Allman E.S., Rhodes J.A. Mathematical Models in Biology: An Introduction

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

346 Basic Analysis of Numerical Data

What can we conclude from this experiment? Does the nutrient cause

beans to grow more? Does it cause them to be 150% taller? Would

you feel comfortable making predictions about other beans based only

on this experiment’s result? Would you be surprised if another experi-

menter got different results? Why or why not?

A cautious scientist would be hesitant to conclude anything from this

experiment. In part, this is because of background knowledge that plant growth

seems to be highly variable, even under seemingly similar conditions. Also,

humans often make mistakes, and the experimenter may have unwittingly

botched the experiment.

We would probably feel better drawing a conclusion if the experiment were

repeated many times. (Of course, it might be best to design the experiment

so all the repetitions are done at the same time, because that would cut down

on variation in other factors such as temperature, length of day, etc.) Perhaps

the control and experimental groups should have 10 beans each, or 100, or

1,000.

How does an experimenter decide how many repetitions of an exper-

iment should be done? What trade-offs must be made? If the bean

experiment were repeated with pine trees that were to be grown for 20

years, would it be reasonable to use the same number of repetitions as

for beans?

Pretend we redid the experiment, this time using five beans in each group

(five is used only to keep the amount of data small for illustrative purposes).

The heights in centimeters are measured and found to be

Control: 9.3, 14.2, 11.7, 10.2, 9.8

Experimental: 12.1, 16.3, 13.2, 13.5, 14.9

Notice there is variability in the data, in that not all control plants reached

exactly the same height, nor did the experimental ones. In fact, one of the

control plants is actually taller than three of the experimental ones.

Does the original data for one bean seem to fit with this data? If it does,

would you draw the same general conclusions you might have before?

Would there be any subtle differences in your conclusions? Should you

feel more confident about your conclusion and if so how much more

confident?

How would you briefly summarize, in words and not numbers, your

conclusions based on this data?

A.1. The Meaning of a Measurement 347

If another researcher repeated this experiment with only one plant in

each group and found the control plant was 13.6 cm tall and the ex-

perimental one was 13.4 cm tall, would that data be surprising? What

conclusion would that experimenter be likely to draw based solely on

that data? Is your data compelling enough to say the other researcher’s

conclusion is wrong?

Clearly, an important issue in analyzing this data is understanding the

variability within each group. In fact, you have probably already made

some hypotheses as to why the numbers might be so varied within each

group.

Give as many reasons as you can for the variability in the data.

It’s worth distinguishing two main reasons why data might vary. The first,

called experimental error, is due to mistakes made (perhaps unavoidably) on

the part of the experimenter. For instance, the ruler used for measuring height

might be inaccurate, or the location of the top of the plant might have been

misjudged, or the nutrient may not have been applied in exactly the amount

claimed.

The second reason is that, in dealing with a very complicated system such as

a living organism, there are simply more variables than we can possibly control

at once. For instance, the beans may differ genetically, and the conditions of

soil, light, and air that each plant is exposed to are not identical no matter

how hard we try to make them so. One could argue that this is all a form of

experimental error, in that we have not been able to carry out our experiment

carefully enough. That misses the point, though, because if the experiment

could be carried out so that none of this variability were present, then our

results might actually be less meaningful. Knowing how all clones of a specific

bean would respond to certain very specific conditions may well be less

valuable than knowing how a random sampling of beans will behave in a less

tightly controlled setting.

In studying anything complicated (and biological system are all compli-

cated), we should expect variability in measurements. Experimental error

should, of course, be minimized, but variability in the data often will remain.

We should take lots of measurements to be sure we have a good idea of the

nature of this variability, so that the variability within the data does not ob-

scure the effects we are trying to measure. The more data we have, the better

conclusions we should be able to draw.

We have now arrived at the central problem the discipline of statistics

is designed to address. Too little data can be misleading, so that we draw

incorrect conclusions, but too much data becomes incomprehensible to us.

348 Basic Analysis of Numerical Data

How can we boil down the large quantities of information we need to prevent

mistakes into a simpler, yet meaningful nugget of information? Given that

variability is not just due to error but actually an important part of the systems

we are studying, how can we quantify the natural variability of what we

are experimentally investigating? In what follows, we begin to address these

questions.

A.2. Understanding Variable Data – Histograms and Distributions

People often find pictorial tools useful in understanding data – perhaps be-

cause vision is a more basic function of our brain than numerical reasoning.

Thus, our first step in understanding variable data will be based on a graphical

device, the histogram.

Let’s consider just the control group of beans. Suppose we had 20 beans

in this group, and the heights we measured in centimeters were:

9.3, 9.7, 10.1, 10.2, 10.4, 10.6, 10.7, 10.7, 10.9, 11.0,

11.1, 11.1, 11.3, 11.3, 11.6, 11.7, 11.9, 12.3, 12.4, 13.4.

We begin by grouping the data together in intervals of some convenient

size. For instance, here we see there are two data points between 9 and 10,

seven data points between 10 and 11, eight between 11 and 12, two between

12 and 13, and one between 13 and 14. Thus, we draw the histogram on the

left of Figure A.1.

8 9 12 1310 11 14 8 9 12 1310 11 14

= 1 plant

= 1 plant

Figure A.1. Two histograms describing the same data.

A.2. Understanding Variable Data – Histograms and Distributions 349

8 9 10 11 12 13 14

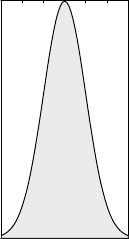

Figure A.2. A normal distribution approximating the histograms in Figure A.1.

Notice that the area of each bar tells us the number of data points in that

interval. Here, the width of each bar is 1, so the height also tells us the number

of data points, but it will be the area that matters.

Grouping the data using a finer scale, with intervals having width 0.5

instead of 1, produces the histogram on the right of Figure A.1. Because area

represents the number of data points, and the bars are now 0.5 wide, a single

plant is denoted by a bar twice as high as what would have appeared in the

left figure.

By insisting on using area to denote the number of data points in an interval,

we have kept the total shaded area in the each of these histograms the same. If

we had used vertical heights to denote the number of data points, the second

graph would look much flatter than the first, since there are fewer points in

each of its intervals. Although the two histograms are very similar, the smaller

interval size in the second one makes it appear a little less step-like.

How would the histogram change if an interval of .25 was used to group

the data? An interval of .05?

Suppose we had 100 data points to work with to construct histograms

in this manner? How would the histograms be different? How would

the histogram change if the grouping interval, or bin size, was made

smaller?

With enough data points, and a sufficiently fine bin size, the histograms

appear to look more and more like the graph in Figure A.2, which we call a

distribution. The jaggedness of the original histogram is smoothed out.

This particular distribution has a bell-shaped curve and is called a normal

distribution. “Normal” here is a technical term that you should not think of as

350 Basic Analysis of Numerical Data

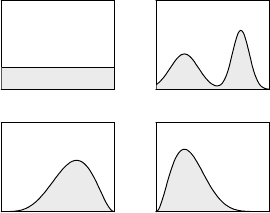

Figure A.3. Four distributions.

having anything to do with meanings like “natural,” “common,” “good,” or

“expected.” Although it is common for data to follow a normal distribution,

it is also common that it does not.

A good way of thinking of the distribution is that if you repeated your ex-

periment endlessly, taking measurements that were fully accurate, and plotted

histograms with finer and finer groupings, then the histograms would look

more and more like the graph of the distribution. Of course, this means the

distribution is not something you can really ever determine exactly. It is a

mathematical idealization of how we believe the data would appear if we had

more data than we do.

Thus, when someone makes a claim that certain data fits a certain distribu-

tion, what they mean is that the data appears to fit such a distribution. In other

words, they are saying that a certain distribution is a good statistical model of

their data.

A few other examples of distributions that might appear to describe data

are shown in Figure A.3.

The distribution in the upper left is said to be uniform, because it describes

data that is equally spread over the interval. The upper right distribution, which

describes data that tends to fall in one lower interval and one higher one, is

said to be bimodal. Notice the bottom two distributions look vaguely like the

normal distribution, but are skewed one way or another. There are, of course,

many other distributions. Those that have been found to be particularly useful

for describing data have been named and studied extensively by statisticians.

Consider the following hypothetical data sets and draw reasonable dis-

tribution curves for them. How would you describe the shape of each

distribution in words?

a: The age at death of a large number of a certain bird are recorded;

mortality is particularly low for young adults.

A.2. Understanding Variable Data – Histograms and Distributions 351

b: The number of puppies in a litter is recorded for a large number of

dogs.

c: Downed trees in a certain forest are located, and the angles the trunks

make with due north are measured.

d: The ages of all individuals on a university campus during the workday

are recorded.

Probably you drew (a) as bimodal, with peaks showing the deaths of the

very young and very old. For (c), if there is no prevailing wind, a uniform

distribution is reasonable; otherwise you might have a distribution that looks

more normal, with a peak at the angle the wind typically blows. Because

university campuses tend to be populated mainly by individuals in their late

teens and 20’s, for (d) you should imagine a skewed distribution, with a peak

to the left and a “tail” stretching off to the right describing faculty and staff

ages.

Notice that (b) is a little different from the others in that any measurement

of the number of puppies in a litter will give an integer value such as 3 or 7,

but never a number like 4.7. When only certain values, separated by gaps, are

possible for data, we say the data is discrete. When data values do not have

to be separated in this way, as in (a) and (c), we say the data is continuous.

For discrete data, it is not too useful to group data in intervals that are

very small, so it is really best to think of something shaped like a histogram,

with step-like features, as giving the distribution. Thus, the distribution for

(b) might be a stepped version of a normal distribution, with peak located at

the average litter size.

Would the data in (d) be discrete or continuous?

Now that the concept of a distribution is clear, let’s turn things around.

Suppose before doing an experiment, we hypothesize that the data we will

obtain will fit the normal distribution of Figure A.4.

Before continuing, decide if each of the following data sets seems con-

sistent with that hypothesis and state how confident you feel about each

answer.

a: 2.0, 3.6, 3.8, 4.1, 4.3, 6.9

b: 6.9

c: 3.8, 3.9, 3.9, 4, 4, 4.1

d: 1.1, 1.4, 2.1, 6.3, 6.5, 7.1

You should feel the given distribution fits (a) well. For (b), with only a

single number, we do not have much to go on. The distribution shows it is

352 Basic Analysis of Numerical Data

1234567

Figure A.4. A normal distribution.

possible to get numbers around 6.9, but they are not as likely as those around

4. The data in (c) seems like it would be better described by a distribution with

a much narrower and higher peak around 4. For (d), a bimodal distribution

seems more reasonable. Still, with so few data points, any of these might in

fact come from an experiment described by the distribution in the figure.

Can you make up a set of a few data points that you can say with

complete certainty do not arise from the normal distribution of Figure

A.4?

Because the graph in Figure A.4 lies above the horizontal axis for all

values, there is some likelihood of the experiment producing any number you

might mention. While a large number of data points whose histogram is not

similar to the figure makes it very likely the distribution does not describe the

experiment, you cannot completely rule out the possibility.

A.3. Mean, Median, and Mode

When approaching a new set of data, drawing a histogram to understand the

nature of the distribution is the best place to begin. Then, there are several

numerical ways of describing the key features of the distribution.

The first question to be addressed is how do we locate the central tendency

of the data. Does the data tend to cluster around some single value? If it does

appear to cluster, how do we determine that value?

A quick glance at the bimodal distribution shows that there is not always

a single central tendency to locate. If we are faced with a bimodal distribu-

tion, then often we should expect that we are really dealing with a data set

that should be broken down into two smaller sets that should be analyzed

A.3. Mean, Median, and Mode 353

separately. Perhaps we have missed some important experimental variable

and need to rethink our investigation.

Can you think of some data that might be bimodally distributed? Can

it be naturally broken into two smaller data sets?

For simplicity, assume we have a data set producing a histogram with a

single major hump, perhaps not too pronounced and maybe not symmetrical,

but that is at least visually the dominant feature.

There are three distinct ways of choosing what might be called the central

tendency of the data, each with its own strength and weaknesses.

The Mode: The mode is simply the data value that occurs most frequently.

That definition must be modified a bit in practice, though, since if you look

back at the list of 20 bean heights at the beginning of Section 2, you will see

that three of them occurred twice and all the others once. It is perhaps better

to do some grouping and say that with an interval of 1 the mode for that data

was between 11 and 12, and with a grouping interval of 0.5, it was between

11 and 11.5.

How can you tell by glancing at a histogram what the mode of the data

is?

Can the mode change if you use a different grouping interval?

Can a change in a few data values change the mode by much? Is the

effect different if the largest or smallest data points are changed, or

those midsized?

The Median: This is the data value that occurs in the precise middle of all

the data values when they are arranged in order. For instance, in the data of

20 bean heights in Section 2, since we have an even number of data points,

we find 11.0 and 11.1 are the middle values. The best we can do is average

the two and report 11.05 as the median.

How can you tell by a glance at a histogram where the median is located?

Because in a histogram area is used to denote the number of data points,

the median will be the value where a vertical line splits the total area in half.

Since distributions are idealizations of histograms, this also allows the median

to be located on the graph of a distribution.

Could the median change much if a few of the data points were changed?

How sensitive is the median to changes in extreme data points vs. those

near the middle?

354 Basic Analysis of Numerical Data

The median is insensitive to changes of the more extreme data points,

unless of course these values, are changed so much that they jump from one

side of the median to the other. The median may move if data points closest

to the median are changed.

The Mean: The mean of a set of data is just the usual average. To calculate

it, you add up all the data values and then divide this sum by the number of

values you have added. If we have n data values denoted by x

1

, x

2

, x

3

,...,x

n

,

then the mean µ is simply

µ =

1

n

(

x

1

+ x

2

+ x

3

+···+x

n

)

=

1

n

n

i=1

x

i

What is the mean of the 20 bean heights in Section 2?

To guess the mean of a data set by looking at a histogram is harder than

estimating the mode or median. Although we will not explain why here,

because that would involve a detour into physics, the mean is located at the

center of mass of the histogram along the horizontal axis. This is the point

along the horizontal axis at which the histogram would balance if you imagine

it as cut out of a piece of cardboard. This interpretation will help you in getting

a rough idea of the location of a mean from a histogram, but do not expect to

be able to pin down a mean very accurately without doing a calculation.

Does the mean you calculated for the bean data appear to be at this

balance point on the histogram of the data?

How sensitive is the mean to changes in only a few of the data points?

Does it matter whether these points are near the extremes or in the

middle?

Changing an extreme value can have a large effect on a mean. If you think

in terms of a balance point for a histogram, moving an extreme value outward

is likely to cause the histogram to tip in that direction, just as a see-saw does if

a weight far out on an arm is moved farther out. That means the new balance

point must be found by moving in the same direction. On the other hand,

changing a data value near the mean has little effect on the mean – just as on

a see-saw weights near the pivot have little effect.

Can you change just one value in the bean height data set so that while

the mode and median do not change, the mean does?

Notice for a normal distribution the mode, median, and mean would all be

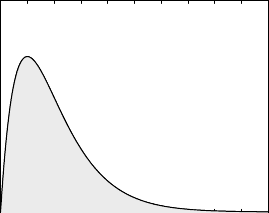

the same. In general, though, the three are not the same. Figure A.5 provides a

A.4. The Spread of Data 355

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Figure A.5. Mean = 4, median ≈ 3.3, and mode = 2.

good illustration of a skewed distribution. The median, which splits the area,

is around 3.3 on the horizontal axis. The mean, which is the balance point, is

further to the right, at 4, due to the rightward stretching tail. The mode, which

is at the peak, is around 2.

Look back over all the histograms and distributions in this appendix

and estimate where the mode, median, and mean are on each.

In practice, all three of these concepts are used to describe data. The mean

is probably used most frequently, the median next most, and the mode the

least, but this varies depending on what is being studied.

For instance, in reporting incomes and housing prices, governments tends

to emphasize the median as being the most important of the three. This is

simply because the median is less sensitive to extreme values. Relatively few

very large values can cause the mean to be much larger than the median.

Would you be more interested in knowing the mean, median, or mode

of life spans for your society? Which do you think is most optimistic?

A.4. The Spread of Data

The concepts of mean, median, and mode are useful in that they allow us to

represent the most important feature of a data set with a single number. The

drawback of reporting only them is that we draw attention away from the

fact that the data has variation in it. It is useful to have an easily reportable

measure of the spread of the data as well.

When the median is chosen to represent the central tendency of the data,

the most natural way of specifying the spread of the data is through reporting

quartiles. Just as the median is the value that divides all the data points in