Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

magnetic contribution K (Kerr amplitude) to the re-

flected amplitude, which is polarized perpendicular to

the regularly reflected amplitude N. By interference of

K and N the resulting vector is rotated by the (small)

angle j

K

¼K/N. For two domains with opposite

magnetization the Kerr amplitudes differ in sign. A

domain contrast is obtained by extinguishing the

light of one domain by the proper setting of the

analyzer (Fig. 2(b)). If K and N differ in phase,

the rotation is connected with some ellipticity. In this

case the ellipticity of the darker domains should be

removed by a phase-shifting compensator (such as

a rotatable quarter-wave plate) to improve the

contrast.

For every magnetization configuration the light

incidence has to be properly chosen to generate a

Lorentz motion that results in a detectable rotation.

It turns out that the Kerr rotation is proportional to

the magnetization component parallel to the reflected

light beam. This rule immediately shows that do-

mains magnetized parallel to the surface require ob-

lique illumination with the plane of incidence parallel

to the magnetization axis for maximum contrast

(longitudinal Kerr effect), while the contrast of per-

pendicularly magnetized domains becomes strongest

at perpendicular incidence (j ¼0, polar Kerr effect).

The separation of polar and in-plane magnetization

components is possible by different microscope set-

tings as demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Important for good domain visibility is the size of

the usable signal and this also determines the signal-

to-noise ratio in video systems. The relative signal S,

i.e., the difference between the intensities of bright

and dark domains, is derived (Hubert and Scha

¨

fer

1998) as

S E4bKN ð2Þ

Three important properties should be noted: (i) the

Kerr signal is a linear function of the Kerr amplitude

K and therefore of the respective magnetization com-

ponents according to Eqn. (1); (ii) the (often weak)

Kerr signal can be enhanced by increasing the anal-

yzer angle b beyond j

K

, allowing an increase in the

signal-to-noise ratio and adjusting the sensitivity of

the detector; and (iii) the ‘‘visibility’’ of domains is

determined by the Kerr amplitude and not by the

Kerr rotation.

Although K depends on material constants, it can

be enhanced in materials where the incoming light is

not completely absorbed by magnetooptical interac-

tion but ‘‘uselessly’’ reflected to some extent. Antire-

flection coatings increase the absorbed intensity

(based on interference effects), proportionally raising

K and thus the useful signal (Fig. 4). Effective di-

electric coatings are ZnS for metals and MgF

2

for

oxides. As the Kerr effect is generally weak, this gain

should not be relinquished even if digital image

processing is applied.

3. Contrast Enhancement by Image Processing

A significant enhancement of magnetic contrast is

possible by video microscopy and digital image

processing. The standard procedure (Fig. 5) starts

with a digitized image of the magnetically saturated

state, where in an external a.c. or d.c. magnetic field

all domains are eliminated. This background (refer-

ence) image is subtracted from a state containing

domain information, so that in the difference image a

Figure 3

Domains in a coarse-grained NdFeB crystal in which the

magnetization axes of the different grains are misaligned

relative to the surface as sketched in (c); (a) the

magnetization components perpendicular to the surface

(polar components) can be imaged separately at

perpendicular incidence. At oblique incidence polar and

in-plane components show up simultaneously. When the

illumination direction is rotated by 1801, the polar Kerr

effect does not change sign, whereas the longitudinal

effect does. By forming the image difference the polar

contrast disappears, leaving just in-plane contrast as

shown in (b).

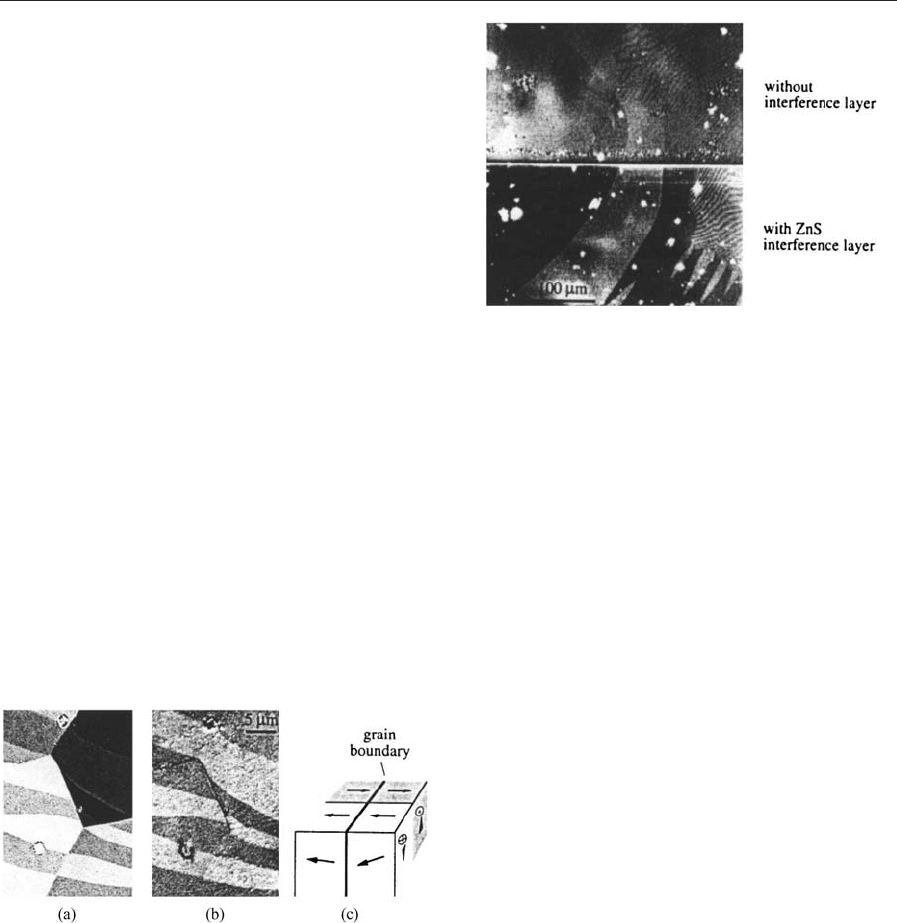

Figure 4

Effect of a dielectric antireflection coating on the Kerr

contrast, demonstrated for an amorphous ribbon with

and without a ZnS interference layer.

370

Kerr Microscopy

clear micrograph of the domain pattern is obtained

which can be digitally enhanced, free of topographic

structures.

The difference technique opens further experimen-

tal possibilities. For example, in Fig. 6 a domain im-

age (Fig. 6(a)) is subtracted from an image where

changes in the pattern are induced by a magnetic

field. In the difference image (Fig. 6(b)) only those

areas where the changes occur show a contrast. Such

observations give hints as to the local variation of

coercivity or to the amplitude of domain wall motion.

4. Quantitative Kerr Microscopy

Due to its linearity and direct sensitivity to m, the

Kerr effect can be used for quantitative determination

of the magnetization direction (Rave et al. 1987). The

Kerr intensity has a sinusoidal dependence on the

direction of the magnetization vector (Fig. 7). This

sensitivity function is obtained by measuring the in-

tensity of well-defined domains or saturated states.

The intensity of unknown domains can then be com-

pared with the calibration function and so the angle of

m in the surface can be measured. The problem is that

due to the sinusoidal dependence there are two pos-

sible angles for a given domain intensity. To resolve

this ambiguity, the domain pattern of interest has to

be imaged twice under different sensitivity conditions

that should be shifted by 901 (e.g., by choosing two

orthogonal planes of incidence). The method can only

be applied to soft magnetic materials for which no

polar magnetization components are present at the

surface.

5. Depth-selective Microscopy

The magnetic information depth of the Kerr effect

is about 20 nm in metals. A quantification of this

depth sensitivity has to consider the phase of the

magnetooptic amplitude (Tra

¨

ger et al. 1992). The

total magnetooptical signal can be seen as a super-

position of contributions from different depths,

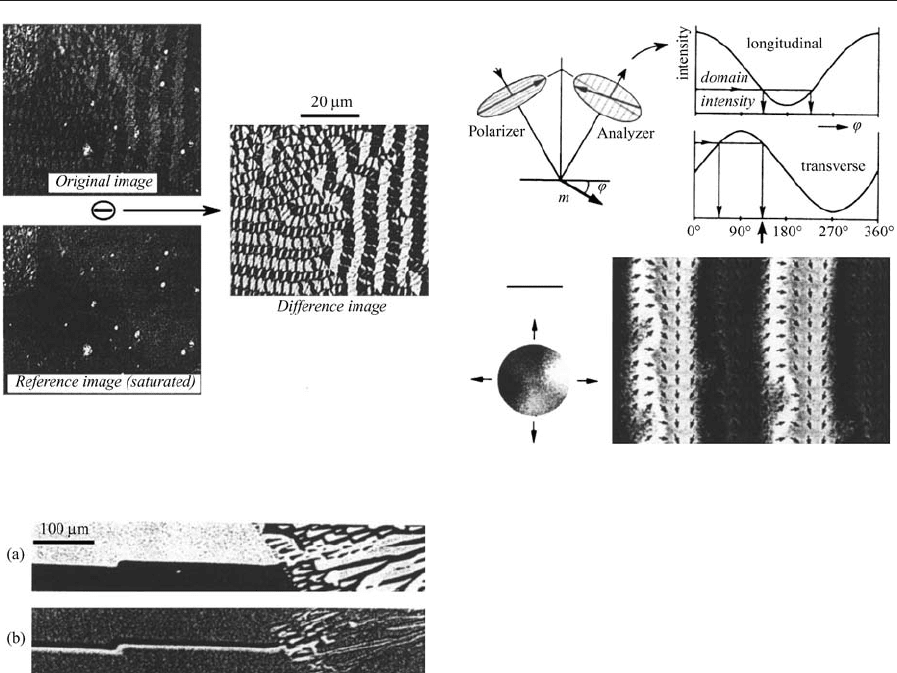

Figure 5

The difference technique for contrast enhancement.

Stress-induced domains on an iron-rich metallic glass in

the longitudinal Kerr effect are shown.

Figure 6

The kinetics of a domain pattern in a transformer sheet:

the starting configuration (a) is subtracted from the

image of a state in which the sample is subjected to an

alternating magnetic field. The moving domain walls

become visible by a black and white contrast in the

dynamically averaged difference image (b).

Figure 7

Quantitative Kerr microscopy: by imaging a domain

pattern under two complementary Kerr sensitivities and

comparing its intensities with the corresponding

calibration functions, the magnetization vector field can

be quantitatively measured. The example shows

domains on an amorphous ribbon. A vector plot and

color code can be used for presentation.

371

Kerr Microscopy

which are damped exponentially and which differ in

phase according to a complex amplitude penetration

function (Fig. 8(a)).

These phase differences can be exploited in Kerr

microscopy. Using a rotatable compensator, the phase

of the Kerr amplitude, generated at a certain depth,

can be adjusted relative to the regularly reflected light

amplitude (note that a detectable Kerr rotation is

only possible if K and N are in-phase). In this way

light from selected depth zones can be made invisi-

ble if their Kerr amplitude is adjusted out-of-phase

with respect to the regular light. In sandwich films,

consisting of ferromagnetic layers that are inter-

spaced by nonmagnetic layers, the zero of the infor-

mation depth can be put somewhere into the middle

of one layer such that the integral contributions of

this layer just cancel, leaving only contrast from the

other layer (Fig. 8(b)). This kind of layer-selective

Kerr microscopy is demonstrated in Fig. 8(c) for

an Fe–Cr–Fe sandwich sample (see also (Scha

¨

fer

1995)).

6. Other Magnetooptical Effects

Two other magnetooptical effects can be used in a

Kerr microscope: the Voigt effect and the gradient

effect (Scha

¨

fer and Hubert 1990). Both effects appear

at perpendicular incidence (where a Kerr contrast of

in-plane domains is not possible) and require a com-

pensator for adjustment. The Voigt effect is quadratic

in the magnetization components, so that only do-

mains magnetized along different axes show a con-

trast, while the gradient effect is a birefringence effect

that depends linearly on magnetization gradients.

Both effects (in combination with the Kerr effect) are

helpful in the analysis of domains in cubic materials

such as epitaxial thin-film systems by considering

their contrast laws and depth sensitivities (see

(Scha

¨

fer 1995) for an overview). The gradient effect

can also favorably be applied to image fine transi-

tions and domain modulations.

7. Dynamic Domain Imaging

Domain dynamics can be observed visually as fast as

the eye can follow. Recording periodic processes with

long exposure times yields zones of intermediate con-

trast that may give valuable information at least on

the amplitudes of wall motion (see Fig. 6).

Periodic magnetization processes can be observed

stroboscopically either by a triggered video camera or

by a pulsed light source. Triggering the light or cam-

era pulses with precise timing relative to a field pulse

and sweeping the delay time yields a series of corre-

sponding pictures of periodic or quasi-periodic proc-

esses (Peteket al. 1990).

8. Conclusions

Kerr microscopy is a versatile method for the exper-

imental analysis of magnetic microstructures, only

limited by resolution down to a few tenths of a micro-

meter. Enhanced by image processing, magnetic

domains on virtually all relevant materials can be

imaged. The dynamic capability and the compatibility

with arbitrary applied fields make Kerr microscopy

ideally suited for the investigation of magnetization

processes. Due to the direct sensitivity and linear

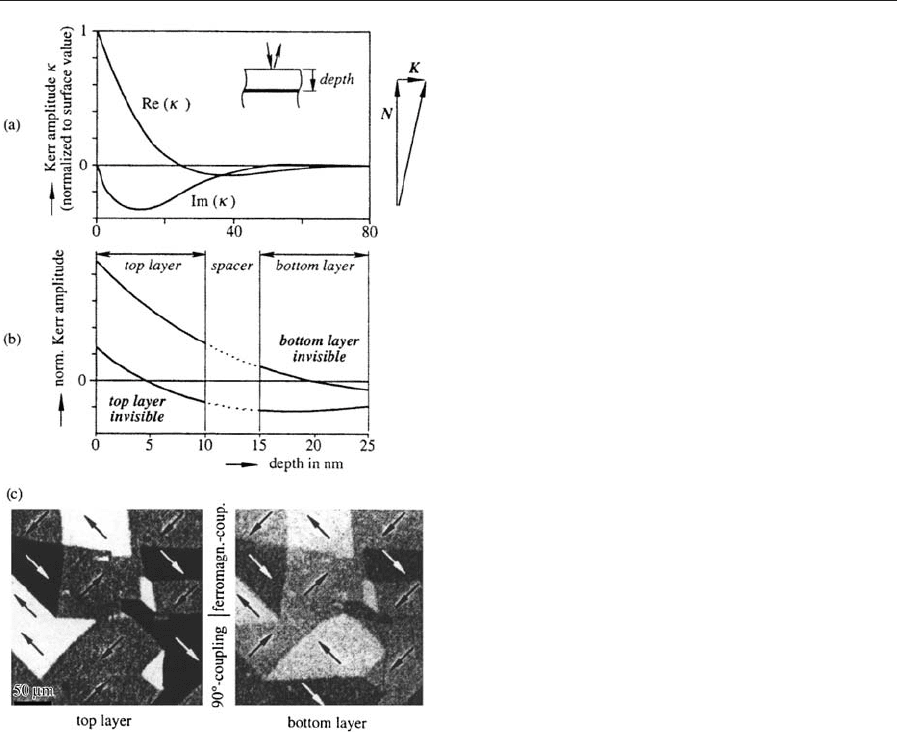

Figure 8

(a) Depth-sensitivity of the Kerr amplitude in iron. The

relative phase of K and N was selected so that N is

allowed to interfere with the K generated right at the

surface; (b) proper phase selection allows layer-selective

Kerr imaging on thin-film sandwiches; (c) a (100)-

oriented Fe (10)–Cr (E0.5)–Fe (10 nm) trilayer,

showing ferromagnetic and biquadratic (901) coupling in

one image. Note that the contrast of the bottom layer is

reduced due to absorption.

372

Kerr Microscopy

dependence on the magnetic polarization, the method

allows the quantitative determination of magnetiza-

tion vector fields at the surface of soft magnets by

calibrating the contrast. In favorable sandwich struc-

tures, layer-selective imaging is possible within a

depth-sensitivity range of about 20 nm in metals. On

bulk materials, however, it is just the surface region

that can be seen (like in most other domain observa-

tion techniques). Here often theoretical arguments

combined with domain studies in magnetic fields are

required to obtain a three-dimensional understanding

of the magnetic microstructure.

See also: Magneto-optics: Inter- and Intraband

Transitions, Microscopic

Bibliography

Hubert A, Scha

¨

fer R 1998 Magnetic Domains. The Analysis of

Magnetic Microstructures. Springer, Berlin

Petek B, Trouilloud P L, Argyle B E 1990 Time-resolved do-

main dynamics in thin-film heads. IEEE Trans. Magn. 26,

1328–30

Rave W, Scha

¨

fer R, Hubert A 1987 Quantitative observation of

magnetic domains with the magneto-optical Kerr effect. J.

Magn. Magn. Mater. 65, 7–14

Scha

¨

fer R 1995 Magneto-optical domain studies in coupled

magnetic multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 148, 226–31

Scha

¨

fer R, Hubert A 1990 A new magnetooptic effect related to

non-uniform magnetization on the surface of a ferromagnet.

Phys. Status Solidi A 118, 271–88

Tra

¨

ger G, Wenzel L, Hubert A 1992 Computer experiments on

the information depth and the figure of merit in magneto-

optics. Phys. Status Solidi A 131, 201–27

R. Scha

¨

fer

IFW-Dresden, Germany

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions:

Transport Phenome na

The proximity of the 4f or 5f shell of certain lantha-

nide and actinide elements to the Fermi level gives

rise to numerous unusual physical properties at low

temperature. Among them are heavy fermion be-

havior and superconductivity, intermediate valence,

Fermi- and non-Fermi-liquid as well as reduced mag-

netic moments in a magnetically ordered ground

state. The outweighing number of such phenomena is

attributed to a particular interaction of the conduc-

tion electron spin

~

s with the total angular momentum

~

j of the rare earth elements, known as the Kondo

effect (Kondo 1964). Here,

~

s

~

j scattering causes an

intermediate stage and as a consequence thereof a

spin-flip process. One manifestation of this effect

has been known since the early 1930s from a lnT

contribution to the electrical resistivity r(T), ob-

served for 3d magnetic impurities diluted in a non-

magnetic host. When this term is added to the

phonon contribution of such a system, it is sufficient

to explain the well-known minimum in r(T).

1. Basic Features of Transport Phenomena in

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions

The physics of Kondo systems and heavy fermions is

usually accounted for in terms of the Anderson model

(Anderson 1961)

H ¼

X

k;s

e

k

c

þ

k;s

c

k;s

þ

X

i;s

E

0

f

þ

i;s

f

i;s

þ V

X

i;s

ðc

þ

i;s

f

i;s

þ c:c:ÞþU

X

i;s

n

m

f ;i

n

k

f ;i

ð1Þ

where n

s

f,i

¼f

þ

i,s

f

i,s

. It describes the conduction elec-

trons c

k,s

with dispersion e

k

and width W which hy-

bridize with the localized electrons of energy E

0

. The

hybridization matrix element is usually approximated

by a constant V. U represents the on-site Coulomb

repulsion between d( f ) electrons. For large Coulomb

repulsion U the d( f ) spectral weight is split into two

parts at E

f

and E

f

þU, having a width DEV

2

/W.

The Anderson model exhibits various parameter

regimes. (i) E

0

þUbE

F

, E

0

5E

F

with 7E

0

þUE

F

7,

7E

F

E

0

7bD. For such parameters local magnetic

moments exist which interact antiferromagnetically

with the conduction electrons. (ii) If E

0

or E

0

þU

approach the Fermi energy so that E

0

E

F

or

E

0

þUE

F

become comparable with D, or even

smaller, the charge fluctuations of the impurity be-

come important. This regime is known as the inter-

mediate valence regime. (iii) In the case of only small

admixtures of localized and delocalized electrons, the

Schrieffer–Wolff transformation allow transforma-

tion of the hybridization matrix element V of Eqn. (1)

into an effective exchange coupling J, equivalent to

the Heisenberg sd model, H ¼ J

~

s

~

S.

The Anderson Hamiltonian is then led over into

the Coqblin–Schrieffer model (Coqblin and Schrief-

fer 1969), which is used for practical reasons in most

of the theoretical treatments of Kondo physics. The

most powerful methods to diagonalize the Anderson,

and in particular the Coqblin–Schrieffer Hamiltonian

are the renormalization group calculations, the exact

Bethe-ansatz solution and the large-N approxima-

tion. Perturbation-type calculations and Fermi-liquid

theories are also used. An excellent review of these

subjects can be found in Hewson’s textbook (Hewson

1993) (see Electron Systems: Strong Correlations).

1.1 Transport Coefficients

In a general treatment of transport phenomena, the

linearized Boltzmann equation yields the following

373

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena

transport coefficients (Ziman 1964):

sR1=r ¼ e

2

K

0

ð2Þ

S ¼

K

1

7e7TK

0

ð3Þ

l ¼

1

T

K

2

K

2

1

K

0

ð4Þ

where s is the electrical conductivity, r is the elec-

trical resistivity, S the Seebeck coefficient and l the

thermal conductivity. In simple metallic systems,

the second term of Eqn. (4) is usually neglected.

The transport integrals K

n

are given by:

K

n

¼

k

3

F

3p

2

m

Z

e

n

k

tðe

k

Þ de

k

df

k

de

ð5Þ

where k

F

is the Fermi wave vector, m is the carrier

mass, e

k

is the carrier energy and f

k

is the Fermi–

Dirac distribution function.

The key magnitude of the transport integrals is

the relaxation time t(e

k

). Since conduction electrons

are scattered in and out of the d or f impurity orbitals,

the density of states (DOS) of such impurities, r

d(f)

(e),

determines the scattering rate. Formally, the energy-

and temperature-dependent scattering rate is given per

unit impurity concentration c

imp

by (Hewson 1993):

t

1

ðe

k

Þ¼2pc

imp

7V7

2

r

f ðdÞ

ðeÞð6Þ

Once t(e

k

) is known for particular interaction pro-

cesses, all the transport coefficients can be calculated.

1.2 Electrical Resistivity

(a) Single impurity Kondo systems

If 3d elements such as iron or manganese, or f elements

such as cerium, ytterbium or uranium, are dissolved in

a nonmagnetic host such as copper, aluminum or

LaAl

2

, spin-flip scattering occurs, responsible for the

generation of a spin-compensating cloud of conduc-

tion electrons around the impurity. As a result, the

impurity magnetic moment becomes screened, thus

forming a singlet ground state. In order to take

account of the removed spin and orbital degrees of

freedom, a narrow many-body resonance develops

close to the Fermi energy (Kondo resonance), which is

responsible for extraordinary low temperature features

of physical quantities. In particular, enhanced scatter-

ing of conduction electrons at low temperatures affects

transport coefficients, owing to an increased density of

low energy excitations in the Kondo resonance near

to E

F

, and the large DOS at E

F

owing to the Kondo

resonance is synonymous with extraordinarily en-

hanced effective masses of the carriers.

The first successful ansatz to account for the ob-

served anomalous behavior of such systems dates

back to Kondo (1964), who assumed that a local

magnetic moment with a spin

~

S is coupled via an

exchange interaction J with the conduction electron

spin

~

s, i.e., H ¼ J

~

s

~

S. Using a third-order perturba-

tion-type calculation in J leads to singular scattering

of the delocalized electrons near to E

F

and to a lnT

contribution to the electrical resistivity r(T), i.e.,

r

imp

¼ r

B

1 2JNðE

F

Þ ln

2g

p

D

k

B

T

ð7Þ

with

r

B

¼

pmc

imp

NðE

F

Þ

e

2

_

J

2

S ð S þ 1Þð8Þ

where 2g/p ¼1.13, D is a cut-off parameter and

N(E

F

) is the electronic density of states at the Fermi

energy E

F

.

For antiferromagnetic sd coupling, (Jo 0),

r

imp

(T) increases logarithmically with decreasing

temperature. However, since the ln T term diverges

for T-0, Kondo’s calculation becomes invalid at low

temperatures. If the leading-order logarithmic terms

are summed up, a divergence is obtained for Jo0ata

finite temperature T

K

, known as the Kondo temper-

ature (Hewson 1993). The electrical resistivity then

reads:

r

imp

¼ r

B

1

1 þ JNðE

F

Þ ln

2g

p

D

k

B

T

2

ð9Þ

and the characteristic temperature T

K

is given by

k

B

T

K

¼

2g

p

De

1=ð7J7NðE

F

ÞÞ

ð10Þ

The divergence of physical properties at T ¼T

K

is

unphysical since a supposed phase transition is sup-

pressed from very strong fluctuations. Besides, this

temperature marks the breakdown of the validity of

perturbation-type calculations as many-body inter-

actions become dominant.

Owing to the screening of magnetic moments by

the conduction electron spin density within a sphere

of radius xB(W/k

F

)T

K

, W y bandwidth, (Schlott-

mann 1989), magnetic scattering processes die out for

T5T

K

and the resulting singlet object acts entirely

like a simple potential scatterer. Hence, Fermi-liquid

(FL) results are applicable. In the scope of the

n-channel Kondo model (n ¼2S) r

imp

is expressed as

(Schlottmann and Sacraqmento 1993):

r

imp

¼ r

imp

ð0Þ 1 c

2

T

T

K

2

"#

with c

2

¼

1

8

5p

n þ 2

2

ð11Þ

374

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena

where n ¼2 represents the ordinary Kondo effect. A

model calculation for r

imp

over the full temperature

range requires knowledge of the density of states over

the low frequency range at all temperatures (Hewson

1993). By applying the noncrossing approximation

(NCA) to the Anderson model (Bickers et al. 1987),

resistivity results were derived for N ¼6(N ¼2j þ1).

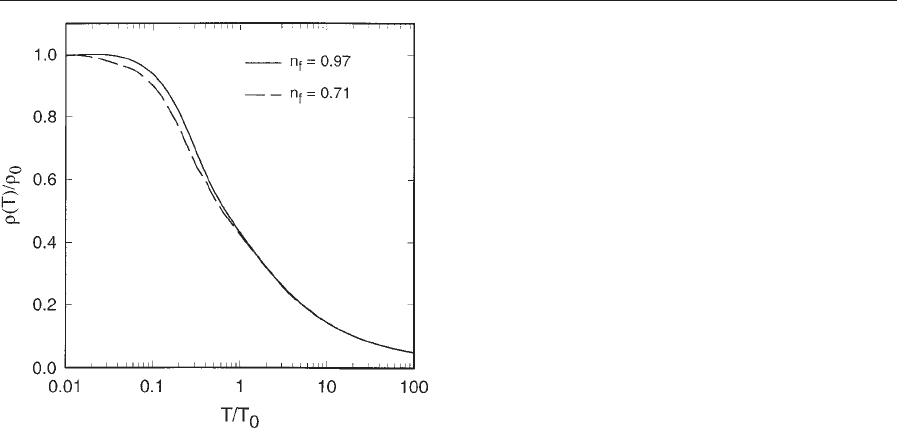

Results are shown in Fig. 1 for various values of the f

occupation number n

f

.

The NCA data exhibit an almost universal behavior

over a significant temperature range when plotted as a

function of T/T

0

, where T

0

¼wT

K

. w is Wilson

number (Hewson 1993) and T

0

can be associated

with the position of the Kondo resonance with respect

to the Fermi energy. Good overall agreement is found

from this model with experimental data of, for ex-

ample, cerium diluted in LaB

6

or FeCu (Schlottmann

and Sacramento 1993). The resistivity is roughly

logarithmic in T near T

0

; at low temperatures r(T)

saturates quadratically, in agreement with the Fermi-

liquid theory (Eqn. (11)). Based on an approximation

scheme (Fulde et al. 1993), a simple analytical expres-

sion is available for the transport coefficients, appli-

cable over an extended temperature range.

For N ¼2, corresponding to j ¼1/2 or to a doublet

as ground state, the NCA calculations can no longer

be used. Instead, Costi and Hewson (Hewson 1993)

adopted the numerical renormalization group meth-

od to account for the temperature dependence of the

dynamic response function, which allows derivation

of appropriate results for the resistivity, at least in the

crossover regime.

(b) Kondo impurity versus concentrated Kondo

systems

The above-outlined features primarily trace the tem-

perature dependence of the electrical resistivity of

impurity systems, that is, alloys where a statistically

small amount of 3d,4f or 5f elements are dissolved in

a nonmagnetic host such as gold, silver or copper.

Since in such a case the d or f wave-functions do not

overlap, the system will not order magnetically. In f

systems, however, it is possible to increase the

number of magnetic impurities up to a level where,

for example, cerium, ytterbium, or uranium build up

a fully ordered sublattice in the compound without

losing those appearances associated with the Kondo

effect. Basically, two features make a lattice different

from an impurity system: (i) intersite interactions be-

tween the magnetic moments on the various lattice

sites may no longer be negligible, and (ii) coherent

scattering of the conduction electrons with the perio-

dically arranged 4f and 5f magnetic moments is

responsible for dramatic change of r(T) on lowering

the temperature.

The definition of coherence corresponds simply to

Bloch’s theorem: at zero temperature and excita-

tion energy, inelastic scattering is frozen out so that

translational invariance of a perfect sublattice of the

magnetic ions requires zero resistance (Cox and

Grewe 1988). This coherent ground state of the 10

23

particles is most likely caused from the development

of antiferromagnetic correlations, as is proven from

neutron inelastic scattering, nuclear magnetic reso-

nance, and muon-spin relaxation (Thompson and

Lawrence 1994). While in the impurity case the re-

sistivity grows continuously, reaching the unitarity

limit for T-0 (associated with a phase shift Z ¼p/2),

coherence causes for a lattice of Kondo scatterers a

substantial decrease of r(T) upon a temperature

decrease and the occurrence of a maximum at

TET

0

pT

K

. In the low temperature limit, the fre-

quently observed power law r ¼r

0

þAT

2

evidences

electron-electron scattering in a FL state with

ApN(E

F

)

2

.

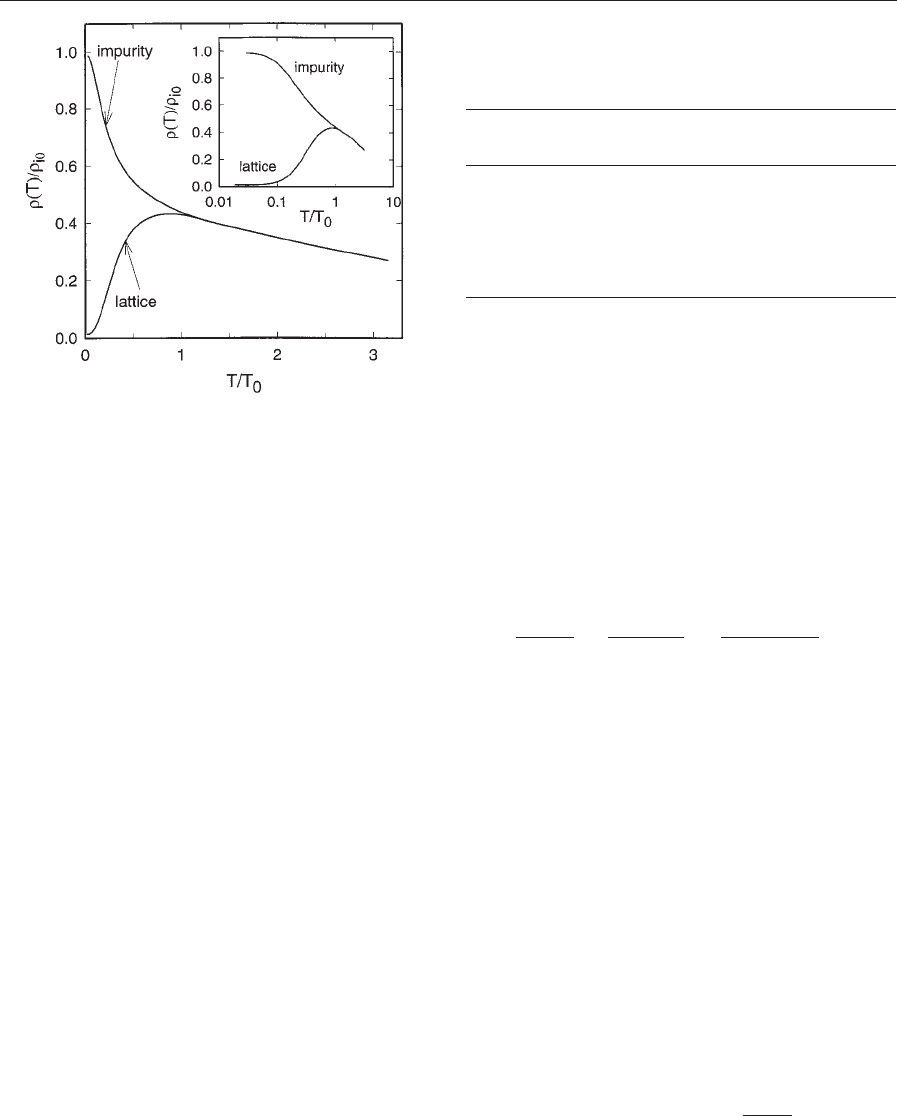

Cox and Grewe (1988) calculated the temperature-

dependent resistivity for both circumstances by ap-

plying the self-consistent NCA (Bickers et al. 1987)

to the periodic Anderson lattice, where they expli-

citly included coherence, but intersite interactions

are neglected. Results are shown in Fig. 2, match-

ing the expected features almost perfectly. If inter-

site interactions of the RKKY type gain weight

with respect to the Kondo interaction, the system

is able to order magnetically below a certain transi-

tion temperature T

mag

. Both the magnitude of the

ordered moments as well as T

mag

, however, can

significantly be reduced when compared to a sys-

tem without the Kondo effect. Such a transition

into a magnetically ordered ground state will

modify the low-temperature behavior of transport

coefficients.

Figure 1

Temperature variation of the scaled resistivity r(T)/r

0

calculated in the scope of the noncrossing

approximation for various values of n

f

.

375

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena

(c) Fermi- and non-Fermi-liquids

Although a large number of Kondo systems at low

temperature may be accounted for in terms of the

FL model, an increasing number of alloys and

compounds are already known, showing striking

deviations from the simple temperature dependencies

of an FL (see Non-Fermi Liquid Behavior: Quantum

Phase Transitions). This new class of materials was

termed non-Fermi-liquid (NFL). In most cases,

NFLs are characterized by a transition into an anti-

ferromagnetically ordered ground state at T ¼0,

which behaves as a quantum critical point (QCP).

Different scenarios were proposed to account for

the NFL behavior near to a QCP (Rosch 2000).

Among them are: (i) scattering of FL quasiparticles

by strong spin fluctuations near the spin-density-

wave instability, (ii) breakdown of the Kondo

effect, owing to competition with the RKKY inter-

action, and (iii) the formation of magnetic regions,

owing to rare configurations (Griffith phase) of the

disorder.

With respect to transport properties, the self-con-

sistent renormalization theory (SCR) of spin fluctu-

ations (Hatatani and Moriya 1995) was successfully

applied for ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic

heavy fermion systems around their magnetic insta-

bility. Depending on the nature of the interaction and

its dimensionality, the calculated resistivity clearly

deviates from the FL prediction rBT

2

. Some of the

results are listed in Table 1.

(d) Magnetoresistivity

The application of a magnetic field to Kondo systems

influences details of the DOS in the proximity of the

Fermi energy. Hence, properties depending on the

DOS are modified. The effect of a magnetic field

on the electrical resistivity is described by r(B)/r(0),

where r(B) and r(0) are the field and zero-field

resistivities, respectively.

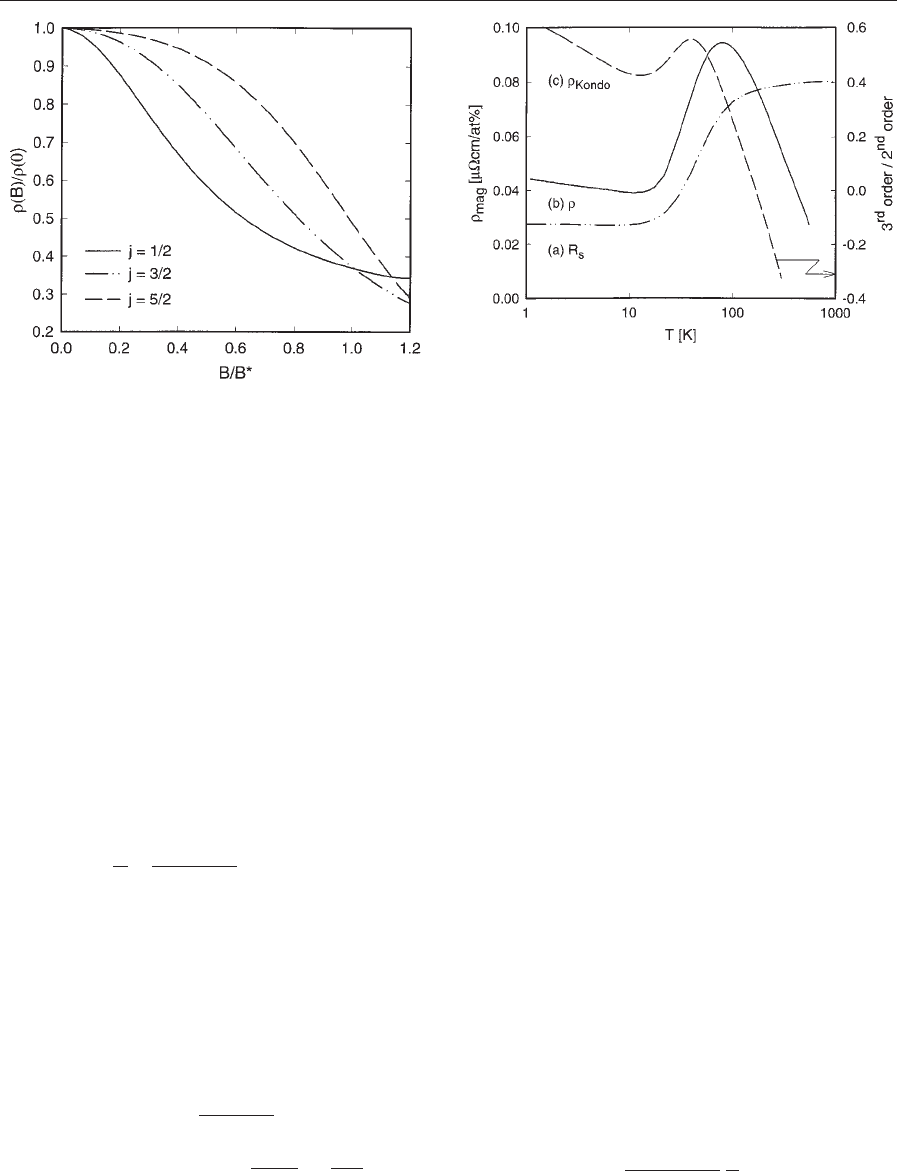

At T ¼0, the magnetoresistance can be derived

from the Friedel sum rule. In the scope of the

Coqblin–Schrieffer model (Coqblin and Schrieffer

1969) with N-fold degenerate total angular momen-

tum states, the Friedel sum rule yields:

r

imp

ðBÞ

r

imp

ð0Þ

¼

sin

2

ðp=NÞ

N

X

m

1

sin

2

ðpn

m

ðBÞÞ

"#

1

ð12Þ

where n

m

is the occupation number of the N ¼2j þ1

channels derived from Zeeman splitting. The occupa-

tion numbers can be calculated using the Bethe ansatz

solution (Schlottmann and Sacramento 1989). Results

of model calculations are shown in Fig. 3 for j-values

ranging from 1/2 to 5/2. The single impurity nature is

reflected from the scaling behavior of this quantity.

For large magnetic fields the magnetoresistivity

shows Kondo logarithms, which are characteristics of

asymptotic freedom and r

imp

(B) falls off as ln

2

(B/

T

K

). There are some qualitative differences of the

magnetoresistivity results for the different total an-

gular momenta, since for j ¼1/2 the Kondo peak is

on-resonance with the Fermi level but is above the

Fermi level for all other values of j. A magnetic field

causes, then, a decrease of the impurity density of

states for j ¼1/2 but an increase for jX3/2.

For N ¼2, the magnetoresistance can also be

expressed in terms of the impurity magnetization

(Hewson 1993):

r

imp

ðBÞ¼r

imp

ð0Þ cos

2

pM

imp

gm

B

ð13Þ

where M

imp

is the magnetization and g is the Lande

´

factor.

Figure 2

Normalized resistivity r(T)/r

i0

of the six-fold degenerate

Anderson lattice calculated in the scope of the

noncrossing approximation. For comparison, the full

temperature dependence of the impurity resistivity is

shown. r

i0

is the zero temperature resistivity per ion in

the dilute limit.

Table 1

Critical behavior of the electrical resistivity just at the

magnetic instability of two- and three-dimensional

ferro- and antiferromagnets.

Two-

dimensional

Three-

dimensional

Ferromagnetic

spin

fluctuations

r(T)BT

4/3

r(T)BT

5/3

Antiferromag-

netic spin

fluctuations

r(T)BT r(T)BT

3/2

376

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena

(e) Crystal field effects

In 4f systems based on cerium or ytterbium, crystal

field (CF) effects can no longer be neglected. The

thermal population of the various CF levels with in-

creasing temperature changes most of the physical

properties, and moreover, the Kondo effect itself

changes.

In the scope of a third-order perturbation-type

calculation in JN(E

F

), Cornut and Coqblin (1972)

derived the cumulative effect of Kondo interaction in

the presence of crystal field splitting. Results of their

calculations have been applied to numerous com-

pounds such as CeAl

2

or CeAl

3

. The relaxation time

t

k

for the above model is obtained as

1

t

k

¼

mkV

0

c

imp

p_

3

ð2j þ 1Þ

ðR

k

þ S

k

Þð14Þ

where k is the wave vector and V

0

the sample volume.

R

K

describes second-order terms (direct scattering

from the initial to the final state) and is proportional

to J

2

, while S

K

accounts for third-order terms (spin-

flip processes) which are proportional to J

3

. Direct

and resonant (Kondo) scattering yield the following

magnetic contribution to the electrical resistivity:

r

mag

ðTÞ¼ANðE

F

Þ

%

V

2

þ

l

2

n

1

l

n

ð2j þ 1Þ

J

2

þ ANðE

F

Þ J

3

NðE

F

Þ

l

2

n

1

2j þ 1

ln

k

B

T

D

n

ð15Þ

Here, A is a constant, V is the direct interaction

strength, and D

n

is a cut-off parameter. l

n

¼

P

n

i ¼0

a

i

,

where a

i

is the degeneracy of the ith CF level with

energy D

i

. The second term describes the usual

spin disorder resistivity (second-order perturbation

theory). The temperature dependence of this contri-

bution results from the thermal population of the

various CF levels. The third term is the Kondo resis-

tivity. The resistivity according to Eqn. (15) is plotted

in Fig. 4 for a typical set of parameters which roughly

accounts for the case of CeAl

2

.

1.3 Thermal Conductivity

In metallic systems, the thermal conductivity l con-

sists of a lattice contribution l

l

and of an electro-

nic contribution l

e

, i.e., l ¼l

l

þl

e

. According to

Matthiessens’s rule, the thermal resistivity W

l(e)

1/l

l(e)

is given by a sum resulting from different

scattering events, like electron–phonon scattering or

scattering of electrons or phonons on static imper-

fections. Thus, W

l(e)

¼S

i

W

l(e), i

. The temperature

dependence of l follows from Eqn. (4), using the

appropriate relaxation time. Thermal conductivity

limited by magnetic scattering processes in the pres-

ence of CF splitting is then derived from Eqn. (14) as

(Bhattacharjee and Coqblin 1988)

l

e;mag

ðTÞ¼

ð2j þ 1Þ_

3

k

2

F

3pm

2

v

0

c

1

T

ðW

2

W

3

Þð16Þ

Figure 3

Magnetoresistance r(B)/r(0) versus B/B* for the j ¼1/2

to j ¼5/2 Coqblin-Schrieffer model. B is the magnetic

field and B* is the characteristic field, closely related to

T

K

.

Figure 4

Temperature-dependent behavior of (a) the spin-

disorder resistivity R

s

, (b) the total resistivity r and

(c) the relative Kondo perturbation. The relevant

parameters are: cubic symmetry, D ¼100 K, D ¼400 K,

J ¼0.095 eV, V ¼0.07 eV,

V ¼0.05 eV, N(E

F

) ¼0.5

states/eV, a

1

¼2 and a

2

¼4.

377

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena

with

W

2

¼

Z

e

2

k

df

k

de

k

de

k

R

K

ð17Þ

and

W

3

¼

Z

e

2

k

df

k

de

k

S

K

R

2

K

de

k

ð18Þ

l

e,mag

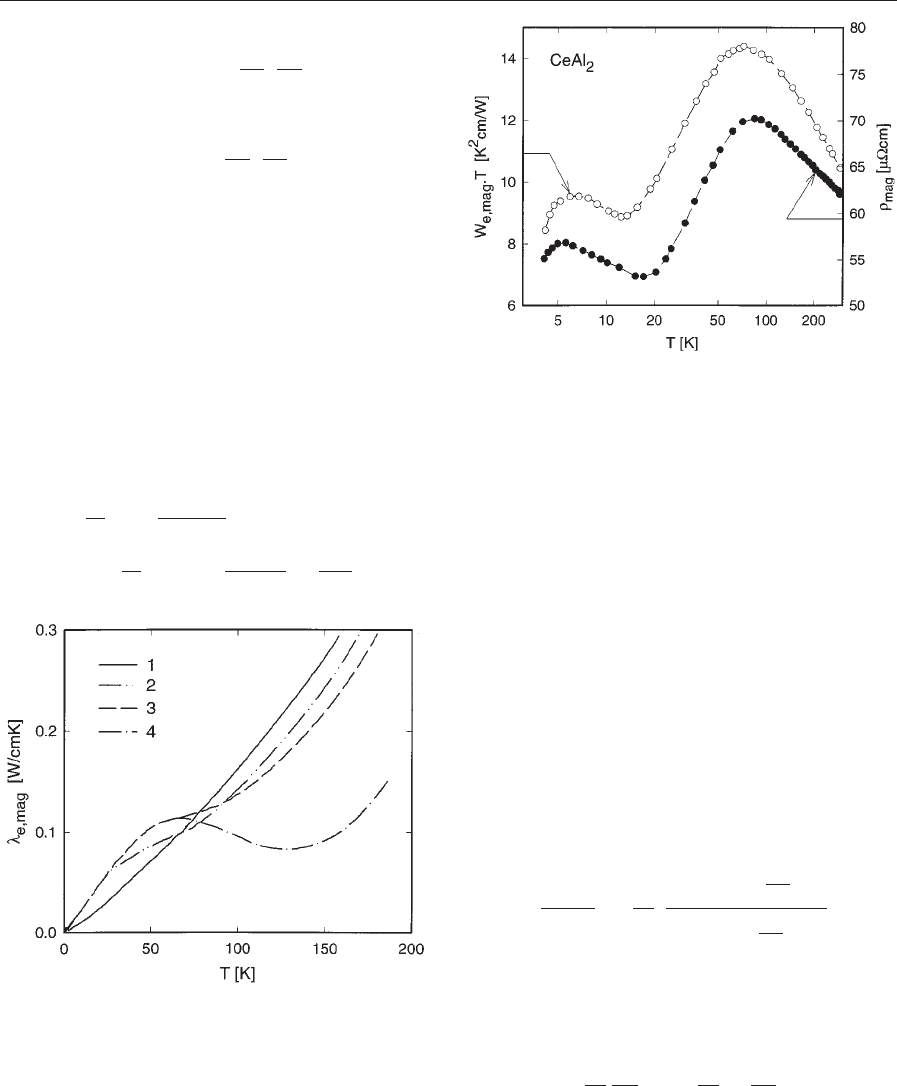

(T) is plotted in Fig. 5 for a set of typical pa-

rameters. It is interesting to note that there are no

typical features evidencing Kondo interaction; how-

ever, CF effects seem to be of importance.

Experimental data, however, clearly indicates

Kondo interaction in the presence of crystal field

splitting, when plotted as W

e,mag

T where W

e,mag

¼

1/l

e,mag

. Figure 6 shows W

e,mag

T of CeAl

2

displayed

on a logarithmic temperature scale. For purpose of

comparison, r

mag

(T) of CeAl

2

is added, also. Such a

representation of the data exhibits negative logarith-

mic ranges and a maximum, very similar to that of

r

mag

(T). This particular behavior can theoretically be

accounted for by (Bauer et al. 1993a)

W

e;mag

T ¼

R

L

0

%

V

2

þ

ðl

2

1Þ

ð2j þ 1Þl

J

2

þ 2

R

L

0

NðE

F

Þ J

3

ðl

2

1Þ

2j þ 1

ln

k

B

T

D

ð19Þ

where R ¼(3mpv

0

c)/(e

2

hk

2

F

), and L

0

¼(p

2

k

B

2

)/(3e

2

)is

the Sommerfeld value of the Lorenz number.

Equation (19) allows various conclusions to be

drawn. (i) There are negative logarithmic ranges for

W

e,mag

T at temperatures TbD

i

/k

B

and T5D

i

/k

B

. (ii)

W

e,mag

T shows maxima in the vicinity of each crystal

field level if they are well separated. (iii) The ratio of

the logarithmic slopes of W

e,mag

T reflects the degen-

eracy of the crystal field levels involved.

1.4 Thermopower

The temperature-dependent thermopower S(T ) can

be evaluated from

S ¼

K

1

7e7TK

0

¼

1

eT

Z

þN

N

e

k

t

k

df

k

de

de

k

Z

þN

N

t

k

df

k

de

de

k

2

6

6

6

4

3

7

7

7

5

ð20Þ

Owing to strong energy-dependent scattering proc-

esses, the Kondo effect sensitively influences the

overall shape of S(T), which is calculated from:

S ¼

1

eT

1

s

ð2Þ

Z

þN

N

S

k

R

2

k

df

k

de

k

de

k

ð21Þ

with e40 (Bhattacharjee and Coqblin 1976). R

k

and

S

k

are again contributions from the second and

third order perturbation type calculations; s

(2)

is a

Figure 5

Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity l

mag

caused by spin-dependent scattering according to Eqn.

(16): (1) cubic field with G

8

as ground state and

D ¼200 K; (2) hexagonal field with three equidistant

doublets at 0, 100 and 200 K; (3) cubic field with G

7

as

ground state and D ¼200 K. (4) hexagonal field with

three doublets at 0, 200 and 400 K. Additional

parameters are D ¼850 K, V ¼700 K, J ¼0.1 eV,

V ¼0.25 eV, N(E

F

) ¼2 states/eV.

Figure 6

Left axis: temperature-dependent magnetic contribution

to the thermal resistivity of CeAl

2

, plotted as W

e,mag

T

versus lnT. Right axis: temperature-dependent magnetic

contribution to the electrical resistivity r

mag

of CeAl

2

.

LaAl

2

was used in both cases to define the electron–

phonon interaction.

378

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena

characteristic function:

s

ð2Þ

¼

Z

þN

N

1

R

2

k

df

k

de

k

de

k

ð22Þ

In the absence of CF splitting, Kondo scattering is

responsible for unusually large thermopower values

(E100 mVK

1

) with a maximum in the vicinity of

TET

K

. In real compounds and alloys, CF effects

cause a modification of that universal behavior. The

maximum in S(T) is then no longer at TET

K

, rather,

a renormalization of T

max

S

takes place with T

max

S

E

(1/31/6)D

CF

, where D

CF

is the overall crystal field

splitting of the system. Results derived from Eqn.

(21) are shown in Fig. 7.

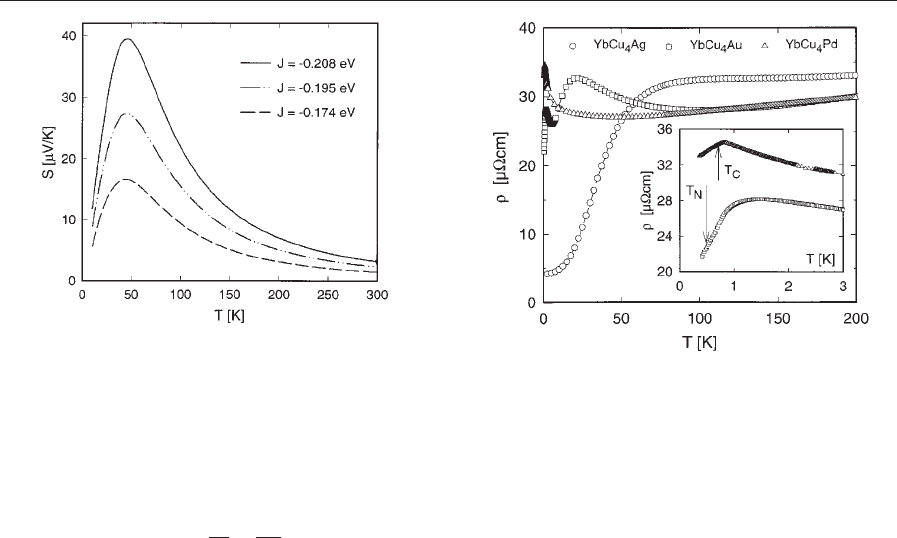

2. Temperature-, Pressure-, and Field-dependent

Transport Coefficients of Kondo and Heavy

Fermion Sys tems

In order to demonstrate the various interaction

mechanisms which generally occur in Kondo and

heavy fermion systems, as well as their mutual inter-

play, the temperature-dependent resistivity of

YbCu

4

M, with M ¼Ag, Au and Pd, is shown in

Fig. 8 (Bauer et al. 1993b, 1994). The compounds are

isoelectronic and isostructural and crystallize in an

ordered variant of the cubic AuBe

5

structure. Differ-

ent dominating interaction mechanisms cause distinct

features for each particular compound.

2.1 YbCu

4

Ag

This crystallographic fully ordered ternary com-

pound represents a typical Kondo lattice. At high

temperatures, the negative logarithmic contribution

to the total electrical resistivity leads to single impu-

rity Kondo interaction of the conduction electrons

with the almost localized Yb-4f moments. At low

temperatures, however, the ordered ytterbium sub-

lattice allows a Bloch-like motion of the conduction

electrons, and consequently the resistivity falls. Both

regimes are separated by a smooth maximum near

100 K with T

max

r

pT

K

(Cox and Grewe 1988). There-

fore, YbCu

4

Ag represents a Kondo lattice with a

relatively high Kondo temperature.

This provokes a couple of important consequences

for physical properties: because T

K

of YbCu

4

Ag is

large, the associated hybridization prevents pro-

nounced CF effects and the eight-fold degenerate

state of the Yb ion (j ¼7/2) dominates the whole

temperature range. Moreover, as T

K

bT

RKKY

, long-

range magnetic order is unlikely and the system re-

mains paramagnetic down to the mK range. Below

10 K the T

2

behavior of r(T) refers to a FL behavior

and the large coefficient A ¼8nO cm/K

2

(Bauer et al.

1993b) results from interactions with the heavy quasi-

particle bands. The overall r(T) behavior matches

almost perfectly the theoretical predictions of Cox

and Grewe (1988).

2.2 YbCu

4

Au

Although YbCu

4

Au is isoelectronic with YbCu

4

Ag,

the ground state properties behave significantly dif-

ferently. While the latter is nonmagnetic, the former

orders antiferromagnetically below T

N

E0.6 K (see

inset, Fig. 8) with a wave vector

~

k ¼[0.553, 0.415,

0.303] and an ordered moment m ¼0.85 m

B

/Yb (Bauer

et al. 1997). A comparison with YbCu

4

Ag shows that

primarily the low value of the Kondo temperature

Figure 7

Temperature-dependent thermopower for a three-level

system according to Eqn. (21) for various values of the

exchange constant J. The following parameters are used:

D

1

¼87 K, D

2

¼210 K, D ¼850 K,

V ¼1.5 eV,

N(E

F

) ¼2.2 states/eV, a

1

¼a

2

¼a

3

¼2.

Figure 8

Temperature-dependent resistivity r of YbCu

4

M with

M ¼Au, Ag, Pd.

379

Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Transport Phenomena