Boyer George R. An Economic History of the English Poor Law, 1750-1850

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The Old Poor Law in Historical Perspective 57

evident that the labour of those who are not supported by parish assistance, will

purchase a smaller quantity of provisions than before, and consequently, more

of them must be driven to ask for support. (1798: 83-4)

Thus,

in the long run, "the poor-laws tend in the most marked manner

to make the supply of labour exceed the demand for it ... and thus

constantly to increase the poverty and distress of the labouring classes of

society" (1817: II, 371).

7

Malthus's adherence to the wages-fund doctrine led him to criticize

parish make-work projects. He argued that it was a "gross error" to

suppose "that the funds for the maintenance of labour . . . may be

increased at will, and without limit, by a fiat of government, or an

assessment of the overseers" (1807a: II, 102). Like Eden, he felt that

attempts by parishes to employ the poor in the production of manufac-

tured goods would "throw out of employment many independent work-

men, who were before engaged in fabrications of a similar nature"

(1807a: II, 108).

Malthus concluded that the distress of the laboring poor was caused

by the "absurd" and "arrogant" administration of poor

relief,

rather

than by changes in the economic environment. He attempted to refute

the hypothesis that the high levels of relief expenditures during the

Napoleonic Wars had been attributable to the high price of food by

pointing out in 1817 that "we have seen these necessaries of life experi-

ence a great and sudden fall [in price], and yet at the same time a still

larger proportion of the population requiring public assistance" (1817:

II,

360). Given the cause of distress, the solution was obvious: The

granting of relief to able-bodied laborers had to be abolished. Malthus

argued that the abolition of poor relief would benefit the poor in the

long run. He proposed a plan of gradual abolition in which no child born

after a certain date would ever be able to obtain parish relief (1807a: II,

320-4).

Moreover, he argued against replacing poor relief with either a

guaranteed minimum wage, as proposed by Davies, or an allotment

scheme, as proposed by both Eden and Davies. A guaranteed minimum

wage would not work because it would not allow the wage rate "to find

its natural level," determined by "the relations between the supply of

provisions, and the demand for them." It was important for the wage

7

In a rare agreement with Malthus, David Ricardo

(1821:

105-6) wrote that "the clear and

direct tendency of the poor laws ... is not, as the legislature benevolently intended, to

amend the condition of the poor, but to deteriorate the condition of both poor and rich;

instead of making the poor rich, they are calculated to make the rich poor."

58 An Economic History of

the

English Poor Law

rate to reach its natural level because this "expresses clearly the wants of

the society respecting population" (1807a: II, 89-90). With respect to

allotment schemes, Malthus devoted several pages to criticizing Arthur

Young's plan to grant each rural laborer with three or more children

"half an acre of land for potatoes; and grass enough to feed one or two

cows."

According to Malthus, "Young's plan would be incomparably

more powerful in encouraging a population beyond the demand for

labour than our present poor laws" (1807a: II, 376). Malthus blamed the

poverty in Ireland on the ready availability of small allotments of land.

He argued that because of "the facility of obtaining a cabin and pota-

toes . . . , a population is brought into existence, which is not demanded

by the quantity of capital and employment in the country; and the conse-

quence of which must therefore necessarily be ... to lower in general

the price of labour" (1807a: II, 374-5). Malthus concluded that it was

best to leave the poor to their own devices, since that would encourage

them to depend on themselves and to practice moral restraint.

The indictment of the Poor Law contained in Malthus's Essay on

Population received considerable attention in Parliament during the

post-Napoleonic War period. Between 1817 and 1831, several parlia-

mentary committees were appointed to study the economic effects of the

system of outdoor relief and to consider possible methods for Poor Law

reform. The most important document to come out of these committees

was the 1817 report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons

(Pad. Papers 1817: VI).

K

The report contained little that was new in its

analysis of the Poor Law. Rather, it relied heavily on the arguments of

previous reformers, Malthus in particular.

The report began, in typical fashion, by maintaining that the granting

of outdoor relief to able-bodied laborers instilled bad habits in the work-

ing class.

9

It presented evidence that relief expenditures had been con-

tinually increasing since 1776, and argued that this increase was for the

most part "independent of the pressure of any temporary or accidental

circumstances, . . . the rise in the price of provisions and other neces-

8

Poynter (1969:

245)

called

the

1817 report

"the

baldest

and

most dogmatic summary

of

the abolitionist case published"

in the

post-Napoleonic

War

period.

9

The report claimed that outdoor relief produced

"the

unfortunate effect

of

abating those

exertions

on the

part

of

the labouring classes,

on

which, according

to

the nature

of

things,

the happiness

and

welfare

of

mankind

has

been made

to

rest. By diminishing this natural

impulse

by

which

men are

instigated

to

industry

and

good conduct,

by

superseding

the

necessity

of

providing

in the

season

of

health

and

vigour

for

the wants

of

sickness

and old

age,

. . .

this system

is

perpetually encouraging

and

increasing

the

amount

of

misery

it

was designed

to

alleviate"

(Pad.

Papers 1817:

VI, 4).

The Old Poor Law in

Historical Perspective

59

saries of life," and the increase in population (Pad. Papers 1817: VI, 5).

Rather, it was the result of "evils which are inherent in the system." The

report predicted that "the amount of the assessment will continue as it

has done, to increase till ... it shall have absorbed the profits of the

property on which the rate may have been assessed, producing thereby

the neglect and ruin of the land" (Pad. Papers 1817: VI, 8).

Like Eden and Malthus, the report rigidly adhered to the wages-fund

doctrine. It maintained that:

what number of persons can be employed in labour, must depend absolutely

upon the amount of the [wages] funds, which alone are applicable to the

maintenance of labour. In whatever way these funds may be applied or ex-

pended, the quantity of labour maintained by them . . . would be very nearly

the same. . . . [W]hoever therefore is maintained by the law as a labouring

pauper, is maintained only instead of some other individual, who would other-

wise have earned by his own industry, the money bestowed on the pauper.

(Pad. Papers 1817: VI, 17)

In other words, there existed a one-to-one trade-off between poor relief

and wage income, so that governmental make-work projects were al-

ways counterproductive. The objective of finding employment for all

who required it was "not in the power of any law to fulfill" (Pad. Papers

1817:

VI, 17).

Ironically, the 1817 report did not urge that the provision of outdoor

relief to able-bodied laborers be immediately abolished, believing this to

be impractical at the time. It did suggest, however, that at some time in

the future, "under favourable circumstances of the country," the system

of outdoor relief should be ended. Abolition would result in an increase

in "the natural demand for labour" and would also "have the effect of

gradually raising the wages of labour" because it was "the obvious inter-

est of the farmer" to provide each of his workers with "such necessaries

of life as may keep his body in full vigour, and his mind gay and cheer-

ful"

(Pad. Papers 1817: VI, 18-19).

The major arguments for abolishing the Poor Law, therefore, were

laid out 17 years before the appearance of the 1834 Poor Law Report

and the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act. The intellectual roots

of the abolitionists' arguments were Townsend's

Dissertation

on the

Poor

Laws, which argued that relief was unnecessary; the wages-fund doc-

trine,

which was used by Eden and Malthus to argue that relief lowered

wage rates; and Malthus's theory of population, which showed that

outdoor relief increased the number of paupers in the long run.

60 An Economic History of

the

English Poor Law

2.

The

Poor

Law

Report

of 1834

The postwar parliamentary committees that were set up to consider

various aspects of poor relief made no attempt to abolish or reform the

Poor Law. The "impotence" of Parliament was finally ended when the

Royal Commission to Investigate the Poor Laws was created by the new

Whig government in February 1832. Nine persons were chosen to serve

on the commission; by far the two most important members were Nassau

Senior, a lawyer and political economist, and Edwin Chadwick, a lawyer

and journalist as well as a disciple of Jeremy Bentham.

10

The first task of the commission was the collection of data on the

economic effects of outdoor

relief.

The commissioners relied on two

types of evidence. First, they drew up and distributed two sets of ques-

tionnaires, known as the Rural and Town Queries, which were mailed to

parishes during the spring of 1832. The commissioners then appointed

26 assistant commissioners to visit parishes throughout England and

Wales. The assistant commissioners were directed to ascertain the ef-

fects of outdoor relief "on the industry, habits, and character of the

labourer, the increase of population, the rate of wages, the profits of

farming, the increase or diminution of farming capital, and the rent and

improvement of land" (Royal Commission 1833: 417). Those who came

upon parishes with a seeming redundancy of population were to deter-

mine whether the redundancy was "occasioned either by the want of

capital among the farmers, or by the indolence or unskillful habits of the

labourers." If the unemployment appeared to be caused by the existence

of "more labourers than could be profitably employed at the existing

prices of produce, although the labourers were intelligent and industri-

ous,

and the farmers wealthy," the assistant commissioners were to ascer-

tain to what extent the redundancy

has been occasioned by the stimulus applied to population by the relief of the

able-bodied; and for that purpose inquire into the frequency of marriages where

the husband at the time, or shortly before or after the time of the marriage, was

in receipt of parish

relief,

and into the proportion of the number of such mar-

riages to those of independent labourers. (Royal Commission 1833: 418)

In other words, the commissioners assumed that unemployment was

caused either by the indolence of labor, as argued by Townsend and

10

Detailed analyses

of the 1834

Poor

Law

Report

can be

found

in

Cowherd

(1977:

204-

82),

Webb

and

Webb

(1929:

1-103), and

Poynter

(1969:

316-29).

See

also Williams

(1981:

52-8).

The Old Poor Law in Historical Perspective 61

Malthus, or by an increase in population caused by the system of out-

door

relief,

as argued by Malthus.

The assistant commissioners' reports were completed by January 1833.

The information from these reports, along with information from the

Rural and Town Queries, was selectively used in the general report of the

Royal Commission (Royal Commission 1834), written almost entirely by

Senior and Chadwick, and published in March 1834. Publication of the

assistant commissioners' reports and the answers to the Rural and Town

Queries followed later in 1834. In all, the report filled 12 volumes of

Parliamentary Papers containing thousands of pages. Unfortunately, a

large amount of the material contained in the assistant commissioners'

reports and the Queries was ignored by Senior and Chadwick, so that the

general report's analysis of the use of outdoor relief was little more than a

greatly expanded version of the 1817 House of Commons Report on the

Poor Law, full of detailed examples of the bad effects of the system of

outdoor relief on laborers, landlords, large farmers, small farmers, and

tradesmen.

The major conclusion reached by the report was that all forms of

outdoor relief produced bad effects and should therefore be abolished.

It contended that

out-door relief . . . appears to contain in itself the elements of an almost indefi-

nite extension; of an extension, in short, which may ultimately absorb the whole

fund out of which it arises. Among the elements of extension are the constantly

diminishing reluctance to claim an apparent benefit, the receipt of which im-

poses no sacrifice, except a sensation of shame quickly obliterated by habit, even

if not prevented by example. (Royal Commission 1834: 44)

The effect of the allowance system, which granted "relief in aid of

wages" to privately employed laborers, was to

diminish, we might almost say to destroy, all ... qualities in the labourer. What

motives has the man who . . . knows that his income will be increased by noth-

ing but by an increase of his family, and diminished by nothing but by a diminu-

tion of his family, that it has no reference to his skill, his honesty, or his

diligence - what motive has he to acquire or to preserve any of these merits?

Unhappily, the evidence shows, not only that these virtues are rapidly wearing

out, but that their place is assumed by the opposite vices. (1834: 68)

These same criticisms were applied to the policy of granting outdoor

relief to unemployed laborers, which also was criticized for granting

benefits that were as large as the wage rates paid by farmers while

62 An Economic History of

the

English Poor Law

requiring only a small amount of work from the recipients (1834: 39).

The labor rate and the roundsman system also made laborers indolent.

Under

the

labour-rate system

[and the

roundsman system] relief

and

wages

are

confounded.

The

wages partake

of relief, and the

relief partakes

of

wages.

The

labourer

is

employed,

not

because

he is a

good workman,

but

because

he is a

parishioner.

He

receives

a

certain

sum, not

because

it is the

fair value

of his

labour,

but

because

it is

what

the

vestry

has

ordered

to be

paid. Good conduct,

diligence, skill,

all

become valueless.

Can it be

supposed that they will

be pre-

served? (1834: 219-20)

The labor rate and the roundsman system were further criticized for

allowing labor-hiring farmers to pass some of their labor costs to small

occupiers, tradespeople, and householders (1834: 197, 210-11). Since

Parliament had given sanction to the use of labor rates only two years

before 1834, it is surprising that they were criticized so severely in the

report.

11

Unlike earlier critiques of the Poor Laws, the 1834 report gave an

explanation for the widespread adoption and persistence of policies

granting outdoor relief to able-bodied laborers. Employers supported

the use of outdoor relief because it

enables them

to

dismiss

and

resume their labourers according

to

their daily

or

even hourly want

of

them,

and to

reduce wages

to the

minimum,

or

even below

the minimum

of

what will support

an

unmarried

man, and to

throw upon others

the payment

of a

part

... of the

wages actually received

by

their labourers.

(1834:

59)

Of course, the granting of outdoor relief made laborers indolent and

thereby reduced their productivity, so that ultimately "the farmer finds

that pauper labour is dear, whatever be its price." However, the decline

in labor productivity evolved slowly over time, so the farmer benefited

from the use of outdoor relief in the short run (1834: 71). In the long

run, "when the apparently cheap labour has become really dear," the

farmer "can either quit at the expiration of his lease, or demand on its

renewal a diminution of rent" (1834: 73).

12

Whereas leaseholders were

thus encouraged to support the allowance system, farmers who owned

11

An

entire chapter

of the 1834

report

was

devoted

to

criticism

of the

labor rate. Appar-

ently Senior

and

Chadwick believed that

the

recent popularity

of

labor rates made

it

important

to

present

an

especially detailed critique

of

that method

of

outdoor

relief.

12

The

report concluded that farmers' ability

to

profit from

the use of

outdoor relief

by

reducing their wage bill "accounts

for the

many instances

in our

evidence

... of the

indifference

of the

farmers

in

some places

to

poor-law expenditure,

and in

other places

to their positive wish

to

increase

it"

(1834:

72).

The Old Poor Law in

Historical Perspective

63

their land were not. A landowner

u

may be expected to oppose the

introduction of allowance, knowing that for giving up an immediate

accession to his income he will be repaid, by preserving the industry and

morality of his fellow-parishioners, and by saving his estate from being

gradually absorbed by pauperism" (1834: 73). The seeming popularity of

the allowance system, therefore, could only be explained by the political

dominance of leaseholders in most rural parishes in the south and east.

13

The report rejected the proposal that outdoor relief be replaced by a

policy of supplying laborers with allotments, although the renting of

land to laborers by individual farmers was supported. There was no need

for parliamentary intervention, since the renting of allotments could be

made "beneficial to the lessor as well as to the occupier," and "a practice

which is beneficial to both parties, and is known to be so, may be left to

the care of their own self-interest" (1834: 193-4). However, although

allotments reduced relief expenditures in the short run, the report ar-

gued that they would not reduce expenditures in the long run. The

amount of land available for allotments "is limited, and the number of

applicants is rapidly augmenting, [so that] every year would increase the

difficulty of supplying fresh allotments, and diminish their efficiency in

reducing the increasing mass of pauperism" (1834: 194).

The most striking feature of the report is that it made no attempt to

study the causes of the unemployment that was very much in evidence in

the rural south and east. None of the questions in the Rural Queries dealt

with the causes of unemployment, and the instructions to the assistant

commissioners requested them merely to ascertain whether unemploy-

ment was caused by the indolence of laborers or by increases in popula-

tion brought about by the allowance system. Despite the indifference of

the commissioners, many parishes responding to the Rural Queries dis-

cussed the causes of their unemployment problems, and several of the

assistant commissioners wrote of the economic causes of unemployment,

and especially seasonal unemployment, in their

reports.

This information

was ignored by Senior and Chadwick, however, so that the commission's

report made no mention of the economic causes of unemployment.

Rather, the report maintained that existing unemployment was an artifi-

cial creation of the system of outdoor

relief.

To support this contention,

evidence was presented of a decline in unemployment rates in parishes

13

The report does not explain why landowners would allow leaseholders to adopt a system

that would cause the parish to be "gradually absorbed by pauperism."

64 An Economic History of

the English

Poor Law

where the use of outdoor relief had been discontinued

(1834:

233-7). The

report concluded that the unemployment problem "would be rapidly

reduced and ultimately disappear" upon the abolition of policies granting

outdoor relief to able-bodied laborers (1834: 354).

The report recommended that outdoor relief be replaced by a policy

of "less-eligibility," the purpose of which was to lower the utility level of

laborers supported by the parish below that of the lowest-paid indepen-

dent laborers. The report contended that the "most essential of

all

condi-

tions"

imposed on the recipient of relief should be that

his situation on the whole shall not be made really or apparently so eligible as the

situation of the independent labourer of the lowest class. . . . [I]n proportion as

the condition of any pauper class is elevated above the condition of independent

labourers, the condition of the independent class is depressed; their industry is

impaired, their employment becomes unsteady, and its remuneration in wages

are diminished. Such persons, therefore, are under the strongest inducements to

quit the less eligible class of labourers and enter the more eligible class of

paupers. . . . Every penny bestowed, that tends to render the condition of the

pauper more eligible than that of the independent labourer, is a bounty on

indolence and vice. (1834: 228)

In order to achieve less eligibility, the report recommended that, "except

as to medical attendance," relief should be granted to able-bodied labor-

ers and their families only in well-regulated workhouses (1834: 262).

The elimination of outdoor relief would not only eliminate unemploy-

ment, it would also cause laborers to become "more steady and dili-

gent," thereby increasing productivity, which would make "the return to

the farmers' capital larger, and the consequent increase of the [wages]

fund for the employment of labour enables and induces the capitalist to

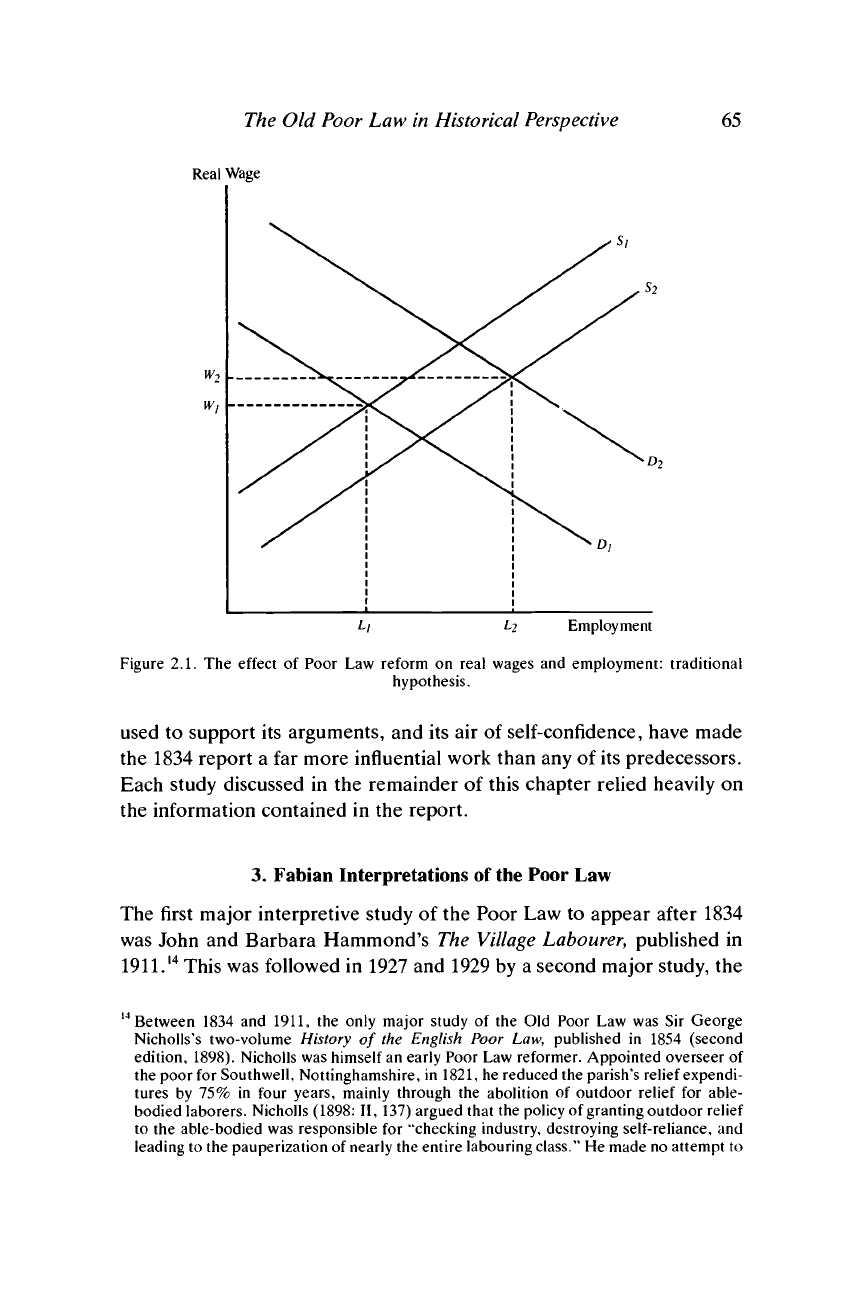

give better wages" (1834: 329). A graphical representation of the re-

port's hypotheses concerning the effects of Poor Law reform on wage

rates and employment is given in Figure

2.1.

The report maintained that

the elimination of outdoor relief would cause a rightward shift in the

supply curve of agricultural labor from S, to 5

2

, and a rightward shift in

the demand curve from D

x

to D

2

, owing to the increase in labor's produc-

tivity, so as to cause both the equilibrium wage rate and the employment

of labor to increase.

The Report of the Royal Poor Law Commission is by far the most

influential work ever written on the economic effects of the Old Poor

Law. Ironically, most of the report's arguments in favor of the abolition

of outdoor relief were not original. But the massive amount of evidence

The Old Poor Law in

Historical Perspective

Real Wage

65

Employment

Figure 2.1. The effect of Poor Law reform on real wages and employment: traditional

hypothesis.

used to support its arguments, and its air of self-confidence, have made

the 1834 report a far more influential work than any of its predecessors.

Each study discussed in the remainder of this chapter relied heavily on

the information contained in the report.

3.

Fabian Interpretations of

the

Poor Law

The first major interpretive study of the Poor Law to appear after 1834

was John and Barbara Hammond's The

Village

Labourer, published in

1911.

14

This was followed in 1927 and 1929 by a second major study, the

14

Between 1834 and 1911, the only major study of the Old Poor Law was Sir George

Nicholas two-volume History of the English Poor Law, published in 1854 (second

edition, 1898). Nicholls was himself an early Poor Law reformer. Appointed overseer of

the poor for Southwell, Nottinghamshire, in

1821,

he reduced the parish's relief expendi-

tures by 75% in four years, mainly through the abolition of outdoor relief for able-

bodied laborers. Nicholls

(1898:

II, 137) argued that the policy of granting outdoor relief

to the able-bodied was responsible for "checking industry, destroying self-reliance, and

leading to the pauperization of nearly the entire labouring

class."

He made no attempt to

66 An Economic History of

the

English Poor Law

seventh and eighth volumes of Sidney and Beatrice Webb's English

Local Government.

l

* Volume seven was devoted to the Poor Law from

the 1590s to 1834, and volume eight contained a detailed analysis of the

1834 Poor Law Report. These two works, similar in tone, comple-

mented each other in their analysis of the Poor Law during the

Speenhamland era. Together, they form what has been called "the clas-

sic Fabian interpretation" of the Poor Law.

Although the analysis of the Poor Law contained in The Village La-

bourer accepted many of the conclusions reached by the 1834 report, the

Hammonds argued that the provision of outdoor relief for able-bodied

laborers (in their words, the Speenhamland system) was not an exoge-

nous event but rather an endogenous reponse to changing economic con-

ditions in rural areas. Like Davies, the Hammonds argued that the

Speenhamland system was adopted to deal with "the collapse of the eco-

nomic position of the laborer." The collapse was mainly caused by the

enclosure movement that began in the 1760s but was brought to a head by

the "exceptional scarcity" of 1795 (Hammond and Hammond 1913: 120).

The effect of

the

enclosure movement was to destroy the economic basis

of agricultural laborers' independence. The Hammonds contended that

in

an

unenclosed village,

. . . the

normal labourer

did not

depend

on his

wages

alone.

His

livelihood

was

made

up

from various sources.

His

firing

he

took from

the waste,

he had a cow or a pig

wandering

on the

common pasture, perhaps

he

raised

a

little crop

on a

strip

in the

common fields.

He was not

merely

a

wage

earner

... he

received wages

as a

labourer,

but in

part

he

maintained himself

as

a producer.

... In an

enclosed village

at the end of the

eighteenth century

the

position

of the

agricultural labourer

was

very different.

All his

auxiliary

re-

sources

had

been taken from

him, and he was now a

wage labourer

and

nothing

more. Enclosure

had

robbed

him of the

strip that

he

tilled,

of the cow

that

he

kept

on the

village pasture,

of the

fuel that

he

picked

up in the

woods,

and of the

turf that

he

tore from

the

common.

(1913:

106)

determine

the

reasons why

the

system

of

outdoor relief had been adopted,

or

why

it had

survived

for

more than

40

years.

His

analysis

of the

economics

of

outdoor relief

was

essentially

a

repeat

of the

analysis presented

in the 1834

Poor

Law

Report.

For

this

reason, Nicholls's

History

cannot

be

considered

an

important contribution

to

the histori-

ography

of

the

Old

Poor Law.

13

Two other studies published

at

about

the

same time

as The

Village Labourer

provided

analyses

of the Old

Poor

Law: W.

Hasbacrf s History

of

the English Agricultural

La-

bourer

(1908:

171-216);

and

Lord Ernie's

English Farming Past and Present

(1912:

303-

31;

431-8). Hasbach

and

Ernie reached conclusions similar

to

those

of

the Hammonds.

They maintained that

the

system

of

outdoor relief was adopted

in

response

to

changing

economic conditions;

in

particular,

the

enclosure

of

commons

and

waste

and the

decline

in real wage rates. Like

the

Hammonds, they concluded that

the use of

outdoor relief

had disastrous consequences

for

rural parishes.