Baggott J. The Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the quantum story

180

Because the procedure had greatly reduced the rate of divergence even

in the non-relativistic case, he was able to make an intelligent guess and

impose a relativistic limit for the divergence. He was thus able to obtain

a theoretical estimate for the Lamb shift. He obtained a result just four

per cent larger than the experimental value that Lamb had reported.

Oppenheimer had been right. The shift was a purely quantum electro-

dynamic effect.

In great excitement, Bethe called his Cornell colleague Feynman from

Schenectady to tell him what he had discovered. On his return to Cornell

at the beginning of July, Bethe gave a lecture on the calculation and specu-

lated on ways in which a more formal relativistic limit could be applied.

After the lecture, Feynman came up to him. ‘I can do that for you,’ he

said, ‘I’ll bring it in for you tomorrow.’

181

But Feynman was unable to produce an answer for Bethe the next day. There were still

some things about the calculations that Feynman had to learn in order to apply his path-

integral approach. He learned quickly.

Schwinger learned quickly too, as the New York physicists became rivals in the race

to build a relativistic QED that could be renormalized. The Lamb shift could be almost

explained using a non-relativistic approach, as Bethe had demonstrated, but the g-factor

anomaly would require a fully relativistic theory. ‘The magnetic moment of the electron,’

Schwinger explained, ‘which came from Dirac’s relativistic theory, was something that

no non-relativistic theory could describe correctly. It was a fundamentally relativistic

phenomenon. . .’

Where Schwinger was logical and conventional, rigorously plodding through the terms

in the perturbation expansion, Feynman was intuitive, vigorously ploughing through the

mathematics using little more than inspired guesswork. He was ready to reach for bizarre

methods, if needed. When faced with a particularly stubborn problem in his analysis of

the situation where a fi eld produces an electron–positron pair which then annihilate to

produce a new fi eld, he recalled a suggestion made by Wheeler. He decided to treat the

problem as if the particles could travel backwards in time.

He was still wrestling with the solution when the second in the series of small National

Academy-sponsored conferences was convened. This took place on 30 March 1948 at the

Pocono Manor Inn in the Pocono Mountains near Scranton, Pennsylvania.

19

Pictorial Semi-vision Thing

New York, January 1949

the quantum story

182

At the Pocono conference, the small gathering of physicists was looking to Schwinger

for the defi nitive answer on relativistic QED. This time both Bohr and Dirac were

present. Schwinger’s presentation, on the second day of the conference, was a virtuoso,

but marathon, fi ve-hour event. Eyes glazed over and minds became numb as Schwinger

derived one mathematical result after another. It was only when Schwinger tried to make

connections with the underlying physics that the audience came to life and asked ques-

tions. Only Fermi and Bethe, it seemed, had followed Schwinger through to the end.

In his own lecture Feynman had intended to talk primarily about the physics. He had,

after all, arrived at his mathematics largely by trial-and-error and felt that he was on

shaky ground. But Bethe now advised him: ‘You should better explain things mathemati-

cally and not physically, because every time Schwinger tries to talk physically he gets into

trouble.’

Feynman took Bethe’s advice and changed his approach to the lecture. He talked

mathematics. It was a disaster. The path-integral approach was entirely foreign to his

audience, and soon Dirac was asking awkward questions about the mathematics, con-

cerned about the implications of positrons travelling backwards in time. Bohr didn’t like

Feynman’s approach at all. The very idea of particle trajectories was anathema to the

Copenhagen interpretation. ‘Bohr thought that I didn’t know the uncertainty principle,

and was actually not doing quantum mechanics right either. He didn’t understand at all

what I was saying.’

When the lectures had concluded, Feynman and Schwinger got together in the hallway

and compared their results. Neither understood the other’s equations but, despite their

very different approaches, their results were identical.

‘So I knew that I wasn’t crazy,’ Feynman said.

Schwinger’s work was seen to be defi nitive, but his structure was so

unwieldy that it seemed that Schwinger was the only theorist able to use

it. However, shortly after returning to Princeton following the Pocono

conference, Oppenheimer discovered that this was not a two-horse

race, after all. Japanese theoretical physicist Sin-itiro Tomonaga was also

working on a relativistic QED, using methods similar to Schwinger but a

lot more straightforward.

Tomonaga had learned quantum physics in Japan under the guidance of

the esteemed physicist Yoshio Nishina. He graduated from Kyoto University

in 1929, together with his friend and colleague Hideki Yukawa. He remained

in Kyoto for the next three years, working as an unpaid assistant, and in 1931

pictorial semi-vision thing

183

joined Nishina’s group at the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research

in Tokyo. He became the Nishina group theorist, working on problems in

quantum physics in close collaboration with the experimentalists.

He followed developments in quantum electrodynamics through the

papers of Dirac, Heisenberg, and Pauli. In 1937 he moved to Leipzig to

work with Heisenberg on nuclear physics and quantum fi eld theory,

returning to Tokyo two years later. A paper on nuclear physics writ-

ten whilst in Leipzig became a major part of his doctoral thesis. He was

appointed to a professorship in physics at the Tokyo College of Science

and Literature in 1940.

Physics had to give way to basic survival in the aftermath of Japan’s

unconditional surrender on 14 August 1945, but Tomonaga managed to

keep a team of young physicists together and continued to work on QED.

Stimulated by reports in 1947 of Lamb’s experiments and Bethe’s non-

relativistic calculation of the Lamb shift, the Japanese physicists worked

on methods of renormalization of both the electron mass and charge.

‘The method of calculation was quite new,’ explained one of Tomonaga’s

associates. ‘We were sometimes at a loss how to calculate, since there

were many new things to be solved. At fi rst we attempted to use a rela-

tivistic covariant way of calculating in various ways, but we were always

unsuccessful. Then we decided to evaluate in a way which is similar

to conventional perturbation theory. Prof. Tomonaga also calculated

some fundamental things, and gave us many valuable suggestions. The

calculation was very tedious.’

Tomonaga sent a letter to Oppenheimer outlining the group’s results

in April 1948. Oppenheimer immediately sent copies to all the delegates

who had attended the Pocono conference. He wrote:

When I returned from the Pocono Conference, I found a letter from

Tomonaga which seemed to me of such interest to us all that I’m sending

you a copy of it. Just because we were able to hear Schwinger’s beautiful

report, we may better be able to appreciate this independent development.

Oppenheimer sent a cable to Tomonaga urging him to write a summary of

his work, for which he would arrange speedy publication in the American

journal Physical Review. The paper appeared in the 15 July issue.

the quantum story

184

The work of Tomonaga and his group in Tokyo made a favourable

impression on a young, highly creative English physicist working with

Bethe at Cornell. As Freeman Dyson later explained:

Tomonaga expressed his [version of QED] in a simple, clear language so

that anybody could understand it and Schwinger did not. When you read

Schwinger you had the impression it was immensely complicated from

the start. Tomonaga set the framework in a very beautiful way. To me that

was very important. It gave me the idea that this was after all simple.

Tomonaga’s and Schwinger’s approaches were similar, but Feynman’s was

off the wall. He had developed a very singular, appealing, and intuitive

diagrammatic way of describing and keeping track of the perturbation

corrections. These became known as Feynman diagrams.

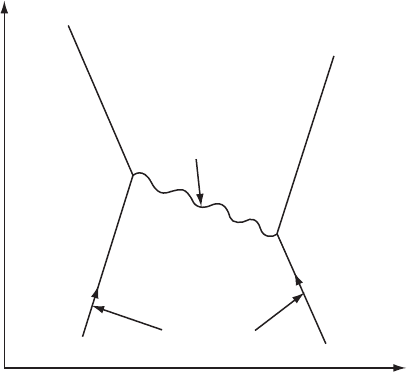

Feynman diagrams have only two axes, a vertical one for time and

a horizontal one for ‘space’, effectively projecting a three-dimensional

view of a quantum interaction to a single dimension. Feynman used the

diagrams to provide a way to visualize the interactions of quantum par-

ticles such as electrons and photons in both space and time. No wonder

it didn’t meet with Bohr’s approval.

For example, the interaction between two electrons is represented in a

Feynman diagram in terms of electron paths pictured as continuous lines,

their directions marked by arrows. As the electrons move closer to each

other, they ‘feel’ a repulsive electromagnetic force and move apart. This

force is carried by a ‘virtual’ photon as the quantum of the electromagnetic

fi eld (‘virtual’ because the photon is never visible), represented as a wavy

line connecting the electron paths at their point of closest approach.

Reading such a diagram logically, we might conclude that one electron

emits a virtual photon which is absorbed some short time later by the

second electron. However, the symmetry of the interaction is such that

there is in principle nothing to prevent us from concluding that the pho-

ton is emitted by the second electron and travels backwards in time to be

absorbed by the fi rst. The wavy line of the virtual photon therefore does

not show a direction, since both directions are possible.

The diagrams serve as a useful aid to the visualization of the process,

but Feynman intended them primarily as a book-keeping device for all

pictorial semi-vision thing

185

the different ways that the quantum particles can interact in going from

some initial state to some fi nal state. For each diagram there is a term

in the perturbation expansion containing an amplitude function which,

when its modulus is squared, gives a probability for the process as a con-

tribution to the total probability of conversion from initial to fi nal state.

Feynman’s path-integral approach demands that all the possible routes

a quantum system can take from initial to fi nal state be considered, no

matter how seemingly improbable. The most important contribution to

the interaction will be the ‘direct’ transition from initial to fi nal state, but

all the ‘indirect’ routes represent corrections to the interaction term and

have to be included as well.

Feynman later tried to explain where the diagrams had come from and

what they represented:

The diagram is really, in a certain sense, the picture that comes from trying

to clarify visualisation, which is a half-assed kind of vague [picture], mixed

with symbols. It is very diffi cult to explain, because it is not clear. . . It is

hard to believe it, but I see these things not as mathematical expressions

Time

virtual

photon

Space

electrons

fig 9 A Feynman diagram illustrating the interaction between two electrons. The

electromagnetic force of repulsion between the electrons involves the exchange of a

virtual photon at the point of closest approach.

the quantum story

186

but a mixture of a mathematical expression wrapped into and around, in a

vague way, around the object. So I see all the time visual things associated

with what I am trying to do. . . What I am really trying to do is to bring

birth and clarity, which is really a half-assedly thought out pictorial semi-

vision thing. OK?

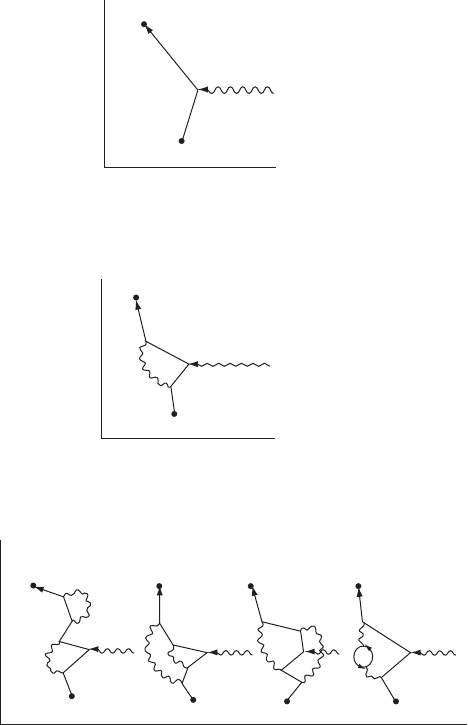

But, no matter how vague their origin, the diagrams worked. The starting

point for the evaluation of the g-factor of the electron is the interaction of

an electron with a photon from a magnet. This is the simplest, most direct

interaction involving an electron in some initial state at some initial time

and position to some fi nal state at a fi nal time and position. Evaluating

the electron magnetic moment from the interaction term represented by

this diagram gives the Dirac result, a g-factor of exactly 2.

There are other ways this process can happen, however. Within this

same interaction, a virtual photon can be emitted and absorbed by the

same electron, viewed either forwards or backwards in time. This rep-

resents an electron interacting with its own electromagnetic fi eld and,

although the probability of this occurring is small, it is not zero. Includ-

ing this term in the perturbation expansion makes the g-factor of the

electron slightly larger than 2.

Further corrections are represented by self-interaction via two virtual

photons. In a still further correction, a single virtual photon creates an

electron–positron pair which then mutually annihilate to form another

photon which is then subsequently absorbed.

Processes such as this last example seemed to imply that the rules of energy

conservation had been abandoned once again. But it had by now become

apparent that creation and destruction of virtual particles was entirely

allowed within the constraints of Heisenberg’s energy–time uncertainty

relation. The energy required to create a photon or an electron–positron

pair literally out of nothing can be ‘borrowed’ so long as it is ‘given back’

within the time frame determined by the uncertainty principle.

The probabilities of the occurrence of processes with ever-more complex

and convoluted interactions may be very small, but they nonetheless pro-

vide important corrections in the perturbation expansion. A free electron

doesn’t simply persist as a point-particle travelling along a predetermined,

classical path; it is surrounded by a swarm of virtual particles arising from

self-interactions with its own electromagnetic fi eld.

187

(a)

(b)

(c)

Time

Space

Space

Space

photon from magnet

photon from magnet

electron

electron

Time

Time

+–

fig 10 (a) Feynman diagram for the interaction of an electron with a photon

from a magnet. Considering only this interaction would lead to the prediction

of a g-factor for the electron of exactly 2, as given by Dirac’s theory. (b) The

same process as described in (a), but now including electron self-interaction,

depicted as the emission and re-absorption of a virtual photon. Including

this process leads to a slight increase in the prediction for the g-factor for

the electron. (c) Further ‘higher-order’ processes involving emission and

re-absorption of two virtual photons. The diagram on the right shows the

spontaneous creation and annihilation of an electron-positron pair. Adapted

from Richard P. Feynman, QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Penguin,

London, 1985, pp. 115–117.

the quantum story

188

It was somewhat confusing. These very different approaches to relativis-

tic QED all produced similar answers, but nobody understood why.

Enter Dyson.

Dyson’s undergraduate studies at Cambridge, England, were inter-

rupted by the war. He had already developed a reputation as a brilliant

mathematician. In 1943, after just two years of undergraduate study, he

joined the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command to work as a civilian sci-

entist on the operational effectiveness of bombing raids, providing scien-

tifi c advice to the commander in chief. He continued to work on problems

in mathematics and physics in his spare time. After the war, he obtained

a position in the mathematics department at Imperial College, London. It

was his reading of the offi cial report of the Manhattan Project, written by

physicist Henry D. Smyth, that persuaded him to turn to physics.

He returned to Cambridge in 1946, this time focusing on physics.

One of his friends, physicist Harish-Chandra, remarked that theoretical

physics was in such a mess he had decided to switch to pure mathemat-

ics. Dyson replied: ‘That’s curious, I have decided to switch to theoretical

physics for precisely the same reason!’

It had by now become apparent that America was the place to con-

tinue his postgraduate physics studies, and he was recommended to go

to Cornell University in Ithaca to work with Bethe. With support from a

Commonwealth Fellowship, he arrived at Cornell in September 1947.

Bethe had carried out his calculation of the Lamb shift using non-

relativistic QED just a few months previously, and he now assigned his

new English postgraduate student the task of carrying out the calcula-

tion using a fully relativistic QED but for a particle with zero spin. This

was a simpler relativistic calculation than that for a spin-½ particle, like

the electron, and had the advantage that the result was not likely to be

greatly affected by the spin.

Dyson got to know Feynman at Cornell at this time and they became

friends. He recognized Feynman as a profoundly original scientist and

was struck by the contrast with Bethe:

Hans [Bethe] was using the old cookbook quantum mechanics that Dick

[Feynman] couldn’t understand. Dick was using his own private quantum

mechanics that nobody else could understand. They were getting the same

pictorial semi-vision thing

189

answers whenever they calculated the same problems. And Dick could

calculate a whole lot of things that Hans couldn’t. It was obvious to me

that Dick’s theory must be fundamentally right. I decided that my main

job, after I fi nished the calculation for Hans, must be to understand Dick

and explain his ideas in a language that the rest of the world could under-

stand.

As Dyson got to grips with Tomonaga’s and Schwinger’s theories, his

mission expanded beyond providing a comprehensible translation of

Feynman’s approach. He realized that, if any further progress was to be

made, the relationship between the Tomonaga–Schwinger and Feynman

versions of QED had to be made explicit.

Bethe organized for Dyson to spend the second year of his Fellowship

working with Oppenheimer at the Institute for Advanced Study in Prin-

ceton. When the summer term ended at Cornell in June 1948, Dyson had

some time on his hands before he was due to attend a summer school at

the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He therefore agreed to accom-

pany Feynman on a road trip across the country to Albuquerque. This

was hardly a direct route from Ithaca to Ann Arbor, but Dyson welcomed

the opportunity to have Feynman to himself for four days.

On the journey, Feynman opened up to him about his life and his

fears for the near future. Like all physicists who had witnessed an atomic

explosion, he could all too easily imagine the consequences of a nuclear

war. He also talked about his dead wife, Arline: ‘He talked of death with

an easy familiarity which can come only to one who had lived with spirit

unbroken through the worst that death can do,’ Dyson later wrote. They

also argued about physics.

They parted in Albuquerque. Dyson boarded a Greyhound bus to

head back across country, travelling mostly by night. At Ann Arbor

he made new friends and attended Schwinger’s lectures, a ‘marvel of

polished elegance.’ He found Schwinger friendly and approachable,

and spent the afternoons going back through every step of the lectures

and every word of their conversations. He fi lled hundreds of pages with

calculations using Schwinger’s methods and by the end of fi ve weeks he

felt he had mastered the approach as well as anyone, with the exception

of Schwinger himself. When the summer school was over he took a bus

to Berkeley in California.