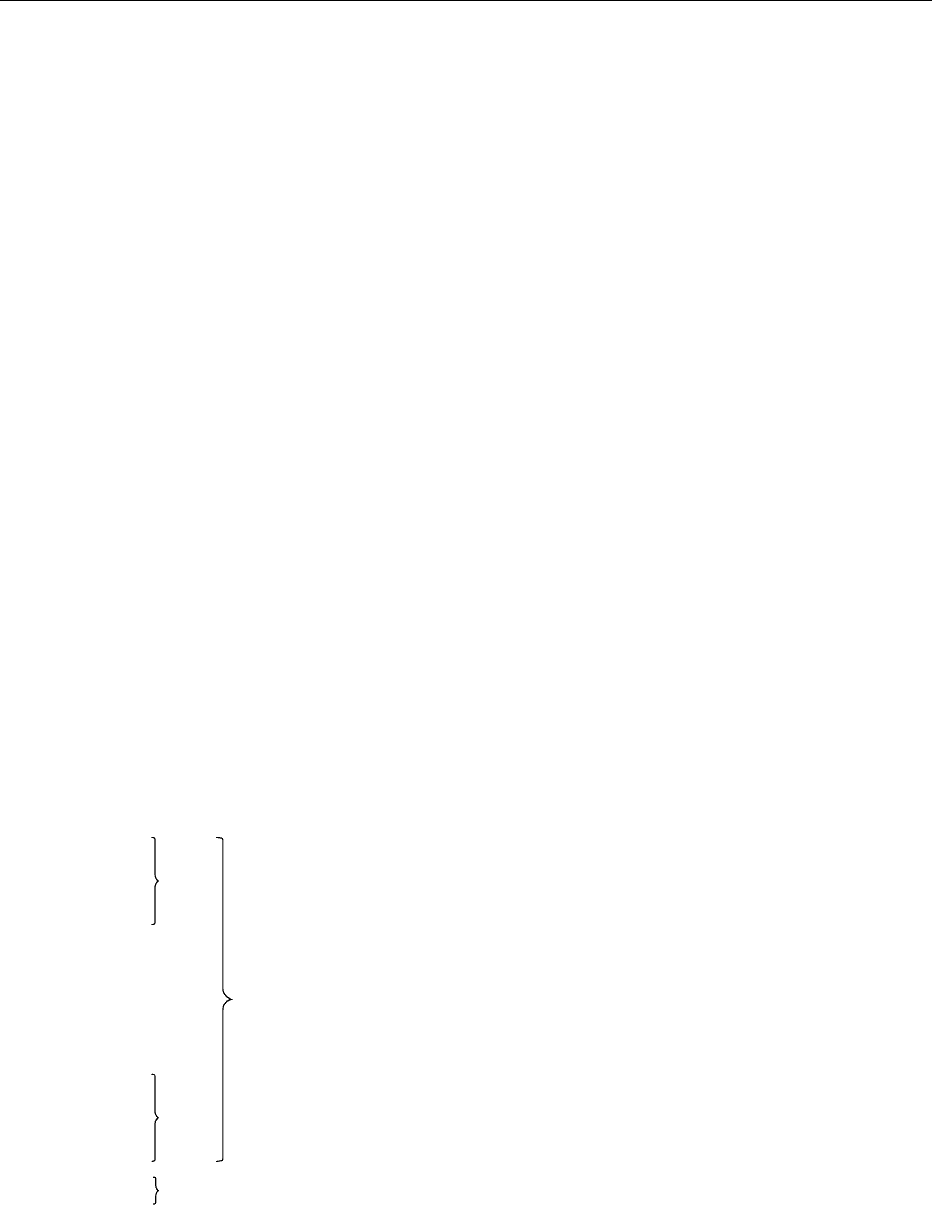

elaboration of MRLs. The types of food-producing

animals are shown in Figure 1. In general terms, the

ADI is ‘spread’ across the different types of food

commodity, bearing in mind their relative standard

intakes, so that MRLs, which will not result in the

ADI being exceeded, can be elaborated.

0028 When considering values for MRLs, a major factor

that must be taken into account is the chemical nature

of the residues and their resultant biological activity.

This is an extremely complex area and one that is not

without controversy. Most chemicals, including vet-

erinary medicines, when given to animals are con-

verted to a range of metabolites, usually but not

exclusively by the liver. Consequently, the residues

present in tissue may be the parent compound or a

mixture of metabolites or both. Moreover, either the

parent drug or its metabolites may be highly reactive

and may therefore combine with cellular constituents

to give rise to so-called bound residues. In these cir-

cumstances, it is desirable and sometimes essential to

know to what extent these may be released to yield

potentially harmful substances following consump-

tion of products of animal origin. The most likely

place for such a release to occur is in the gastrointest-

inal tract of the consumer, and a number of animal as

well as several chemical models have been developed

in an attempt to provide information on this area of

hazard assessment. One of these makes use of a tech-

nique known as relay toxicology, although in this

context, relay pharmacology might be more appro-

priate. The radiolabeled drug is administered to the

food-producing animal, which is later slaughtered,

and its tissues, known to contain bound residues,

are fed to laboratory animals such as rats. Detection

of radioactivity in the plasma (for example) of these

animals would indicate that the bound residues are

bioavailable and, as a result of digestive processes,

have been released for subsequent absorption. Chem-

ical methods using solvent extraction and acid–base

treatments investigate the ease with which bound

residues can be released. These methods then deter-

mine whether or not the contribution from bound

residues needs to be taken into account in the MRL

setting procedure.

0029As indicated earlier, microbiological safety testing

has been proposed for use in the hazard assessment

process and indeed has been incorporated into

some testing guidelines, including those of the EC.

The requirement for such testing is based on the

premise that residues of some antibiotic and antimi-

crobial compounds may have the potential to affect

adversely the gastrointestinal flora of the consumer,

either by favoring the growth of resistant bacteria or

by allowing the growth of organisms not normally

found in any numbers in the gastrointestinal tract, by

reducing the numbers of other organisms that nor-

mally suppress them. This is an extremely controver-

sial area of safety assessments for two main reasons.

First, despite the use of antibiotic and antimicrobial

drugs in veterinary medicine for many years, there is

no evidence to suggest that harmful effects have

arisen in the human population as a result of bio-

logical changes in the gut flora. Second, the tests

proposed to identify these effects have not been valid-

ated, so that even if the effects do exist, it is not

known whether or not the proposed tests would actu-

ally detect them.

0030There are three tests currently available. Human

volunteer studies involve the administration of the

drug and subsequent examination of feces and

the oral cavity for changes in floral composition. The

major alternative involves the use of germ-free

rodents in which human gut flora have been seeded

into the gastrointestinal tract. These are then given

the drug under investigation and changes in the gut

Pigs

Rabbits

Horses

Fish

Bees Honey

Poultry

Game birds

Pigeons

Eggs

Cattle

Sheep

Goats

Milk

Meat, fat, kidney, liver

fig0001 Figure 1 Major food-producing species and their products im-

portant in considering maximum residues limits (MRLs) and resi-

dues studies. Reproduced from Antibiotics and Drugs: Uses in

Food Production, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology

and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds),

1993, Academic Press.

252 ANTIBIOTICS AND DRUGS/Uses in Food Production

flora monitored. The third approach makes use of

in-vitro studies of the susceptibilities of various

types of bacteria to antibacterial drugs, before and

after exposure to low, sublethal levels of the drug. The

numerical results in terms of dose can then be

employed in the calculation of the ADI.

Residue Studies

0031 Having determined an MRL value (or values) for a

drug, it is then essential to ensure that residues in the

tissues or other products of food-producing animals

do not exceed these. This is achieved by determining

the withdrawal (or withholding) period for the drug

in question. Small groups of animals are treated with

the medicine, usually at the maximum dose recom-

mended for its use in practice. The animals are then

slaughtered in a serial manner after various intervals

to determine when residue levels fall below the MRL.

This time period for depletion of residues to below

the MRL is then usually chosen as the withdrawal

period; animals must be retained unmedicated during

this time as the minimum interval between drug ad-

ministration and slaughter. Where appropriate, milk,

eggs, and honey must be discarded until this min-

imum time has elapsed.

Enforcement

0032 There is little point in progressing through the various

procedures detailed above if the withdrawal period is

ignored, and unacceptable levels of residues result.

There is often pressure to ensure that animals are

sent to slaughter at particular times, and this can

lead to abuse.

0033 To ensure that withdrawal periods are observed,

most countries operate some form of residues surveil-

lance scheme. In the UK, for example, over 40 000

samples are taken annually from slaughterhouses,

and these are tested for residues of various veterinary

drugs in compliance with the requirements of the EC

Residues Directive (86/469/EEC). Other EC member

states carry out similar surveillance in order to

comply with the requirements of this directive. The

system allows enforcement officers to trace carcases

back to farms to determine why the problem arose

and, where necessary, to take legal proceedings

against offenders.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission

0034 The Codex Alimenatarius Commission is a joint

WHO and FAO body, and one of its objectives is

to ensure that food of plant and animal origin

worldwide is safe for human consumption. It has

recently commenced work on establishing MRLs for

veterinary drugs, having been involved for many

years in setting these for pesticide residues. The

Codex is advised on toxicological and residues issues

by JECFA, the published scientific reports of which

summarize the major conclusions and the proposed

MRLs.

0035Given the international standing of the Codex

system and of the JECFA, it seems likely that the

MRL values that it promulgates will find their way

eventually into various national regulations. In par-

ticular, it offers a basis for scientific assessment not

currently available in some poorer and less developed

nations.

Concluding Considerations

0036In most countries of the world, veterinary medicines

are assessed for their ability to induce toxic effects,

and these effects and the doses that produce them are

taken into account when calculating the ADI, which

is in turn used to determine an MRL value or values.

Residues studies are then used to determine when

levels of the drug and its metabolites are depleted to

below the MRL in food-producing animals. Residues

surveillance is essential to ensure that withdrawal

periods are observed and, moreover, to ensure that

the consumer is not exposed to unacceptable residue

levels.

See also: Hormones: Steroid Hormones; Legislation:

Codex; Parasites: Occurrence and Detection

Further Reading

Anonymous (1987) Anabolic, Anthelmintic and Antimicro-

bial Agents. The 22nd Report of the Steering Group on

Food Surveillance. The Working Party on Veterinary

Residues in Animal Products. London: Her Majesty’s

Stationery Office.

Booth NH and McDonald LE (eds) (1988) Veterinary

Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 6th edn. Iowa City,

IA: Iowa State University Press.

Brander GC, Pugh DM, Bywater RJ and Jenkins WL (1991)

Veterinary Applied Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 5th

edn. London: Ballie

`

re Tindall.

Commission of the European Communities (1989) The

Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the European

Community, vol. V. Luxembourg: Office for Official

Publications of the European Communities.

European Federation of Animal Health (Seminar) (1989)

Rationale view of antimicrobial residues. An assessment

of human safety. Advances in Veterinary Medicine, sup-

plement to the Journal of Veterinary Medicine No.42.

International Programme on Chemical Safety (1987) Prin-

ciples for the Safety Assessment of Food Additives

and Contaminants in Food. Environmental Health

Criteria 70. Geneva: World Health Organization.

ANTIBIOTICS AND DRUGS/Uses in Food Production 253