Xing Zh., Zhou Sh. Neutrinos in Particle Physics, Astronomy and Cosmology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

246 6 Neutrinos

f

rom

S

tar

s

A

cker,

A

., and Pakvasa, S., 1994, Ph

y

s. Lett. B

320

, 320.

A

cker, A., Pakvasa, S., and Pantaleone, J., 1991, Ph

y

s. Rev.

D

4

3

,

1754

.

A

harmim, B.,

et al

.

(

SNO Collaboration

)

, 2005, Phys. Rev.

C

7

2

, 055502.

A

harmim

,

B.

,

et al

.

(

SNO Collaboration

)

, 2008, Phys. Rev. Lett.

101

, 111301

.

A

khmedov, E. Kh., 1988, Sov. J. Nucl. Phys.

4

8

,

382

.

A

limonti, G.,

et al.

(

Borexino Collaboration

)

, 2009a, Nucl. Instrum. Meth.

A

6

00

, 568

.

A

limonti, G.,

e

ta

l

. (Borexino Collaboration), 2009b, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A

609

,

58.

A

ltmann

,

M.

,

et a

l.

(

GNO Collaboration

)

, 2000, Phys. Lett.

B

490

,16

.

A

ltmann, M.

,

et a

l.

(

GNO Collaboration), 2005, Phys. Lett.

B

616, 174.

A

lvarez, L. W., 1949, UC Radiation Laboratory Report UCRL-328

.

A

nders

,

E.

,

and Grevesse

,

N.

,

1989

,

Geochim. Cosmochim.

A

ct

a

5

3

,

19

7

.

A

rpesella, C.

,

e

ta

l.

(Borexino Collaboration), 2008, Phys. Rev. Lett

.

1

0

1

,

091302

.

A

s

p

lund, M., Grevesse, N., and Sauval,

A

. J., 2005,

A

SP Conf. Ser. 33

6

,

25.

A

splund, M.

,

et al

., 2009, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.

4

7

,

481

.

B

a

h

ca

ll

, J. N., 1964, P

hy

s. Rev. Lett.

12

, 300

.

B

a

h

ca

ll

, J. N., 1969, P

hy

s. Rev. Lett.

2

3

,

251.

B

ahcall, J. N., 1989,

N

eutrino Astrophysic

s

(Cambridge University Press)

.

B

ahcall, J. N., 1997, Ph

y

s. Rev.

C

56

, 3391.

B

a

h

ca

ll

,J.N.,an

d

Pinsonneau

l

t, M. H., 1995, Rev. Mo

d

.P

hy

s. 67

,

781

.

B

ahcall, J. N., and Ulrich, R. K., 1988, Rev. Mod. Phys

.

6

0

,

297

.

B

ahcall, J. N., Cabibbo, N., and Yahil,

A

., 1972, Ph

y

s. Rev. Lett

.

28

, 316.

B

a

h

ca

ll,

J. N.

,

et a

l.

, 1982, Rev. Mo

d

.P

hy

s. 5

4

,

767.

B

ahcall, J. N.,

et al.

, 1996, Phys. Rev. C

54

,

411.

B

ahcall, J. N., Pinsonneault, M. H., and Basu, S., 2001,

A

stroph

y

s. J

.

555

, 990.

B

ahcall, J. N., Serenelli, A. M., and Basu, S., 2006, Astroph

y

s. J. Suppl.,

1

6

5

,

4

00

.

B

and

y

opadh

y

a

y

,

A

., Choube

y

, S., and Goswami, S., 2003, Ph

y

s. Lett. B

555

,

3

3.

B

arbieri, R.

,

et al

., 1991, Phys. Lett. B

259

,

119

.

B

asu, S., and

A

ntia, H. M., 2008, Ph

y

s. Rept

.

457

,

21

7.

B

asu

,

S.

,

et a

l.

, 2007, Astroph

y

s. J. 655

,

660.

B

eacom, J. F., and Bell, N. F., 2002, Phys. Rev. D

65

,

113009

.

B

ellini

,G

.

,

et a

l.

(

Borexino Collaboration

)

, 2010a, Phys. Rev.

D

8

2

, 033006.

B

ellini, G., et a

l.

(Borexino Collaboration), 2010b, Phys. Lett. B

6

8

7

, 299.

B

ethe, H. A., 1939, Phys. Rev

.

55

,

4

3

4.

B

et

h

e

,

H.

,

an

d

Peier

l

s

,

R.

,

1934

,

Natur

e

13

3

, 532

.

B

iermann, L., 1951, Z. Astrophys

.

2

8

,

304.

B

oger,

J

.,

et al

.

(

SNO Collaboration

)

, 2000, Nucl. Instrum. Meth.

A

449

,1

7

2.

B

¨ohm-Vitense, E., 1958, Z.

A

stroph

y

s.

4

6

, 108.

C

arroll, B. W., and Ostlie, D. A., 2007

,

A

n Introduction to Modern Astrophysic

s

(

Pearson Education, Inc.

)

.

C

handrasekhar

,S

.

,

1938

,

A

n Introduction to the Stud

y

o

f

Stellar Structur

e

(

The

U

niversity of Chicago Press

)

.

C

ha

p

lin, W. J.

,

et al

., 2007,

A

stroph

y

s. J

.

670

,

8

7

2.

R

e

f

erences 24

7

C

hikashi

g

e, Y., Mohapatra, R. N., and Peccei, R. D., 1981, Phys. Lett. B

98

,

2

65.

C

isneros, A., 1971, Astrophys. Space Sci.

10

,

87.

C

leveland

,

B. T.

,

et al.

(

Homestake Collaboration

)

, 1998, Astrophys. J

.

496

,

5

05.

C

owan,

C

. L., Jr.,

et al.

, 1956,

S

cienc

e

124

,

103

.

C

ox

,

J. P.

,

and

G

iuli

,

R. T.

,

1968

,

Principles o

fS

tellar

S

tructure: Ph

y

sical

P

rincip

l

e

s

(

Gordon and Breach, Science Publishers, Inc.).

C

ravens, J. P.,

et al

.

(

Super-Kamiokande Collaboration

)

, 2008, Phys. Rev.

D

7

8

, 032002.

D

avis, R. Jr., 1964, Phys. Rev. Lett

.

12, 303.

D

avis, R. Jr., 1994, Prog. Part. Nuc

l

.P

h

ys

.

32

,

13.

Eg

uc

h

i, K., et a

l

.

(

KamLAND Collaboration

)

, 2003, Phys. Rev. Lett. 90

, 021802

.

E

guchi, K., et a

l

.

(

KamLAND Collaboration), 2004, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92

,

071301.

F

u

k

u

d

a

,

Y.

,

et al.

(

Kamiokande Collaboration

)

, 1996, Phys. Rev. Lett.

77

, 1683.

F

ukuda

,S

.

,

et a

l

.

(

Super-Kamiokande Collaboration

)

, 2003, Nucl. Instrum.

Met

h.

A

5

0

1

, 418

.

G

amow,

G

., 1928, Z. Ph

y

s

.

51

,

20

4.

G

amow,

G

., and

S

choenber

g

, M., 1940, Phys. Rev

.

5

8

,

1117

.

G

amow, G., and Schoenberg, M., 1941, Phys. Rev

.

5

9

,

339

.

G

elmini,

G

. B., and Roncadelli, M., 1981, Ph

y

s. Lett.

B

99

,4

11.

G

iunti

,C

.

,

and Kim

,C

.W.

,

2007

,

F

undamentals o

f

Neutrino Ph

y

sics and

A

s

-

t

rop

h

ysic

s

(Oxford University Press).

G

onzalez-

G

arcia, M.

C

., and Maltoni, M., 2008, Ph

y

s. Rept.

460

,1.

G

revesse

,

N.

,

and Noels

,A

.

,

1993

,

i

n

O

ri

g

in and Evolution o

f

the Elements

(

edited by Prantzos, N., Vangioni-Flam, E., and Casse, M.

)

, p. 14.

G

revesse, N., and Sauval,

A

. J., 1998, S

p

ace Sci. Rev

.

85

, 161.

G

ribov, V. N., and Pontecorvo, B., 1969, Ph

y

s. Lett.

B

2

8

,

493.

H

ampel, W.,

et al.

(

GALLEX Collaboration

)

, 1999, Phys. Lett. B

4

4

7

,

127

.

H

osa

k

a

,

J.

,

et al

.

(

Super-Kamiokande Collaboration

)

, 2006, Phys. Rev. D

73

,

1

12001.

J

oshipura, A. S., Masso, E., and Mohanty, S., 2002, Phys. Rev. D

66

, 113008.

K

aet

h

er

,

F.

,

et al

., 2010, P

hy

s. Lett. B

685

,4

7.

K

lein, J. R., 2008, J. Ph

y

s Conf. Ser

.

136

,

022004

.

K

risciunas, K., 2001, arXiv:astro-ph

/

0106313.

K

uo, T. K., an

d

Panta

l

eone, J., 1989, Rev. Mo

d

.P

hy

s.

6

1

,

93

7

.

K

uzmin, V. A., 1966, Sov. Phys. JETP 2

2

, 1051.

L

andau, L. D., and Li

f

shitz, E. M., 1984

,

E

lectrodynamics o

fC

ontinuous Medi

a

(

Pergamon Press

).

L

im, C. S., and Marciano, W. J., 1988, Phys. Rev.

D

37

,

1368

.

L

odders, K., 2003, Astrophys. J

.

591

,

1220

.

L

odders

,

K.

,

Palme

,

H.

,

and

G

ail

,

H. P.

,

2009

,

arXiv:0901.1149

.

M

cKinsey, D. N., and Coakley, K. J., 2005, Astropart. Phys

.

2

2

,

355

.

M

ikheyev, S., and Smirnov, A. Yu., 1985, Sov. J. Nucl. Phys

.

42

,

913

.

M

ikhe

y

ev, S., and Smirnov,

A

. Yu., 1986, Nuovo Cim.

C

9

,

1

7.

M

iranda, O. G.

,

et a

l.

, 2004, Phys. Rev. Lett

.

9

3

, 051304.

M

o

h

r, P. J., Ta

yl

or, B. N., an

d

Newe

ll

, D. B., 2007, P

hy

s. To

d

a

y

60

,52

.

M

o

h

r, P. J., Ta

yl

or, B. N., an

d

Newe

ll

, D. B., 2008, Rev. Mo

d

.P

hy

s. 8

0

,

633.

248 6 Neutrinos

f

rom

S

tar

s

N

a

k

amura

,

K.

,

et al.

(

Particle Data Group

)

, 2010, J. Phys. G

37

,

0

7

5021

.

P

ena-Gara

y

, C., and Serenelli, A. M., 2008, arXiv:0811.2424

.

P

erryman, M. A. C.

,

et al.

, 1997, Astron. Astrophys.

323

,L49

.

P

ontecorvo, B., 1946,

C

halk River Re

p

ort PD-205

.

P

rialnik, D., 2000

,

A

n Introduction to the Theory of Stellar Structure and Evo

-

lution

(

Cambridge University Press

)

.

P

u

l

i

d

o, J., 1992, P

hy

s. Rept

.

2

11

,

16

7.

R

affelt, G. G., 1996,

S

tars as Laboratories for Fundamental Physic

s

(

The Uni

-

versity of Chicago Press

).

R

affelt, G. G., and Rodejohann, W., 1999, arXiv:hep-ph

/

9912397

.

S

alaris, M., and Cassisi, S., 2005,

E

volution of Stars and Stellar Population

s

(

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

)

.

S

erenelli,

A

. M., 2010,

A

stroph

y

s. Space Sci. 32

8

,13

.

S

erenelli, A. M., et a

l.

, 2009, Astrophys. J. 705, L123

.

V

itense, E., 1953, Z.

A

stroph

y

s

.

32

, 135.

V

oloshin, M. B., and V

y

sotskii, M. I., 1986,

S

ov.J.Nucl.Ph

y

s. 44

,

544

.

V

oloshin, M. B., Vysotskii, M. I., and Okun, L. B., 1986a, Sov. J. Nucl. Phys.

44

,44

0

.

V

oloshin, M. B., V

y

sotskii, M. I., and

O

kun, L. B., 1986b,

S

ov. Ph

y

s. JET

P

64

,

44

6

.

W

einber

g

,

S

., 1972, Gravitation and Cosmolo

gy

: Principles and

A

pplications o

f

t

he

G

eneral Theor

y

o

f

Relativit

y

(

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

)

.

W

einberg, S., 2008, Cosmology

(

Oxford University Press)

.

W

ol

f

enstein, L., 1978, Ph

y

s. Rev. D 1

7

, 2369

.

Y

an

g

,

S

.B.,et a

l

.

(

Super-Kamiokande Collaboration

)

, 2009, arXiv:0909.5469

.

7

N

eutrinos

f

rom Supernovae

The discovery of neutrinos emitted from the Supernova 1987A

(

SN 1987A

)

exp

l

osionisanoutstan

d

ing mi

l

estone in

b

ot

h

neutrino p

h

ysics an

d

neutrino

a

stronom

y

.

O

n the one hand, this

f

ortunate observation o

f

supernova neutri-

n

os provides a stron

g

support for the modern theory of supernova explosions.

On the other hand, it implies that there exists another class of astrophysi-

c

al neutrino sources or astroph

y

sical laboratories.

A

part of this chapter is

to introduce the standard

p

icture of core-colla

p

se su

p

ernovae and

p

roduction

m

echanisms of supernova neutrinos. After a brief account of the experimenta

l

d

etection of the neutrino burst from the SN 1987

A

, we shall explore its impli-

c

ations on neutrino masses and neutrino lifetimes. The flavor conversions of

s

upernova neutrinos, including the effects of collective neutrino oscillations,

w

ill

be d

i

scussed

in

deta

il

.

7

.1

S

tellar

C

ore

C

ollapses and

S

upernova Neutrino

s

The evolution and fate of stars depend crucially on their initial masses. Th

e

reason is simply that the sel

f

-

g

ravity o

f

stars should be balanced by the pres

-

s

ure force to maintain h

y

drostatic equilibrium. For main-sequence stars, ther

-

m

al nuclear reactions serve as the energy source and offer the desired pressure

f

orce. In this section we shall consider the thermal pressure

f

rom de

g

enerat

e

electrons or neutrons. This is the case for white dwarfs and neutron stars

,

which have burnt out nuclear fuels at the final stage of stellar evolution. After

d

iscussin

g

t

h

ee

l

ectron

d

e

g

eneracy pressure, we s

h

a

ll

s

h

ow t

h

at t

h

e

d

e

g

en

-

erate stellar core becomes unstable and colla

p

ses when its mass exceeds the

C

handrasekhar limi

t

M

C

h

∼

1

.

4

M

(

Chandrasekhar, 1931a, 1931b, 1935

)

.

We shall pa

y

particular attention to the core-collapse supernovae which

fi

rs

t

experience the collapse and then rebounce, ejecting the stellar mantle an

d

enve

l

ope an

dl

eavin

g

neutron stars or

bl

ac

kh

o

l

es at t

h

e center. T

h

ero

le

played by neutrinos in the core-collapse supernovae, to

g

ether with possibl

e

m

echanisms of su

p

ernova ex

p

losions, will also be discussed.

Z.-Z. Xing et al., Neutrinos in Particle Physics, Astronomy and Cosmology

© Zhejiang University Press, Hangzhou and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2011

250 7 Neutrinos

f

rom

S

upernovae

7.1.1 Degenerate

S

tars

Fo

r

a

m

ass

i

ve sta

r

w

i

t

h

M

8

M

,

nuclear

f

usion reactions in the cor

e

will continue until the iron-group nuclei

(

e.g.,

56

Fe an

d

56

N

i

)

are abundantly

produced. At this moment the massive star takes on the onion-like structur

e

with an iron core surrounded by the shells of silicon, sulfur, oxy

g

en, neon,

c

arbon and helium from inner layers to outer layers. Since iron is the most

ti

g

htly bound nucleus, no

f

usion reactions can take place.

S

othetherma

l

p

ressure from fusion reactions is not available and the core will contract under

i

ts self-gravity. This contraction ceases if the iron core becomes degenerate

a

nd the de

g

eneracy pressure o

f

electrons is hi

g

henou

g

h to support the wei

g

ht

of the core. White dwarfs result from the stars that are not sufficientl

y

massiv

e

to ignite car

b

on an

d

oxygen in t

h

e core, an

d

t

h

e gravity is

b

a

l

ance

db

y

the pressure from degenerate electrons

(

Liebert, 1980; Chandrasekhar, 1984

;

K

oester and Chanmugan, 1990; Hansen and Liebert, 2003

)

.

Now let us consider a degenerate gas of electrons at the temperature of

a

bsolute zero

(

i.e.,

T

=

0

)

. Due to the Pauli exclusion principle, all the state

s

with momenta ranging from zero to the Fermi momentu

m

p

F

a

re occu

p

ied

.

S

ince the density o

f

quantum states in the momentum space is d

3

p

/

(

2

π

)

3

,

t

h

e tota

ln

u

m

be

r

of e

l

ect

r

o

n

s

in

t

h

ese states

r

eads

N

e

N

=

2

V

p

F

0

4

π

p

π

2

d

p

d

(2

π

)

3

=

Vp

3

F

3

π

2

,

(

7.1

)

where the

f

actor 2 takes account o

f

the spin states an

d

V

i

st

h

evo

l

u

m

eof

the s

y

stem. Hence

p

F

is determined b

y

the number densit

y

of electron

s

n

e

≡

N

e

N

/

V ; i.e.

,

p

F

=(3

π

2

n

e

)

1

/

3

.T

h

e correspon

d

ing Fermi energy

ε

F

≡

p

2

F

/

(

2

m

e

)

f

or non-relativistic electrons is

g

iven b

y

ε

F

=(3

π

2

n

e

)

2

/

3

/

(

2

m

e

)

. Multiplying

the integrand in Eq.

(

7.1

)

b

y

p

2

/

(

2m

e

)

and performing the integration ove

r

t

h

e momentum, we can o

b

tain t

h

e tota

l

energ

y

E

o

f this system. The latter

i

s related to the pressure as follows

(

Landau and Lifshitz, 1980

)

:

P

=

2

E

3

V

=

(

3

π

2

)

2

/

3

5

m

e

n

5

/

3

e

.

(

7.2

)

This e

q

uation of state is also valid for nonzero tem

p

eratures, but the conditio

n

f

or strong degeneracy T

ε

F

s

hould be satisfied. As the gas of degenerate

electrons is compressed, the density increases, so does the mean ener

g

y. In

this case one should consider the relativistic effects i

f

ε

F

becomes much larger

than

m

e

.

The Fermi ener

g

yo

f

relativistic electrons is

g

iven as

ε

F

=

p

F

=

(

3

π

2

n

e

)

1

/

3

.

Multiplying the integrand in Eq.

(

7.1

)

b

y

ε

=

p

and inte

g

ratin

g

over the momentum, we arrive at

(

Landau and Lifshitz, 1980

)

P

=

E

3

V

=

(3

π

)

2

/

3

4

n

4

/

3

e

.

(

7.3

)

The system consistin

g

o

f

only de

g

enerate electrons is actually unstable, so th

e

positively charged nuclei must be present to balance the negative charges of

7

.1

S

tellar

C

ore

C

ollapses and

S

upernova Neutrinos 25

1

electrons. However, the de

g

eneracy pressure

f

rom electrons is dominant ove

r

the thermal

p

ressure of the nuclei. The latter is henceforth assumed to hav

e

n

o impact on the equation of state of the whole system. The number densit

y

o

f

electrons is

g

iven b

y

n

e

=

ρ

/

(˜

μ

e

m

H

), where ˜

μ

e

a

n

d

m

H

s

tan

d

respective

ly

f

or the mean molecular wei

g

ht per electron and the atomic mass unit. Wit

h

the help of Eqs.

(

7.2

)

and

(

7.3

)

, we may rewrite the equation of state a

s

P

=

K

i

K

ρ

γ

(

fo

r

i

=1

,

2

)

,

(

7.4

)

i

n

wh

i

ch

K

1

=(

3

π

2

)

2

/

3

/

[

5

m

e

(˜

μ

e

m

H

)

5

/

3

]

with

γ

=5

/

3

f

or non-relativistic

electrons

,

and

K

2

=(3

π

2

)

2

/

3

/

[4(˜

μ

e

m

H

)

4

/

3

]

with γ

=

4

/

3

for extremel

y

rel

-

ativistic electrons. One always has ˜

μ

e

≈ 2 for heavy nuclei, and thus the

c

orrespon

d

in

g

K

1

a

n

d

K

2

a

re independent of the density. Note that Eq.

(

7.4

)

i

s

j

ust the equation of state for the pol

y

tropic process with the index

n

de

-

fi

ned b

y

γ

=

1

+

1

/n

.

So one may solve Eq.

(

6.12

)

for hydrostatic equilibrium

with the help of Eqs.

(

6.13

)

and

(

7.4

)

. The resultant second-order differentia

l

equation for the density is

(

Prialnik, 2000

)

(

n

+

1

)

K

4

π

G

N

n

·

1

r

2

·

d

d

r

r

2

ρ

(

n

−

1

)

/n

·

d

ρ

d

r

=

−

ρ,

(

7.5

)

whe

r

e

K

=

K

1

for

n

=3

/

2

a

n

d

K

=

K

2

for

n

=

3. T

h

e

d

ensit

yd

istri

b

ution

ρ

(

r

)

for 0

r

R should fulfill the initial condition

s

ρ

(

R

)

=0

(

wit

h

R

being the radius of the star

)

and

d

ρ

d

r

=

0 at the center. These conditions

f

ollow from the equation of state and the pressure profile wit

h

P

(

R

)

=0an

d

d

P

d

r

=0

at

r

=

0. After a change of variable

s

ρ

=

ρ

c

Θ

n

a

n

d

r

=

α

ξ

,

w

h

er

e

α

≡

{

(

n

+1

)

K

/

4

π

G

N

ρ

(

n

−

1)

/

n

c

}

1

/

2

a

n

d

ρ

c

i

st

h

e centra

ld

ensity, we o

b

tai

n

the Lane-Emden e

q

uation o

f

inde

x

n

(

Chandrasekhar, 1938; Prialnik, 2000

):

1

ξ

2

·

d

d

ξ

ξ

2

d

Θ

d

ξ

=

−

Θ

n

(

7.6

)

wit

h

t

h

e correspon

d

in

g

initia

l

con

d

ition

s

Θ

=

1

a

n

d

d

Θ

d

ξ

=0

at

ξ

=

0

.

In general, Eq.

(

7.6

)

can be numerically solved. It has been found tha

t

Θ

d

ecreases monotonically to zero at a finit

e

ξ

=

ξ

R

f

or

n

<

5

(

Shapiro and

Teukolsky, 1983

)

. Note tha

t

Θ

(

ξ

R

)

= 0 corresponds to

ρ

=

0atthesur

f

ac

e

of the star. Hence the radius and the mass of the star are given by

(

Shapiro

a

nd Teukolsky, 1983

)

R

=

αξ

R

=

ρ

(1

−

n

)

/

2

n

c

ξ

R

(

n

+1

)

K

4

π

G

N

1

/

2

,

(

7.7

)

a

nd

252 7 Neutrinos

f

rom

S

upernovae

M

=

R

0

4

π

r

2

ρ

(

r

)

dr

=4

π

ρ

(

3

−

n

)

/

2

n

c

ξ

2

R

(

n

+

1

)

K

4

π

G

N

3

/

2

d

Θ

d

ξ

ξ

=

ξ

R

,

(

7.8

)

where Eq.

(

7.6

)

has been used to evaluate the integration. Eliminatin

g

ρ

c

in

E

qs.

(

7.7

)

and

(

7.8

)

, we get an interesting mass-radius relatio

n

M∝

R

(3

−

n

)

/

(1

−

n

)

,

(

7.9

)

i

mplyin

g

that

M

∝ R

−

3

f

or

n

=3

/

2. More interestin

g

ly, the mas

s

M

i

s

i

ndependent o

f

R

an

d

ρ

c

fo

r

n

=

3

.Int

h

is case a mass

l

imit must exis

t

as

ρ

c

→∞

a

n

d

R

→

0.

S

ubstitutin

g

n

=

3,

K

=

K

2

,

ξ

R

≈

6

.

897

an

d

d

Θ

d

ξ

ξ

=

ξ

R

=0

.

0

424 into Eq.

(

7.8

)

, one gets the Chandrasekhar mass limit

M

Ch

≈

5

.

7˜

μ

−

2

e

M

≈

1

.

4

M

for ˜

μ

e

=2

(

Chandrasekhar, 1931a, 1931b

,

1

935

)

. The existence of such a mass limit can be understood in an intuitiv

e

way, which was first presented by Lev Landau

(

Landau, 1932; Shapiro and

Teukolsky, 1983

)

. For a star with the total baryon numbe

r

N

b

N

N

,

i

ts

g

rav

i

ta

-

tiona

l

potentia

l

energy is given

b

y

E

g

∝

−

G

N

N

b

N

N

R

−

1

.

On the other hand

,

the Fermi ener

g

yo

f

relativistic de

g

enerate electrons is E

F

∝

N

1

/

3

b

NN

R

−

1

.

I

f

N

b

NN

i

s very large

(

i.e., the star is very massive

)

, the total energy

E

=

E

g

+

E

F

c

an be negative and thus decrease without bound as the radiu

s

R

d

ecreases.

A

s a result, a limit o

f

N

b

NN

or

M

=

N

b

NN

m

p

e

xi

sts for

E

=0

(

i.e., the balanc

e

between the gravity and the degeneracy pressure of electrons

).

7.1.2

C

ore-colla

p

se

S

u

p

ernovae

Supernovae are exploding stars that emit a large amount of thermal energy i

n

a

relatively short time

(

e.g., from one year to several days

)

and overshine al

l

the other stars in the host galaxies. They are in general classified as type-I an

d

type-II supernovae, which can be further divided into subclasses

(

e.g., type-Ia,

b, c

)

according to the existence of hydrogen, helium or silicon spectral lines

(

Bethe, 1990

)

. Although the explosion mechanism for type-Ia supernova

e

remains an open question, it is commonly assumed that the ener

g

y

f

ro

m

n

uclear

f

usion reactions accounts

f

or the ex

p

losion. In this case neutrinos

a

re not as important as in the core-collapse type-Ib, type-Ic and type-I

I

s

upernovae, w

h

ere t

h

eexp

l

osion is powere

db

yt

h

e

g

ravitationa

l

potentia

l

ener

g

y and nearly all the ener

g

y is released in the form of neutrinos. We shal

l

c

oncentrate on type-II supernovae in the following

.

As mentioned before, a massive star

(

M

8

M

)

will develop a degener-

a

te iron core at the final sta

g

e of its evolution. Moreover, the silicon-burnin

g

sh

e

ll

wi

ll

continuous

l

y contri

b

ute mass to t

h

e core an

d

eventua

ll

y

l

ea

d

to a

n

excess over the

C

handrasekhar mass limit and thus the

g

ravitational collapse

.

Two other microsco

p

ic

p

rocesses at this moment make the situation worse.

A

s the iron core contracts, the temperature will slightly increase. Hence th

e

7

.1

S

tellar

C

ore

C

ollapses and

S

upernova Neutrinos 253

photodissociation of heavy nuclei

(

e.g.,

γ

+

56

Fe

→

13

4

He + 4

n

−

1

24 MeV

)

becomes more efficient. This endothermic reaction consumes thermal ener-

gies and thus reduces the thermal pressure. On the other hand, the de

-

g

enerate electrons will be captured by heavy nuclei or

f

ree nucleons via

e

−

+

A

(

Z

,

N

)

→

A

(

Z

−

1

,N

+1

)+

ν

e

.

Since neutrinos are weakly interacting

with matter, they will escape from the core immediately after production an

d

take away enormous thermal ener

g

ies. Furthermore, the number o

f

electrons

h

as been diminished such that the degeneracy pressure is accordingly re

-

d

uced. Both the photodissociation of nuclei and the electron-capture process

c

an further reduce the thermal pressure and aggravate the collapse

(

Bethe

,

1

990

;

Janka

,

e

tal

.

,

2007

).

Th

eco

ll

apse is o

b

vious

l

y

d

etermine

db

yt

h

e

g

ravity an

dh

y

d

ro

d

ynamics.

Interestin

g

ly, it has been discovered that the inner part o

f

the iron core col

-

l

apses in a homologous way; i.e., the distribution of temperature and density

i

s similar and only scales with respect to time

(

Goldreich and Weber, 1980

).

F

or the inner core, the velocity o

f

in

f

allin

g

matter is proportional to the ra-

d

ius but smaller than the velocity of sound, while the outer core falls inward

s

upersonically

(

Yahil and Lattimer, 1982; Yahil, 1983

)

. The critical

(

or sonic

)

point can be taken as the position where the infall velocit

y

equals the sound

velocity. Thus the inner core is in good contact with itself, whereas the outer

one is not.

A

s the core collapses, the matter densit

y

in the center reaches

a

nd exceeds the nuclear densit

y

ρ

0

∼

3

×

10

14

g

cm

−

3

.

The nuclear matter i

s

l

ess compressi

bl

ean

d

t

h

e pressure

b

ui

ld

supgra

d

ua

ll

y, so t

h

e gravitationa

l

c

ollapse o

f

the inner core will be hindered. However, the

f

reely-

f

allin

g

outer

part cannot immediatel

y

feel the pressure, so the matter still falls inward. If

the infall velocity ultimately goes to zero, the pressure wave will become

a

s

hock at the large radius just beyond the sonic point

(

Cooperstein and Baron,

1

990; Bethe, 1990

)

. It is expected that such a shock wave will traverse th

e

w

h

o

l

estaran

db

ea

bl

etoexpe

l

t

h

e mant

l

ean

d

enve

l

ope,

g

ivin

g

rise to a

s

upernova

(

Colgate and Johnson, 1960

)

. Meanwhile, a neutron star or blac

k

h

ole remains at the center. But most of the detailed numerical simulations

h

ave not con

fi

rmed this prompt-shock explosion picture. When the shock

wave propa

g

ates outward, it will disassociate heavy nuclei into nucleons a

t

the energy expense of 9 MeV per nucleon. It turns out that the shock wave

s

ta

ll

st

y

pica

lly

at a ra

d

ius a

b

out 400

k

m. W

h

et

h

er t

h

eprompts

h

oc

k

ca

n

s

ucceed or not depends sensitivel

y

on the pre-supernova evolution, such as

the equation of state and the mass of the core

(

Baron

e

ta

l.

, 1985a, 1985b

)

.

U

sually the prompt shock will

f

ail i

f

the mass o

f

the iron core is

g

reater tha

n

1

.

2

5M

(

Arnett, 1983; Hillebrandt, 1982a, 1982b, 1984; Cooperstein

e

tal.

,

1

984; Baron and Cooperstein, 1990

)

.

B

ecause o

f

the

f

ailure o

f

the prompt-shock model, the neutrino transpor

t

m

odel was proposed

(

Colgate and White, 1966

)

and the delayed-shock mode

l

was developed

(

Bowers and Wilson, 1982a, 1982b; Wilson, 1985; Bethe an

d

Wilson, 1985

)

. Neutrinos play a crucial role in this mechanism. When the

254 7 Neutrinos

f

rom

S

upernovae

m

atter densit

y

o

f

the inner core increases to about 1

0

12

g

c

m

−

3

,e

l

ectron

n

eutrinos

(

with energies around 10 MeV

)

resulting from the electron-captur

e

processes will be trapped due to coherent scattering of neutrinos on heav

y

n

uc

l

ei via t

h

eneutra

l

-current interactions. T

h

etrappe

d

e

l

ectron neutrino

s

f

orm a degenerate Fermi sea through the beta equilibrium reactio

n

e

−

+

p

↔

n

+

ν

e

.

Hence t

h

e gravitationa

l

potentia

l

energy

d

uring t

h

eco

ll

apse

h

as

b

ee

n

c

onverted into the chemical potentials o

f

electrons and neutrinos. Neutrinos

d

iffuse out of the core and heat the materials in the region below the stalle

d

s

hock, and ultimately revive the shock and lead to a successful explosio

n

(

Colgate and White, 1966; Bethe and Wilson, 1985

)

. A simulation includin

g

the neutrino transport actually demonstrates that a proper fraction of the

n

eutrino energy could successfully revive the stalled shock

(

Janka and M¨uller,

1

993

)

. However, it is still unclear how neutrinos deposit the right amount o

f

energies and whether the convection and rotation effects are inevitable for a

s

uccessful explosion

(

Janka

et al.

,

2007

).

7.1.3

S

u

p

ernova Neutrinos

A

s pointed out by George Gamow and Mario Schoenberg, neutrinos may

play a crucial role in a collapsing star

(

Gamow and Schoenberg, 1940, 1941

).

In the su

p

ernova context neutrinos can be tra

pp

ed in the core via coherent

n

eutrino-nucleon scattering

(

Freedman, 1974; Mazurek, 1975; Sato, 1975

).

The interactions o

f

neutrinos with the back

g

round nucleons and electron

s

h

ave been systematically studied

(

Tubbs and Schramm, 1975; Lamb an

d

P

et

h

ic

k

, 1976; Bet

h

e

et al

., 1979

)

. The mean free path of neutrinos for elasti

c

s

cattering is given by

(

Bethe

et al

., 1979

)

λ

ν

=1.

0

×

1

0

8

cm

ρ

10

12

g

c

m

−

3

M

e

V

E

ν

2

N

2

6

A

X

h

+

X

n

−

1

,

(

7.10

)

w

h

ere ρ

i

st

h

e matter

d

ensity

,

E

ν

d

enotes t

h

eneutrinoenergy,

X

h

an

d

X

n

represent the mass

f

ractions o

f

heav

y

nuclei and nucleons,

N

a

n

d

A

a

r

ethe

n

umbers of neutrons and nucleons in an avera

g

e nucleus. We have taken

s

i

n

2

θ

w

=1

/

4 in obtaining Eq.

(

7.10

)

. The contribution from neutral-curren

t

i

nteractions of neutrinos with protons, which is proportional to

(1

−

4s

i

n

2

θ

w

),

i

s therefore vanishing. Taking

X

h

≈

1

and

X

n

≈

0 during the infall phase, one

obta

in

s

λ

ν

≈

2

km f

o

r E

ν

=

10

M

e

V

,

ρ

=10

12

gc

m

−

3

,

N

≈

50

an

d

N

/

A

=

0

.

6(

Bethe, 1990

)

. The radius of the core corresponding t

o

ρ

=10

12

g

c

m

−

3

i

sabou

t

R

=

30 km, and hence neutrinos are essentiall

y

trapped in the core

a

nd can only get out of it by diffusion

(

Cooperstein, 1988a, 1988b

)

.

A

fter bein

g

trapped, the electron neutrinos come into chemical equilib

-

rium with the degenerate electrons and nucleons through the beta process

e

−

+

p

↔

ν

e

+

n

.There

f

ore, a de

g

enerate Fermi sea o

f

neutrinos builds up

,

a

nd the correspondin

g

chemical potential is determined b

y

μ

ν

e

=

μ

e

−

ˆ

μ

w

i

th

ˆ

μ

≡

μ

n

−

μ

p

≈

100 MeV. The chemical potential of degenerate electron

s

7

.1

S

tellar

C

ore

C

ollapses and

S

upernova Neutrinos 255

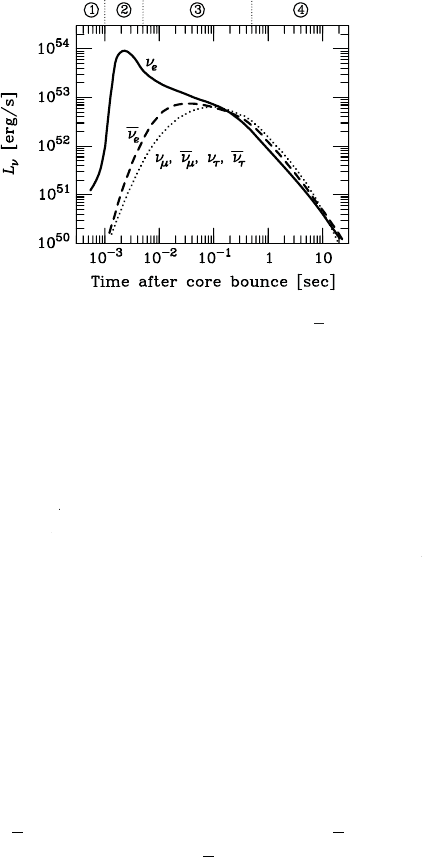

Fi

g

. 7.1 Luminosities o

f

neutrino

s

ν

α

an

d

antineutrinos

ν

α

(

for

α

=

e

,

μ

,

τ

)

versus

the time after the core bounce. Four stages of the delayed-explosion scenario are

shown

(

Raffelt, 1996. With permission from the University of Chicago Press

)

:

(

1

)

the collapse and bounce;

(

2

)

the shock propagation and prompt neutrino burst;

(

3) the matter accretion and mantle cooling while the shock stalls; (4) the Kelvin-

Helmholtz cooling o

f

the neutron star a

f

ter explosio

n

is

μ

e

≈

111 MeV

(

ρ

13

Y

e

YY

)

1

/

3

,

where

ρ

13

denotes the matter densit

y

in units

of 1

0

13

g

cm

−

3

a

n

d

Y

e

YY

is the number fraction of electrons. For the nuclea

r

d

ensit

y

ρ

0

=

3

×

10

14

g

c

m

−

3

and a t

y

pical electron

f

raction

Y

e

YY

=0

.

4

,w

e

h

av

e

μ

e

≈

2

50 MeV an

d

μ

ν

e

≈

1

50 MeV

(

Bethe, 1990

)

. Hence the gravi

-

tationa

l

potentia

l

energy re

l

ease

dd

uring t

h

eco

ll

apse

h

as

b

een

l

arge

l

ycon

-

verted into the chemical potentials o

f

de

g

enerate electrons and neutrinos

.

Shortly after the bounce, the shock wave disassociates the infalling heavy

n

uclei into free nucleons, on which the electron-capture rate is much larger

.

O

n the other hand, the matter density in the re

g

ion just below the shoc

k

wave has been dramatically reduced, allowing the electron neutrinos to freel

y

escape. T

h

is is t

h

eso-ca

ll

e

d

prompt neutronization or

d

e

l

eptonization

b

urs

t

o

f

neutrinos. The electron ca

p

ture and the neutrino burst lead to a moderate

reduction of the le

p

ton number in the iron core. As a conse

q

uence, the neutri-

n

os o

f

all

fl

avors can now be produced via the electron-positron annihilation

e

+

+

e

−

→

ν

α

+

ν

α

,

the plasmon deca

ys

γ

∗

→

ν

α

+

ν

α

and the nucleonic

b

remsstra

hl

ung

N

+

N

→

N

+

N

+

ν

α

+

ν

α

(

Suzuki, 1991, 1993

)

. For illustra-

tion, the neutrino luminosit

yf

rom the standard dela

y

ed-explosion scenario i

s

s

hown in Fi

g

. 7.1, where one can see the hi

g

hly-peaked neutrino burst and

the approximate equilibration of neutrino luminosities at later times. Note

t

h

at t

h

eneutrino

l

uminosities are

d

epen

d

ent on t

h

etime.

S

imilar to electron neutrinos, muon and tau neutrinos are also tra

pp

ed

a

nd keep in local thermal equilibrium with electrons and nucleons. They dif-

f

use outward to their respective neutrino spheres,

f

rom which the

y

ma

yf

reel

y

escape. Hence the energy spectra of neutrinos can be well described by th

e