Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ing excavations to the southwest of the hillfort in

1999.

Unsystematic explorations of mounds within 5

kilometers of the hillfort are recorded as early as the

sixteenth century, peaking in the nineteenth centu-

ry following Paulus’s excavations. Looting com-

bined with the gradual destruction by plowing of

mounds on arable land has taken its toll on the Early

Iron Age burial monuments in this area. Roughly

130 burial mounds, also referred to as tumuli, were

known in the Heuneburg area by the end of the

1990s. This probably represents only 10 percent of

the original total.

The first exploratory trenching of the hillfort

took place in 1921, establishing the contemporane-

ity of the settlement and the tumuli roughly 400

meters north-northwest of the promontory fort in-

vestigated by Paulus. Beginning in 1950, twenty-

nine years of systematic fieldwork on the acropolis,

led by Wolfgang Kimmig and Egon Gersbach, un-

covered a fortification system of air-dried, white-

washed mud bricks on a limestone foundation. This

arid-climate construction technique is not found on

any other temperate European Iron Age site. Far

from being especially vulnerable to the wet climate

of the region, it actually survived longer than the

homegrown wood-and-earth fortification systems

that came before and after it. Though relatively fire-

resistant, the mud-brick wall was ultimately leveled

following a major fire around 540

B.C. that de-

stroyed a significant portion of the hillfort and outer

settlement. Additional evidence for contact with the

Mediterranean world of the sixth century

B.C. was

recovered in the form of distinctive Greek imported

pottery known as black figure ware, as well as trade

amphorae that were probably used to transport

wine and olive oil. These imports, combined with

the ostentatious wealth of the burial mounds near

the hillfort, are the hallmarks of a so-called Fürsten-

sitz, or “princely seat.” The Heuneburg is one of a

small number of such sites in the so-called West

Hallstatt Zone (southwest Germany, eastern

France, Switzerland north of the Alps).

By 1979, when excavation yielded to analysis

and publication of features and finds, just over a

third of the plateau had been explored. The site was

occupied from the Late Neolithic (fourth and third

millennia

B.C.) until the medieval period (eleventh

and twelfth centuries). Altogether twenty-three

separate building phases were identified. The earli-

est fortification of the plateau dates to the end of the

Early Bronze Age to the beginning of the Middle

Bronze Age (seventeenth century

B.C.). Through-

out the thirteenth and twelfth centuries

B.C. the site

seems to have controlled the economic, social, and

religious life of a local microregion. Beginning in

1999, the discovery by Siegfried Kurz of several

small settlements in the Heuneburg hinterland dat-

ing to this period support this hypothesis of a two-

tiered settlement hierarchy for the Bronze Age

Heuneburg region.

Population estimates for the Early Iron Age site

complex (plateau, outer settlement, associated buri-

al mounds) are complicated by the fact that the

outer settlement, which in 2003 was still being ex-

plored, and the plateau itself have not been com-

pletely excavated. However, the site appears to have

housed several thousand people at its peak during

the Late Hallstatt–Early La Tène period (seventh to

fifth centuries

B.C.). Based on the known size of the

settlement complex, the evidence for long-distance

exchange and the wealth of the surrounding burial

mounds, the Heuneburg during its Early Iron Age

heyday is interpreted as a central place controlling

a large region characterized by a multitiered settle-

ment hierarchy composed of at least three settle-

ment-size categories. The hillfort’s strategic posi-

tion on the Danube, its proximity to iron ore

resources, the evidence for various kinds of produc-

tion activity (especially metalworking and textile

production) on a scale consistent with an export

trade system, and the size of some of the multi-

roomed structures at the site all testify to the socio-

political and economic importance of the Heune-

burg during this period.

The Iron Age burial mounds associated with

the Heuneburg echo the social complexity and eco-

nomic dominance suggested by the settlement re-

cord. Following Paulus’s excavations in the mounds

near the hillfort, no systematic explorations were

conducted until Gustav Riek’s partial excavation in

1937–1938 of the Hohmichele—at 13.5 meters

high and with a diameter of 85 meters, the second-

largest known Early Iron Age burial mound in Eu-

rope (fig. 1). Although the central chamber had

been looted, seven inhumations (body burials) were

recovered, including an intact chamber grave

(Grave VI) containing the inhumations of a man

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

250

ANCIENT EUROPE

and a woman buried with a four-wheeled wagon,

bronze drinking vessels, personal ornaments (for

both individuals), and weapons (a dagger, a quiver

full of iron-tipped arrows, and a bow with the male

individual).

Beginning in 1999, excavations by the author

and colleagues in two smaller mounds (Tumulus 17

and Tumulus 18) 200 meters from the Hohmichele

produced twenty-three new burials. Tumulus 17

Grave 1 contained a bronze cauldron, an iron short

sword, two iron spear points, an iron belt hook, and

a helmet plume clamp, whereas Tumulus 18, exca-

vated in 2002, produced two burials with bronze

neckrings, a costume element that was a marker of

elite status in Iron Age Europe until well into the

Christian period in Ireland and Scotland. The ongo-

ing search for supporting, smaller settlements in the

Heuneburg hinterland (by Siegfried Kurz), the ef-

forts to delineate the boundaries of the outer settle-

ment (by Hartmann Reim), and the systematic ex-

Fig. 1. The Heuneburg situated on a hill in the Upper Danube Valley. © ERIC LESSING/ART RESOURCE, NY. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

cavation of additional burial mounds (by Bettina

Arnold and colleagues) are beginning to fill in the

picture scholars have constructed of this dynamic

Early Iron Age center.

See also Hillforts (vol. 2, part 6); Greek Colonies in the

West (vol. 2, part 6); Iron Age Germany (vol. 2,

part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnold, Bettina. “The Material Culture of Social Structure:

Rank and Status In Early Iron Age Europe.” In Celtic

Chiefdom, Celtic State: The Evolution of Complex Social

Systems in Prehistoric Europe. Edited by Bettina Arnold

and D. Blair Gibson, pp. 43–52. Cambridge, U.K.:

Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Arnold, Bettina, and Matthew L. Murray. “A Landscape of

Ancestors in Southwest Germany.” Antiquity 76, no.

292 (2002): 321–322. (Additional information is avail-

able from the website “A Landscape of Ancestors: The

Heuneburg Archaeological Project” at http://

www.uwm.edu/~barnold/arch/.)

THE HEUNEBURG

ANCIENT EUROPE

251

Bittel, Kurt, Wolfgang Kimmig, and Siegwalt Schiek. Die

Kelten in Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart, Germany:

Theiss, 1981.

Kimmig, Wolfgang. Die Heuneburg an der oberen Donau.

Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Baden-

Württemberg 1. Stuttgart, Germany: Theiss, 1983.

Kurz, Siegfried. “Siedlungsforschungen bei der Heuneburg,

Gde. Herbertingen-Hundersingen, Kreis Sigmarin-

gen—Zum Stand des DFG-Projektes.” In Archäolog-

ische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2001, pp.

61–63. Stuttgart, Germany: Theiss, 2002.

Reim, Hartmann. “Siedlungsgrabungen im Vorfeld der

Heuneburg bei Hundersingen, Gde. Herbertingen,

Kreis Sigmaringen.” In Archäologische Ausgrabungen in

Baden-Württemberg 1999, pp. 53–57. Stuttgart, Ger-

many: Theiss, 2000.

Rieckhoff, Sabine, and Jörg Biel. Die Kelten in Deutschland.

Stuttgart, Germany: Theiss, 2001.

B

ETTINA ARNOLD

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

252

ANCIENT EUROPE

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

IBERIA IN THE IRON AGE

■

As in other areas of the Mediterranean, the classic

European division of the Iron Age into the Hallstatt

and La Tène phases is not applicable to the Iberian

Peninsula. During the first millennium

B.C. this area

underwent intense change in which different cul-

tures interacted. The local traditions of the Bronze

Age came to an end, and new populations became

established. Some of them were of Continental ori-

gin, for example, those of the Urnfield culture, the

last traces of which are seen in the seventh century

B.C. Of greater impact, however, were those of the

Mediterranean, beginning with the Phoenicians,

who founded their first colonies along the southern

coast at the end of the ninth century

B.C. The cul-

tural characteristics of the Iberian Peninsula, with its

Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Continental influ-

ences as well as its local traditions, made the Iron

Age a time of complex change that showed little

chronological homogeneity. The general features

that developed over the long term included the de-

finitive settlement of populations, the marking of

political territories, the intensification of agriculture

through the introduction of iron tools, the progres-

sive development of social hierarchy, and accompa-

nying ideological changes.

THE ORIGINS OF IRON AGE IBERIA

The arrival of the Phoenicians and the founding of

several coastal colonies and trading ports were

among the factors that marked the beginning of the

Iron Age on the Iberian Peninsula. Important trans-

formations occurred in the economics of the area,

accompanied by changes in the political, religious,

and social spheres. The Phoenician colonies, among

which Gadir (now Cádiz) stands out, assured their

subsistence by marking out large catchment areas as

well as developing fishing and fish-salting industries.

Specialized crafts were developed that introduced

new techniques to goldsmithing, the forging of

iron, and the making of wheel-turned pottery. In

addition to introducing such exotic objects as ivory,

alabaster jars, and ostrich eggs, these colonies are at-

tributed with introducing new domestic fauna, such

as asses and chickens; expanding wine consumption;

and generally incorporating much of the peninsula

into the political and commercial dynamics of the

Mediterranean.

The economic factors of the Phoenician cities in

the Near East were important in the election of the

Iberian territories for colonization. The Ríotinto

mines in the southwest (Huelva) were considered

fundamental to the supply of silver to Tyrus (mod-

ern-day Tyre) and Sidon. They would allow com-

mercial strength to be maintained while meeting

the increasing tax demands of Assyria. The richness

of these mining areas, which were developed in an

open-cast fashion, must have been evident to Phoe-

nician metallurgists, because the Huelva mines pro-

duced some 2,000 grams per ton of silver and 70

grams per ton of gold.

The mines of the southeast, located around

what eventually would become the Carthaginian

cities of Baria (present-day Viaricos) and Cartago

Nova (present-day Cartagena), also were exploited.

The lead ingots obtained in this way were transport-

ed by small boats that hugged the coast until they

reached the main ports. The seventh-century wreck

ANCIENT EUROPE

253

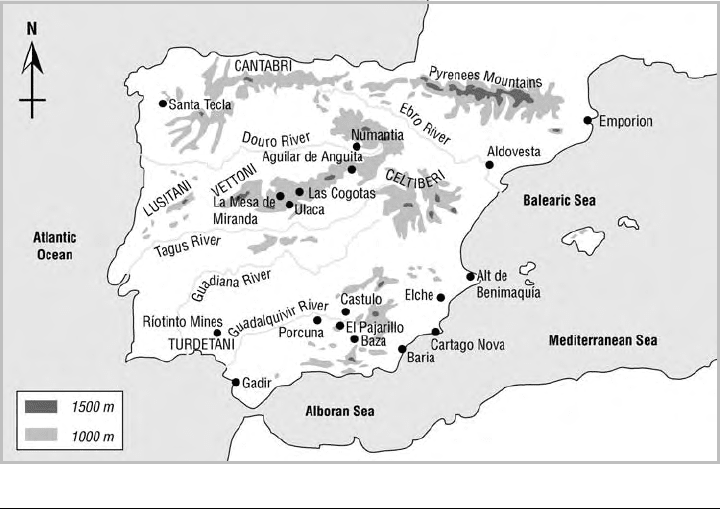

Selected sites and selected populi of Iron Age Iberia.

of one Phoenician vessel at Mazarrón, which has

been preserved in excellent condition, was carrying

2,000 kilograms of lead oxide when it sank. The in-

tense mining activity, which reached its peak in the

seventh century

B.C., caused notable deforestation

and the release of important contaminants, as re-

vealed by ice layers in Greenland that correspond to

this time.

All this activity implied great change for the in-

digenous population, which not only saw how part

of its territory was progressively occupied but also

must have supplied the greater part of the workforce

for the mines. The southwest of the peninsula, the

hinterland of this colonial world, experienced the

upsurge of the “Tartessian culture,” which became

a mythical reference among the legends of the ex-

treme western Mediterranean. The people of the in-

terior, even those far from the coast, became suppli-

ers of the raw materials required by the Phoenicians

as well as a market for the products that the colo-

nists manufactured. Enclaves on the estuaries and

along the courses of the main rivers show that Phoe-

nician trade sought out these inland areas. Those on

the Sado and Mondego Rivers in western Portugal

and on the Aldovesta in the northeast of the penin-

sula reveal how Phoenician commerce tried to make

use of the infrastructure and penetration routes

controlled by native populations.

This entire process had a strong ideological im-

pact, which is detectable through the religious

changes that took place on the southern and eastern

parts of the Iberian Peninsula. Phoenician sanctu-

aries, such as that of Melkart in Gadir, also were

built at the former mouth of the Guadalquivir

(Roman Baetis), near Seville. There a sanctuary

dedicated to Astarte (Spanish Ashtarte), goddess of

fertility and sexual love, was erected, from which a

beautiful bronze statuette with a dedication has

been recovered. Many other Phoenician divinities

were adapted to the religious beliefs of the indige-

nous populations of the Tartessian area, as evi-

denced by the palace sanctuary of Cancho Roano in

Extremadura. The iconography of the goddess As-

tarte was absorbed as a representation of the mother

goddess venerated over a large part of Iberia. This

is palpable proof of the profound political and eco-

nomic transformations ushered in by the Phoeni-

cians.

The first Greek explorations also made contact

with the Tartessian world of the far west. Herodotus

(book 1 of the Inquiries) indicates that the mythical

Tartesian king Arganthonius established good rela-

tions with the Phocaeans, to the point that Tartes-

sian silver was used to finance the building of a

strong stone wall to protect Phocaea. These con-

tacts have led some authors to establish Tartessus as

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

254

ANCIENT EUROPE

the site of one of the twelve tasks of Hercules: his

fight with the monster Geryon and his dog Orthros,

both of whom were killed by the hero, who took

from them the herd of red cows he later delivered

to Greece.

BIRTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE

IBERIAN CULTURE

When Phoenician commercial dominance went into

crisis at the start of the sixth century

B.C., Carthage

gained control of the colonial southern peninsula,

and some relevant places, such as Gadir, developed

as totally independent centers. This same point in

time also saw the appearance of certain culturally

identifiable groups, such as the Iberians, whose ter-

ritories extended from southeastern France down to

the old Tartessian kingdom (which at this time was

given the name Turdetania). The Iberian popula-

tions were divided into different political units (the

Ilergetes, Lacetani, Edetani, Contestani, Bastetani,

and Oretani, among others), in whose territories

some very large settlements existed. Stone walls re-

inforced with towers fortified their towns, and

houses of one or two floors lined their stone streets.

In eastern Andalusia a system of concentrating the

population seems to have existed in the catchment

area dominated by the oppida. In other locations,

such as Valencia, rural settlements abounded next

to worked fields. Economic territories revolved

around river valleys, religious centers playing an im-

portant role in their symbolic definition. This ap-

pears to be a case very similar to that described by

François de Polignac, the Greek scholar, for the

Greek world, as can be appreciated in the iconogra-

phy of the Iberian sanctuary of El Pajarillo de Huel-

ma and in the large group of sculptures at Porcuna,

both in the province of Jaén.

The cultural substratum of the Iberians was in-

fluenced strongly by local and Phoenician tradi-

tions, but their commercial contacts were with the

Greek colonies of the western Mediterranean. Em-

porion, a Phocaean foundation linked to Massalia as

well as to other towns, such as Alonis or Akra Leuke

(which have not been located but are cited in texts),

was a point at which goods were loaded and Greek

pottery, wine, and oil (products highly valued on

the Iberian Peninsula) were unloaded. Some trad-

ing treaties, such as that of Ampurias, belonging to

the second half of the sixth century

B.C., were in-

scribed on lead. This particular treaty accords the

shipment of goods from the port of Sagunto. The

relationship between Greeks and Iberians was very

close, as is seen in the southeast of the peninsula,

where a Greco-Iberian language developed, which

expressed the local tongue in Ionian characters.

An important economic as well as cultural trans-

formation was the production and consumption of

wine. Amphorae of varying Mediterranean prove-

nances have been recovered at the Iberian settle-

ments, but there are signs of developed local pro-

duction at least from the sixth century

B.C. onward.

At the fortified settlement of Alt de Benimaquía

(Valencia), several pools were dedicated to the

treading of grapes, and the wine obtained was

stored in amphorae of Phoenician typology. Much

of the Greek pottery found on settlements and cem-

eteries from the fifth century on were linked precise-

ly with the consumption of wine.

After the end of the fifth century

B.C., iron tools

began to be used in agriculture. This had the effect

of intensifying production, which was linked to an

increase in the population and in commerce. Calcu-

lations of the capacity of the numerous cereal stor-

age pits documented for the area of Emporion in

the northeast of Catalonia show it to have greatly

exceeded the needs of the local people. Therefore

a large part of the stored grain probably was des-

tined for export. In addition the Castulo silver

mines in Oretani territory assured the profit of

commercial activities. Findings of Attic pottery

along the old routes connecting the ports with this

city are witness to the intensity of these economic

relations.

The social organization of the Iberian peoples

has been investigated through the study of their vil-

lages and corresponding necropolises. These sites

reveal the existence of a warrior aristocracy that al-

ways cremated its dead before burying them in

tombs. Some of these groups constructed towers or

stelae with sculptural decoration playing an impor-

tant role. Real animals (lions, bulls, and horses) and

mythical creatures (sphinxes and griffins) were pre-

ferred by Iberian sculptors for the protection of the

tombs of important people. Greek and oriental in-

fluences can be seen in these decorations.

Among the funerary equipment that accompa-

nied the urns holding the cremated bones, Greek

IBERIA IN THE IRON AGE

ANCIENT EUROPE

255

ceramics (kraterae [jars for mixing wine and water],

kylix [wine cups], and skiphoi [cups]) stand out.

These items were highly valued for their quality,

their shiny varnish, and their iconography and

sometimes were imitated by local craftspeople. Ibe-

rian ceramics, with their orange hues and red-

painted geometric decorations, also were the prod-

ucts of specialized craftspeople. In some areas of the

east and southeast figurative themes were devel-

oped, with scenes of human activity as well as animal

and plant motifs. Iron weapons were important as

well, especially the falcata, an original curved sword

the shape of which has been likened to the Greek

machaira and which demonstrated mastery of a re-

fined technology.

Iberian religion was of the Mediterranean type.

Among the major systems was the veneration of a

certain goddess, protector of life and death. She was

represented through outstanding sculptures, such

as the well-known Dama de Elche or the Dama de

Baza, a large stone statue representing a veiled

woman sitting on a winged throne, within which

were ashes and cremated bones. These pieces are

testimony to the rich clothing worn by Iberian

women and the numerous articles of jewelry used

on special occasions. Nevertheless those objects typ-

ically were not deposited within the grave, suggest-

ing the existence of hereditary transmission systems.

The members of these societies are represented in

the thousands of stone and bronze votive offerings

that have been found in sanctuaries both in rural

settings and at the entrance to settlements. Caves in

mountainous areas of difficult access were special

places of devotion, which suggests a relationship to

initiation rites.

THE CENTRAL AND WESTERN AREAS

OF THE IBERIAN PENINSULA

DURING THE IRON AGE

Other peoples with different roots, normally

grouped together as Celts owing to their character-

istics and languages of Indo-European origins, oc-

cupied the central and western parts of the peninsu-

la. Outstanding among them are the Celtiberi,

Vaccei, and Vettoni and farther west the Lusitani.

The Iron Age brought about important changes in

the economic models characteristic of the western

peninsula. At the end of the Bronze Age economic

power was based on the control of livestock and

trading routes, but during the Iron Age there was

a trend toward the intensification and dominance of

agricultural production. The transition toward this

model was linked to the adoption of definitive sed-

entary settlements. Warrior groups used their new

iron weapons to gain better land.

The introduction of the plow usually is consid-

ered a step indicative of the passage from a model

of community property to one of privately owned

land. The existence of plots dividing up cultivatable

land as well as separating such land from pasture has

been proposed. Crude zoomorphic sculptures from

the Vettonian area, representing pigs and bulls

(known as verracos), are thought to have signaled

the claims of particular groups to stock-raising re-

sources, such as winter pastures. Control of the land

for agriculture, as a complement to stock raising, led

to changes in the relationship between society and

its environment, to unequal access to resources, and

to progressive social differentiation.

Vettonian settlements were of two basic types,

larger ones acting as central hubs and smaller ones

basically concerned with agricultural production.

Among the former, Ulaca (60 hectares), Las Co-

gotas (14.5 hectares), and La Mesa de Miranda (30

hectares in maximum extent) stand out, all oppida.

Vettonian settlements had strong fortifications and

dispersed domestic units. The interior of these

enormous settlements included not only houses but

also centers of worship and sacrificial altars, live-

stock pens, marketplaces, neighborhoods of artisans

with their kilns and metallurgical furnaces, and even

quarries. They were so big and their activities so di-

verse that part of the population might never have

needed to leave them in their daily lives. Popula-

tion-density calculations, based on the number of

tombs recovered from the necropolises associated

with these settlements, show low values.

At Las Cogotas there are four differentiated

areas of graves and nearly 1,500 cremation burials,

but because the cemetery was used for a long period

of time, not more than 250 people are thought to

have lived in this large hillfort at any given time. The

existence of separate funerary areas seems to reflect

a system of lineal descent in kinship groups whose

economy was based on control of different re-

sources, without a remarkable potential of accumu-

lation. Only 15 percent of the burials showed evi-

dence of grave goods, among which 18 percent

included such weapons as spears, shields, knives,

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

256

ANCIENT EUROPE

and swords decorated with silver as well as horse

trappings. Most of the dead are accompanied only

by pottery vessels, while women might wear spindle

whorls, finger rings, and brooches.

Smaller centers show clear differences with the

oppida. They were open sites placed on the lower

parts of the valleys and seem to be small villages or

hamlets involved in agriculture, with limited craft

production at a familiar level. These farming units

complemented stock raising, which was concentrat-

ed on the highlands and mountains.

Farther west the Lusitani (to the north of the

Tagus River), the Celtici (in the Alentejo), and the

Conii (in the Algarve) occupied most of Portugal.

A tribal organization dominated the interior areas,

the Atlantic coast developing an urban organization

more rapidly. Greek products arrived via this route,

as witnessed by the necropolis at Alcacer do Sal, al-

though this site also contains clearly western arti-

facts, such as antenna-hilt swords and printed pot-

tery. Stone walls encircle the settlements, and

domestic buildings have circular plans, built with a

stone basement and a wooden roof, the floors being

thinly paved. No evidence of ironworking is present

here until the second half of the first millennium

B.C.

The northeast of the Spanish meseta was occu-

pied by Celtiberians, who were known, among

other things, for their language, which was un-

doubtedly of Celtic origin. Both their settlements

and necropolises suggest that they formed a variety

of communities, from small hamlets of five or six

houses to villages of twenty-five to thirty domestic

units. More exceptional were large settlements with

a necropolis like that of Aguilar de Anguita, which

had a population of some 400 or perhaps even 600

people. Their characteristic settlement was the hill-

fort, a permanent village protected by a wall and

sometimes by moats and chevaux-de-frise (irregular

barriers about 50 to 80 centimeters high made up

of stones that surround the easiest access to the vil-

lages), reflecting Celtic influence. In the interior

lived a few families who survived on what the sur-

roundings produced. These self-sufficient units oc-

cupied more and more land by a system of segmen-

tation, the “overspill” of the population of one

hillfort founding another of the same type in a

neighboring area. By the end of the first millennium

B.C. the growth of some centers outweighed others

to become “capitals” occupying large extensions of

terrain, such as Numantia, which was of extraordi-

nary political importance during the clash with

Roman forces.

Celtiberian houses used the defensive wall as

their own back wall, and their homogeneity speaks

of a society with few social differences. The social

model in most of Celtic Hispania was that of warlike

tribes, authority resting with the heads of lineages

and families. This structure generally prevented any

process leading to marked inequality, as witnessed

by their housing and the egalitarian nature of most

of their burial grounds. The presence of the Ro-

mans, however, changed both their political and

economic points of reference, with the larger cen-

ters starting to become specialized in certain types

of work. For the rural hillforts, which became the

suppliers of these emerging urban nuclei, this gen-

erated a situation of inequality.

Economically the Celtiberians possessed only a

limited agriculture, which took advantage of fertile

valley bottoms. The main crops were cereals, al-

though the remains found in their villages show that

they consumed large quantities of forest products,

especially acorns. Their main activity was stock rais-

ing, especially goats and sheep, and they must have

practiced transhumance to take advantage of better

pastures at different times of the year. It has been

suggested that these groups performed the same

tasks for neighboring populations, such as the Iberi-

ans of the east.

Compared with the Mediterranean area, the

west of the peninsula appears to have maintained re-

ligious beliefs very similar to those of the Indo-

European world, worshipping such divinities as En-

dovellicus, god of health and sometimes of the

night, and Ataecina, goddess of agrarian fertility,

death, and resurrection. The greater part of these

religious forces resided in elements of nature, such

as woods, rocks, springs, or rivers. Altars, where ani-

mal sacrifices, especially of bulls, pigs, and sheep,

were made and where young warriors underwent

complex initiation ceremonies, have been preserved

both inside and outside settlements.

THE GALICIAN NORTHWEST AND

THE CANTABRIAN COAST

The northwest, which includes the north of Portu-

gal and the present Spanish region of Galicia, is

IBERIA IN THE IRON AGE

ANCIENT EUROPE

257

separated from the meseta and is of difficult and

mountainous access. During the Iron Age its devel-

opment enjoyed a great deal of autonomy. Walled

settlements, known as “Galician castra,” are its

most characteristic element. Small in size (0.5–3

hectares), they were situated where they dominated

valley areas, their interest being the control of agri-

cultural regions. Unlike anything in the rest of the

peninsula, the dwellings they contained were

round. Hardly any signs of urban organization can

be found beyond the siting of buildings to favor the

movement of people and the evacuation of the

abundant rain that falls in this area.

These castra of the pre-Roman era concentrat-

ed families with their own systems of subsistence.

No superstructure broke this organization of associ-

ated units in which sex and age were the main fac-

tors ordering social behavior. The construction and

contents of these domestic units show practically no

specialization; all incorporate the same basic func-

tional elements. The independence of each family

group was limited by the castra boundary—the only

thing that joined together these poorly united

family-autonomous communities.

Roman interests accelerated a substantial

change of this simple model. In contrast to the ar-

rangement described earlier, at the end of the Iron

Age there was a clear tendency toward intensifica-

tion and product specialization, which terminated

the autarchy of traditional systems. Agriculture and

sheep raising, and in many areas the creation of new

castra linked to mining activities aimed at the

Roman market, were factors that provoked notable

transformations. Very often the land was redistrib-

uted according to Roman interests. Some types of

land exploitation, such as gold mines, attained in-

dustrial levels of activity. This change opened the

way for hitherto unknown social differentiation.

Ideological and functional changes accompa-

nied this new situation. Large nuclei of up to 20

hectares appeared, such as that of Santa Tecla (Pon-

tevedra), leading to a considerable concentration of

the population. Their dwellings were more com-

plex, incorporating entrance halls and vestibules as

well as sets of rooms arranged around a central

patio. Decorative elements appeared in an architec-

ture whose complexity grew—and not simply with

respect to housing. The system of defensive walls

became a symbol defining both the inside and out-

side of these castra. Finally, the first cemeteries ap-

peared, with graves using stelae of Roman formula.

This movement toward complexity and social in-

equality that had visited other areas of the peninsula

in earlier times reached Galicia only now, bringing

it into line, if still incipiently, with the general model

followed throughout Iberia (although this model

did show variations).

Along the rest of the Cantabrian strip the center

and west had settlements similar to those of the me-

seta region and Galicia, respectively, with their

castra and associated farming areas. Archaeological

evidence from the Basque country is very limited.

Some of the most characteristic structures are enclo-

sures bound by stones, whose value began to be ap-

preciated for the hierarchical control of geographi-

cal and productive areas linked to rivers or streams.

The difficult mountainous terrain of these lands and

their scant economic potential favored a certain iso-

lation, appreciable even in the twenty-first century

in the area’s pre-Indo-European language.

Although this was still an eminently pastoral so-

ciety, agriculture continued to gain importance in

this period, helped by the manufacture and use of

iron tools. It was less noticeable than in other areas,

but again it illustrates the changes that led to a reor-

ganization of productive forces, developments un-

doubtedly accompanied by social adjustment.

THE END OF THE IBERIAN

IRON AGE

The Iberian Peninsula was the setting of the Second

Punic War between Rome and Carthage (218–202

B.C.). Nearly all the peninsula had come under

Punic control after the second treaty between the

two powers in 348

B.C. The foundation of New Car-

thage by the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal was

the start of a new policy of territorial domination

that looked to local aristocracies for support. Both

Hasdrubal and his brother Hannibal married Iberi-

an princesses and were recognized as leaders by the

local populations. The growing power of Carthage

threatened Roman supremacy. Many of the con-

frontations between the two powers took place on

the peninsula, complicated by fighting, which surely

occurred with indigenous groups.

The activity of these two great armies led to the

payment of soldiers with coinage, making the domi-

nation of mining areas vital. From the point of view

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

258

ANCIENT EUROPE

of the Iberian peoples, this situation provoked a mil-

itarization of human resources and a return of war-

rior chiefdoms. Men of the Iberian and Celtic areas

were used to form part of Mediterranean armies. By

the end of the sixth century

B.C. they already had

served as mercenaries of Carthage, and on other oc-

casions during the fifth and sixth centuries

B.C. they

served with both Carthaginian and Greek troops at

Syracuse. At the end of the Iron Age many of these

populations were active as troops in the Carthagin-

ian or the Roman armies, and they also could fight

as independent forces when their territory was

threatened.

After defeating Carthage in the third century

B.C., Rome installed itself first in the Iberian and

Turdetanian areas before conquering the rest of the

territory. Local resistance was fierce where the exist-

ing social structures were incompatible with the

Roman state model. A little later, however, the en-

tire peninsula entered a new phase as part of the

Roman administration, drawing the Iron Age to a

close.

See also The Mesolithic of Iberia (vol. 1, part 2); Late

Neolithic/Copper Age Iberia (vol. 1, part 4); El

Argar and Related Bronze Age Cultures of the

Iberian Peninsula (vol. 2, part 5); Early Medieval

Iberia (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Almagro Gorbea, M., and G. Ruiz Zapatero, eds. Paleoet-

nología de la Península Ibérica. Complutum 2–3. Ma-

drid: Universidad Complutense, 1992.

Aubet, María Eugenia. The Phoenicians and the West: Poli-

tics, Colonies, and Trade. Translated by Mary Turton.

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Belén Deamos, M., and T. Chapa Brunet. La Edad del Hier-

ro. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis, 1997.

Cabrera Bonet, Paloma, and Carmen Sánchez, eds. Los Grie-

gos en España: Tras las huellas de Heracles. Madrid: Min-

isterio de Educación y Cultura, 2000.

Cunliffe, Barry, and Simon Keay, eds. Social Complexity and

the Development of Towns in Iberia: From the Copper

Age to the Second Century

AD. Proceedings of the British

Academy, no. 86. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1995.

Dominguez Monedero, Adolfo J. Los Griegos en la Penínsu-

la Ibérica. Madrid: Arco Libros, 1996.

Ruiz, Arturo, and Manuel Molinos. The Archaeology of the

Iberians. Translated by Mary Turton. Cambridge, U.K.:

Cambridge University Press, 1998.

T

ERESA CHAPA

IBERIA IN THE IRON AGE

ANCIENT EUROPE

259