Zdunkowski W., Trautmann T., Bott A. Radiation in the atmosphere: A course in Theoretical Meteorology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

9.6 Material characteristics and derived directional quantities 365

Jahnke and Emde (1945), we may extract the expression

P

m

n

(x) =

(n + m)!

2

m

m!(n − m)!

(1 − x

2

)

m/2

1 −

(n − m)(n + m + 1)

m + 1

1 − x

2

+···

(9.156)

for the associated Legendre polynomials. For the scattering angle = 0 so that

x = 1 we find for m =1 the following simple expressions for the π

n

and τ

n

functions

π

n

(x)

x=1

=

n(n + 1)

2

, τ

n

(x)

x=1

=

n(n + 1)

2

(9.157)

Thus for the function S(0) appearing in (9.144) we obtain

S(0) = S

1

(0) = S

2

(0) =

∞

n=1

2n + 1

2

a

s

n

+ b

s

n

(9.158)

yielding for C

ext

C

ext

=−

2π

k

2

0

∞

n=1

(2n + 1)

a

s

n

+ b

s

n

(9.159)

We will now briefly discuss Rayleigh scattering which we have treated as a

special case of Mie scattering. Without going into details, there is a problem if we

try to evaluate the Rayleigh extinction coefficient for a real index of refraction by

using equation (9.144). In this case we obtain C

ext

= 0 which cannot be correct.

Van de Hulst (1957) and Goody (1964a) trace this problem back to the Rayleigh

theory where radiation reaction on the oscillating dipole is neglected. Because of

this the phase of the scattered wave is incorrect. Due to our simplified treatment of

a

s

n

and b

s

n

we have introduced the same type of problem.

We overcome this problem by recalling that in the absence of absorption the

extinction cross-section is equal to the scattering cross-section. Thus we find the

scattering cross-section by substituting (9.118) and (9.119) into (9.155). A brief

derivation shows that the scattering cross-section for a dielectric sphere of radius

a can then be expressed by

C

sca

=

8π

3k

2

0

(N

2

− 1)

2

(N

2

+ 2)

2

ρ

6

0

(9.160)

This equation was derived for incident linearly polarized light, but it is also valid

for incident natural light. The reason for this is that unpolarized light can be treated

as two beams of incoherent light of equal intensity. We have used this fact already

when deriving equation (9.155).

366 Light scattering theory for spheres

We will close this section with a few remarks stating that the Rayleigh theory can

be improved. Since molecules are not perfect dielectric spheres a correction term

must be included in equation (9.160) which is known as a depolarization correction.

Practically all tabulations of the scattering coefficient include this factor showing

that this increases the extinction coefficient by about 7%. A condensed derivation

of the correction factor is given by Goody (1964a). Finally, we would like to remark

that the inverse power law for the scattering coefficient is not exactly a fourth power

law since the index of refraction is wavelength dependent and slightly decreasing

with increasing wavelength. If this fact is incorporated into the theory then within

the visible spectrum the scattering coefficient is proportional to λ

−4.08

.

9.6.2 The scattering function and the scattering phase function

At this point we wish to discuss the scattering of unpolarized light by a spherical

particle contained in a small volume element V . In analogy to the scattering

function S(µ, ϕ, µ

,ϕ

) introduced in terms of the principles of invariance (see

Chapter 3), we now wish to define the scattering function

˜

P(cos ) in the form

needed to evaluate the RTE. This type of scattering function is defined as the ratio

of the scattered radiant flux dφ

s

per solid angle element d and volume element

V to the incoming radiant flux density dE

i

, that is

˜

P(cos ) =

dφ

s

(cos )

Vd

s

dE

i

=

r

2

dE

s

(cos )

VdE

i

(9.161)

The second expression follows from d = dA/r

2

and dE

s

= dφ

s

/dA. The units

of

˜

P(cos ) are (m

−1

sr

−1

). Utilizing (9.149) we obtain immediately

˜

P(cos ) =

i

1

(cos ) +i

2

(cos )

2k

2

0

V

(9.162)

The scattering function agrees with the differential scattering coefficient introduced

in Section 1.6.2, see (1.42). Thus the ordinary scattering coefficient, defined in

(1.44), may also be written as

k

sca

=

0

4π

˜

P(cos )d (9.163)

Analogously to (1.45) we obtain the scattering phase function P(cos )as

P(cos ) =

4π

k

sca

˜

P(cos )

(9.164)

Hence we directly see that P(cos ) is normalized, that is

0

4π

P(cos )d = 4π (9.165)

9.7 Selected results from Mie theory 367

1000 10 1 0.1 0.1 1 10 1000

0.1

0.01

0.1

1

= 180°

Incident radiation

Θ

Θ

= 90°

Θ

Θ

= 270°

Θ = 0°

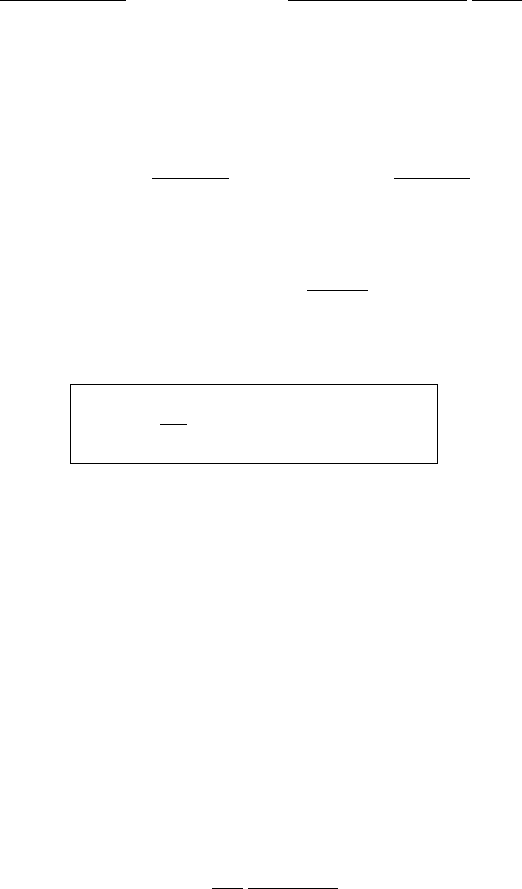

Fig. 9.7 Polar plot of P(cos ) for N =1.33 + 0i and three different size param-

eters. Dashed curve: x = 0.01, lower solid curve: x =1, upper solid curve: x =50.

Finally, it is a simple task to show that for Rayleigh scattering the phase function

reduces to

P

Rayleigh

(cos ) =

3

4

(1 + cos

2

)

(9.166)

The proof of this equation will be left to the exercises. Application of (9.166) to

(6.25) shows that in case of Rayleigh scattering the backscattering coefficient is

given by 0.5.

9.7 Selected results from Mie theory

In this section we will present various results which follow from the Mie theory.

Figure 9.7 depicts a polar plot of the Mie scattering phase function P(cos ) for a

nonabsorbing sphere with refractive index N =1.33 + 0i. The figure shows three

curves for the size parameter x =2πr/λ selected as 0.01, 1 and 50. The value of

P(cos ) is given by the radial distance between a point on the curve and the origin

of the polar plot. The Mie phase function has rotational symmetry with respect to

the axis of incidence. Thus, for better comparison all three curves have been drawn

in a single plot, i.e. for each size parameter the full phase function is obtained by

reflecting the corresponding curve on the axis of incidence.

As can be seen from the figure, for very small size parameters of x =0.01

(dashed curve) the phase function is symmetric with respect to the ordinate denot-

ing the scattering directions =90

◦

and =270

◦

. For such a small size parameter,

P(cos ) approaches the Rayleigh phase function (9.166). For x =1 this symmetry

368 Light scattering theory for spheres

1 10 100

x = 2pr/l

0

1

2

3

4

Q

sca

= 0.1

= 0.01

= 1

k = 0

k

k

k

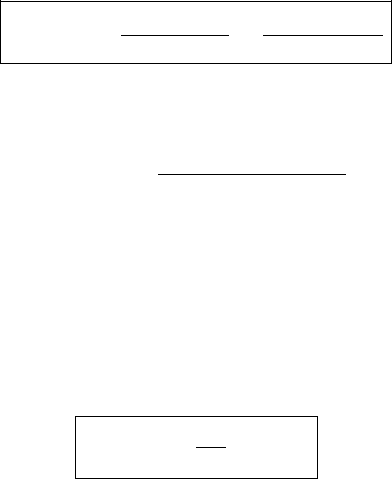

Fig. 9.8 Efficiency factor for scattering for different values of κ.

of the phase function with respect to the ordinate is approximate only with a small

enhancement in the forward direction. Nevertheless the curve is still rather smooth.

For x =50 the phase function is very asymmetric with respect to the ordinate

showing a very strong peak in the forward direction. Note the logarithmic scale of

the axes of the polar plot. Moreover, the curve is characterized by numerous ripples

indicating the complex scattering behavior of particles with large size parameters.

For visible wavelengths x =1 is representative for a small particle having a radius of

approximately 0.1

µm, while x = 50 is typical for a cloud droplet with radius 5 µm.

In order to calculate the wavelength-dependent efficiency factors Q

abs

, Q

sca

and

Q

ext

as defined in (9.132), we must specify the radius r of the scattering particle

and the wavelength λ. These two physically significant quantities enter the Mie

scattering coefficients a

s

n

and b

s

n

in terms of the size parameters ρ

0

and ρ, see (9.90)

and (9.92). For the evaluation of (9.92), the wavelength-dependent complex index

of refraction N , defined in (8.253), is also needed. This quantity can be extracted

from suitable tables. As soon as the coefficients a

s

n

, b

s

n

are available, the scattering

and extinction cross-sections C

sca

, C

ext

can be calculated from (9.155) and (9.159),

whereas the absorption cross-section follows from (9.131).

As a first example, let us consider Figures 9.8–9.10 which show the distribution

of Q

sca

, Q

abs

and Q

ext

as a function of the size parameter x =ρ

0

=2πr/λ for a fixed

1 10 100

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

Q

abs

x = 2pr/l

k = 1

k = 0.1

k = 0.01

Fig. 9.9 Efficiency factor for absorption for different values of κ.

1 10 100

0

1

2

3

4

Q

ext

x = 2pr/l

k = 0.1

k = 0.01

k = 1

k = 0

Fig. 9.10 Efficiency factor for extinction for different values of κ.

370 Light scattering theory for spheres

real part n =1.33 of the complex index of refraction. This value is representative of

pure water in the visible part of the spectrum. By assuming values of κ =0, 0.01, 0.1

and κ =1.0, we wish to investigate in which way the efficiency factors are modified

by nonzero absorption indices. For these κ-values four curves of Q

sca

are depicted

in Figure 9.8. In the right part of the figure, the distribution Q

sca

not only shows

a wave-like behavior with decreasing amplitudes but also many ripples interfering

with the distribution curve. The major maxima and minima result from interference

of light which is transmitted and diffracted by the spherical particle. The superposed

ripples are not numerical inaccuracies. They are due to edge rays which are grazing

and traveling around the sphere thereby emitting small amounts of energy in all

directions. These ripples, however, are not of major physical concern and impor-

tance to us. As will be seen, even small κ-values, e.g. κ =0.01, will almost remove

this fine structure. For κ =0.1 only one major maximum is observed while for κ =1

the entire wave structure has disappeared.

Figure 9.9 displays the distributions of the absorption efficiency factors Q

abs

for

the values of the absorption index κ used in the previous figure. If no absorption

takes place, i.e. κ = 0, we must have Q

abs

= 0. It is seen that with increasing values

of κ the maxima of the curves are shifted toward lower values of the size parameter.

Ripple patterns are barely visible, only for κ = 0.01 they can be identified for values

of the size parameter of approximately 5–50.

Figure 9.10 depicts the distributions of the extinction efficiency factors Q

ext

.For

κ = 0, of course, the efficiency factor for scattering and extinction are identical. Of

particular interest is the asymptotic behavior of Q

ext

for very large values of x where

Q

ext

approaches the value of 2 for all κ. At first it is surprising that the extinction

cross-section is twice as large as the geometrical cross-section of the spherical

particle. This apparently contradicts the observations, but the effect is real. A part

of the light is scattered in the forward direction and cannot be distinguished from

the incoming light. Since the particle is large, the so-called extinction paradox can

be explained in terms of geometric optics. A very minute part of the incoming light

traverses the sphere in the direction of the scattering angle zero. The remaining

light intercepted by the large particle suffers a change in direction by reflection and

refraction and is, therefore, scattered out of the forward beam. This explains one

half of Q

ext

= 2. The other half is the radiation which is diffracted by the ‘edge’ of

the sphere. According to Babinet’s principle an opaque circular disk forms the same

diffraction pattern as a hole of the same radius in an opaque screen. Fraunhofer

diffraction theory (incident and diffracted wave are essentially plane) shows that

all rays passing through the hole, except for the axial ray, are deviated or scattered.

Most of the edge-diffracted light is contained within the maximum of the diffraction

pattern centered around the forward direction whose angular width is defined by the

9.7 Selected results from Mie theory 371

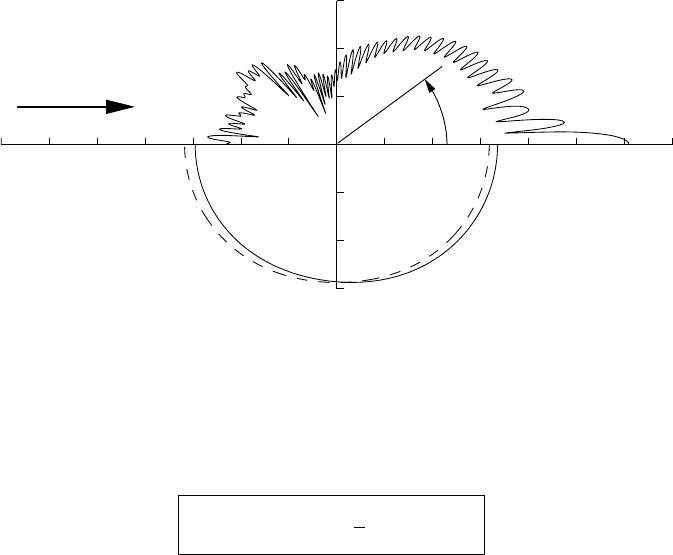

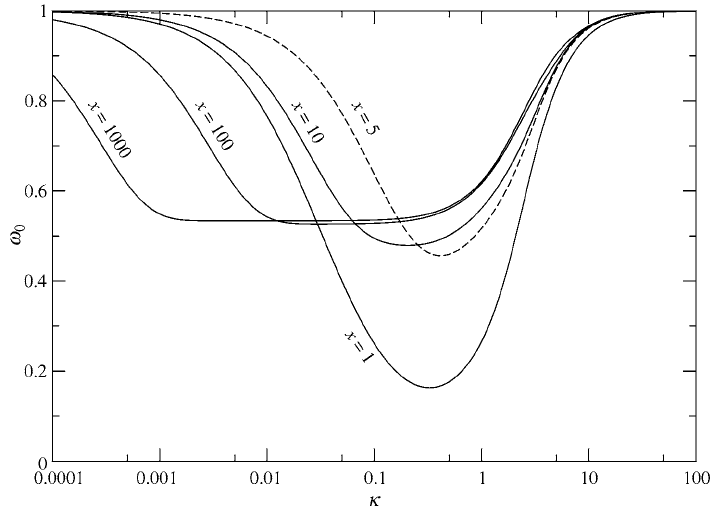

Fig. 9.11 Single scattering albedo as a function of the absorption index for different

values of the size parameter.

first minimum of the diffraction pattern. For a simple yet illuminating discussion of

the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern of a single slit see, for example, Fowles (1967).

Discussions of the extinction paradox can be found in Van de Hulst (1957), Johnson

(1960), Goody (1964a), Houghton (1985) and elsewhere.

As another example for the results of the Mie theory Figure 9.11 shows the single

scattering albedo ω

0

as a function of κ for different values of the size parameter x.It

is not surprising that for a given x with increasing κ, i.e. with increasing absorption,

the single scattering albedo decreases strongly. However, instead of going to zero ω

0

decreases to a minimum value and then rises steadily to ω

0

= 1 which corresponds

to perfect scattering. To explain this effect in simple terms seems difficult, but it is

the result of exact Mie computations. In order to at least qualitatively appreciate this

result, let us consider a plane wave which is incident on the boundary of a medium

having a complex index of refraction as defined by (8.253). For normal incidence

a simple reflection formula exists as is shown, for example, in Fowles (1967). For

metals the absorption index κ is large, resulting in a high value of the reflectance

which approaches unity as κ becomes infinite. This compares with ω

0

= 1 when

perfect scattering takes place.

372 Light scattering theory for spheres

In order to model the attenuation caused by a particle population as observed in a

cloud, we need to introduce a particle distribution function n(r). Such a function may

have various mathematical forms. Here we will model a cloud droplet population

with the help of the rather versatile standard modified gamma distribution, a type

of function already used by Deirmendjian (1969). It is expressed as

n(r) = Cr

(1−3b)/b

exp

−

r

ab

, C = N (ab)

(2b−1)/b

1 − 2b

b

(9.167)

where C is a normalization constant and N (cm

−3

) the total number of cloud

particles per unit volume of air which is related to n(r)by

N =

∞

0

n(r)dr (9.168)

It can be shown that the parameters a and b are equal to the effective particle radius

and the dimensionless effective variance of the size distribution, i.e.

a =

1

G

∞

0

rπr

2

n(r)dr , b =

1

Ga

2

∞

0

(r − a)

2

πr

2

n(r)dr (9.169)

G is the total geometric cross-section of the entire particle population per unit

volume, that is

G =

∞

0

πr

2

n(r)dr (9.170)

In the exercises it will be shown that the integrations of (9.169) indeed result in

the effective radius and the effective variance. As will be seen, the units of the

distribution function n(r) are (cm

−3

cm

−1

) which is number of particles per cm

3

and per radius interval measured in cm. Of course, we could have used the length

unit m, but it is customary to use the smaller unit cm. By adjusting the length

parameter a (cm) and the dimensionless parameter b, equation (9.167) may also be

applied to describe an aerosol particle spectrum.

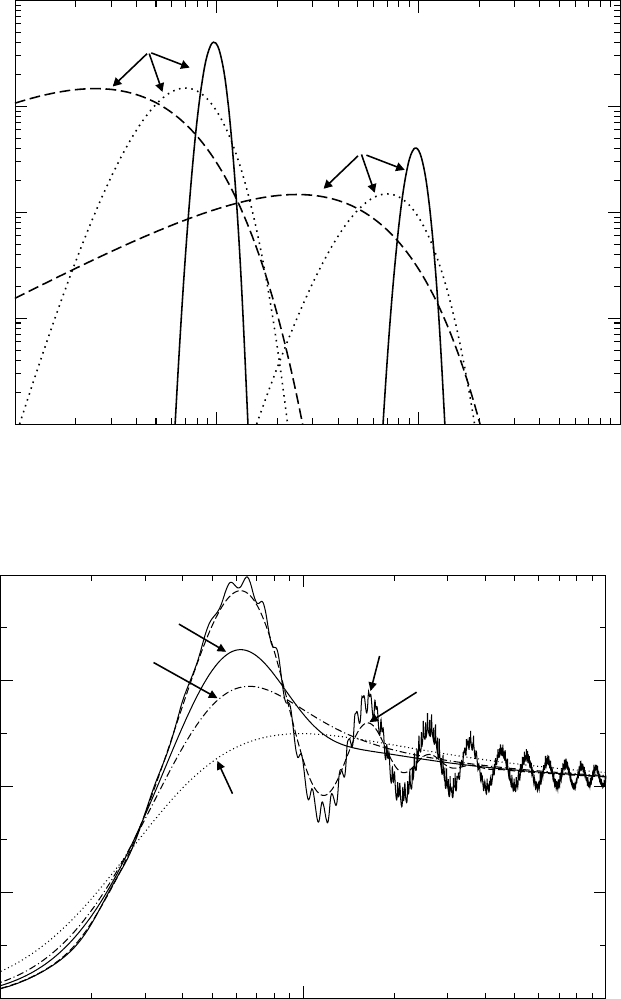

For b = 0.01, 0.1, 0.2 the gamma function appearing in (9.167) assumes the val-

ues 97!, 7!, 2!. To get an impression of the resulting shape of the size distribution, the

normalized form (N =1) cm

−3

is plotted in Figure 9.12 with f (r ) = n(r, N = 1).

Six different distributions are shown, three curves for each a = 1 and a = 10. Two

curves refer to b = 0.01 (solid), two for b = 0.1 (dotted) and finally two curves

for b = 0.2 (dashed). Inspection of the figure shows that the widths of the particle

distribution curves increase with increasing values of b while the heights of the

curves decrease with increasing a.

An application of the cloud droplet distribution function is shown in Figure 9.13

displaying the scattering efficieny factor Q

sca

as a function of the size parameter

x = 2πa/λ. Here a, as defined in (9.169) is the effective radius of the standard

9.7 Selected results from Mie theory 373

0.1 1 10 100

Radius (µm)

0.001

0.01

0.1

1

10

f(r)

a = 1

a = 10

Fig. 9.12 Particle distribution functions for different values of the parameters a

and b.

1 10 100

0

1

2

3

4

Q

sca

b = 0

b = 0.1

b = 0.01

b = 0.5

b = 0.2

x = 2pa/l

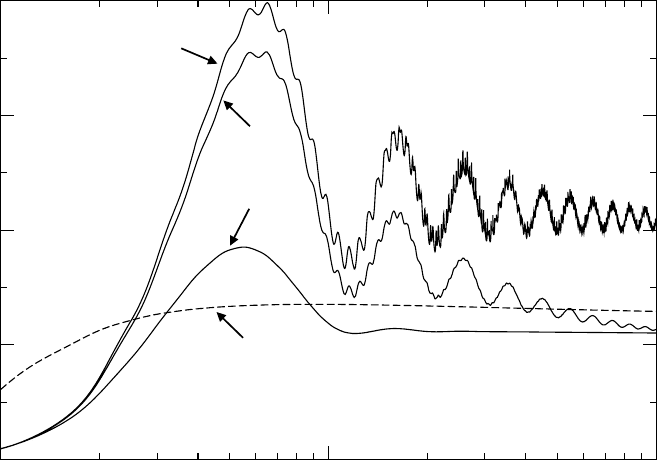

Fig. 9.13 Scattering efficiency factor Q

sca

for various b and the standard modified

gamma distribution function.

374 Light scattering theory for spheres

modified gamma function for N = 1.33 + 0i and b = 0, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5. To

produce this figure, each point on the curve was obtained by first calculating the

efficiency factor for an individual particle and then integrating over the number size

distribution according to

Q

sca

(a, b) =

∞

0

Q

sca

(r)n(r, a, b)dr

∞

0

n(r, a, b)dr

(9.171)

where we have written n(r, a, b) to explicitly show that the particle distribution

function depends on the parameters a and b. A further inspection of the figure

reveals that with increasing b and increasing values of the size parameter x the

ripples, often called the resonances, disappear very quickly even for the rather small

value b = 0.01. Again the limiting value Q

sca

= 2 is obtained for large values of

x. Note that in the present case Q

ext

= Q

sca

since the absorption index has been

chosen to κ = 0. More informations of this type can be found in Hansen and Travis

(1974).

9.8 Solar heating and infrared cooling rates in cloud layers

At this point we have some idea about the behavior of the important efficiency

factors which are needed to evaluate the radiative transfer equation. For a single

particle the extinction, scattering and absorption cross-sections can be calculated

according to (9.132). If the cross-sections refer to unit volume, they are known

as extinction, scattering and absorption coefficients or collectively as attenuation

coefficients. All practical problems involve some sort of a particle size distribution.

The gamma function we have used to specify a particle population is very useful,

but it is by no means the only existing distribution. Let n(r) represent a nonspecified

particle distribution, then the attenuation coefficients are obtained by integrating

the cross-sections over the entire particle spectrum yielding

β

ext,λ

=

∞

0

πr

2

Q

ext,λ

(r)n(r)dr

β

sca,λ

=

∞

0

πr

2

Q

sca,λ

(r)n(r)dr

β

abs,λ

=

∞

0

πr

2

Q

abs,λ

(r)n(r)dr

(9.172)

Since the complex index of refraction, in general, depends on the wavelength, the

efficieny factors Q

ext

, Q

sca

, Q

abs

and thus the attenuation coefficients β

ext

,β

sca

,β

abs

are also wavelength dependent. Application of the wavelength dependent atten-

uation coefficients, in connection with the RTE, results in monochromatic flux