Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

crystallographic c axis) it is strongly reduced. The

corresponding resistivity values are referred to as

r

ab

and r

c

, respectively. Near room temperature for

a typical cuprate such as YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

we have

the values r

ab

¼200–500 mOcm, compared to r ¼2–

5 mOcm for a typical metal. The ratio r

c

/r

ab

of the

anisotropy near room temperature ranges from 30–60

for YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

up to 1 10

5

for Bi

2

Sr

2

CaCu

2

O

8

.

The fact, that near room temperature r

ab

is about 100

times larger than the resistivity in a typical metal, is

partly due to the lower charge carrier concentration

and the pronounced anisotropy in the cuprate.

Above the critical temperature T

c

near optimum

doping the normal-state resistivity of many cuprate

superconductors increases linearly with temperature.

A prominent exception is the electron-doped cuprate

Nd

2x

Ce

x

CuO

y

showing r

ab

BT

2

near optimum dop-

ing. This normal-state resistive behavior can be qual-

itatively explained in terms of the nature of the

scattering processes and the electronic density of

states (DOS). It is now well established that in the

cuprates the electron scattering processes are domi-

nated by the electron–electron interaction, in contrast

to electron–phonon scattering prevailing in metals.

An important piece of evidence for this scattering

behavior comes from the pronounced increase of the

electron mean free path with decreasing temperature

below T

c

as soon as the quasi-particles (as scattering

partners) are frozen out because of the opening of the

energy gap. With decreasing temperature this also

leads to a sharp upwards turn of the thermal con-

ductivity k(T)atT

c

. The thermal conductivity then

passes through a maximum near T

c

/2. If the electron–

phonon interaction would dominate, such an abrupt

change of the temperature dependence of the electron

mean free path at T

c

would not be expected.

The r

ab

BT

2

behavior observed near optimum

doping in Nd

2x

Ce

x

CuO

y

is well consistent with the

electron–electron interaction as the dominant scat-

tering mechanism. On the other hand, the linear tem-

perature dependence r

ab

BT found usually in the

optimally hole-doped cuprates can be qualitatively

explained by a sharp peak (Van Hove singularity) in

the electronic DOS near the Fermi energy E

F

. The

additional phase space for scattering within this peak

region then leads to the proportionality for the scat-

tering rate t

1

Bk

B

T (marginal Fermi liquid), instead

of the usual Fermi liquid behavior t

1

B(k

B

T )

2

.

Here, k

B

is Boltzmann’s constant (Newns et al. 1993).

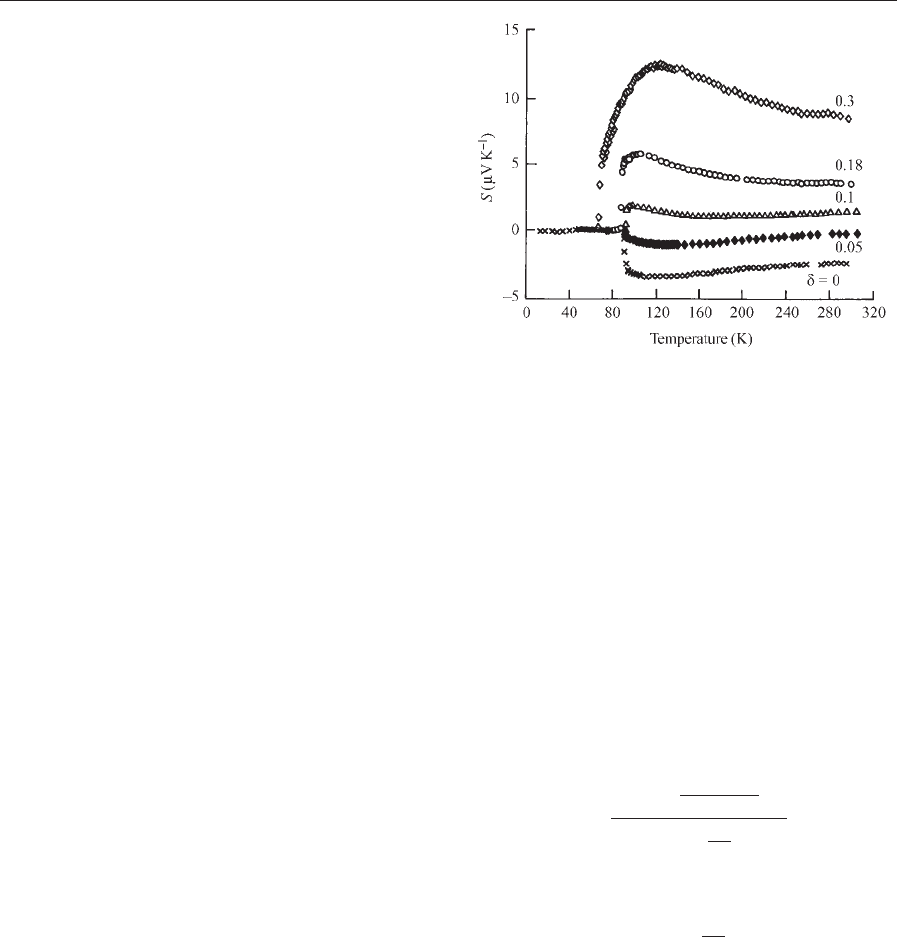

The normal-state thermopower (Seebeck coeffi-

cient) represents a transport property depending

highly sensitively on the electronic structure and the

doping level of the cuprates. There exists an interest-

ing correlation between the thermopower and the

critical temperature T

c

. Depending on the doping

level, the thermopower at room temperature of dif-

ferent p doped systems follows a universal curve tra-

versing zero at optimum doping (corresponding to

the maximum value of T

c

). The typical temperature

dependence of the thermopower shows an increase of

its absolute value above T

c

, turning into a flat curve

with falling tendency at higher temperatures. This

behavior is strongly different from the proportion-

ality to T expected in the limit of a wide (bk

B

T)

conduction band. A typical series of curves is shown

in Fig. 1 for YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

at different levels d of

oxygen depletion (Cooper et al. 1991).

This dependence of the thermopower on the tem-

perature and the doping level can be understood from

standard transport theory in combination with the

sharp peak in the electronic DOS near the Fermi

level. For the (positive) holes the thermopower is

S ¼

k

B

7e7

Z

s

E

@f

@E

E E

F

k

B

T

dE

Z

s

E

@f

@E

dE

ð1Þ

with the electric conductivity given by

s ¼

Z

s

E

@f

@E

dE ð2Þ

(Kubo–Greenwood formula). Here f is the Fermi

function, and s

E

contains the density of states and the

scattering processes. We emphasize that, because of

the sharp peak in the electronic DOS near E

F

, the

derivative @f/@E changes only little in the relevant

energy interval. From Eqn. (1) we can predict the

following qualitative behavior.

If E

F

is smaller (larger) than the energy of the DOS

peak, the contribution with EE

F

40(o0) domi-

nates and the thermopower will be positive (nega-

tive). Hence, the sign reversal of the thermopower is

Figure 1

Thermopower S of the cuprate YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

versus

temperature for different values d of the oxygen

depletion (after Cooper et al. 1991).

310

High-temperature Superconductors: Transport Phenomena

expected, when the Fermi energy coincides with the

energy of the DOS peak. Alternatively, according to

the ‘‘Van Hove scenario’’ of high-temperature super-

conductivity this location of the Fermi level corre-

sponds exactly to the optimum doping level yielding

the maximum value of T

c

. The experiments per-

formed with different p doped cuprate systems at

varying doping levels mentioned above well con-

firmed these ideas (Newns et al. 1993).

In the orthorhombic form of the cuprate

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

one of the copper oxide planes per el-

ementary cell contains CuO chains along the b axis,

but not along the a axis. This introduces some an-

isotropy of the transport properties even within the

ab planes, in addition to the large anisotropy between

the ab plane and the c direction.

The normal state Hall effect represents a compli-

cated subject. However, it is this effect that led to

the concepts of ‘‘hole-doped’’ and ‘‘electron-doped’’

cuprate superconductors. The Hall coefficient R

H

¼

1/nq yields information on the nature of the charge

carriers involved in the electronic transport. Here n

and q are the concentration and elementary charge of

the charge carriers, respectively. For hole-doped con-

ductors R

H

is positive, whereas for electron-doped

materials it is negative. For the magnetic field orien-

tation in c direction in most of the high-temperature

superconductors R

H

is positive, indicating hole dop-

ing. Compounds derived from Nd

2

CuO

4

by substitu-

tional alloying (Nd

2x

Ce

x

CuO

y

) are the major

exception and show electron doping. In the latter

case of Nd

2x

Ce

x

CuO

y

an additional complication

arises from the fact that a two-band model appears to

be necessary, with an electron-like and a hole-like

section, for describing the electronic properties.

An unexpected result of the Hall effect measure-

ments is the observed strong temperature dependence

of the Hall coefficient, especially near optimum dop-

ing. Such a temperature dependence does not arise in

a canonical Fermi liquid. In YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

, the most

intensively studied cuprate superconductor, for the

inverse Hall coefficient the relation R

1

H

¼a þbT has

been found, where a and b are constants. An inter-

esting quantity is the Hall angle, y

H

, the angle

between the electric current density and the total

electric field, which is given by tany

H

¼R

H

B/r. From

electronic transport theory, one finds that tany

H

is

equal to /o

c

tS, a weighted average for the dominant

conducting particles of the product of their cyclo-

tron frequency o

c

¼qB/m* for the electron orbits

in the magnetic field and their scattering time t (m* ¼

effective mass).

Hence, coty

H

is expected to be proportional to the

scattering rate t

1

. In YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

across the whole

of the metallic doping range the relation co-

ty

H

¼a þbT

2

is valid in good approximation, again,

a and b being constants. We conclude that the scat-

tering rate also shows this a þbT

2

temperature de-

pendence. Noting R

1

H

Bn and rB(nt)

1

, we see that

the linear temperature dependence of R

1

H

and the

(a þbT

2

) behavior of the scattering rate appear con-

sistent with the linear temperature dependence of the

resistance observed in many cuprates discussed

above. We emphasize that we must restrict our dis-

cussion to rough and qualitative remarks only, leav-

ing out many details of the electronic structure of

these materials.

2. Granular Structure

Except for the highly specialized procedures for ma-

terial fabrication developed for the growth of axis-

oriented epitaxial films and single crystals, the high-

temperature superconductors are usually prepared as

ceramics with a granular structure. Within the grain

boundary regions superconductivity is strongly weak-

ened or even totally absent. Hence, the grain bound-

aries in the cuprate superconductors have to date

presented a challenging technological problem. It still

is an important goal of the present technological de-

velopments to minimize the residual electric resist-

ance due to the grain boundaries as much as possible.

Recently, special doping processes for the grain

boundaries in order to improve the electric conduc-

tivity in these regions have been discussed. The im-

portant quantity to deal with is the critical current

density at which a specific nonzero electric field is

generated in the superconductor, resulting in power

dissipation. The current flow pattern in a multigran-

ular superconductor has been treated in analogy to

the structure of a brick wall (brick wall model). In

addition to the granular structure, the poor ductility

of the cuprate superconductors continues to represent

a severe obstacle, in particular for the technological

power applications.

For the applications of high-temperature super-

conductors in microelectronics the critical current

density in thin films has received a large amount

of attention. Here c axis oriented epitaxial films of

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

clearly represent the work horse. At

77 K and in zero magnetic field, critical current den-

sities of 1 10

6

–1 10

7

Acm

2

have been achieved, a

highly impressive result of the associated materials

science.

Whereas the grain boundaries in the cuprate su-

perconductors are clearly detrimental to many tech-

nical applications, in one specific case they turned out

to be extremely useful and they represent a well con-

trollable and stable Josephson junction. The grain

boundary Josephson junctions are fabricated by

growing an epitaxial superconducting cuprate film

on a bicrystal acting as the substrate. The grain

boundary separating the two single-crystalline pieces

of the substrate is then transferred to the epitaxial film

deposited subsequently on the bicrystalline substrate.

In this way, during recent years Josephson devices and

superconducting quantum interferometers (SQUIDs)

311

High-temperature Superconductors: Transport Phenomena

operating up to 77 K have been fabricated (see

Josephson Junctions: High-T

c

).

3. Current-induced Vortex Motion

In a magnetic field in the range between the lower and

upper critical field, B

c1

and B

c2

, respectively, below

the critical temperature T

c

the superconducting

mixed state is established. In the mixed state the su-

perconductor is penetrated by a more or less perfectly

ordered 2D lattice of flux lines, each flux line carrying

a single magnetic flux quantum j

0

. The regularity of

this lattice depends on the spatial homogeneity of the

superconductor. The following will be restricted to

the case where the magnetic field and, hence, the flux

lines, are oriented along the crystallographic c axis. In

this case the flux lines degenerate into stacks of pan-

cake vortices (or point vortices) attached to the CuO

2

planes constituting the superconducting structural el-

ements of the cuprates. Under the influence of an

external force the flux lines or pancake vortices can

be set into motion. This vortex motion represents one

of the most important processes in superconductors,

since it results in an electric field of quantum me-

chanical origin and thereby destroys superconductiv-

ity (Huebener 2001).

An electric transport current of density

j generates

the Lorentz force

j j

0

per unit length of flux line.

The dynamic state of the vortex lattice is determined

by the force equation:

j j

0

Zv

j

aðv

j

nÞþf

p

¼ 0 ð3Þ

The Lorentz force is balanced by the damping force

Z

v

j

, the Hall force aðv

j

nÞ, and the pinning force

f

p

v

j

is the vortex velocity, Z and a are damping

coefficients,

n is a unit vector in magnetic field direc-

tion. Vortex motion always results in an electric field

E according to the equation:

E ¼v

j

B ð4Þ

Equation (4) is derived from the phase change of

the macroscopic wave function describing the Cooper

pair condensate, effected by the vortex motion. (It is

intimately connected with the Josephson voltage fre-

quency relation.) In the absence of the Hall force and

the pinning force we see from Eqns. (3) and (4) that

n

j

is perpendicular to j and, therefore, E is parallel to

j. As a result power dissipation E j per unit volume

occurs, and superconductivity is destroyed. It is this

mechanism of current induced vortex motion and the

appearance of flux-flow resistance which represent

the main challenge to maintaining superconductivity.

Because of the three characteristic novel features of

the high-temperature superconductors (high critical

temperature, small coherence length, and large an-

isotropy) vortex motion and the appearance of flux-

flow resistance is highly facilitated in the cuprates and

turns out to be an even more challenging issue than in

the classical superconductors.

It is the pinning force in Eqn. (3) which can result

in a strong reduction of vortex motion and, hence,

contributes to sustaining superconductivity at finite

electric transport current. Flux pinning is accom-

plished by material inhomogeneities (pinning centers)

causing a local depression of the Gibbs free energy

density of the vortex lattice. Because of the short co-

herence length in the cuprates, atomic size defects,

such as oxygen vacancies in the CuO

2

planes or de-

fects produced by substitutional alloying, already act

as important pinning centers. The pinning force even-

tually acting on the vortex lattice results from the

combination of the elementary pinning interaction

between a vortex and the pinning center with the

elastic properties of the vortex lattice. The elastic

properties come in, since the vortex lattice must be

deformed in order to accommodate the spatial con-

figuration of the pinning sites. Because of this, flux

pinning turns out to be a highly complex phenome-

non. However, because of its extreme importance for

the technical applications of the cuprate supercon-

ductors, the subject of flux pinning has recently at-

tracted a large amount of research and development.

If the damping force Z

n

j

and the pinning force

would be absent in Eqn. (3), the vortices would move

parallel to the current density

j, the electric field E

would be perpendicular to

j (pure Hall electric field),

and the power dissipation

j E would vanish. How-

ever, for this to happen the quasi-particle scattering

time t must approach the limit t-N.

According to the Bardeen–Stephen model, valid

for the classical superconductors and serving, at best,

as a qualitative orientation for the high-temperature

superconductors, the flux-flow resistivity r

f

is given

by

r

f

¼ r

n

B

B

c2

where r

n

is the normal-state resistivity. In this model

the vortex core is taken as a normal-state cylinder of

radius x. The ratio B/B

c2

then represents the volume

fraction of this normal phase. For the damping co-

efficient Z one finds Z ¼j

0

B

c2

/r

n

. In the current-in-

duced flux-flow state the Hall angle y

H

is given by tan

y

H

¼o

c

t, similar to the situation in the normal

state. In the superconducting mixed state of the

cuprates the Hall angle is generally small (typically

tan y

H

E1 10

2

), and dissipative vortex motion

perpendicular to the electric current direction

dominates.

In contrast to the classical superconductors, in the

cuprate superconductors the description of the vortex

core as a normal-state cylinder of radius x is only a

rough approximation. Here also the symmetry of the

pair wave function must be discussed. It is now well

established that in the p-doped cuprates the pair wave

312

High-temperature Superconductors: Transport Phenomena

function shows d-wave symmetry, with four node

lines where the gap energy reaches zero. This has im-

portant consequences for the quasi-particle scattering

in the mixed state. However, at present the experi-

mental and theoretical clarification of this point is

still in progress. Another new aspect of quasi-particle

scattering originates from the extremely short coher-

ence length and the corresponding small vortex-core

diameter in the cuprates. As a result, quantum effects

of the electronic structure of the vortex cores (quan-

tum confinement) can become important. The de-

scription of the vortex core as a normal-state cylinder

of radius x is then highly inadequate. At least in the

limit T5T

c

this can lead to a strong reduction of the

phase space available for quasi-particle scattering.

Again, at present this issue is still under experimental

and theoretical investigation (Huebener 2001).

The peculiar features of the high-temperature

superconductors (high critical temperature, short

coherence length, and anisotropy leading to the pan-

cake-vortex structure) have important consequences

for the dynamic properties of the vortex lattice. There

exists an irreversibility line in the phase space of

magnetic field and temperature, above which the

magnetization is perfectly reversible with no detect-

able flux pinning. Alternatively, below this line the

magnetization becomes hysteretic, and the equilibri-

um vortex distribution cannot be established any

more because of flux pinning. From these observa-

tions in the 1990s the new concept of ‘‘vortex matter’’

evolved, with a liquid, glassy, and crystalline state,

displaying a complex phase diagram. These novel

features strongly influence the transport processes

associated with vortex motion.

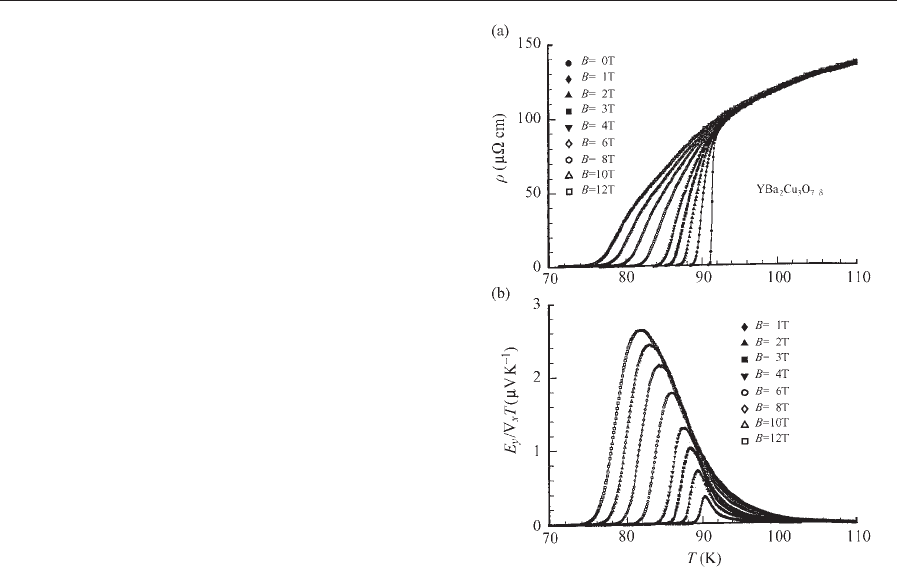

An immediate result of the different phases of vor-

tex matter appearing in the mixed state is the broad-

ening of the resistive transition in a magnetic field.

Whereas in the classical superconductors the drop in

the electric resistivity due to the onset of supercon-

ductivity is usually shifted to lower temperatures with

increasing magnetic field, in high-temperature super-

conductors the resistively measured onset tempera-

ture of superconductivity is only weakly magnetic

field dependent, but the transition curve is broadened

instead, and the broadening increases strongly with

increasing magnetic field. A typical case is shown in

Fig. 2a for an epitaxial c axis oriented YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

film for magnetic fields ranging from 0 to 12 T and

oriented in c direction. An exception from this broad-

ening of the resistive transition in a magnetic field has

been observed for the electron-doped cuprate super-

conductor Nd

2x

Ce

x

CuO

47y

in the whole doping re-

gime from slightly underdoped to slightly overdoped.

Here the whole resistive transition curve is shifted to

lower temperatures with increasing magnetic field,

more like in classical superconductors.

The motion of the vortex lattice due to the Lorentz

force of an electric transport current is accompa-

nied by the transport of entropy carried by the vortex

lattice. This entropy transport causes a temperature

gradient perpendicular to the directions of the electric

current and magnetic field. It is referred to as the

Ettinghausen effect and has been observed in a

number of high-temperature superconductors. If the

electric current density j

x

is assumed in x direction

and the magnetic flux density B

z

in z direction, the

heat current density U

y

in y direction associated with

the entropy transport is

U

y

¼ eB

z

kj

x

ð5Þ

Here e is the Ettinghausen coefficient and k the heat

conductivity. The Ettinghausen effect represents one

of the major observations supporting the concept of

vortex motion as the mechanism generating the elec-

tric resistance in the superconducting mixed state.

The experiments on the flux-flow Hall effect in the

cuprate superconductors indicated an unexpected re-

versal of the sign of the Hall voltage at temperatures

below the superconducting transition. This effect has

been observed in different materials and appears to

Figure 2

(a) Flux-flow resistivity of the cuprate superconductor

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

versus temperature for different magnetic

fields oriented in c direction. (b) Normalized Nernst

electric field E

y

/r

x

T versus temperature for the same

sample and magnetic fields as in (a).

313

High-temperature Superconductors: Transport Phenomena

represent an intrinsic property. A satisfactory theo-

retical understanding of this effect has not yet been

reached, and the theoretical discussions are still con-

troversial.

4. Vortex Moti on in a Temperature Gradient

In a temperature gradient applied to a superconduc-

tor in the mixed state the thermal force S

j

gradT

acts on the vortex structure, driving the magnetic flux

quanta from the hot to the cold side of the specimen.

Here S

j

is the transport entropy per unit length of

flux line. The thermal force is the driving force in all

thermal diffusion phenomena, and the transport en-

tropy represents a characteristic property of the spe-

cific type of particle under consideration. (The heat

current density U carried by a flux-line lattice moving

with velocity

v

j

is U ¼nTS

j

v

j

, where n ¼B/j

0

is the

density of flux lines.) For treating the dynamic state

of the vortex lattice driven by a temperature gradient,

in Eqn. (3) the Lorentz force

j j

0

must be replaced

by the thermal force S

j

gradT. If we neglect the Hall

effect and flux pinning, take the temperature gradient

in x direction and the magnetic field in z direction, we

see from Eqn. (4) that the resulting flux-flow electric

field is oriented in y direction. This electric field E

y

is

given by

E

y

¼ nB

z

@T

@x

ð6Þ

and the effect is referred to as the Nernst effect. n is

the Nernst coefficient. The Ettinghausen coefficient e

and the Nernst coefficient n are coupled through the

Bridgman relation of irreversible thermodynamics

Tn ¼ ek ð7Þ

The Nernst effect has been investigated in the mixed

state of a number of high-temperature superconduc-

tors. In Fig. 2(b) we show typical results obtained for

the same epitaxial YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

film and the same

magnetic fields as in Fig. 2(a). In the normal state

sufficiently far above T

c

(of about 91 K in this case)

the Nernst electric field E

y

is seen to be negligible.

With decreasing temperature E

y

increases and passes

through a maximum. As one expects because of the

flux-flow process, E

y

increases with increasing flux

density B. On the low-temperature end of the curves

the Nernst electric field E

y

and the resistivity vanish

because of flux pinning. From Fig. 2(b) we see also,

that the flux-flow Nernst effect clearly extends to

temperatures well above the critical temperature T

c

measured at zero magnetic field.

This is due to fluctuation effects, which become

stronger with increasing magnetic field. These fluctu-

ation effects can be measured with high accuracy,

since the Nernst effect is negligible in the normal state,

and a special subtraction procedure is not necessary.

Because of the small coherence length, high critical

temperature, and large anisotropy in the cuprate, su-

perconductor fluctuations play a much more promi-

nent role than in the classical superconductors. Hence,

this subject has received much experimental and the-

oretical attention.

In thermal diffusion experiments the high sensiti-

vity of the properties of a superconductor to the

temperature represents an important point, and

the application of a large temperature gradient to

the sample often causes complications. However, an

interesting exception is a geometry, where the sample

dimension in the direction of the temperature gradi-

ent is kept small, e.g., about 100 mm. In this case a

large temperature gradient can be achieved even for a

small temperature difference between the hot and the

cold side of the sample.

In our discussion of the thermal diffusion of mag-

netic flux quanta we have neglected the Hall force

að

n

j

nÞ. However, if we include the latter force, a

finite Hall angle of the resulting vortex velocity

n

j

appears, generating a component n

jy

perpendicular

to the direction of the temperature gradient. This ve-

locity component n

jy

produces a longitudinal electric

field component E

x

, i.e., a contribution to the See-

beck effect. Furthermore, in the superconducting

mixed state the responses of the quasi-particles to the

applied temperature gradient also must be discussed,

in addition to that of the magnetic flux quanta.

However, this subject is beyond the scope of this ar-

ticle, and we refer to the treatments by Huebener

(1995, 2001).

5. Concluding Remarks

Since their discovery in 1986 the cuprate supercon-

ductors have attracted a large amount of research

and engineering developments worldwide. One of the

main reasons for this strong interest has been the fact

that in many cuprates the critical temperature of su-

perconductivity is well above the boiling point of

liquid nitrogen. The layered crystallographic struc-

ture of these materials with the CuO

2

planes repre-

sents the most prominent characteristic feature

dominating the electronic properties. The undoped

cuprate perovskites are antiferromagnetic electric in-

sulators and become electric conductors and super-

conductors only by doping. Most high-temperature

superconductors are p doped, but n doping also leads

to superconductivity in some cases. While supercon-

ductivity is based on Cooper pairs as in the classical

superconductors, the pairing mechanism still remains

unclear.

It is now well established that in the hole-doped

cuprates the pair wave function shows d-wave sym-

metry, whereas the symmetry is not yet as clearly

known in the electron-doped cuprates. In many ways

the normal-state electronic transport properties do

314

High-temperature Superconductors: Transport Phenomena

not show the canonical Fermi liquid behavior well

known for metallic conductors. However, these prop-

erties of the normal state continue to provide clues

regarding the superconducting pairing mechanism.

The critical temperature value of many high-temper-

ature superconductors above the boiling point of liq-

uid nitrogen clearly represents an important asset for

practical applications. However, the granular struc-

ture and poor ductility still provides a challenge for a

technology based on these materials.

See also: Electrodynamics of Superconductors: Flux

Properties; Superconducting Thin Films: Multilayers;

High-temperature Superconductors: Thin Films and

Multilayers

Bibliography

Bednorz J G, Mu

¨

ller K A 1988 Perovskite-type oxides—the new

approach to high-T

c

superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 60,

585–600

Cooper J R, Obertelli S D, Carrington A, Loram J W 1991

Effect of oxygen depletion on the transport properties of

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

. Phys. Rev. B. 44, 12086–9

Huebener R P 1995 Superconductors in a temperature gradient.

Supercond. Sci. Technol. 8, 189–98

Huebener R P 2001 Magnetic Flux Structures in Superconduc-

tors. 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin

Levin K, Kim Ju H, Lu J P, Si Quimiao 1991 Normal state

properties in the cuprates and their Fermi liquid based in-

terpretation. Physica C 175, 449–522

Newns D M, Krishnamurthy H R, Pattnaik P C, Tsuei C C,

Chi C C, Kane C L 1993 Van Hove scenario for cuprate

superconductivity. Physica B 186–8, 801–7

Pickett W E 1989 Electronic structure of the high-temperature

oxide superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 61, 433–512

Poole C P, Farach H A, Creswick R J 1995 Superconductivity.

Academic Press, San Diego, CA

Tinkham M 1996 Introduction to Superconductivity, 2nd edn.

McGraw-Hill, New York

Waldram J R 1996 Superconductivity of Metals and Cuprates.

Institute of Physics, Bristol, UK

R. P. Huebener

University of Tu

¨

bingen, Germany

315

High-temperature Superconductors: Transport Phenomena

This page intentionally left blank

316

Intermediate Valence Systems

The group of rare-earth elements comprise the series

from lanthanum (atomic number 57) to lutetium

(atomic number 71), where the electronic configura-

tion (EC) gradually changes from [Xe]4f

0

5d

1

6s

2

to

[Xe]4f

14

5d

1

6s

2

, respectively (see Localized 4f and 5f

Moments: Magnetism). Light elements of this series

like cerium, elements with a nearly half-filled 4f shell

like samarium and europium, or with an almost filled

4f shell like thulium and ytterbium may, however,

deviate from such a well-defined EC with integer

valency. As a result, the ions exhibit intermediate

valence (IV), representing a homogeneous quantum

mechanical mixture of two consecutive integer va-

lence configurations. Not only are rare-earth systems

known to show such valence instabilities, but about

40 elements (3d,4d,5d,5f ) and their compounds can

emerge in noninteger valency.

A necessary condition for nonintegral valence to

occur is that two bounding states of the rare earth,

i.e., 4f

n

(5d6s)

m

and 4f

n1

(5d6s)

m þ1

, are nearly de-

generate. The system may then lower its energy by

adopting a mixture of both EC and an additional

degree of freedom is acquired. On each 4f site charge

fluctuations appear between these configurations on a

typical time scale t

cf

. Experiments probing such sam-

ples on scales much shorter than t

cf

(like XPS) allow

it to observe both configurations, while experiments

with a much longer time scale (like Mo

¨

ssbauer effect)

reveal just the intermediate configuration. In these

systems, the 4f level is pinned to the Fermi energy E

F

,

provoking f electrons to escape into the conduction

band. Hence, the lifetime of the state becomes limited

and the former localized level acquires a narrow

width D with some dispersion and is, therefore, oc-

cupied by a nonintegral number of electrons. The

inverse of D is then given by t

cf

BD/_.

IV is derived from a quantum mechanical hybrid-

ization of two consecutive states a

n

7 f

n

S and a

n1

7

f

n1

S (Lawrence et al. 1981), which can no longer be

considered as a simple superposition. Rather, fluctu-

ations between both states modify physical properties

in a fundamental manner. Features like quenched

magnetic moments, an enhanced Pauli susceptibility,

and a large electronic contribution to the specific heat

may become obvious, which otherwise cannot be

found in both integer valent states involved.

Such homogeneously mixed systems are distin-

guished from the classical ‘‘mixed valence’’ phases like

Fe

3

O

4

or Sm

3

S

4

, where at crystallographic inequiva-

lent lattice sites the cations exhibit different oxidation

states with distinct electronic configurations.

A lattice-related aspect of IV materials is a soft

bulk modulus, indicating the large compressibility of

such systems (Wachter 1994). Since the ionic radius

of IV materials cannot be considered as a ‘‘hard

sphere’’ as for integral valent materials, pressure will

change the degree of IV and thus change the f oc-

cupation, which in turn is related to the ionic radius.

If a pressure induced transition towards an IV state

is of first order, the bulk modulus B

0

becomes infi-

nitely small, and as a consequence, the compressibi-

lity k1/B

0

diverges.

IV systems are also known for a negative elastic

constant c

12

which ensures (in the case of cubic crys-

tals) that even under applied uniaxial pressure the

crystal structure is preserved as it was firstly observed

in TmSe (Batlogg et al. 1979). The negative value of

c

12

also causes a negative Poison ratio c

12

/(c

11

þc

12

).

Measurements of the phonon dispersion relation in

IV materials show a common softening of the acous-

tic and the optical phonon branches when compared

to stable isostructural nonmagnetic systems. More-

over, well-defined crystal field (CF) splitting of the 4f

state has not been found in IV systems yet studied.

1. Some Theoret ical Aspects

The physics of intermediate valent materials is

usually accounted for in terms of the periodic (And-

erson model 1961, see also Electron Systems: Strong

Correlations).

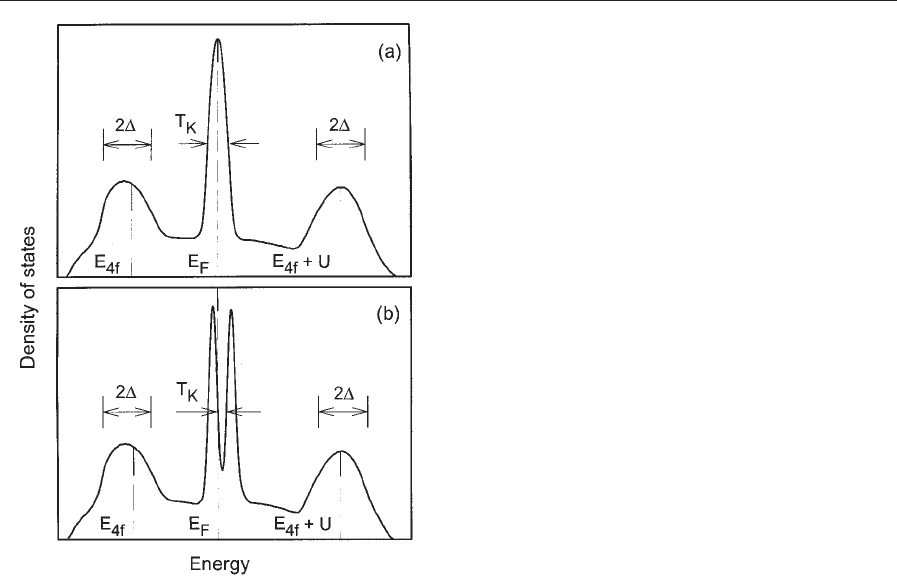

A schematic representation of the DOS for the

impurity version of the Anderson model is drawn in

Fig. 1(a). For large Coulomb repulsion U the f spec-

tral weight is split into two parts located at E

4f

(binding energy of the localized 4f electrons) and

E

4f

þU, having a width DBV

2

/W (V is the hybrid-

ization strength and W is the conduction electron

bandwidth). Due to the removal of spin degrees of

freedom, a narrow many body resonance occurs in

the vicinity of the Fermi energy E

F

as a consequence

of the crossing of the d- and f bands at the Fermi

energy (Martin 1982). IV follows immediately from

the Anderson Hamiltonian for E

4f

- E

F

. The Kondo

effect, on the contrary, is described by this model, if

E

4f

and E

4f

þU are well separated from the Fermi

level (see Kondo Systems and Heavy Fermions: Trans-

port Phenomena).

In the case of a periodic arrangement of the mag-

netic ions, a two peak structure with a gap devel-

ops as a result of the f-d hybridization (Fig. 1(b)).

This hybridization gap is complete if V is

~

k-inde-

pendent. However, if V vanishes at certain points

at the Brillouin zone, the gapping may become in-

complete.

If the f and d electron count is even, and if there

are no other electrons in the conduction band, the

application of Luttinger’s theorem causes E

F

to be

I

317

centered in this gap and the material will be an IV

isolator for T - 0. In fact, many examples of IV

semiconductors are known, possessing an even elec-

tron count such as YbB

12

with 52 valence electrons

per formula unit and an energy gap E

g

B5.2 meV

(Moser et al. 1985). Temperatures of the order of

100 k are then sufficient to smear out the gap and

thermally activate a huge number of carriers. Such

thermal excitations destroy the intersite quantum

coherence, responsible for the hybridization gap.

For an odd electron count, the Fermi energy

should be situated in one of the density peaks above

or below the gap, hence the material will demean as

an IV and heavy fermion metal for T - 0.

2. Experimental Evidence of Intermediate Valence

In general, the lattice parameters of an isotypic series

of rare-earth intermetallics smoothly decrease from

lanthanum to lutetium. This is attributed to the lan-

thanide contraction and ascribed to the fact that

though the electron count of the 4f shell increases, it

cannot completely screen the increase in the nuclear

charge and, therefore, the outer electrons become

constricted. However, compounds with cerium,

samarium, europium, thulium, or ytterbium may

significantly deviate from this simple dependence

since their valency can be larger or smaller than three,

thus cause a decrease or an increase of the unit cell

volume, respectively.

2.1 Samarium and Thulium Monochalcogenides

The monochalcogenides SmS, SmSe, and SmTe crys-

tallize in the f.c.c. structure and are characterized by

a semiconducting behavior owing to an energy gap E

g

between the 4f

6

and the 5d state of about 0.15, 0.45,

and 0.65 eV, respectively (Wachter 1994). CF inter-

action of cubic symmetry splits the 5d orbital into the

lower lying t

2g

band and the e

g

band.

The magnetic susceptibility of this series behaves

like an inhomogeneous mixing of Sm

2 þ

and Sm

3 þ

,

but the finite values for T - 0 imply that the ground

state is homogeneous. The valence fluctuations

render the mixture homogeneous; hence the f

5

spin

memory is lost when the configuration fluctuates

(Lawrence et al. 1981).

Pressure applied to such narrow bandgap systems

can give rise to a semiconductor-metal instability. In

fact, a first order transition was deduced for SmS at

p

c

¼6.5 kbar (Jayaraman et al. 1970), accompanied

by a volume change of about 20%. Slightly above p

c

,

SmS turns golden as the plasma edge moves into vis-

ible and IV occurs. For SmSe and SmTe the pressure-

induced valence transition is continuous and is found

at significant higher values of pressure, i.e., 45 and

60 kbar, respectively (Bucher et al. 1971).

The approach of the ions due to applied pressure

cause the Coulomb potential to increase. Thus CF

splitting of the 5d band grows and eventually leads to

an overlap with the 4f

6

state. Accordingly, the band-

gap closes and 4f electrons empty into the d states.

Upon the enhanced number of conduction electrons,

the lattice starts to shrink, so CF splitting strengthens

further, resulting in some avalanche effect and a first

order phase transition. Since the reduced lattice pa-

rameter stiffens the lattice as a whole, the trivalent

state is not attained. Rather, the process stops at

n ¼2.75 (Kaindl et al. 1984) where the gain in elec-

tronic energy is compensated by the increase of the

lattice energy. In the case of SmSe and SmTe, the gap

in the density of states at E

F

closes before the lattice

softens, and consequently only a second-order phase

transition is observed.

In the case of Tm, both EC, i.e., Tm

2 þ

(J ¼7/2)

and Tm

3 þ

(J ¼6) result in a magnetic ground state.

Such systems can exhibit long-range magnetic order

even in the IV state, which is in contrast to those

based on cerium, samarium, europium, or ytterbium.

The thulium monochalcogenides are of particular

interest. Binary compounds range from metallic

Figure 1

Schematic spectrum of the density of states of (a) the

impurity Kondo case and (b) the Kondo lattice. The

scale T

K

is expanded for clarity.

318

Intermediate Valence Systems

trivalent TmS over IV TmSe to semiconducting

divalent TmTe.

A sketch of the electronic structure and the density

of states of this series is shown in Fig. 2 (Wachter

1994).There is a cross-over from metallic (TmSe) to

isolating behavior (TmTe). The latter exhibits the di-

valent 4f

13

EC, where the localized 4f state is sepa-

rated by an energy gap E

g

B0.3 eV from the bottom

of the 5d-t

2g

band.

When proceeding from TmTe to TmSe or TmS, the

lattice constant shrinks, thus producing chemical

pressure onto the Tm cation. Therefore, crystal field

splitting of the 5d band increases. The bottom of the

conduction band (mostly 5d-t

2g

states) may then

overlap with the 4f

13

level and 4f electrons will spill

into the conduction band.

Stoichiometric TmSe orders antiferromagnetically

below T

N

¼2.9 K (Bjerrum-Moller et al. 1977). The

electrical resistivity in both the paramagnetically and

the magnetically ordered state shows thermally acti-

vated behavior. According to Luttinger’s theorem,

TmSe should be a metal since the compound is

an odd electron system in both EC, 4f

13

and 4f

12

5d.

Antiferromagnetic order below 2.9 k, however, en-

larges the magnetic unit cell which contains an even

number (26) of electrons. The hybridization gap can

then exist with E

F

just in the center, and the system

should behave isolating. However, at m

0

H ¼0.5 T,

TmSe becomes ferromagnetic, thus the folding of the

Brillouin zone vanishes. Consequently, TmSe be-

haves metallic and the system is an IV ferromagnet

(Batlogg et al. 1977).

As for many other IV compounds with the Fermi

level within the hybridization gap, pressure applied to

TmSe (p

c

B30 kbar) will close the bandgap primarily

due to the growing overlap of the crystal field split

5d band with the 4f

13

state (Wachter 1994).

Besides, the pseudobinary TmSe

1x

Te

x

allows to

realize a novel feature in condensed matter physics,

the excitonic insulator, which is characterized by a

Bose-Einstein condensation of quasi-particles into a

coherent exciton phase (Neuenschwander and Wach-

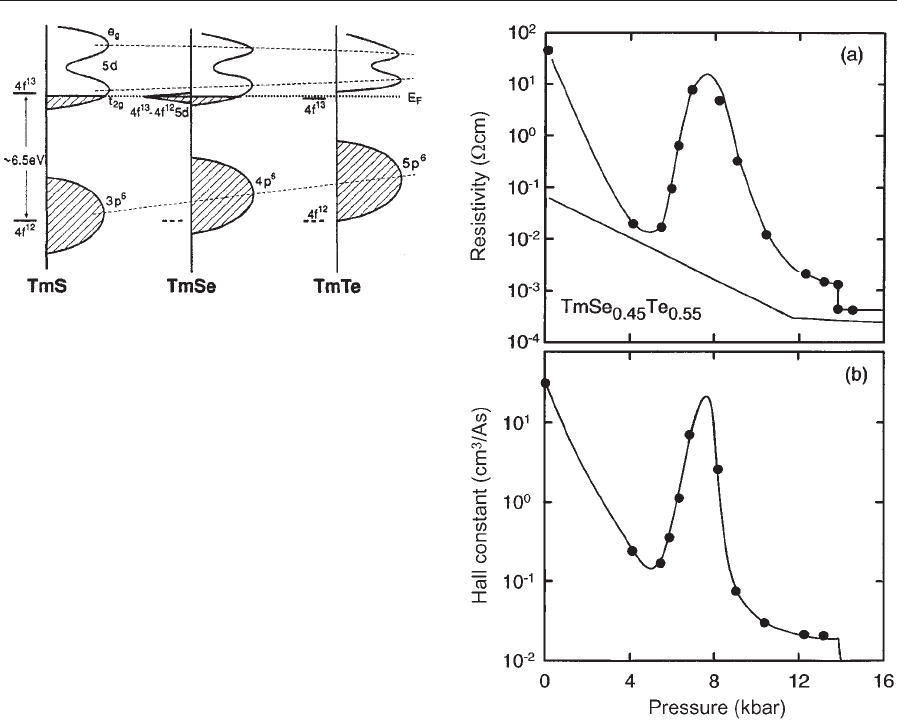

ter 1990). Figure 3 shows the pressure dependence of

the electrical resistivity of TmSe

0.45

Te

0.55

at high and

low temperatures and the Hall constant. The most

striking feature with respect to the resistivity at

T ¼4 K is that after the expected initial decrease of

r(p), a rapid rise in a narrow pressure range from

about 5 kbar to 8 kbar occurs. Beyond this pressure,

the resistivity decreases again and furthermore ex-

hibits a first order phase transition near p ¼14 kbar.

Figure 2

Electronic structure and density of states of the Tm

monochalcogenides normalized to the Fermi energy E

F

(dotted line). The dashed lines through the density of

state peaks serve as a guide to the eyes.

Figure 3

(a) Pressure dependence of the resistivity of

TmSe

0.45

Te

0.55

at 300 K (lower curve) and at 4.2 K

(upper curve). At 300 K the semiconducting to metal

transition is at p

c

¼11.5 kbar and for T ¼4.2 K at

p

c

B14 kbar. (b) Pressure-dependent Hall constant R

H

at 4.2 K.

319

Intermediate Valence Systems