Woodard R.D. (editor) The Ancient Languages of Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

continental celtic

167

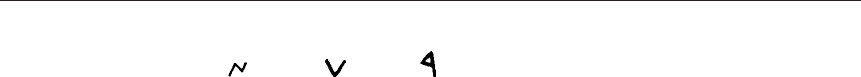

(1) The alternative nasal and rhotic sets

´

m

´

n

r

There are a number of points to be noted about the mechanics of the script. There were

two geographic zones which employed differing sets of characters to write the nasals. Broadly

speaking, <

´

m> and <

´

n> were employed in the west, <m> and <n> in the east. Nasals

are sometimes not written before stops; it is probable that this represents the transference of

nasality to a preceding vowel (see Eska 2002a). The character <r> is attested only in some

late coin legends; it does not contrast with <

´

r>. It now seems clear that <

´

s> represents

PIE

∗

s unchanged whereas <s> represents

∗

s in voiced environments and

∗

d in certain

medial environments and in final position. Some scholars, therefore, elect to transcribe s

as <z> or <

> (and hence then elect to transcribe  as <s> instead of traditional <

´

s>).

It is not yet clear whether this character represents more than one sound (or phoneme).

Geminate consonants are written as single. The sequence <ei> is employed to write the

inherited diphthong ei, and sometimes e from unstressed

∗

i (perhaps phonetically a raised

[e]), as well as the phoneme which continues PIE

∗

¯e in final syllables, which eventually

became ¯ı (perhaps phonetically a lowered [i:]).

Owing to the moraic quality of the stop characters, stop + liquid groups are difficult to

represent. A variety of solutions are found, as listed in (2):

(2) A. An empty vowel (having no phonetic reality) may be written which copies the

quality of the following phonemic vowel: e.g., enTa´ra /entra:/

B. The liquid and following phonemic vowel may be metathesized orthographically:

e.g., ConTe´rPia /kontrebia:/

C. The liquid may be elided orthographically: e.g., ConPouTo /konblowto/

The moraic quality of the stop characters also makes it difficult to determine the manner

in which final stops were written; for example, it is unclear whether the third singular

primary ending

∗

-ti is continued intact or with the vowel apocopated in the verbal form

a´seCaTi. Owing to the influence of the segmental character of the Roman script, but prior

to its adoption, syllabic characters came to be followed by a separate character denoting

the inherent vowel: for example, in ´mo´niTuuCoo´s. On the use of empty vowels in the Celtic

adaptation of the script, see De Bernardo Stempel (1996).

The origin of the Iberian script, which was deciphered by G

´

omez-Moreno (1922), remains

a subject of debate (see de Hoz 1983). While it is agreed that there are Phoenician and Greek

elements underlying the script, it is uncertain whether they were integrated simultaneously

or whether an original script based upon one was renewed with elements of the other.

2.2 Lepontic

The entirety of the Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish corpora are engraved in variants of

the north Etruscan script. The script is segmental, but shares various features of the Iberian

script. Neither the voicing of stops nor the quantity of vowels is noted. Nasals are rarely noted

before stops; as with this feature in Hispano-Celtic, in which it is sporadic, it is probable that

this represents the transference of nasality to a preceding vowel (see Uhlich 1999:280 and

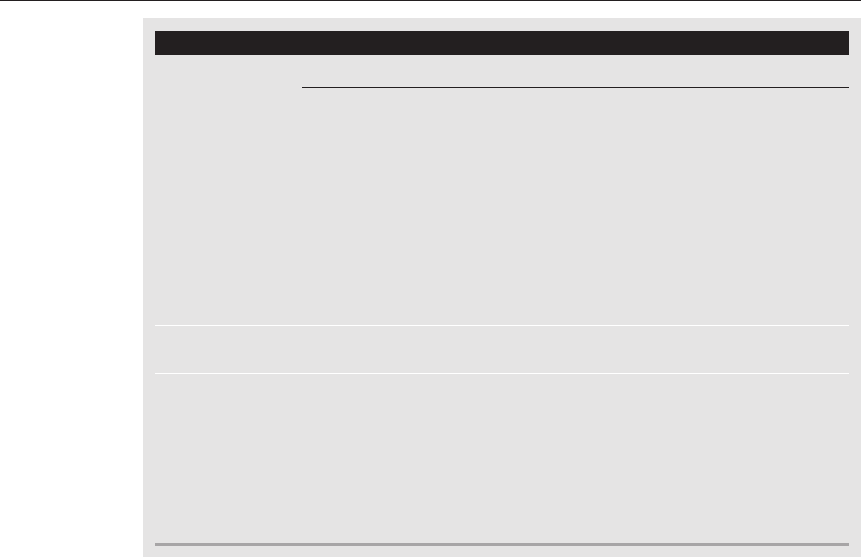

293 and Eska 2002b: 263–269). Table 35.2, adapted after De Marinis (1991:94), records the

Lugano script, in which the corpus is engraved. See further Lejeune (1971:8–27; 1988:3–8).

The infrequently attested characters <χ> and <θ> were inserted into the script in order

to introduce a voicing distinction for the dental and velar stops. Whether the new character

168 The Ancient Languages of Europe

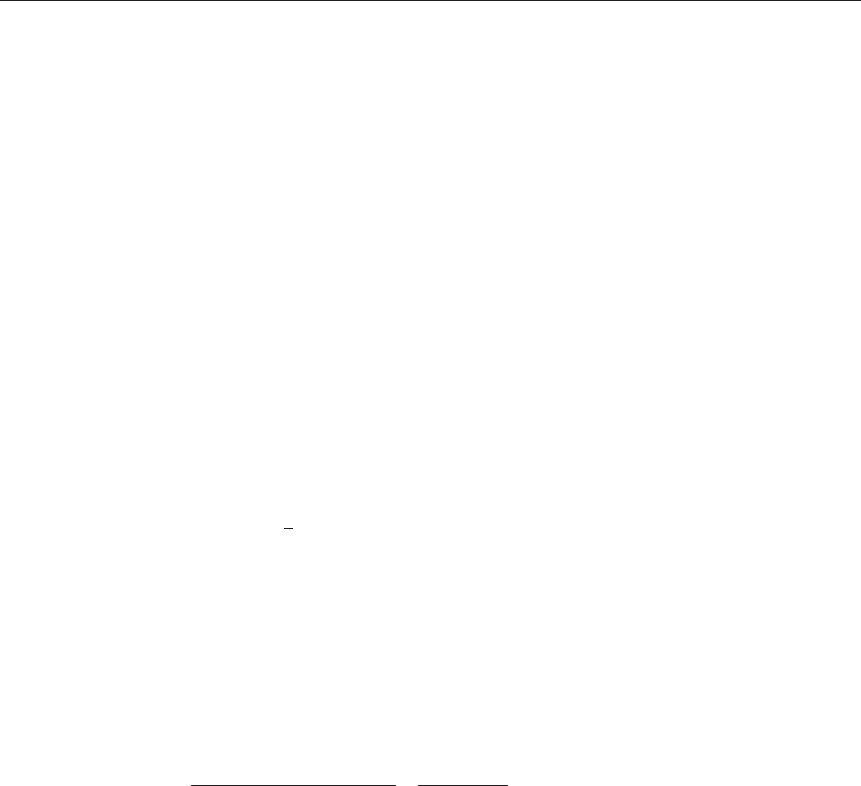

Table 8.2 The Lugano script

6–5 Centuries Transcription 3–2 Centuries

a

e

v—

z

h—

—

i

K

l

m

n

P

´

s

r

s

T

u

o

represents the voiceless or voiced stop varies among inscriptions. The phonetic value of

the character <v> has been much disputed, but may well represent /φ/fromPIE

∗

p;see

Eska (1998a). The character <

´

s> and the twice attested <z> represent a sound (or two

acoustically similar sounds) known as the tau Gallicum (see §3.3.1.1).

2.3 Gaulish in Greek characters

Prior to the Roman conquest of Transalpine Gaul, the Massiliote Greek script was employed

to write in Gaulish. Noteworthy orthographic features of Greek-character Gaulish are the

use of the digraph <> for Roman <u> and <v>, and the occasional use of <> for

<>, <> for <>, and <> for <o> (i.e., long-vowel graphemes for short vowels). The

tau Gallicum sound (see §3.3.1.1) is variously written: <

θ, θθ, , , , , θ>. See further

Lejeune (1985:427–434, 441–446).

2.4 Gaulish in Roman characters

Gaulish was engraved in Roman characters in both capitals and cursive script with the

expected values. The i-longa is frequently attested, but it does not seem to be differentiated

in value from <i>; it is now conventionally transcribed as <j>.Thetau Gallicum sound

(see §3.3.1.1) is written with a wide variety of mono-, di-, and trigraphs: <t, tt, th, tth, d, dd,

√, √√, ts, ds, s, ss, ss

, sc, sd, st>. In some later Gaulish inscriptions, the appearance of final

<-m> has been attributed to Roman influence (i.e., perhaps the engraver was principally a

Latin speaker).

continental celtic

169

3. PHONOLOGY

Since the Continental Celtic languages are not only fragmentarily attested, but also often

engraved in scripts which are phonologically ill-suited to them, it is difficult to estab-

lish complete phonemic inventories. It is often necessary to rely upon Indo-European

and Insular Celtic etymologies to determine the expected phonology of a form. Readers

should keep in mind that the descriptions presented in this and subsequent sections may be

incomplete.

3.1 Hispano-Celtic

3.1.1 Consonants

The consonantal phonemic inventory of Hispano-Celtic is as follows:

(3) Hispano-Celtic consonantal phonemes

tkk

w

bd

w

mn

s

l

r

yw

The sound represented by the character <s> (NB that /s/ is represented by <

´

s>), whose

status as a phoneme remains to be determined, is not included in (3). Phonetic values for it

that have been suggested include the fricatives [z] or [

ð] (Villar 1995a:65–82) and affricates

[t

s

]or[d

z

] (Ballester 1993–1995).

3.1.2 Vowels

The monophthongs and diphthongs of Hispano-Celtic are listed in (4):

(4) Hispano-Celtic vocalic phonemes

Monophthongs Diphthongs

i

¯

ıu

¯

uaiau

e

¯

eo eieu

a

¯

aoiou

It is possible, but uncertain, that PIE

∗

¯e is preserved in unstressed syllables; the element -´re´s,

which is normally assumed to continue

∗

h

3

r¯e©s “king,” occurs several times as the second

member of compound forms. Elsewhere, PIE

∗

¯e has been raised to merge, at least phonem-

ically, with ¯ı. In some later inscriptions, PIE

∗

ei has been monophthongized to ¯e. A gap in

the vowel system was caused by the raising of PIE

∗

¯o to ¯u in mono- and final syllables and its

lowering to ¯a elsewhere. Unstressed

∗

i has a tendency to be lowered to e: for example, a´re-

“fore-” from

∗

p‰h

x

í-.

170 The Ancient Languages of Europe

3.1.3 Consonant clusters

Groups of stop + s are routinely written as <

´

s>, which suggests that such groups assimilated

to -ss-. The group ks appears to have sometimes been preserved, however, at least to judge

from Roman character spellings which employ the character <x>. The inherited group

∗

ln also assimilates to ll. Other groups are generally preserved. Noteworthy is the fact that

nasals do not always assimilate to the place of following stops, for example TinPiTus from

∗

d

ˇ

¯e-en-b-. The form ConPouTo is peculiar since the basic form of the prefix is kom- (but see

now Eska 2002a: passim).

3.2 Lepontic

3.2.1 Consonants

The consonantal inventory of Lepontic is set out in (5):

(5) Lepontic consonantal phonemes

(φ/)p t k (k

w

)

bd

(

w

)

mn

s

l

r

yw

The sound(s) spelled by the characters <

´

s> and <z>, usually called the tau Gallicum,is

not listed in (5), but is discussed at some length below (see §3.3.1.1). Though it is ordinarily

considered to continue the sequence

∗

ts immediately, <

´

s> is apparently also used to spell

the outcome of the group

∗

-ksy- in the accusative singular na´som, the Lepontic adaptation

of the Greek neuter nominative-accusative adjective (N

´

aksion). It is possible that

early Lepontic continued PIE

∗

p as the bilabial fricative [

φ] and preserved PIE

∗

k

w

in forms

such as Kua´soni; the latter might, however, contain

w

from PIE

wh

.

3.2.2 Vowels

The inventory of Lepontic monophthongs and diphthongs is identical to that of Hispano-

Celtic; see (4). The gap in the vowel system is as with Hispano-Celtic (see §3.1.2). PIE

∗

ei is

preserved in final position, but elsewhere has been monophthongized to ¯e.

3.2.3 Consonant clusters

Consonant groups do not assimilate, save for

∗

-nd- > -nn- and the predecessors of the tau

Gallicum.

3.3 Gaulish

Since the Gaulish corpus is the largest of the Continental Celtic languages and is attested

over the longest chronological period, it is difficult to ascertain a synchronic phonemic

inventory. Readers should be aware that the phonemic inventory presented in (6) and (7) is

a composite.

continental celtic

171

3.3.1 Consonants

The consonantal phonemes of Gaulish appear to be as follows:

(6) Gaulish consonantal phonemes

ptk(k

w

)

bd

mn

s

l

r

yw

The labiovelar k

w

is preserved only in a few archaic forms.

3.3.1.1 Tau Gallicum

The tau Gallicum is not included in (6). Based upon the diversity of graphemes with which

it is written, it is usually assumed to have been a dental affricate, fricative, or sibilant. This is

supported by etymological considerations, as the tau Gallicum often immediately continues

∗

ts and

∗

ds, and ultimately

∗

st (including

∗

st <

∗

tst <

∗

-t-t- and

∗

-d-t-). It is commonly

believed that the most likely phonetic value for it is [t

s

], but other suggestions include [t

θ

],

[

θ](orretracted[θ]), [θs], and [t

h

]. It is usually assumed that the tau Gallicum,evenwhen

written as a di- or trigraph, was a single segment, but in view of the fact that it is cognate

with Insular Celtic -ss-, it is probable that it often was a geminate. The most complete

discussion of the tau Gallicum is that of Evans (1967:410–420), but see also Eska (1998c).

3.3.2 Vowels

The monophthongs and diphthongs of Gaulish are listed in (7):

(7) Gaulish vocalic phonemes

Monophthongs Diphthongs

i

¯

ıu

¯

uaiau

e

¯

eo

¯

oeieu

a

¯

aoiou

The diphthongs ai and eu appear only in older forms; in later forms, ai is contracted to ¯ı and

eu merges with ou, which subsequently contracts to ¯o. The diphthong oi is attested early,

theniscontractedto¯ı; it reemerges later, as does ei (PIE

∗

ei having become ¯e in Gaulish),

as the result of the loss of intervocalic

∗

p and

∗

w. There is a tendency for long diphthongs

to shorten: for example, ¯a-stem dative singular

∗

-¯ai > -ai > ¯ı; and u-stem dative singular

(from the locative)

∗

-o¯u > -ou. Unstressed i frequently is lowered to e: for example,

∗

p‰h

x

í-

“fore-” > are-; and dative or instrumental plural -bi > -be.

3.4 Allophonic variation

Though the Continental Celtic languages – as far as the scripts employed will allow – are

usually written phonemically, occasional quasi-phonetic orthographies occur which provide

some evidence for allophonic variation in Hispano-Celtic and Gaulish.

172 The Ancient Languages of Europe

In Hispano-Celtic, there is a strong tendency towards labialization of o to u when adjacent

to a nonfinal labial: for example, the o-stem dative plural is often written <-uP

´

os> and the

first plural present ending is written <-mu(s)>. That -o- occurs at all may be the product of

phonemic or conservative orthography; but the o-stem accusative singular -om, for example,

is always written with <-o->.

In Gaulish, the velar stop /k/ becomes the fricative [x] before s and t. Mid vowels in

hiatus with non-high vowels tend to be raised: for example, to = me = decla¨ı <

∗

l¯a- +

∗

-e;

compare coetic and cuet[ic], both with prevocalic /ko/-; and /luernios/ <

∗

lo-erno-

<

∗

h

2

lop-erno-.

Hispano-Celtic and Gaulish share a tendency for e to raise to i before nasal + stop

clusters (Gaulish more so). It is presumed that in all of Continental Celtic nasals were

realized as [

ŋ] before velars. This view is supported by Gaulish inscriptions engraved in Greek

characters which employ <> (the Greek grapheme for [

ŋ]), for example,

for [eski

ŋ

ori:ks].

There is substantial evidence for phonetic lenition in both Hispano-Celtic and Gaulish.

In Hispano-Celtic, /s/ = <

´

s> is normally spelled as <s> in voiced environments (perhaps

here being [z]). The clearest evidence for phonetic lenition is provided by genitive singular

TuaTe´ro´s and nominative plural Tua[Te]´r´es <

∗

dugater- <

∗

d

h

u©h

2

ter- “daughter,” which

exhibit the change of [

] > [] > ø. The absence of indication for voicing or manner of

articulation in the Iberian script and the rarity of quasi-phonetic orthography in Roman

character inscriptions conceal any further evidence.

In Gaulish, there are two forms which provide evidence for [s] > ø / V

V: dative or

instrumental plural suiorebe <

∗

swesor- “sister”; and sioxt < 3rd sg. preterite

∗

sesog- + -t

(base

∗

seg- “add”; see Eska 1994c). In later Gaulish, [] also is often deleted intervocalically.

Gaulish is also well known for orthographic variation between <c> and <g> (similar

variation between other homorganic stops is much less common); it remains uncertain

whether this represents phonetic or orthographic variation, though, since the large majority

of tokens involve the substitution of a voiceless for a voiced stop, Gray (1944:227) may be

correct in suspecting that the voiced stop phonemes of Gaulish were phonetically voiceless.

This orthographic variation would then be another type of quasi-phonetic orthography.

There are also several examples in which /t/ in lenited position is engraved with one of the

graphemes employed to write the tau Gallicum (see §3.3.1.1): for example, e

ic (cf. etic)

“and”; gnatha (cf. nata) “daughter”; and bue

(cf. buet) “be” – suggesting that the lenited

allophone of /t/ was either identical, or acoustically similar, to the tau Gallicum consonant.

3.5 Accent

There is little, if any, direct evidence for the placement of stress in any of the Continental

Celtic languages. In Hispano-Celtic, the failure of final -m to labialize a preceding -o-

indicates that it was very weakly articulated, which suggests that the stress may have been

fixed towards the beginning of the word. Likewise, in later Gaulish there was a tendency for

final -s and -n to be dropped. However, French toponyms suggest that stress could be variably

placed; there are numerous examples in which two different French toponyms are descended

from a single, but variably stressed, Gaulish ancestor, for example, Nemours from Nem´ausus,

but Nˆımes from N´emausus. Falc’hun (1981:294–313) has suggested that penultimate stress

was more archaic and that antepenultimate stress was an innovation which spread from the

Mediterranean. The placement of stress in Gaulish has also been discussed recently by De

Bernardo Stempel (1994; 1995) and Schrijver (1995:20–21).

continental celtic

173

4. MORPHOLOGY

4.1 Word formation

Like other ancient languages of the Indo-European family, the Continental Celtic languages

are fusional. Words are composed of a basic morpheme to which derivational prefixes and

suffixes may be affixed. There is some evidence that multiple prefixation, as is common in

the Insular Celtic languages, was productive. A stem-vowel could be added to the end of this

complex, after which the inflectional ending, if any, was attached.

4.2 Nominal morphology

Nominals, which include nouns, adjectives, and pronouns, are inflected for case, gender,

and number. There is evidence for all eight classical Indo-European cases – nominative,

accusative, genitive, dative, locative, instrumental, ablative, and vocative – but not in all

numbers and declensions, and not in all languages. The familiar three genders – masculine,

feminine, and neuter – of the Indo-European family are well documented, as are the singular

and plural numbers. There is some slight evidence that the dual also existed.

4.2.1 Nominal stem-classes

4.2.1.1 Hispano-Celtic

The nominal inflection of Hispano-Celtic as presentlyattestedis givenin Table 8.3. Uncertain

identifications are followed by a question mark.

The o-stem genitive singular in -o is an innovation via a proportional analogy with the

pronominal paradigm. Compare the Proto-Celtic ¯a-stem genitive singular syntagm

∗

sosy¯as

bn¯as “this woman” with o-stem

∗

sosyo wir¯ı “this man”. In order to extrapolate the nominal

Table 8.3 Hispano-Celtic nominal inflection

¯a-stem o-stem i-stem u-stem n-stem

1

n-stem

2

r-stem nt-stem C-stem

Singular

Nom. -a -o

´

s-i

´

s-u-i -

´

s

Acc. -am -om -im -nTam

Nom.-acc. neut. -om

Gen. -a

´

s-o -e

´

s? -uno

´

s -ino

´

s-e

´

ro

´

s -nTo

´

s-o

´

s

Dat. -ai -ui -e/-ei? -uei -unei -inei -ei

Loc. -ei

Instr. -u? -unu?

Abl. -as -us -is -ues? -unes -es

Plural

Nom. -a

´

s? -oi? -i

´

s-e

´

re

´

s-e

´

s

Acc. -a

´

s-u

´

s? -u

´

s?

Nom.-acc. neut. -a

Gen. -aum -um

Dat. -o/uPo

´

s

174 The Ancient Languages of Europe

Table 8.4 Lepontic nominal inflection

¯a-stem o-stem i-stem n-stem C-stem

Singular

Nom. -a -os -is -u

Acc. -am -om

Nom.-acc. neut. -om

Gen. -oiso, -i

Dat. -ai -ui -ei? -onei/-oni

Plural

Nom. -oi -ones

Acc. -e

´

s

Dat. -oPos -onePos

genitive singular in -o one need only notice that in the ¯a-stem inflection the pronominal

and nominal endings are identical after the -y- in the demonstrative (see Prosdocimi 1991:

158–159; Eska 1995:41–42). The identification of o- and n-stem forms in -u as instrumental

singulars has been proposed by Villar (1993–1995). The o-stem nominative plural in -oi is

perhaps attested once (or twice) in a single inscription. A single accusative plural form in -u´s

could be either an o- or u-stem. In the animate n

1

-stems, the lengthened-grade suffix

∗

-¯o(n)-,

proper only to the nominative singular, has been extended throughout the paradigm.

4.2.1.2 Lepontic

The nominal inflection of Lepontic as attested is given in Table 8.4. Uncertain identifications

are followed by a question mark.

The o-stem genitive singular in -oiso is attested only in very early forms. It ap-

pears to continue Indo-European pronominal

∗

-osyo; Colonna (in Gambari and Colonna

1986:138) and Lejeune (1989:64) treat the Lepontic ending, which is also attested

once in Venetic (see Ch. 34, §4.1.1 [7]) (but see now Eska and Wallace 1999), as a

metathesized variant. Eska (1995:42) suggests that it is the result of a crossing with

the Lepontic descendant of the Proto-Indo-European pronominal genitive plural

∗

-ois¯om

(cf. Hisp.-Celt. ´soi´sum). De Hoz (1990) suggests that, in addition to earlier -oiso and

later-¯ı, Lepontic also had an o-stem genitive singular in -¯u from ablative singular

∗

-¯od. These forms have traditionally been interpreted as animate n-stem nominative singu-

lars (see Eska 1995, especially pp. 34–37 for a critique of de Hoz’s proposal). Attested once,

the n-stem dative singular -oni seems to represent an early instance of the locative in dative

function (see now Eska and Wallace 2001). The consonant-stem accusative plural ending -e´s

(attested once) presumably has been remade by analogy with the vocalism of the nomina-

tive plural ending, since inherited

∗

-ˆs would have yielded Proto-Celtic

∗

-ans >

∗

-¯as.The

spelling of the sibilant with <

´

s> perhaps indicates that an epenthetic

∗

-t- was inserted into

the inherited

∗

-ns group (perhaps

∗

-ens >

∗

-ents ><-

´

es> = /-

˜

ets/), as is attested elsewhere

in the accusative plural ending of Luwian (so also in Cis. Gaul. acc. pl. arTua´s).

4.2.1.3 Gaulish

The nominal inflection of Gaulish as attested is given in Table 8.5. Multiple exponents of a

single ending are given in chronological order of attestation. The inflectional morphemes

continental celtic

175

Table 8.5 Gaulish nominal inflection

¯a-stem o-stem i-stem u-stem n-stem r-stem C-stem

Singular

Nom. -a -os, -o -is -us -u -ir -s

Acc. -an,-em -om, -on -in -erem

-en, -im

Nom.-acc. neut. -on -e? -u -an

Gen. -as, -ias -i -ios? -os

Dat. -ai, -i -ui, -u -e -ou -i

Loc. -e

Instr. -ia -u

Vo c.-a-e

Dual

Nom.-acc. -o

Plural

Nom. -as -oi, -i -is -oues -es

Acc. -as -os, -us

Nom.-acc. neut. -a

Gen. -anom -on -iom -ron

Dat. -abo, -abi? -obo, -obe? -rebo, -rebe? -bi

Instr. -abi? -obe? -rebe?

attested only in north Etruscan or Greek characters are here transcribed into Roman

characters. Uncertain identifications are followed by a question mark.

The ¯a-stem inflection in later Gaulish has been deeply affected by the inherited ¯ı-stem

inflection. Accusative singular forms with e-vocalism in the ¯a- and r-stems appear to be

the result of the raising of /a/ before the final nasal, as is also indicated for Old Irish. The

final -m of ¯a-stem accusative singular -em is usually taken to be archaic. The ¯a-stem dative

singular in -¯ı is the result of contraction of -ai <

∗

-¯ai.The¯a-stem genitive plural in -anom

is attested in only one inscription and could, therefore, represent a local innovation. Owing

to the difficulty of interpreting the documents, it is unclear whether ¯a-, o-, and r-stem

forms in -bi, -be are dative or instrumental plural. The o-stem dative singular in -¯u could

represent either the apocope of -i from earlier -¯ui or syncretism of the dative, instrumental

(and ablative?) singular. The neuter nominative-accusative singular n-stem in -an regularly

continues

∗

-˜. The consonant-stem dative singular in -i continues the inherited locative

singular ending.

4.2.2 Pronouns

Partial paradigms of a variety of pronominals are attested in Continental Celtic. The demon-

strative stem

∗

so/¯a- is attested in Hispano-Celtic and Gaulish, with the initial

∗

s-, originally

only in the masculine and feminine nominative singular, extended throughout the paradigm.

It seems to have been fully stressed in Hispano-Celtic; it is unclear whether it everwas stressed

in Gaulish. Gaulish also had a reduplicated formation attested in nominative-accusative

neuter singular sosin and sosio. This -sin element also seems to be found in several forms

176 The Ancient Languages of Europe

which appear to be ancestors of the Insular Celtic article, namely, in=sinde, indas (with

early loss of initial s-; the sign = represents a clitic boundary), and o=’nda (contracted in

composition with a preposition).

The relative pronominal stem

∗

yo- appears as a stressed and inflected form in Hispano-

Celtic. In Gaulish, it has been reduced to an uninflected subordinating clitic particle =yo.

The anaphoric pronominal stem

∗

ei- appears to continue its inherited function in two

Gaulish forms, namely, eianom and eiabi. It also can function as a clitic object pronoun.

Many scholars believe that the nominative can also be attached as a clitic to a verb for

emphasis, for example, neuter singular buet=id, though some would segment the sequence

otherwise.

Seemingly related to the anaphoric stem is a series of forms which may ultimately be

related to the Latin pronoun iste. These are Hisp.-Celt. i´sTe and ´sTa ´m and ´sTena (with

aphaeresis?), Lep. i´sos, and Gaul. ison and isoc (with attached deitic

∗

=

ke?).

Hispano-Celticalso has a pronominal stem o- attested in the the forms osia´s (fem. gen. sg.?)

and osa´s (fem. acc. pl.?) which perhaps displaysa differentablaut grade of the anaphoric stem.

There are very few personal pronouns attested. The only ones which have been securely

identified are the clitic accusatives, Gaulish first singular =me,firstplural=snj and first

singular dative=mi <

∗

mo„. The attestedpossessive pronounsarefirst singular imon and mon

and second singular to. It also seems probable that the first singular nominative form =mi

(< acc.

∗

m¯e) and second singular = tu are attested as emphasizing pronouns, though they

have been otherwise interpreted (see §4.3.6).

Finally, the deictic stem

∗

kei- is attested in the Gaulish syntagm du=ci, literally “to here,”

employed as a connective “and.”

4.3 Verbal morphology

In typical Indo-European fashion, the Continental Celtic verb is marked for tense, voice,

and mood.

4.3.1 Tense

In the verbal system, there is good evidence for the present, preterite, and future tenses; Meid

(1994:392–393) suggests that Hispano-Celtic also continued the Indo-European imperfect,

but this is uncertain. The present tense is attested in a number of common Indo-European

formations.

The preterite is composed of forms which continue Indo-European perfects, s-aorists,

and renewed imperfects. There is also at least one example of suppletion (see Schmidt 1986

and Eska 1990). Owing to phonological reductions, the Continental Celtic s-preterite has in

some cases been augmented with a thematic (i.e., o-stem) ending; compare unaugmented

Gaul. 3rd sg. prinas “he sold” <

∗

k

w

ri-n-h

2

-s-t (which would have been homophonous with

the second singular), and augmented Gaul. 3rd sg. legasit “he placed” <

∗

leg

h

-eh

2

-s-t +

∗

-et.

The Continental Celtic t-preterite is of multiple origin. Like the Insular Celtic t-preterite,

it continues the Indo-European s-aorist in certain forms: for example, Gaul. 3rd sg. t

.

oberte

<

∗

to-b

h

er-s-t + 3rd sg. perf. -e, which was affixed to characterize the form as third sin-

gular overtly once the -t was regrammaticalized as the exponent of tense. A perfect ending

was also affixed to inherited imperfect forms in order to recharacterize them as preterites:

for example, Lep. 3rd sg. KariTe “he placed” <

∗

k-r

-ye-t + -e after the apocope of pri-

mary

∗

-i (at least after voiceless consonants) caused the present and imperfect to fall

together.