Bradley D., Russell D.W. (eds.) Mechatronics in Action: Case Studies in Mechatronics - Applications and Education

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

86 D. Seward

Drive-by-wire

Many modern aircraft have now made the transition to “fly-by-wire” which

involves the replacement of mechanical linkages to the control flaps by electronic

signals generated by multiple computers. Cars have already started to move in this

direction with electrical power steering, parking brakes, communications buses

and wire-controlled throttles. The trend is expected to continue, however, there are

clear safety concerns over removing the physical links to such items as the main

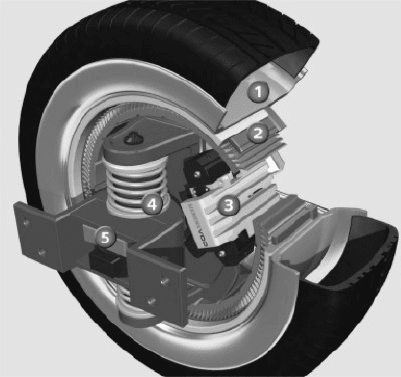

brakes. An extension of this concept, the ‘smart wheel’ as developed by Siemens,

is shown in Figure 6.2. [4].

Fig. 6.2 Siemens eCorner ‘smart wheels’ future concept. The hub motor (2) is located inside the

wheel rim (1) and the electronic wedge brake (3) uses pads driven by electric motors. An active

suspension (4) and electronic steering (5) replace conventional hydraulic systems

6.1.2 Drivers for Change

It is interesting to consider why, after a hundred years of car production, the

mechatronic revolution took hold in the way that it did. It is possible to identify a

series of powerful drivers that coincided at that time:

Reliability

It is generally accepted that the modern motor car is now more reliable than ever

before. This is partly due to pressure from the car-buying public and competition

between manufacturers. However, a key enabling technology is the widespread

adoption of electronic ignition and fuel injection. By far, the majority of problems

associated with poor starting or bad running were related to the mechanical wear

Mechatronics and the Motor Car 87

of components in the ignition and fuel delivery systems. Modern electronic engine

management systems largely cured these problems.

Economy and Performance

It was traditionally recognised that a car’s engine can be optimised for either

economy in terms of fuel consumption or performance in terms of power output.

The standard approach for increasing performance was to increase the flow of

air/fuel mixture through the engine by means of larger and multiple carburettors

which invariably had a deleterious effect on fuel consumption.

Paradoxically, the first commercial adoption of electronic fuel injection was on

high performance ‘GTI’ models where the main emphasis was on further increases

in power. However, it was quickly realised that the much enhanced control over

the fuel/air mixture that electronic fuel injection afforded could also be exploited

for significant benefits in economy. More recently, this technology has enabled a

major transformation in both the economy and performance of diesel engines.

Security

Pressure from insurance companies and the police led to a demand for significant

improvements in vehicle alarm and immobilisation systems.

Environmental Protection

Once it became clear that there was a valid technical solution, legislation was

introduced by governments to reduce harmful emissions from vehicles. Apart

from the complete abolition of lead additives in petrol, the main emphasis was on

the reduction of carbon monoxide from exhaust gases.

Exemptions were introduced for older vehicles because traditional mechanical

carburettor systems are not capable of delivering the low levels demanded by the

legislation. Thus, manufacturers were forced to move to mechatronic engine

management.

Safety

Customer demand for increased passenger safety led to the widespread adoption

of stability enhancing technologies such as ABS brakes and traction control as

well as measures to mitigate the effects of a collision such as air bags and seat belt

tensioners.

Enhanced Functionality

Mechatronics has provided manufacturers with the ability to offer enhanced

functionality across many aspects of the motor car. Manufacturers have used this

opportunity to distinguish basic models from top-of-the-range models and to

88 D. Seward

generate additional income from the provision of factory-fitted extras. As specific

systems have become more cost effective, competition between manufacturers has

been an important driver in moving enhanced features down the model range.

6.2 Engine Basics

Before considering three automotive mechatronic systems in detail, it is necessary

to understand the basic operation of the internal combustion engine. The rotating

crankshaft at the bottom of the engine is connected to the piston and causes it to

rise and fall in the cylinder. The valves at the top of the engine open and close at

appropriate times in order to admit fuel to the cylinder and to allow burnt exhaust

gasses to be expelled. The most common car engine uses the four-stroke Otto

cycle [5].

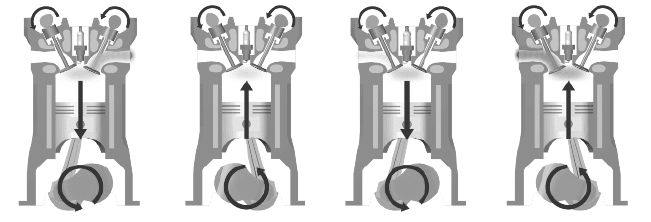

(a) (b) (c) (d)

Fig. 6.3 The four-stroke Otto cycle, (a) induction stroke, (b) compression stroke, (c) power

stroke, and (d) exhaust stroke

The cycle starts with the induction stroke of Figure 6.3 (a). With the piston

moving downwards in the cylinder, the inlet valve opens and the air/petrol mixture

is sucked into the cylinder. When the piston is at the bottom, the inlet valve closes.

The piston then starts to move upwards, compressing the fuel mixture to about

a tenth of its original volume. This is the compression stroke of Figure 6.3 (b).

When the piston is close to the top, the spark plug ignites the fuel, causing

combustion and the expanding gasses to drive the piston downwards in the power

stroke as shown in Figure 6.3 (c). The final stage is the exhaust cycle of Figure 6.3

(d). The piston rises again and the exhaust valve opens to allow the burnt gases to

escape. The cycle then repeats. Thus, the crankshaft makes two revolutions in

each cycle.

The four-stroke engine can have from one to twelve cylinders, though the

commonest number for passenger cars is four.

Mechatronics and the Motor Car 89

It can be concluded from the above that three key system requirements are:

1. The spark plug ignition must be precisely timed in relation to the movement of

the piston. Sparking normally occurs just before the piston reaches the top (said

to be advanced), though the precise position varies with fuel type.

2. The ratio of air/petrol fuel mixture must be carefully controlled. The ‘ideal’

mixture is known as the stochiometric ratio and is 14.68 parts of air to one part

of fuel by weight. A slightly lower ratio (12.6:1) is known to give maximum

power and a higher ratio (15.4:1) is best for economy [6].

3. The valves must open and close at exactly the right stage of the cycle. This is

one element of the system that is still under purely mechanical actuation (a

camshaft driven by a belt or chain from the crankshaft). However, electronic

valve control is an active research area and promises even more benefits in

terms of economy and performance in future vehicles.

6.3 The Mechanical Solution for Ignition Timing

and Fuel Delivery

6.3.1 Traditional Mechanical Ignition Timing

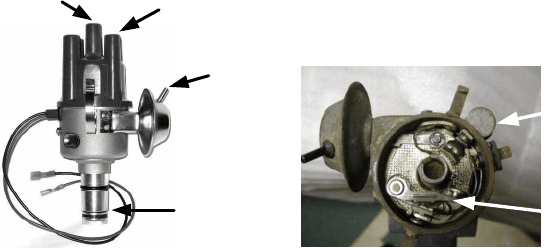

The main component in traditional mechanical ignition timing is the distributor of

Figure 6.4 (a) [7]. The purpose of the distributor is to trigger a release of high

voltage electricity from the coil and distribute it to the appropriate spark plug. The

triggering is performed by the contact breaker or points shown in Figure 6.4 (b).

An upper central shaft in the distributor is turned by a lower shaft connected to the

engine which causes a multi-sided cam to revolve inside the body of the

distributor. The cam separates the circuit breaker each time a spark is required.

The rotor-arm on top of the rotating shaft then makes contact with the appropriate

plug lead terminal to send the high voltage to the appropriate spark plug. The

condenser (or capacitor) is present to prevent the initial spark jumping across the

contact breaker gap and eroding the contact breaker surfaces.

90 D. Seward

Vacuum

advance

High voltage

input from coil

High voltage output

to spark plug

Drive shaft

from engine

Contact

breaker

points

Condenser

(a) (b)

Fig. 6.4 A 4-cylinder distributor, (a) external view, and (b) internal view

The initial ignition timing is set by rotating the body of the distributor around

the central shaft so that the cams break the points at the correct time. However, for

maximum efficiency and performance, the spark plug needs to fire increasingly in

advance of the piston reaching the top of the cylinder (Top Dead Centre or TDC)

as the engine speeds up. This is achieved by the incorporation of centrifugal

weights that vary the angular relationship between the upper and lower shafts. The

aim is for the spark plug to fire so as to give the relatively slow combustion

process enough time to develop maximum pressure just as the piston is starting to

descend. If the spark timing is too early, there is the danger that the maximum

cylinder pressure is developed whilst the piston is still rising. This produces huge

stresses in the engine and is known as knocking. Paradoxically higher octane fuels

burn slower and so the ignition timing needs to be more advanced to allow more

time for combustion. The danger however is that if the owner fills-up with lower

octane fuel, there is the likelihood of knocking.

Yet another refinement is the vacuum advance. At idle, when little air/fuel

mixture is available to the engine, the inlet manifold will be at negative pressure.

This is used via a diaphragm to slightly rotate the plate that supports the contact

breaker points to again advance the spark.

As previously stated, many reliability problems with cars originated with the

ignition system. The contact breaker points in particular are subject to both wear

and the accumulation of dirt. They require routine replacement and adjustment to

keep the engine running smoothly and efficiently.

6.3.2 Fuel Delivery – the Carburettor

The carburettor was invented in 1895 by Karl Benz and was still in use a hundred

years later. Its basic function is to deliver the optimum mix of air and petrol to the

Mechatronics and the Motor Car 91

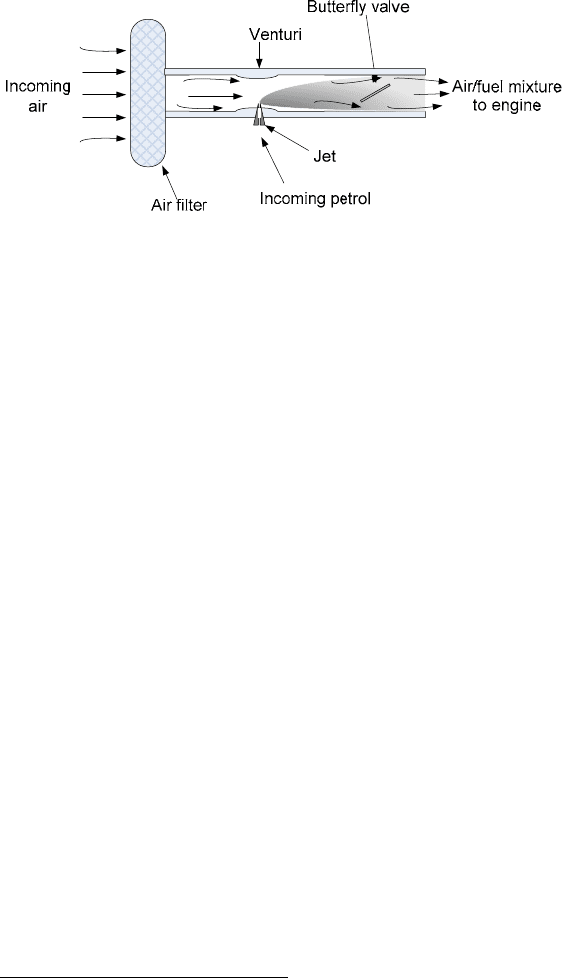

cylinder prior to combustion. Referring to Figure 6.5, the basic operating principle

is as follows [8]:

Fig. 6.5 The basic carburettor

1. When a piston descends in the cylinder of an engine in the induction cycle, the

inlet valve is open. This sucks in a volume of air/fuel mixture roughly equal to

the displaced volume of the cylinder.

2. This action pulls in air through a filter and into the body of the carburettor. This

is in the form of a Venturi tube in order to accelerate (and hence reduce the

pressure) of the incoming air. The tube also contains a butterfly valve and a

fuel jet. The butterfly valve, which determines the volume of the air flow, is

connected to the accelerator pedal and is the means by which the driver

controls the output of the engine and hence the speed of the car.

3. As the air flows past the jet at reduced pressure, it draws in fuel which divides

into a spray of small droplets and mixes with the air (an aerosol)

2

. The fuel is

supplied from a reservoir built into the body of the carburettor, the level of

which is controlled by a float.

In the simplest form of carburettor, the proportions of the air/fuel mixture are

determined by the jet diameter and its position in the air flow. This works

reasonably well for steady power output at high engine speeds, though there are

problems at other times:

• When the engine is cold the mixture needs to be much richer in order to get the

engine to start.

• When the engine is ticking over at low speed, the air flow through the venture

is not sufficient to produce adequate fuel flow.

• During sudden acceleration of the car, the air can gain speed quicker than the

heavier fuel producing a lean mix when a rich one is required.

Over time, the mechanical complexity of carburettors was increased in order to

address these problems and to attempt to produce an optimum mix for all

conditions. One such refinement is the variable choke carburettor where a damped

2

The same principle as is used in a scent spray

92 D. Seward

piston rises and falls in the Venturi tube in an attempt to keep the speed of air flow

across the jet constant [9]. At the same time, a tapered needle connected to the

piston moves in and out of the jet, altering its effective diameter. In addition, some

carburettors use a pump to boost fuel flow during rapid acceleration.

The problem of cold starting was resolved by means of a choke which

simultaneously reduces air flow and increases fuel flow. For many years, these

were hand operated, but eventually became automatic based on some kind of

temperature sensor.

It is clear that the carburettor evolved to become a relatively complex and

expensive piece of precision mechanical engineering. However, even in its most

advanced form, it could not deliver the precision of fuel metering required to meet

the demands of the modern car engine. This is also the case for a new carburettor.

Older carburettors, where the needles and jets have been subjected to wear or poor

adjustment, present even greater problems. Only an electronic fuel injection

system can consistently deliver adequate fuel control in terms of performance,

economy and environmental emissions.

6.4 The Mechatronic Solution to Engine Management

The first component to be replaced by mechatronics was the troublesome contact

breaker points. From the 1970s onwards, these were replaced by a non-contact

sensor inside the distributor that consisted of a rotating toothed armature (one

tooth for each cylinder) that induces a signal from an electromagnetic transponder

each time a tooth passes in front of it [7]. This signal was then sent to an electronic

ignition control unit that triggered the firing of the coil and hence the spark. This

simple innovation produced a stronger and more reliable spark and removed the

need for the replacement and maintenance of points. At this stage, the mechanical

centrifugal and vacuum advance systems remained.

The real revolution came in the mid-1980s when advances in electronic fuel

injection and microprocessor technology enabled complete control over both

ignition and fuel delivery to be contained within a single Engine Control Unit

(ECU). This allows for a much clearer separation between sensing, processing and

actuation in accordance with mechatronic principles. Both the distributor and the

carburettor have now become redundant [6, 10].

6.4.1 Sensors

Crankshaft and camshaft sensors generally consist of toothed wheel armatures

passing an electromagnetic Hall Effect sensor. By counting the pulses, the ECU

can evaluate firstly engine speed in rpm, and secondly, the actual current position

of the pistons and the stage in the four-stroke cycle. The armatures generally

Mechatronics and the Motor Car 93

contain a missing tooth so that the ECU can identify this and synchronise with a

specific piston position. Because the crankshaft rotates twice within each four-

stroke cycle and it is important for the ECU to know the current stage of the cycle,

some indication is also required from the camshaft as to which spark plug is about

to fire.

A knock sensor is essentially a microphone fitted to part of the engine block to

listen for the distinctive sound of engine knocking, indicating that the spark is too

far advanced. The microphone is associated with a bandpass filter to identify the

relevant knocking frequencies and inform the ECU.

A Lamda or oxygen sensor is placed in the exhaust system to measure any un-

burnt oxygen in the waste gasses. They are primarily used to control the air/fuel

mix ratio as richer fuel mixes tend to burn quicker, requiring less ignition advance.

A lambda sensor contains a ceramic layer which produces a current in the

presence of excess oxygen. This current can then be detected by the ECU. They

only work effectively when hot, and hence the ECU may be told to ignore the

output when the exhaust system is cold. In order to reduce the waiting time, some

sensors are fitted with heaters and are known as Heated Exhaust Gas Oxygen

sensors or HEGOs.

A throttle position sensor is a simple rotary potentiometer usually connected to

the end of the butterfly valve in the air induction system. Knowing the degree to

which the valve is open gives the ECU a good indication of the driver’s

intensions. By looking at direction of movement and rates of change of the valve,

the ECU can determine if the vehicle is accelerating, decelerating or cruising; all

of which influence ignition timing and fuel ratio.

The mass air flow sensor (MAF) is contained in the air induction system and

provides information on the mass of air entering the engine which is obviously

key to determining the appropriate amount of fuel to inject. The sensor consists of

a heated wire element that is maintained at constant temperature in the varying air

flow. The current required to maintain this temperature is directly proportional to

the mass of air flowing.

Earlier sensors measured volume of flow, but as the density of air reduces with

temperature, additional temperature information was required to calculate the

mass of air with sufficient accuracy.

A water temperature sensor allows the ECU to detect a cold start and hence

enrich the fuel. The normal fuel mixture is then adopted when the temperature

reaches a pre-set value.

6.4.2 Actuators

Ignition coils still provide the high voltage for the spark plugs, but in the absence

of a distributor, modern systems often use individual coils for each plug or pair of

plugs. The triggering signal comes directly from the ECU.

94 D. Seward

Fuel Injectors add a spray of fuel through a nozzle to the incoming air flow in

order to achieve the appropriate air/fuel mix ratio. Current practice is to use one

injector per cylinder, all of which are fed by a constant-pressure fuel line.

Variation in the amount of fuel added is determined by very precise control over

the time that the injector valve is opened on each induction cycle. The opening of

the valve is affected by a signal from the ECU that powers a solenoid within the

injector. Closure is by means of a return spring and the fuel line pressure.

6.4.3 Processing

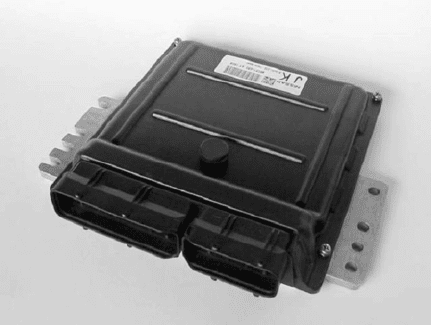

The ECU generally takes the form of a module such as that of Figure 6.6 within

the engine compartment. The module contains:

• all the electronics for receiving and conditioning the signals from the sensors;

• a powerful processor for interpreting the signals and determining the outputs;

• output circuits and amplifiers for driving the ignition coils and fuel injectors.

In addition, the ECU will contain a fault memory that can be read when the

vehicle is serviced. The essence of determining the most appropriate system

outputs is the reading of values from look-up tables or maps such as that of Table

6.1.

Fig. 6.6 A typical ‘black box’ Engine Control Unit (ECU) module

Mechatronics and the Motor Car 95

Table 6.1 A portion of the fuel map for a high-revving motorcycle engine

Fuel Map

Throttle Position

RPM 0.00 4.00 7.00 11.00 16.00 22.00 29.00

500 3.06 3.65 3.65 4.64 4.80 5.00 5.14

1000 2.08 2.78 3.34 3.34 4.45 4.85 5.12

2000 2.07 2.78 3.34 3.34 4.45 4.85 5.12

3000 1.85 2.78 3.34 3.34 4.45 4.85 5.12

4000 1.75 2.62 3.15 3.15 4.20 4.58 4.83

4500 1.75 2.62 3.15 3.20 4.25 4.71 5.05

5000 1.75 2.62 2.60 2.97 4.04 4.43 4.73

6000 1.72 2.57 2.11 2.64 3.33 3.77 4.14

6500 1.63 2.44 2.31 2.64 3.41 3.80 4.11

7000 1.61 2.42 2.59 2.76 3.62 4.00 4.27

7500 1.60 2.40 2.72 2.43 3.37 3.80 4.15

8000 1.58 1.90 1.90 2.09 3.13 3.61 4.03

9500 4.67 5.08 5.21 5.26 5.10 5.32 5.19

10000 4.67 5.08 5.27 5.33 5.29 5.45 5.19

Injector opening time (µs)

Aftermarket ECUs that are reprogrammable are available for car developers

and in this case, the engine maps will be stored on a separate EPROM chip within

the ECU. Such ECUs are provided with software that can be used in conjunction

with a laptop to tune the engine while running. The basic tables are the ignition

map and the fuel map. In both cases, one axis of the map represents the speed of

the engine (rpm) and the other some indication of engine load. Table 6.1 shows an

example of the fuel map for a motorcycle engine. In this case, the vertical axis is

rpm and the horizontal axis represents the percentage of throttle opening. The

figures in the cells indicate the time in microseconds that the injector should

remain open for.

The data in the above table is often represented as a 3D surface, as shown in

Figure 6.7, which is clearly the origin of the term engine ‘map’. Figure 6.8 then

shows a typical architecture for an engine management system. At the heart is a

powerful processor such as the Motorola MPC 500 32-bit chip [11].