Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

enzyme-mediated reactions in which carbon dioxide

and sulfates serve as the external electron acceptors.

These three processes of obtaining energy form the

basis for the various biological waste water treatment

processes.

000 4 Biological treatment processes whether aerobic or

anaerobic are typically divided into two categories:

suspended growth systems and fixed-film systems.

These processes can be batch, semicontinuous, or

continuous flow processes. Suspended growth systems

are more commonly referred to as activated sludge

processes, of which several variations and modifica-

tions exists. Fixed-film biological processes differ

from suspended growth systems in that microorgan-

isms attach themselves to a medium that provides an

inert support. Biological towers (trickling filters) and

rotating biological contactors are the most common

forms of fixed-film processes. (See Effluents from

Food Processing: On-Site Processing of Waste.)

Activated Sludge

0005 The activated sludge process is the most commonly

employed treatment process for the degradation of

organics in waste water from the food-processing

industry. This article will review activated sludge

microbiology, identification techniques of filament-

ous microorganisms, nonfilamentous microbial prob-

lems, higher life forms, and current activated sludge

control measures.

Activated Sludge Microbiology

0006 The applicability of biologically treating a particular

waste water is a function of the biological degrad-

ability of the dissolved organic chemical constituents

present in the waste water. The degradation rate of

a specific organic compound is a function of the

molecular structure of that particular compound,

the genera and species (type) of microorganisms util-

izing it as a food source, and the time required for the

microorganisms to develop the enzymes necessary for

substrate utilization.

000 7 The basic mechanism for removal of organic

materials from waste water by biological treatment

processes can be represented by three chemical reac-

tions occurring simultaneously: energy, synthesis, and

endogenous respiration. Energy and synthesis are

often referred together as oxidative assimilation,

and involve the consumption by microorganisms of

the organic materials present in the waste water. A

portion of this organic material is used as fuel to

supply energy for metabolism, while the remaining

material provides building components resulting in

the formation of new cellular material. Thus, the

organic material can be considered as food or sub-

strate consumed by the microorganisms, with the

production of carbon dioxide.

0008In the initial growth phases of a batch-fed bio-

logical process when organic matter (food) is present,

oxidative assimilation is the primary reaction; how-

ever, as the food supply diminishes, the organic matter

within the sludge is utilized and results in endogenous

respiration as the predominant reaction. In the con-

tinuous fed complete-mix activated sludge process,

both oxidative assimilation and endogenous respir-

ation occur simultaneously. The degree of oxidative

assimilation compared with endogenous respiration is

a function of the operating conditions. Higher organic

loading rates favor oxidative assimilation, whereas

lower organic loading rates favor endogenous

respiration.

0009The reactions of energy, synthesis, and endogenous

respiration can be represented by the following

simplified equation (eqn (1)):

+ O

2

Microorganisms

New

microorganisms

+

CO

2

+ H

2

O+ energy.

Organic

matter

(1)

This equation is a simplification of the biochemical

equation (and of microbial growth); it is qualitative,

since no numerical coefficients are included, and sig-

nificant elements have also been omitted. Nitrogen,

phosphorus, and trace quantities of other elements

have been eliminated from the left side of the equa-

tion. Typically, the heterogeneous population of the

active biomass in the activated sludge process consists

of 95% bacteria and 5% higher life forms such as

rotifers, nematodes, protozoa, etc. The main purpose

of the biota in the mixed liquor is to remove (metab-

olize) the soluble organics in the influent waste water

stream and create floc forming bacteria that will settle

under gravity in the secondary clarifier, thus leaving a

clear supernatant (effluent) that can be discharged.

0010Situations may arise where not all the bacteria

become floc-formers, thereby causing a turbid final

effluent. Certain waste water streams can contribute

to dispersed bacterial growth, single-celled free-

floating bacteria, and the proliferation of filamentous

microorganisms. It must be noted that filamentous

bacteria are not always the main culprit for bulking

or rising sludge problems. In fact, some filamentous

organisms can assist in settling by acting as a back-

bone, whereby floc forming bacteria can grow and

attach, therefore, minimizing the potential for shear-

ing of the floc. Also, the presence of some filaments

can and do act as a ‘catch all’ filter for small particles

EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes 1977

that do not settle in the final clarifier. Filamentous

bulking most often occurs when filaments are

present in large amounts, thereby causing sludge

compaction and settling to be hindered in the second-

ary clarifier.

Filamentous Microorganisms

0011 In most activated sludge processes, filamentous

microorganisms are routinely observed and actually

belong in the microbial population. Their presence in

the activated sludge process may actually contribute

to a good quality effluent as long as their abundance

is held to a minimum. A massive growth of filament-

ous microorganisms most often leads to bulking

problems in the final clarifier, thereby leading to the

deterioration of effluent quality. At least 25–30 types

of filamentous microorganisms have been found to

exist in activated sludge with 10–12 types being the

most predominant. Though much effort and research

have been expended trying to classify and name all

the filamentous microorganisms, the task has yet to

be completed. Consequently, unknown filamentous

microorganisms (due to a lack of specific genus

names) are indicated by a four-digit number. The

occurrence of various types of filamentous micro-

organisms has been correlated with waste water

characteristics and operating conditions, as shown

in Table 1. This type of information can be used as a

diagnostic tool to aid in the identification of potential

filamentous microorganisms and the possible reason

for proliferation. The growth of filamentous micro-

organisms is similar to normal bacterial growth

except for unicellular cell division. Separation of

two new cells does not take place with filamentous

organisms, and consequently filaments consist of

chains, long or short, of cells. In these cells, normal

cell division occurs, but the two cells stay together.

However, the presence of a sheath (hollow outer

structure) may inhibit cell separation; hence, a large

chain of many cells can develop. Usually, the cross-

walls between the cells within a filament can be

observed when performing a microscopic exami-

nation.

Identification of Filamentous Organisms

0012When bulking ofsludgeoccurs, itcanbe observed inthe

final clarifier. Prior to this, it can be microscopically

evaluated whether the bulking is due to filamentous

microorganisms and, if so, the specific type of fila-

ments. A brief description of different morphological

characteristics of filamentous organisms follows. For

detailed assessment and identification, the manual

Manual on the Causes and Control of Activated Sludge

Bulking and Foaming, by Jenkins, Richard, and Daig-

ger, is very helpful, or the computer-based rapid

Filamentous Bacteria Identification Program ‘FIL-

IDENTPro

TM

, Stover & Associates, Inc., which utilizes

an enhanced algorithm and search tree that enables the

user to identify filamentous organisms easily and re-

duces the potential for misdiagnosis, is a very good

training and identification guide.

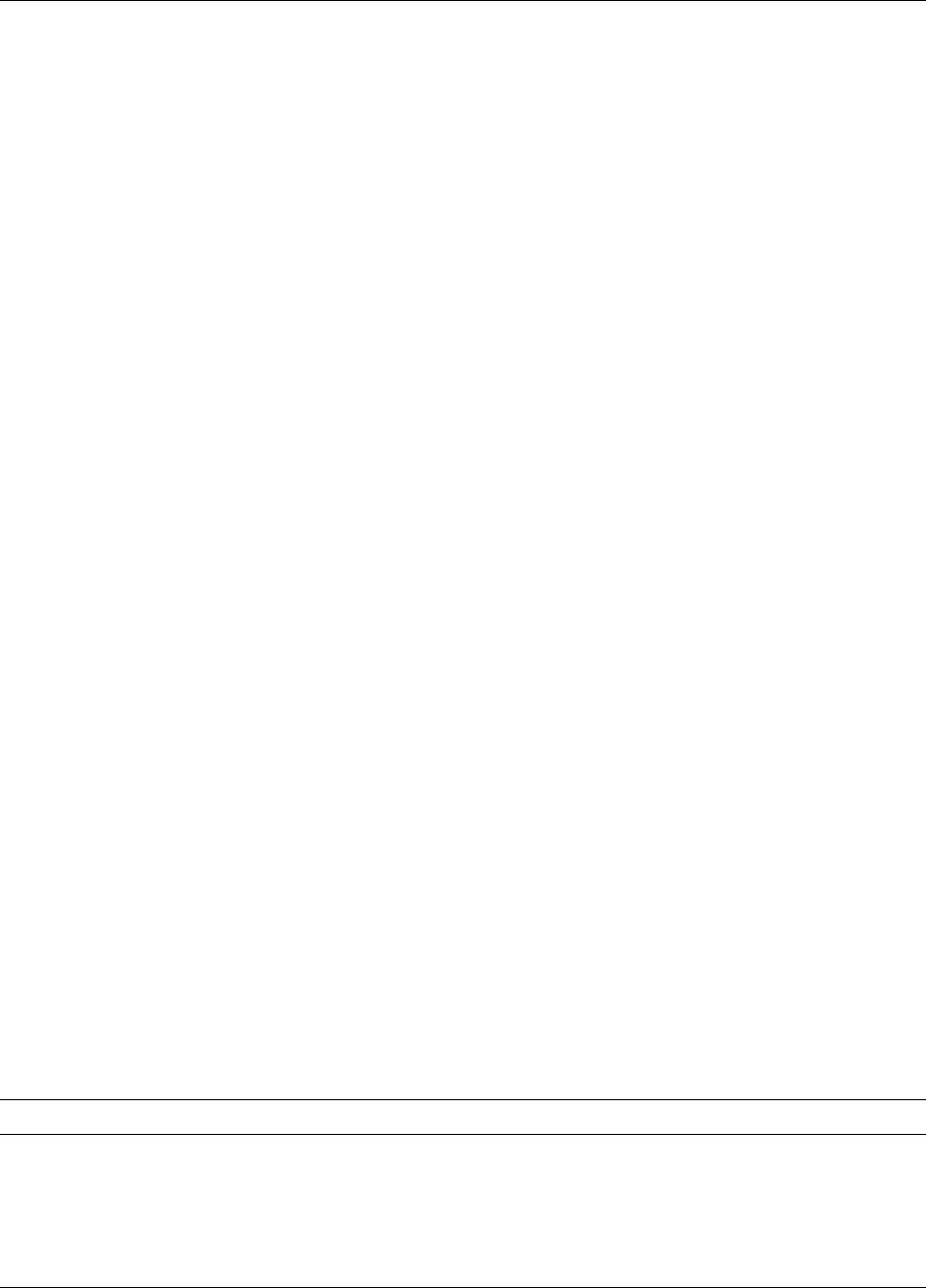

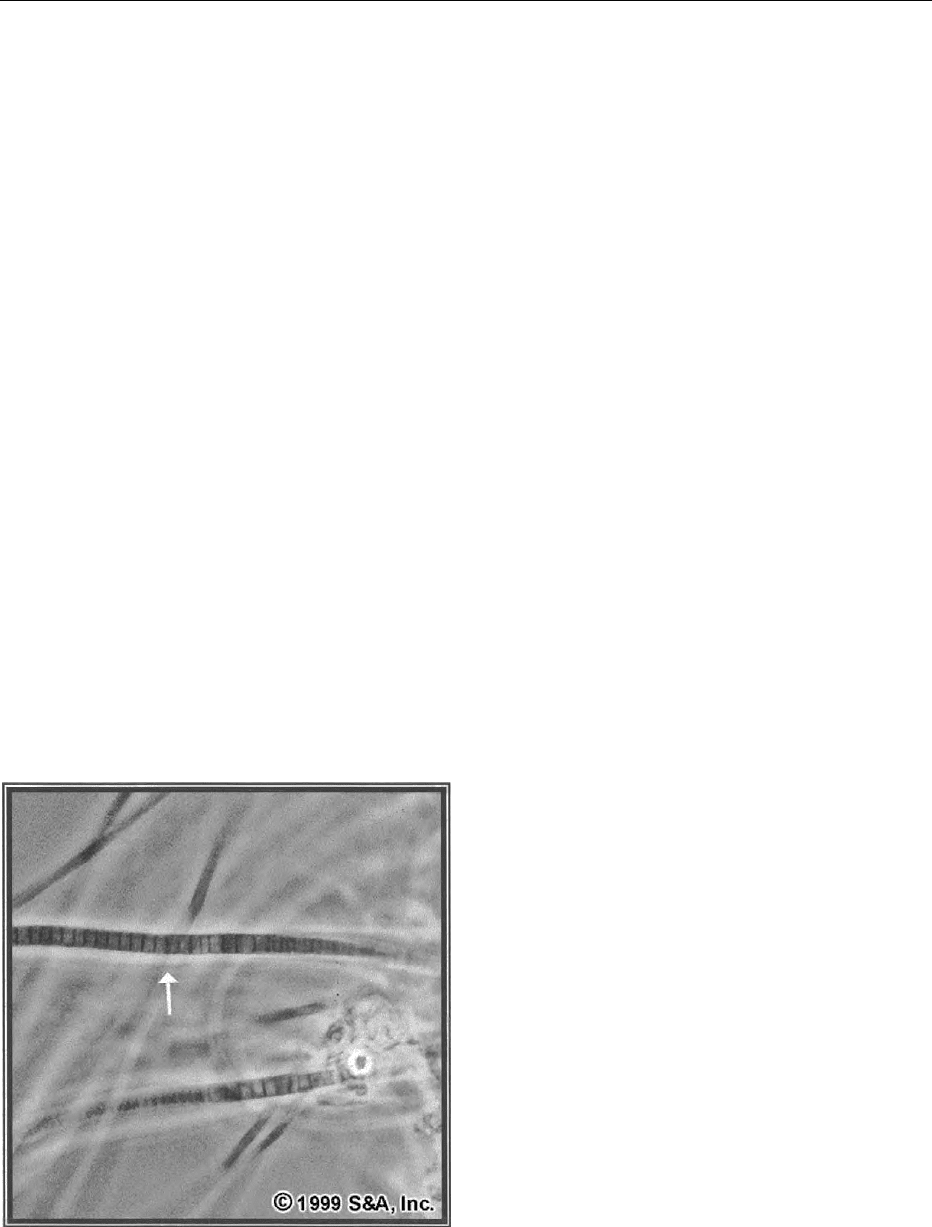

0013The size (length and diameter) and location of

filamentous microorganisms vary greatly. Filaments

may be long and stout, short and thin, protrude from

the floc, be within the floc, be free-floating in the bulk

solution, or various combinations of these, may

have attached growth adhering to the sheath

(Figure 1), and/or have an outer cylinder-shaped

clear structure in which some filamentous bacterial

cells are wrapped. However, not all filamentous

bacteria have a sheath or even attached growth. The

shape (straight (Figure 2), bent, coiled, mycelial,

smoothly curved) of the filamentous microorganism

must be noted, as well as the shape of the individual

cells within the microorganism itself. Most often,

the cells are rectangular or square, but the need

to account for all possible shapes (oval (Figure 3),

discoid, round-ended rods (Figure 4), barrel, coccus)

is essential to know in order to correctly identify the

filamentous microorganism. Other important phys-

ical characteristics that distinguish filamentous

bacteria from one another are cell inclusions, the

tbl0001 Table 1 Dominant filament types indicative of activated biosolids operation problems

Suggestedcausative condition Indicative filament types

Low DO Sphaerotilus natans, Haliscomenobacter hydrossis, type 1701

Low F/M Microthrix parvicella, Haliscomenobacter hydrossis, types 021N, 0041, 0675, 0092, 0581, 0961,

and 0803

Nitrogen and/or phosphorus deficiency Sphaerotilus natans,Thiothrix spp., type 021N; possibly Haliscomenobacter hydrossis and types

0041 and 0675

Low pH Fungi

Septic wastes Thiothrix spp., Beggiatoa spp., type 021N

From Richard MG, Jenkins D, Hao O and Shimizu G (1982) The Isolation and Characterization of Filamentous Microorganisms from Activated Biosolids Bulking.

Report No. 81–2, Sanitary Engineering and Environmental Health Research Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, with permission.

1978 EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes

presence or absence of septa, constrictions of the

outerwall, motility, rosettes formation, and whether

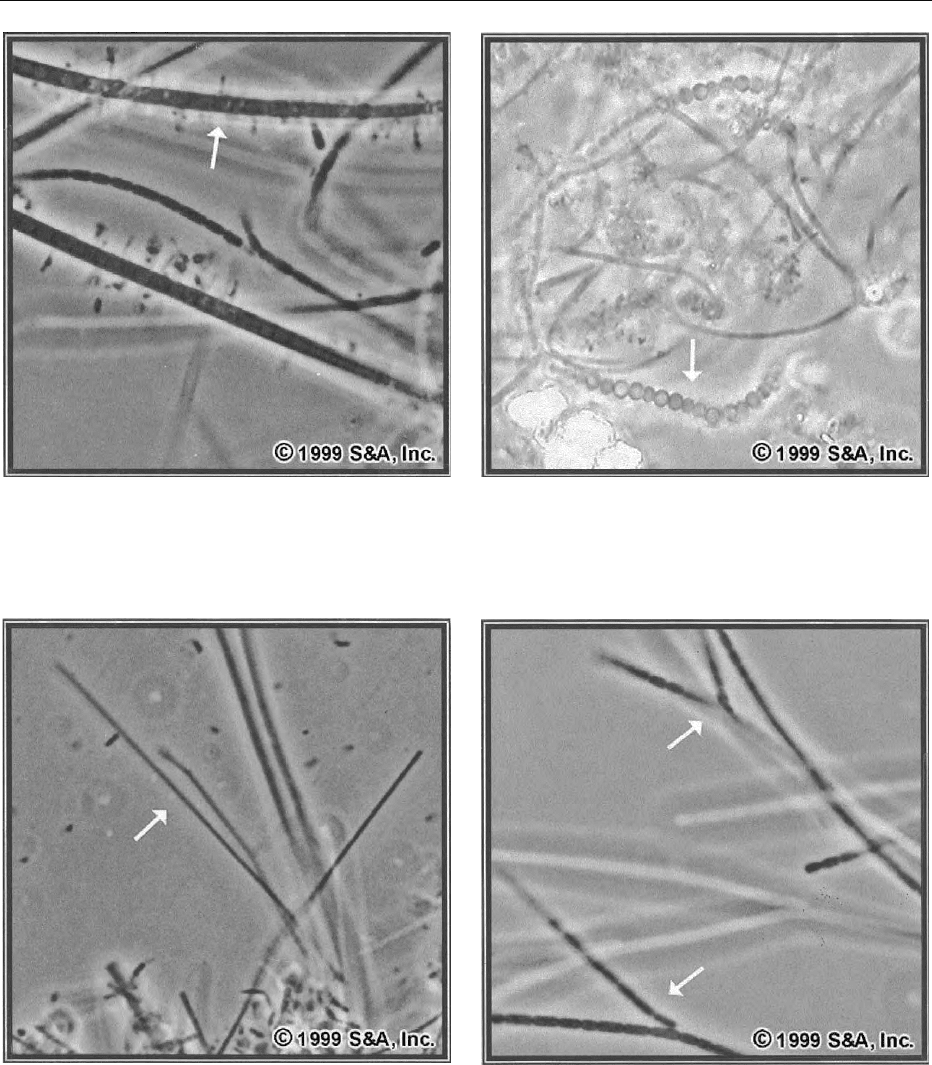

any branching is true (Figure 5) or false (Figure 4).

These physical characteristics can be determined

microscopically by using a phase-contrast microscope

at 1000.

0014In addition to identifying the physical morphology,

staining of the filamentous bacteria enhances the

identification procedure. The Gram Stain and Neisser

fig0002 Figure 2 Filamentous bacteria, Haliscomenobacter hydrossis,

indicating a rigidly straight trichome. Subject to copyright and

patent protection of Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-

IDENTPro

TM

Filamentous Bacteria Typing Program.

fig0001 Figure 1 Attached growth of epiphytic bacteria on filamentous

organism, Type 0914. Subject to copyright and patent protection

of Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Fila-

mentous Bacteria Typing Program.

fig0003Figure 3 Oval cells resembling a pearl necklace. Filamentous

bacteria, Type 1863. Subject to copyright and patent protection of

Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Filament-

ous Bacteria Typing Program.

fig0004Figure 4 (see color plate 47) Round-ended rods. False trich-

ome branching. Note the appearance of the trichome branches

being ‘stuck’ together. False trichome branching does not have

contiguous cytoplasm between the branches. Filamentous bac-

teria, Sphaerotilus natans. Subject to copyright and patent protec-

tion of Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Filamentous Bacteria Typing Program.

EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes 1979

Stain are used extensively in the bacterial character-

ization process. The results are expressed as Gram-

positive or -negative and Neisser-positive (Figure 6)

or -negative. Other specialized slide preparation tests

include:

1.

0015 Sulfur oxidation test – Ability of the bacterium to

store sulfur granules.

2.

0016 Crystal violet stain – Used for determining

whether a filamentous microorganism contains a

sheath.

3.

0017 India ink reverse stain – Indicates the presence or

lack of exocellular polymeric material (extracellu-

lar polysaccharides).

4.

0018 PHB stain – Detects intracellular storage of poly-

hydroxybutyrate.

Microscopic examination of the Gram, Neisser, and

PHB stains should be at 1000 magnification

with direct illumination (bright field). The India

ink reverse stain should be observed at 100

magnification with phase contrast. Crystal violet and

the sulfur oxidation test should be viewed at 1000

magnification phase contrast. A general outline is pre-

sented in Table 2, indicating important morphological

characteristics and stains for the proper identification

or typing of filamentous bacteria.

0019 Filamentous bacteria serve as indicator organisms

that, if correctly identified, allow for proactive meas-

ures to be initiated, thereby reducing the potential

fig0005 Figure 5 (see color plate 48) True trichome branching. True

branching refers to contiguous cytoplasm between the branches.

Filamentous bacteria, nocardia form. Subject to copyright and

patent protection of Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-

IDENTPro

TM

Filamentous Bacteria Typing Program.

fig0006Figure 6 Neisser stain of filamentous bacteria. Blue–violet

trichome indicates a positive reaction to the Neisser stain. Sub-

ject to copyright and patent protection of Stover & Associates,

Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Filamentous Bacteria Typing

Program.

tbl0002Table 2 Filamentous bacteria identification techniques

Morphology

I. Branching

1. True

2. False

II. Motility

III. Inclusions (granules)

1. Sulfur

2. Polyhydroxybutyrate

IV. Septa

V. Shape of filament

1. Straight

2. Bent

3. Coiled

VI. Attached growth

VII. Constrictions

VIII. Shape of cells

1. Spherical or coccus

2. Rod

3. Spiral

4. Oval

IX. Sheathed

X. Rosettes

Stains

I. Neisser

1. Positive

2. Negative

II. Gram

1. Positive

2. Negative

III. Crystal violet

IV. Polyhydroxybutyrate

V. India ink reverse

VI. Sulfur oxidation test

1980 EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes

for process failure. For example, identification of the

filament, O21N (Figure 7) can indicate possible ni-

trogen-deficient operating conditions with high-

strength food-processing waste waters.

0020 Once filamentous bacteria become established, they

possess a competitive advantage over other organisms

relative to substrate utilization and growth. Hence, it is

very important to identify the specific filament(s) that

cause, or contribute to, bulking at each specific waste-

water treatment plant. Early detection of site-specific

problematic filamentous microorganisms often leads

to heading-off of a bulking sludge condition before

serious problems arise.

Nonfilamentous Microbial Problems

0021 Though filamentous microorganisms play an import-

ant role in most activated sludge bulking episodes,

nonfilamentous microbial growth can also cause

negative impacts relative to proper settling and

growth of the mixed microbiological culture in the

activated sludge process. These include: dispersed

growth, toxicity, floating sludge (denitrification) and

nutrient deficiency.

1.

0022 Dispersed growth is generally characterized by

single-celled bacteria in which floc development

is negated and settling does not occur. This type

of growth leaves behind a turbid, murky effluent.

Most often, common dispersed growth problems

are associated with industrial waste-water treat-

ment facilities where the influent waste stream

consists of soluble readily biodegradable organics

operating at a high food-to-microorganism (F/M)

ratio. Thus, the microorganisms are growing in a

high log growth-rate phase that does not favor

a floc forming settling sludge. Other possible

sources of dispersed growth are nutrient (nitrogen

and phosphorus)-deficient growth conditions and

toxicity such as chronic heavy metals toxicity and

associated deflocculation.

2.

0023Toxicity or toxic shock loads can create severe

operations problems in the activated sludge pro-

cess. Toxicity implies reduced treatment efficiency

and biological upset conditions that stem from the

death of a microbe or metabolic impairment. In-

dustrial waste streams often contain compounds,

such as cleaning agents and/or surfactants that, in

sufficient concentrations, can cause cell inhibition

or, even worse, toxicity. Several microscopic bio-

indicators can be employed to diagnose these types

of problems, as follows:

.

0024loss or kill of higher life forms and/or protozoa;

.

0025biomass deflocculation often accompanied by

dispersed growth and foaming in the aeration

basin;

.

0026rapid increase in flagellate concentration and

activity;

.

0027loss of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD)

5

removal; and

.

0028proliferation of filamentous organisms upon

recovery from the process upset.

Depending on the severity of the toxic load, the

F/M ratio can be extremely high initially because

of the bacteriological die-off, hence further devel-

opment of dispersed growth. A spiked dissolved

oxygen uptake rate of mixed liquor can be used to

diagnose and detect toxicity especially in early

stages. Waste-water additions that decrease the

oxygen uptake rate by more than 4–5% generally

indicate microbiological inhibition.

3.

0029Floating sludge in the final clarifier is generally an

indication that the aeration system is performing

to the extent that the ammonia-nitrogen is being

oxidized to nitrite- and nitrate-nitrogen (nitri-

fication). The nitrite- and nitrate-nitrogen under

anoxic conditions in the clarifier can be reduced to

nitrogen gas and rise to the surface carrying the

biological solids with it. This floating sludge con-

dition can be generally corrected by increasing the

return sludge rate, increasing the waste sludge

rate, thus reducing the sludge inventory in the

clarifier, by increasing the F/M ratio or, possibly,

by adding specific inhibitors of the nitrification

process to the system.

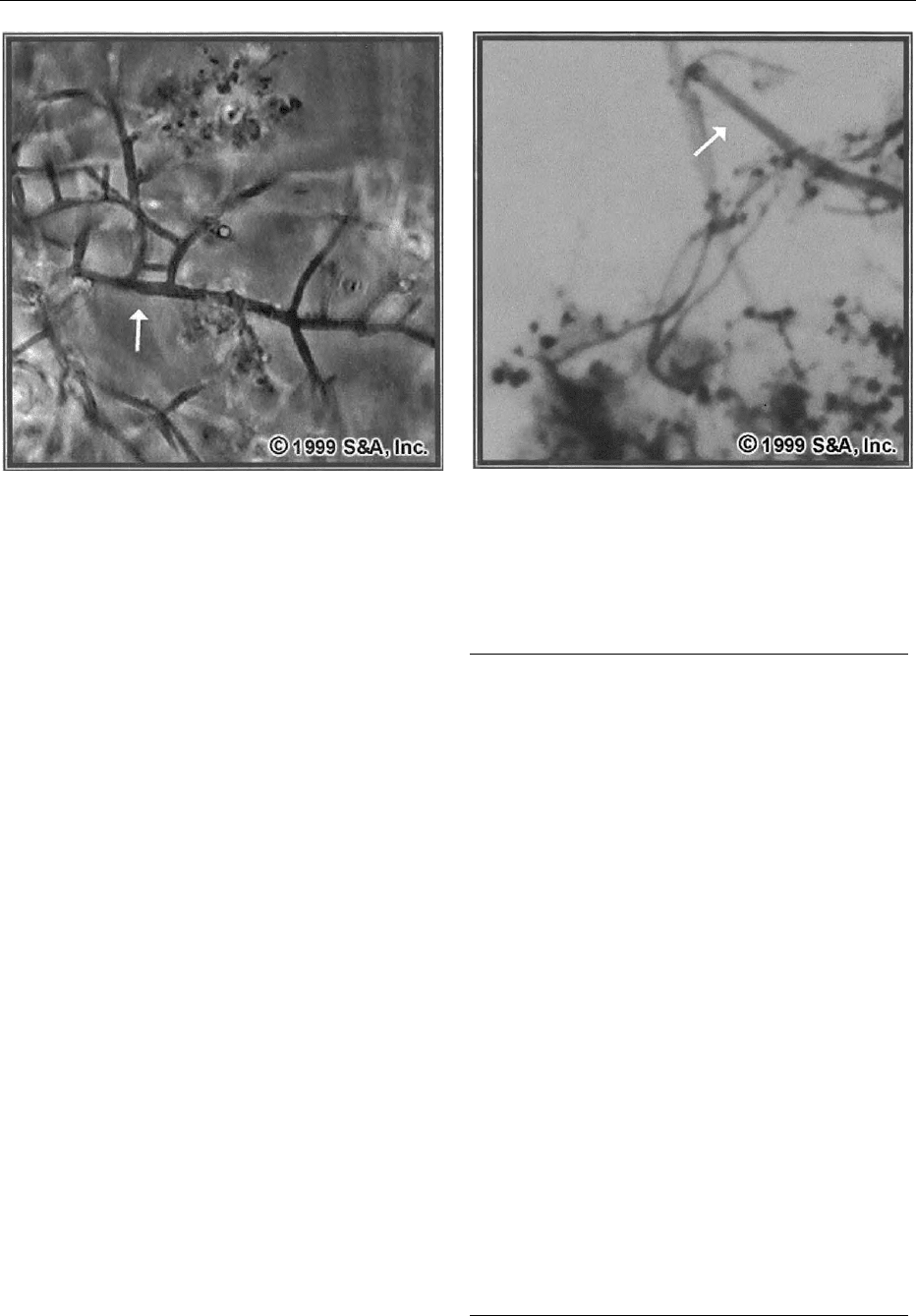

fig0007 Figure 7 (see color plate 49) Filamentous bacteria type 021N.

This slide was photographed at 1000 magnification under

phase contrast. Subject to copyright and patent protection of

Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Filament-

ous Bacteria Typing Program.

EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes 1981

4.0030 Nutrient deficiency: Micro- and macronutrient

availability is extremely important in maintaining

a healthy and active biomass in the aeration

basin. The macronutrients, phosphorus and nitro-

gen, are typically more apt to be supplemented

than the micronutrients. The need for the addition

of micronutrients is rare because of the small

concentrations required and the availability

of these nutrients in most influent waste streams.

Nutrient deficiency is usually associated with

industrial waste-water treatment plants.

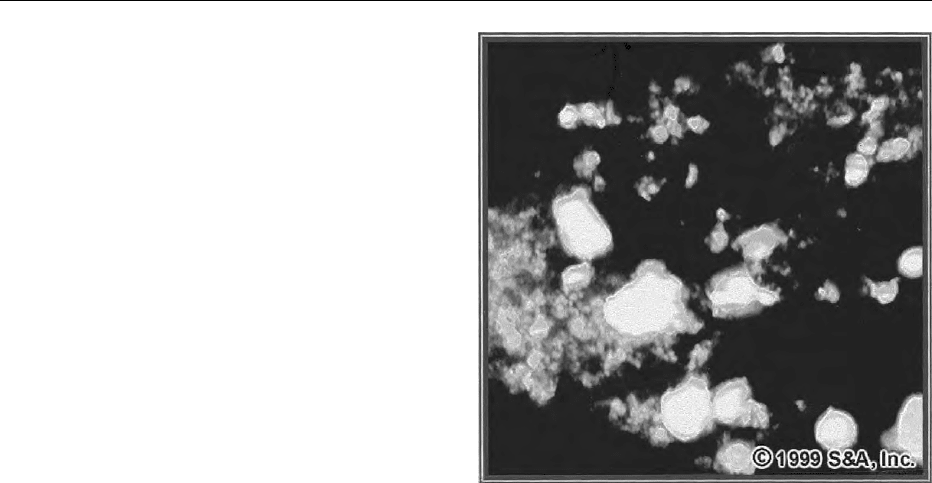

0031 The production of foam and the jelly-like

consistency of the activated sludge mixed liquor

are indicators of bulking problems associated

with nutrient deficiency. The jelly-like (slime)

consistency is a byproduct from the bacterial cell

when production of necessary cell components

such as protein is hampered because nitrogen is

not available. The slime, more commonly called

exocellular or extracellular polysaccharide, is a

metabolic shunt product with surface-active prop-

erties that can lead to foaming in the aeration

basin. Sludge grown inthis media consists of large

globular floc forms that do not settle and compact

in the clarifier. This condition can be observed

microscopically by using the India ink reverse

negative staining technique. Under normal

conditions, the ink particles penetrate deeply

within the floc, while penetration is blocked

when large amounts of exocellular polysacchar-

ides are present, resulting in a whitish ‘ghost’ ap-

pearance to the sludge (Figure 8). Certain

filamentous organisms thrive under nutrient defi-

cient conditions. The filaments most often related

to nutrient deficiency are types 0041, 021N, 0675,

and Thiothrix sp. Other filamentous bacteria may

be present also; however, these filaments are typic-

ally indicators of nitrogen- or phosphorus-limiting

conditions.

0032 The maximum theoretical amount of nitrogen

and phosphorus required for biological synthesis

is based on a BOD

5

:N:P ratio of 100:5:1. This

value can be increased or decreased, depending

on the sludge retention time (SRT), F/M ratio,

organic compounds being oxidized, etc. Maintain-

ing soluble nitrogen and phosphorus residuals

of at least 1.0 and 0.2 mg l

1

respectively, generally

allows sufficient nutrient availability. The addition

of these macronutrients to the aeration basin

should closely match the demand; however, a wide

variation in the organic loading rate can make

this task extremely difficult. Many microbiological

problems, both filamentous and nonfilamentous,

exist in activated sludge systems due to nutrient-

deficiency problems. Care should be taken to

insure that all the environmental operating condi-

tions have been properly maintained.

Protozoa and Activated Sludge

0033Effluent quality and plant performance can be related

to higher life organisms present in the aeration basin

mixed liquor. The biology of the activated sludge

aeration basin consists of protozoa, rotifers, annelids,

nematodes, and other higher life forms. Approxi-

mately 5% of the mixed liquor may be represented

by 200 species of protozoa and other higher life

forms. The protozoa is generally the most abundant

organism in the aeration basin. Protozoa are all

single-celled organisms that are hundreds of times

larger than bacteria. Therefore, they are easily viewed

under a microscope and can be used as an indicator

organism of biomass quality.

0034Locomotion is usually accomplished by external

hair-like flagella (tail) or through body movement.

Ingested food particles are usually stored inside the

vacuoles (food compartments) until enzymes break

the food down for absorption through the cell

wall. The role of these organisms varies from enhan-

cing microfloral activity and decomposition, thereby

aiding oxygen penetration, to contributing to

fig0008Figure 8 (see color plate 50) India ink staining for extracellular

polysaccharide. India ink particles penetrate the flocs almost

completely, at most leaving a small clear center. In activated

sludge containing large amounts of extracellular material (as

shown in picture), large clear areas indicate areas of low cell

density. This slide was photographed at 10 magnification. Sub-

ject to copyright and patent protection of Stover & Associates,

Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Filamentous Bacteria Typing

Program.

1982 EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes

biomass flocculation. Microscopic examination of

the biomass, when performed on a routine basis,

such as daily, provides a picture of the condition of

the biological population. Normally, microscopic

evaluation of the biological solids is made under a

100 magnification by placing a drop of biosolids on

a glass slide. Increased magnification enhances the

detail of the observed organisms. Microscopic evalu-

ation of the biomass should be performed daily to

monitor for increases or decreases in the various

types of higher life growth in the biological popula-

tion.

0035 The major groups of higher life organisms in acti-

vated sludge are: rotifers, free-swimming ciliates,

attached (stalked) ciliates, flagellates, amoeba, and

higher invertebrates such as nematodes and annelids.

The proliferation of certain organisms is dependent

upon food availability, toxicity, and operating condi-

tions. The four most common and readily observable

indicator forms of higher life and the corresponding

environmental conditions for proliferation follow:

.

0036 Flagellated protozoa: These organisms are nor-

mally oval and very small, and can be identified

by their long whip-like tails (flagella) that are used

for locomotion. The character motion of flagel-

lated protozoa is undulating and relatively slow. If

this type of higher life form is predominant, the

biological system has a relatively high unstabilized

organic content. This could indicate an unusually

high BOD

5

loading or a low mixed liquor (bio-

logical solids) concentration.

.

0037 Free-swimming ciliated protozoa: These animals

are also oval but are two to five times larger than

the flagellated protozoa. The free swimmers can be

identified by tiny hair-like cilia over their body.

They move very fast in a darting fashion. If free-

swimming protozoa are the predominant type of

higher form of life, there is probably a moderate to

low organic loading level in the system.

.

0038 Stalked ciliated protozoa: These organisms are

much larger than the two previously mentioned

and have a variety of shapes. They are equipped

with a tail (stem) that they use to attach themselves

to solid particles. Some types grow in a colony form

that appears very much like a flowering bush;

the bodies of the protozoa are located at the end

of individual stems that attach to a main stem.

Protozoa of this type can be identified by cilia

located around the opening for intake of food.

The cilia actually circulate water past the food-

intake opening. The observer may be able to

see small pinpoint particles being consumed by

these animals. Stalked ciliated protozoa will pre-

dominate in a biological system that has a low

organic level of unstabilized BOD of about

10–20 mg l

1

.

.

0039Rotifers: These are the largest of the four types of

higher life organisms discussed. They have flexible

bodies that are also equipped with cilia, used to

pull food to the rotifer as well as for locomotion,

around the food intake opening. There are many

types of rotifers, some of which have forked tails

that are used to attach themselves to solid particles

while feeding. A biological system in which rotifers

predominate normally has a low organic level of

unstabilized BOD.

0040All four forms can be observed in a system at

any given time. The observer should attempt to iden-

tify which type of higher form predominates and then

use the above guide for evaluating plant performance.

These higher forms of microscopic organisms are very

sensitive to toxic materials, and their presence or

absence can help to indicate shock loads. The higher

life forms will die before the bacteria are affected, so

that routine observations can indicate trouble before

it becomes so serious as to kill the bacteria. Also, the

protozoa and other animals are strict aerobes, and

therefore are indicators of ample dissolved oxygen.

The microscopic animals can survive under anaerobic

conditions for a few hours, but prolonged deficiencies

of dissolved oxygen will be fatal. Low pH conditions

will also cause a swift kill of the higher life forms. The

protozoa, as well as the rotifers, are predators that

continually remove small floc particles and dead

microorganisms, and aid in the development of

flocs. This predatory action keeps the bacterial popu-

lation active and contributes to effluent quality by

removing nonflocculated bacteria.

0041Reliable and stable operating conditions can be

correlated to the type(s) of higher life organisms

present in the system. Low effluent suspended solids

concentration and low turbidity are normally

achieved with a balance of free and stalked ciliates

along with rotifers. A photograph of a rotifer of the

type typically observed in activated sludge systems is

presented in Figure 9. The establishment of a mixed

microbial population in the aeration basin mixed

liquor will result in optimum activated sludge per-

formance.

Anaerobic Microbiology

0042Faculative bacteria are among the largest group of

bacteria in nature. These bacteria can function in

either an aerobic or anaerobic environment. The

most common group of facultative bacteria are the

Pseudomonas. Additional common facultative bac-

teria that have been identified in waste-water

EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes 1983

treatment systems include Alcaligenes, Achromobac-

ter, Flavobacterium, and various enteric bacteria.

0043 The obligate anaerobic bacteria cannot tolerate

dissolved oxygen. Clostridium is the major group

of strict anaerobes. Sulfate-reducing bacteria are

also strict anaerobes that belong to Desulfovibrio.

They can metabolize a wide variety of organic com-

pounds while reducing sulfates to various reduced

sulfur intermediates, including hydrogen sulfide.

The methane bacteria are also strict anaerobes that

require a highly reduced environment for metabol-

ism. They include Methanobacterium, Methanosar-

cina, and Methanococcus. Certain methane bacteria

reduce carbon dioxide with hydrogen to produce me-

thane and water, whereas others metabolize acetate.

There is strong competition between the methane

bacteria and the sulfate reducers. Even though bac-

teria are the primary microorganisms in anaerobic

environments, protozoa have been observed in some

anaerobic treatment systems. These protozoa have

been described as flagellated and ciliated protozoa.

0044 Desulfovibrio bacteria can use sulfates as their

primary source of electron acceptors. The electron

changes produce a series of reduced sulfur com-

pounds, starting with thiosulfates and working

through sulfur to sulfides. Energy transfer determines

the changes in the sulfates. In the presence of excess

organic matter that is readily metabolized by the

Desulfovibrio bacteria, the reduction reactions go

completely to sulfides as shown:

Organic matter þ SO

2

4

! H

2

S þ CO

2

: ð2Þ

The hydrogen sulfide is partially soluble. As hydrogen

sulfide is produced above its solubility level, it

diffuses out of solution into the gases in proportion

to its solubility.

0045At a pressure of 1.0 atm and a temperature of

35

C, hydrogen sulfide is soluble to a maximum

level of 2750 mg l

1

at pH 4.0. However, biological

systems operate at pH values around 7.0, and as the

pH increases above 4.0, hydrogen sulfide forms

hydrogen bisulfide, as shown:

H

2

S $ HS

þ H

þ

: ð3Þ

0046At pH 7.0, there will be approximately a 50:50

split with a total allowable sulfide concentration of

5765 mg l

1

(H

2

S þHS

). Formation of bisulfide

therefore allows more sulfides to remain in solution.

Since hydrogen sulfide is the culprit creating toxicity,

toxicity can be reduced by raising the pH above 7.0 to

drive the reaction toward bisulfide. Hydrogen sulfide

levels below 200 mg l

1

should be maintained to elim-

inate toxicity problems.

0047The relative concentrations of electron donors (or-

ganic matter) and sulfates control the end-product

formation. If the sulfate concentration is higher than

the organic matter available for metabolism, the sul-

fate reducers do not have enough electrons to reduce

the sulfates completely to sulfides. The overall reduc-

tion process can be expected to follow the pattern

shown:

Organic matter þ SO

4

!½SO

3

! SO

2

!

S

2

O

3

! S

2

! HS ! SþCO

2

: ð4Þ

The thiosulfates are readily soluble, whereas, the free

sulfur is insoluble.

See also: Effluents from Food Processing: On-Site

Processing of Waste; Microbiology: Classification of

Microorganisms

Further Reading

Campana CK and Stover EL (1990) Filamentous Bulking

Sludge Control – a Case Study. Proceedings of the Sixth

International Symposium on Agricultural and Food Pro-

cessing Wastes, 328. St. Joseph, MI: American Society of

Agricultural Engineers.

Eikelboom DH and Van Buijsen HJJ (1981) Micro-

scopic Sludge Investigation Manual. Delft, The Nether-

lands: TNO Research Institute for Environmental

Hygiene.

FIL-IDENTPro

TM

(1999) Filamentous Bacteria Identifica-

tion Program, Stillwater, OK: The Stover Group.

Jenkins D, Richard MG and Daigger GT (1984) Manual on

the Causes and Control of Activated Sludge Bulking and

Foaming. Pretoria: Water Research Commission.

fig0009 Figure 9 (see color plate 51) Unidentified species of the phylum

Rotatoria, commonly called rotifers. This slide was photographed

at 100 magnification. Subject to copyright and patent protection

of Stover & Associates, Inc., as part of the FIL-IDENTPro

TM

Fila-

mentous Bacteria Typing Program.

1984 EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Microbiology of Treatment Processes

Jenkins D, Richard MG and Daigger GT (1993) Manual on

the Causes and Control of Activated Sludge Bulking and

Foaming, 2nd edn. Chelsea, MI: Lewis.

Richard MG (1989) Activated Sludge Microbiology.

Alexandria, VA: The Water Pollution Control Federation.

Stover EL (1994) Control of Opportunistic Filamentous

Bacteria in Activated Sludge Treatment of Food Process-

ing Waste Waters. Environmentally Responsible Food

Processing, AICHE Symposium Series, vol. 90, p. 42.

Stover EL and Campana CK (1990) Operational Process

Control for High Carbohydrate Filamentous Bulking.

Proceedings of the 1990 Food Industry Environmental

Conference and Exhibition. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Tech

Research Institute.

Stover EL and Gaden TB (1999) Filamentous Bacteria Iden-

tification. Proceedings of the WEFTEC

1

99 Workshop

#110 – Waste Water Microbiology, New Orleans, LA.

USEPA (1987) Summary Report – The Causes and Control

of Activated Sludge Bulking and Foaming. Cincinnati,

OH: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Disposal of Waste Water

E L Stover, Stover & Associates, Inc., Stillwater,

OK, USA

T H Eckhoff, M&M/Mars, Inc., Hackettstown, NJ, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Waste waters produced from food-processing oper-

ations vary in general based on the class or type of

food processes; however, they share many common

characteristics. These common characteristics typic-

ally allow biological treatment processes to be used

for food-processing waste waters prior to discharge

to the environment or prior to recycle and reuse.

Water quality standards and criteria have been

developed, and are constantly being refined and up-

graded for discharge and use requirements. Existing

and new environmental laws are being enforced to

protect the aquatic environment from effluent dis-

charges. The newer regulations and approaches em-

phasize watershed-based water quality initiatives and

ecological risk assessment. Waste minimization and

waste reuse approaches are being emphasized.

Characteristics of Food-Processing

Waste Water

0002 The food-processing industry is highly diverse; this

diversity is reflected in the enormous variety of

food items produced worldwide. In general, the

classes of food processors include bakeries, candy

manufacturers, meat processors, breweries, specialty

convenience-type food processors, baby food manu-

facturers, fruit and vegetable processors, and dairies.

Each type of food-processing facility has waste water

problems endemic to the specific processes involved

and to the particular product; however, there are

common characteristics of nearly all food-processing

waste waters. Refer to individual food processes.

0003The primary waste water pollutants associated

with the food-processing industry are food product,

raw materials, solvents, detergents, cleaning agents,

and disinfectants. These constituents give rise to high

biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen

demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSS), total

dissolved solids (TDS), nutrients (primarily nitrogen

and phosphorus), pH, oil and grease, and color. In

general, food-processing waste waters by their nature

contain few, if any, toxic constituents. The US Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements pre-

clude the use of hazardous or toxic constituents in

the preparation and processing of food products.

However, these same regulations often require a

food processor to clean and disinfect equipment and

facilities with compounds that could be problematic

during waste water treatment. For example, products

that contain quarternary ammonium compounds,

which have a strong disinfectant capacity, can pose

a problem during waste water treatment if used

indiscriminately for production equipment cleaning.

For the most part, food-processing waste waters are

not considered to be hazardous to human health. A

common factor in food-processing waste waters is the

enormous volume of effluent generated. Water is used

as an ingredient in many foods, and in all parts of the

food-processing operation, including product wash-

ing, blanching, cooking, cooling, diluting, cleaning,

and sanitation. The total volume of water discharged

daily may vary greatly, from 2650 m

3

day

1

for a

bakery to 2.65 10

6

m

3

day

1

for a cannery of

comparable size.

0004Food-processing industries generally dispose of

their waste water by treatment prior to discharge

directly to a receiving stream, a publicly owned treat-

ment works (POTW), or land application site. Most

food-processing plants utilize a biological treatment

system to treat their waste water. These systems

include aerobic and anaerobic processes, either inde-

pendently or in combination. Because of the nontoxic

nature of the waste water generated in the food-

processing industry, this approach is generally very

effective. Some of the disadvantages associated with

biological treatment include the generation of bio-

logical sludge which must be disposed of, the require-

ment of a skilled treatment system operator, and the

sensitivity of biological systems to climatic change or

EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Disposal of Waste Water 1985

process upsets. Prior to discharge, the waste water

must be treated to meet certain criteria, depending

on the intended route of disposal. These discharge

criteria are discussed in the following section.

Water Quality Standards for the Disposal

of Waste Water

0005 In the USA, all waste water discharges (including

food-processing industries) are regulated at several

levels. The ultimate regulatory authority derives

from the Federal Water Pollution Control Act

(commonly referred to as the Clean Water Act, or

CWA) and is administered by the Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA), although many states have

a delegated authority (in lieu of the EPA) to enforce

the various parts of the regulations. This section dis-

cusses the basic objectives of the CWA, the adminis-

tration of water quality standards by states, and

the role of toxicity testing in evaluating water

quality. Although this discussion presents discharge

standards from a US perspective, many other coun-

tries have adopted, or will be adopting, similar ap-

proaches.

0006 Environmental regulations have progressed in a

similar fashion worldwide. Water use and waste

water disposal have presented food manufacturers

with similar problems in Central and South America,

the UK, western Europe, Central Europe, and Asia. In

the 1950s to 1970s, economic goals of manufacturers

played a more important role in a country’s economic

development than environmental concerns. As water

and waste water problems from all sectors of the

economy took on a more national spotlight, environ-

mental laws were passed in an attempt to curb the

rising tide of water pollution. Water quality studies of

rivers and lakes were begun in the 1970s, and con-

tinue today. Many countries have established waste

water discharge limitations based on water quality

standards. The European Union (EU) is attempting

to establish a framework across western and central

Europe in environmental legislation to protect rivers,

lakes, and groundwater.

0007 More stringent legislation on waste water dischar-

gers, including food processors, has evolved at varying

degrees in the many nations of Europe, states of Cen-

tral and South America, and Asia. The UK and west-

ern Europe began enacting environmental legislation

in the 1960s and 1970s. Central and Eastern Europe

followed in the 1970s and 1980s, gaining on the

experience of the USA and western Europe. Many

multinational companies now see it as their responsi-

bility and are usually required by local legislation to

provide the best water and waste water treatment

available to their facilities.

The Clean Water Act

0008The first comprehensive legislation for water pollu-

tion control was the US Water Pollution Control Act

of 1948. This law adopted principles of state–federal

cooperation in program development but limited

federal enforcement authority and federal financial

assistance. These principles were continued in the

Federal Water Pollution Control Act in 1956 and in

the Water Quality Act of 1965. Under the 1965 Act,

states were directed to develop water quality stand-

ards establishing water quality goals for interstate

waters.

0009These laws were ineffective and the industrial

boom in the USA during the 1950s and 1960s

brought with it a level of pollution never before

seen in the USA. Scenes of dying fish, burning

rivers, and thick black smog engulfing metropol-

itan areas were commonplace on the evening

news. In December of 1970, the President of the

USA created the US EPA through an executive

order in response to these critical environmental

problems.

0010Congress passed the CWA, Public Law 92–500,

on 18 October, 1972. Although prior legislation

had been enacted to address water pollution, those

previous efforts were developed with other goals

in mind. For example, the 1899 Rivers and Harbors

Act protected navigational interests (commerce),

and the 1948 Water Pollution Control Act and the

1956 Federal Water Pollution Control Act only

provided limited assistance for state and local

governments to address water pollution concerns on

their own.

0011In the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amend-

ments of 1972, Congress established the National

Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)

whereby each point source discharger to waters of

the USA was required to obtain a discharge permit.

The CWA required the elimination of the discharge of

pollutants into the nation’s waters and the achieve-

ment of fishable and swimmable water quality levels.

The NPDES program represented one of the key

components established to accomplish this task. In

addition, the 1972 amendments extended the Water

Quality Standards Program to intrastate waters and

required NPDES permits to be consistent with

applicable water quality standards. Thus, the CWA

established a combined technology-based and water

quality-based approach to water pollution control.

0012Each state administers the CWA by establishing

specific water quality standards for the water bodies

in its region. The water quality standards include a

narrative limit and a series of specific numerical limits.

Each state is required to establish narrative waste

1986 EFFLUENTS FROM FOOD PROCESSING/Disposal of Waste Water