A History of Modern Iran by Ervand Abrahamian

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

To receive land, peasants had to join rural cooperatives administered by the

ministries of agriculture and rural affairs. In some areas the government set

up health clinics and literacy classes. A European anthropologist visiting the

Boir Ahmadis noted: “One is amazed at the high level of centralization

achieved within the last decade. The government now interferes in practi-

cally all aspects of daily life. Land is contracted for cash by the government;

fruits get sprayed, crops fertilized, animals fed, beehives set up, carpets

woven, goods and babies born, populations controlled, women organized,

religion taught and diseases controlled – all by the intervention of the

government.”

21

What is more, as the nomadic population shrank further,

small tribal groups that had given Iran the appearance of being a social

mosaic disappeared into oblivion. Similarly, terms such as tireh and taifeh,

as well as ilkhan and ilbeg, became obsolete. They merely conjured up vague

images of a bygone esoteric age.

While land reform transformed the countryside, five-year plans drawn up

by the Plan and Budget Organization brought about a minor industrial

revolution. They improved port facilities; expanded the Trans-Iranian

Railway, linking Tehran to Mashed, Tabriz, and Isfahan; and asphalted the

main roads between Tehran and the provincial capitals. They financed

petrochemical plants; oil refineries; hydroelectric dams – named after mem-

bers of the royal family; steel mills in Ahwaz and Isfahan – the Soviets

constructed the latter; and a gas pipeline to the Soviet Union. The state

also bolstered the private sector both by erecting tariff walls to protect

consumer industries and by channeling low-interest loans via the Industrial

and Mining Development Bank to court-favored businessmen. Old landed

families – such as the Bayats, Moqadams, Davalus, Afshars, Qarahgozlus,

Esfandiyaris, and Farmanfarmas – became capitalist entrepreneurs. Le Monde

wrote that the shah – much like the kings of early nineteenth-century France –

encouraged entrepreneurs to “enrich themselves,” showering them with

low-interest loans, exempting them from taxation, and protecting them

from foreign competition.

22

Between 1953 and 1975, the number of small

factories increased from 1,500 to more than 7,000; medium-sized factories

from 300 to more than 800; and large factories – employing more than 500

workers – from fewer than 100 to more than 150. They included textile,

machine tool, and car assembly plants in Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz, Tabriz,

Ahwaz, Arak, and Kermanshah. The smaller plants specialized in clothing,

food processing, including beverages, cement, bricks, tiles, paper, and home

appliances. The regime’s showpieces were the Dezful Dam in Khuzestan,

the steel mills in Isfahan, and the nuclear plant in Bushire. Key production

figures indicate the extent of this industrial revolution.

Muhammad Reza Shah’s White Revolution 133

The state also pressed ahead with social programs. The number of

educational institutions grew threefold after the launching of the White

Revolution. Enrollment in kindergartens increased from 13,300 to 221,990;

in elementary schools from 1,640,000 to 4,080,00; in secondary schools

from 370,000 to 741,000; in vocational schools from 14,240 to 227,000;in

colleges from 24,885 to 145,210; and in colleges abroad from 18,000 to

80,000. What is more, a Literacy Corps – modeled on the Cuban version –

was declared to be an integral part of the White Revolution. It helped raise

the literacy rate from 26 to 42 percent. Health programs increased the

number of doctors from 4,000 to 12,750; nurses from 1,969 to 4,105;

medical clinics from 700 to 2,800; and hospital beds from 24,100 to

48,000. These improvements, together with the elimination of famines

and childhood epidemics, raised the overall population from 18,954

,706

in 1956 – when the first national census was taken – to 33,491,000 in 1976.

On the eve of the revolution, nearly half the population was younger than

sixteen. The White Revolution also expanded to include women’s issues.

Women gained the right to vote; to run for elected office; and to serve in the

judiciary – first as lawyers, later as judges. The 1967 Family Protection Law

restricted men ’s power to get divorces, take multiple wives, and obtain child

custody. It also raised the marriageable age for women to fifteen. Although

the veil was never banned outright, its use in public institutions was

discouraged. What is more, the Literacy and Health Corps established

special branches designed to extend educational and medical facilities,

especially birth control information, to women.

These changes produced a complex class structure.

23

At the apex was an

upper class formed of a narrow circle of families linked to the Pahlavi court –

the royal family itself, senior politicians and government officials, military

Table 11 Industrial production, 1953–77

1953 1977

Coal (tons) 200,000 900,000

Iron ore (tons) 5,000 930,000

Steel and aluminum (tons) – 275,000

Cement (tons) 53,000 4,300,000

Sugar (tons) 70,000 527,000

Electricity (kw hours) 200 million 14 billion

Cotton textiles (meters) 110 million 533 million

Tractors – 7,700

Motor vehicles – 109,000

134 A History of Modern Iran

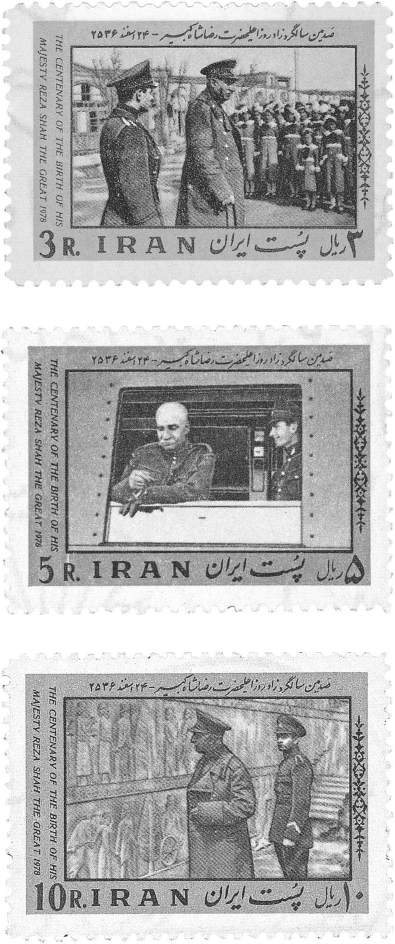

5.1 Set celebrating aspects of the White Revolution

5 Stamps (1963–78)

5.2 Set commemorating Reza Shah

136 A History of Modern Iran

5.2 (cont.)

5.3 Stamp set commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Pahlavi dynasty

officers, as well as court-connected entrepreneurs, industrialists, and com-

mercial farmers. Some came from old families; others were self-made men

with court connections; yet others had married into the elite. Together they

owned more than 85 percent of the large firms involved in insurance,

banking, manufacturing, and urban construction. Although the vast major-

ity came from Shi’i backgrounds, a few had Bahai connections, and some

had joined the secretive Freemasons. This provided fuel for those who

claimed that Iran was really controlled behind the scenes by the British

through the Freemasons and by the Zionists through the Bahais who had

located their headquarters in Haifa.

The middle layers were formed of two very distinct classes: the bazaar petty

bourgeoisie which constituted a traditional middle class; and a modern

middle class composed of white-collar employees and college-educated pro-

fessionals. The propertied middle class constituted more than a million

families – as much as 13 percent of the working population. It included not

only bazaar shopkeepers and workshop owners, but also small manufacturers

and absentee farmers owning between 50 and 100 hectares. It also included

much of the ulama – both because of family links and because of historic links

between mosque and bazaar. Despite economic modernization, the bazaar

continued to control as much as half of the country’s handicraft production,

two-thirds of its retail trade, and three-quarters of its wholesale trade. It

continued to retain craft and trade guilds as well as thousands of mosques,

hayats (religious gatherings), husseiniehs (religious lecture halls), and dastehs

(groups that organized Muharram processions). Ironically, the oil boom gave

the traditional middle class the opportunity to finance religious centers and

establish private schools that emphasized the importance of Islam. They were

specifically designed to prepare the children of the bazaaris for the top

universities. Thus the oil money helped nourish tradition.

The salaried middle class numbered more than 700,000 – some 9 percent of

the working population. It included 304,000 civil servants in the ever-expand-

ing ministries; some 200,000 teachers and school administrators; and in excess

of 60,000 managers, engineers, and professionals. The total exceeded one

million, including college students and other aspiring members of the class. In

the past, the term intelligentsia – rowshanfekr – had been synonymous with

the salaried middle class. But with the rapid expansion of the salaried class,

the term had become more differentiated and specifically associated with

intellectuals – writers, journalists, artists, and professors. The intelligentsia

continued to be the bearers of nationalism and socialism.

The urban working class numbered as many as 1,300,000 – more than 30

percent of the labor force. It included some 880,000 in modern industrial

138 A History of Modern Iran

factories; 30,000 plus oil workers; 20,000 gas, electrical, and power plant

workers; 30,000 fishery and lumberyard workers; 50,000 miners; 150,000

dock workers, railwaymen, truck drivers, and other transport workers; and

600,000 workers in small plants. The total grows even larger if one adds the

rapidly increasing army of shantytown poor formed of immigrants squeezed

out of their villages by the lack of land. Migrants scraped out a living as

construction workers, and, if there were no jobs on construction sites, as

peddlers and hawkers. Tehran took in the largest influx of rural migrants,

with population growth from 1.5 million in 1953 to more than 5.5 million in

1979. By the time of the revolution, 46 percent of the country’s population

lived in urban centers.

The rural population – some 40 percent of the labor force – consisted of

three strata: prosperous farmers, hard-pressed smallholders, and village

laborers. The first layer included former village headmen, bailiffs, and

oxen-owning tenant sharecroppers who had benefited most from land

reform. They numbered around 600,000 – less than 17 percent of the

rural population. The second included some 1,100,000 sharecroppers who

had received less than 10 hectares – the minimum needed in most regions.

Many had no choice but to exchange their small plots for shares in state

cooperatives. The third comprised peasants without sharecropping

rights. Having received no land whatsoever, they survived as farm

hands, shepherds, laborers, day commuters to nearby towns, and wage

earners employed in the many small plants that flourished in the country-

side during the early 1970s – small plants manufacturing carpets,

shoes, clothes, and paper. Some migrated to the urban centers. Thus

the White Revolution failed to provide land to the bulk of the rural

population.

social tensions

These changes intensified social tensions in three major ways. First, they

more than quadrupled the combined size of the two classes that had posed

the most serious challenge to the Pahlavis in the past – the intelligentsia and

the urban working class. Their resentments also intensified since they were

systematically stripped of organizations that had in one way or another

represented them during the interregnum – professional associations, trade

unions, independent newspapers, and political parties. At the same time,

land reform had undercut the rural notables who for centuries had con-

trolled their peasants and tribesmen. Land reform had instead produced

large numbers of independent farmers and landless laborers who could

Muhammad Reza Shah’s White Revolution 139

easily become loose political cannons. The White Revolution had been

designed to preempt a Red Revolution. Instead, it paved the way for an

Islamic Revolution. Furthermore, the steady growth in population, com-

pounded by the shortage of arable land, produced ever-expanding shanty-

towns. By the mid-1970s, the regime faced a host of social problems of a

magnitude unimaginable in the past.

Second, the regime’s preferred method of development – the “trickle-

down” theory of economics – inevitably widened the gap between haves and

have-nots. Its strategy was to funnel oil wealth to the court-connected elite

who would then set up factories, companies, and agrobusinesses. In theory,

wealth would trickle down. But in practice, in Iran, as has been the case in

many other countries, wealth tended to stick at the top, with less and less

finding its way down the social ladder. Wealth, like ice in hot weather,

melted in the process of being passed from hand to hand. The result was not

surprising. In the 1950s, Iran had one of the most unequal income

Upper class

Pahlavi family; military officers; senior civil servants,

court-connected entrepreneurs

0.1%

Middle classes

10%

32%

modern (salaried)

professionals

civil servants

office employees

college students

13% traditional

(propertied)

clerics

bazaaris

small-factory owners

workshop owners

commercial farmers

Lower classes

urban

industrial workers

small factory workers

workshop workers

construction workers

peddlers

unemployed

45% rural

landed peasants

near landless peasants

landless peasants

rural unemployed

Figure 1 Class structure (labor force in the 1970s)

140 A History of Modern Iran

distributions in the Third World. By the 1970s, it had – according to the

International Labor Office – one of the very worst in the whole world.

24

Although we have no hard data on actual income distribution, the Central

Bank carried out surveys on household urban expenditures in 1959–60 and

1973–74 – a methodology that would inevitably underestimate real inequal-

ity. The 1959–60 survey showed that the richest 10 percent accounted for

35.2 percent of total expenditures; the poorest 10 percent only 1.7 percent of

expenditures. The figures were worse in 1973–74. They showed that the

richest 10 percent accounted for 37.9 percent; and the poorest 10 percent 1.3

percent of total expenditures. A leaked document from the Plan and Budget

Organization showed that the income share of the richest 20 percent of the

urban population had grown from 57 to 63 percent in the period between

1973 and 1975.

25

It also showed that the gap between urban and rural

consumption had dramatically widened. Inequality was most visible in

Tehran where the rich lived in their northern palaces and the poor in

their shantytown hovels without public amenities – especially a decent

transport system. A member of the royal family was rumored to have

commented that “if people did not like being stuck in traffic jams why

didn’t they buy helicopters?” In the words of a Pentagon journal, the oil

boom had brought “inequality” and “corruption to a boiling point.”

26

Finally, the White Revolution and the subsequent oil boom produced

widespread resentments by drastically raising but not meeting public

expectations. It was true that social programs made strides in improving

educational and health facilities. But it was equally true that after two

decades, Iran still had one of the worst infant mortality and doctor–patient

Table 12 Urban household expenditures (decile

distribution in percent)

Deciles (poorest to richest) 1959–60 1973–74

1st 1.71.3

2nd 2.92.4

3rd 4.03.4

4th 5.04.7

5th 6.15.0

6th 7.36.8

7th 8.99.3

8th 11.811.1

9th 16.417.5

10th 35.337.9

Muhammad Reza Shah’s White Revolution 141

rates in the Middle East. It also had one of the lowest percentages of the

population in higher education. Moreover, 68 percent of adults remained

illiterate, 60 percent of children did not complete primary school, and only

30 percent of applicants found university places within the country.

Increasing numbers went abroad where they remained for good. By the

1970s, there were more Iranian doctors in New York than in any city outside

Tehran. The term “brain drain” was first attached to Iran.

It was true that the White Revolution provided some farmers with land,

cooperatives, tractors, and fertilizers. But it was equally true that the White

Revolution did not touch much of the countryside. Most peasants received

no or little land. Most villages were left without electricity, schools, piped

water, rural roads, and other basic amenities. What is more, government-

imposed prices on agricultural goods favored the urban sector at the expense

of the countryside. This lowered incentives – even for those farmers who

had benefited from land reform. This, in turn, stifled production at a time

of rapid population growth. As a result, Iran, which in the 1960s had been a

net exporter of food, was spending as much as $1 billion a year in the mid-

1970s importing agricultural products. It is true that economic growth did

benefit those who gained access to modern housing and such consumer

goods as refrigerators, telephones, televisions, and private cars. But it is

equally true that this growth tended to widen the gap not only between rich

and poor, but also between the capital city and the outlying provinces. Of

course, the state’s center of gravity was very much located at the capital. The

Industrial and Mining Bank compounded this imbalance by channeling

60 percent of its loans into the capital. By the mid-1970s, Tehran – with less

than 20 percent of the country’s population – had more than 68 percent of

its civil servants; 82 percent of its registered companies; 50 percent of its

manufacturing production; 66 percent of its university students; 50 percent

of its doctors; 42 percent of its hospital beds; 40 percent of its cinema-going

public; 70 percent of its travelers abroad; 72 percent of its printing presses;

and 80 percent of its newspaper readers. One in ten of Tehran’s residents

had a car; elsewhere the figure was one in ninety.

27

In the words of a British

economist: “Those who live in Tehran have the chance of better access to

education, health facilities, the media, jobs and money – to say nothing of

access to the decision-making processes. Not surprisingly people in villages

or other towns are prepared to come to Tehran in the hope of better life,

ignoring the problems of high rents, overcrowding and pollution.”

28

Frances

FitzGerald summed up the overall disparities: “Iran is basically worse off

than a country like Syria that has had neither oil nor political stability. The

reason for all this is simply that the Shah has never made a serious attempt at

142 A History of Modern Iran