West B.A., Murphy F.T. A Brief History of Australia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

10

Australia’s large migrant population, where 24 percent of the current

population was born overseas and another 26 percent had at least one

parent born overseas, means that at least 200 languages and dialects

are spoken in the country’s 8.1 million households. While English is

the national language, 16 percent of the population speaks another

language at home, with Italian, Greek, Arabic, Cantonese, Mandarin,

and Vietnamese the most common (Australian Bureau of Statistics

2008, “Country of Birth”).

This great diversity of people lends great religious diversity to

the country as well, with 6 percent of the population adhering to a

wide variety of non-Christian faiths, including Islam, Buddhism, and

Judaism, and another 31 percent professing no faith at all. Of the

Christian faiths, the largest percentage are Roman Catholic, at 26 per-

cent; followed by Anglican, 19 percent; and others such as Greek and

Russian Orthodox, Uniting, and Baptist, 19 percent (Australian Bureau

of Statistics 2006, “Religious Affiliation”).

Since the landing of the First Fleet in 1788, Australia has been a

predominantly urban society. As the food historian Michael Symons

notes, “this is the only continent which has not supported an agrarian

society” (1982, 10); Aboriginal hunting and gathering quickly gave

way to processed and preserved imports. Rather than small, family-

run farms on which a majority of people lived and worked, from the

beginning white Australia supported a small number of large, indus-

trial-scale sheep and cattle stations while the majority of people lived

in and around the continent’s coastal cities and towns. Today about

88 percent of the Australian population lives in urban areas, with 64

percent living in the capital cities alone, which is double the rate of the

United States (Clancy 2009). For the historian Geoffrey Blainey, this

strong centralization is the result of Australia’s “tyranny of distance”:

The vast distances and high cost of transport within the country have

made decentralized settlements unviable from the earliest days of white

settlement (1966). In addition, the arid nature of most of the conti-

nent and the extreme heat and humidity in the far north have made

large-scale settlement in these regions next to impossible. As a result,

85 percent of the continent’s population lives in what Blainey calls the

Boomerang Coast, a stretch of land from Adelaide in the south through

Brisbane in the north and including Melbourne, Sydney, Hobart, and

Canberra (Nicholson 1998, 52–53). Altogether, this territory makes up

less than a quarter of the country’s landmass.

In addition to their centralized settlement pattern, Australians enjoy

one of the highest qualities of life on Earth; in 2009 Australia ranked

11

DIVERSITY—LAND AND PEOPLE

second on the United Nations’s Human Development Index (HDI)

behind Norway (United Nations Development Program [UNDP]).

Rather than looking strictly at gross domestic product (GDP) or other

economic factors, the HDI combines income purchasing power (pur-

chasing power parity, or PPP), life expectancy, and educational attain-

ment (United Nations Development Program 2008, 7). Australia ranks

just 22nd in the world on the income measurement, at U.S.$34,923 per

person, but first in educational attainment and fifth in life expectancy,

at 81.4 years (UNDP). In comparison, the United States is 13th on the

HDI overall: ninth in purchasing power, 21st in educational attainment,

and 26th in life expectancy at 79.1 years (UNDP 2). Additionally, the

Economist magazine ranks Melbourne, Australia’s second-largest city,

as the world’s second most livable city after Vancouver, Canada, while

Perth, Adelaide, and Sydney, the capitals of Western Australia, South

Australia, and New South Wales, respectively, also make the top 10 at

fourth, seventh, and ninth (Economist Intelligence Unit 2008).

Despite the relative livability of Australia, the country’s population

does not share equally in the benefits of good health and well-being,

high educational attainment, or income distribution, setting it apart

from the other countries with very high HDI rankings. For example,

in terms of income inequality, Australia resembles the United States, at

13th on the HDI, far more than it does Norway. In Australia the low-

est 10 percent of income earners make just 45 percent of the national

median, while the highest 10 percent make 195 percent of the median;

the comparable figures for the United States are 38 percent and 214

percent, and for Norway 55 percent and 157 percent (Smeeding 2002,

6). In other words, Norway’s richest and poorest people are more like

each other in terms of purchasing power than those in Australia or the

United States.

While poverty, lack of education, and poor health care can be found

in small pockets throughout the Australian population, on average the

least-well-off group are the approximately 2 percent who identify as

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, who together make up the country’s

Indigenous people. As a result of harsh and discriminatory laws that

have impeded self-determination for more than 200 years, this popula-

tion in 2001 had a life expectancy that on average was 18 years less

than that of other Australians, a household income rate only 62 per-

cent that of non-Indigenous Australians, an unemployment rate more

than three times the national average, and much lower educational

attainments (Australian Human Rights Commission 2006). Another

repercussion of generations of repression and this vast inequality is that

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

12

Indigenous people, while constituting a tiny proportion of the general

population in Australia, made up 22 percent of the prison population

in 2005; some 6 percent of the Indigenous male population between

25 and 29 were imprisoned, compared to only 0.6 percent of men that

age overall (Australian Human Rights Commission 2006). While some

efforts have been made at both the federal and the state/territory lev-

els to deal with this inequality, far more needs to be done to right the

wrongs of the past 220 years.

Like its land and people, Australia’s history is one of diversity and

great contrasts. On the one hand, Australia is home to the oldest sur-

viving culture on Earth, where for between 45,000 and 60,000 years

countless thousands of generations lived and died but left relatively

few markers behind through which we can understand their long his-

tory. On the other hand, Australia’s non-Indigenous population can

be dated back only as far as 1788, 168 years after the landing of the

Mayflower pilgrims in the United States and 224 years after French

Huguenots landed in Florida. In the approximately 220 years between

1788 and the present, non-Indigenous Australians have transformed

their culture and territory so thoroughly that very little of the original

remains. It is with this process of transformation that this book is pri-

marily concerned.

13

2

aboriginaL history

(60,000 bp–1605 c.e.)

a

boriginal history from 60,000 years ago until Australia was first

sighted by Europeans in 1606 is as complex and varied as the

history of any other group of people on Earth. Saying that today’s popu-

lation of Aboriginal Australians are members of the oldest surviving

culture in the world by many tens of thousands of years is not synony-

mous with saying that their culture has not changed during this very

long period of time, or even that it had not changed prior to the arrival

of Europeans in the early 17th century. Tremendous ecological changes,

from the rise of global sea levels that separated Tasmania, New Guinea,

and Australia’s mainland, to the loss of the continent’s megafauna, cer-

tainly contributed to great changes in people’s social and material lives.

Other changes in social structures, social systems, languages, and tech-

nological know-how are also sure to have taken place over the course

of this span of 60,000 years. Migration, warfare, floods, drought, animal

and plant extinctions, overseas trade, and a vast array of other factors

were also at play in the lives of the millions of individuals who lived

and died on the continent before the arrival of the Dutch.

Despite this certain diversity and change, the historical record

for these populations remains fairly sparse for a number of reasons.

First, at no point in their precolonial history did Australia’s Aboriginal

populations develop writing, and so they left no record of events.

Second, ecological change has placed the earliest archaeological sites

on the continent under water. Third, our science is not yet able to

verify with 100 percent reliability the dates of organic materials from

as far back as the earliest migrations. Finally, vastly different views of

the nature of existence between Aboriginal and other peoples mean

that Aboriginal oral histories have often been misunderstood when

told to outsiders.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

14

Jinmium

15

ABORIGINAL HISTORY

As a result of this confluence of factors, most Aboriginal history has

to be patched together from a very incomplete archaeological record,

linguistic evidence from our contemporary knowledge of Aboriginal

languages, genetic comparisons between contemporary peoples who

may have descended from common ancestors, oral histories and other

stories gathered at the time of the first interactions between Aboriginal

and non-Aboriginal peoples, and ethnographic information gathered

over the past 400 years of interaction. Of course, a certain degree of

conjecture based on these various sources of information is also inher-

ent in this kind of salvage history writing but will be kept here to

only the most viable hypotheses based on the hard evidence currently

available.

Ancient Prehistory: 60,000–22,000 BP

Since the arrival of the first Aboriginal people about 60,000 years ago,

the Australian continent has undergone tremendous change. When

they arrived, present-day Australia, Tasmania, the Torres Strait Islands,

and the island of New Guinea were all connected. These lands formed

the continent of Sahul, a landmass approximately the size of contem-

porary Europe west of the Ural Mountains. The continent contained a

large number of unique plant and animal species due to its long period

of isolation (about 38 million years) from other landmasses, including

an estimated 13 species of so-called megafauna. These were very large

versions of contemporary kangaroos, wombats, and other marsupials;

many other species of megafauna had died out prior to the continent’s

inhabitation by humans. The climate was generally cooler and drier

than the region is today, with periglacial and even glacial regions in

the Highlands of New Guinea and the Dividing Ranges of southeast-

ern Australia. Nonetheless, Sahul 60,000 years ago encompassed the

same wide variety of ecological niches as today’s separate landmasses.

Tropical forests covered the northern lowlands, while temperate for-

ests existed in the south and highlands of the north. The center of the

continent contained both deserts and savannahs, as it does today. Some

pollen studies appear to show that even the continent’s dry center con-

tained some forest land, but this hypothesis has not been accepted by

all archaeologists or other scientists working in this area.

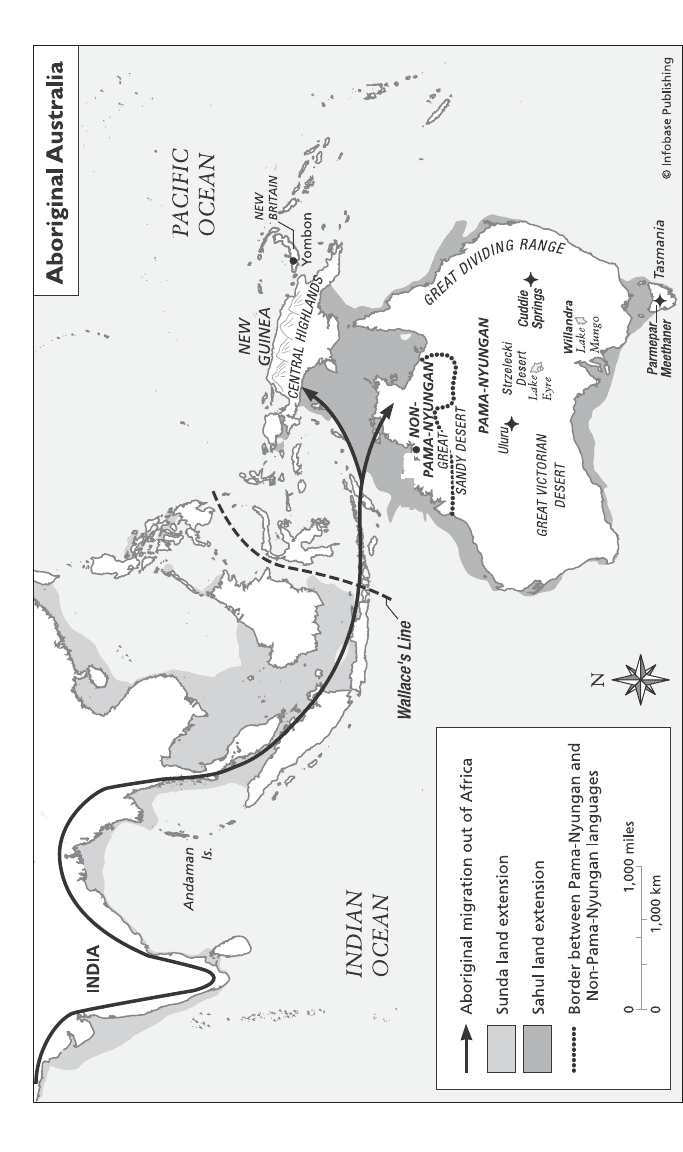

Even though there is no absolute certainty about the direction from

which the ancient migrating population arrived on Sahul, the most via-

ble hypothesis is that after spending thousands of years leaving Africa,

passing through the Middle East and India, and heading south through

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

16

mainland Southeast Asia, which was then much larger than today, a

small group of migrants sailed across about 35 miles of open sea to

land somewhere in Sahul’s far north, or contemporary New Guinea.

Other hypotheses, such as migration direct from India or even the in

situ evolution of humanity in Sahul, have been disproven in recent

decades with the development of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid

(mtDNA) analysis.

Like the migration route, the period of initial migration is also a

highly contested feature of Aboriginal Australian history that involves

archaeologists, physical anthropologists, geneticists, linguists, bota-

nists, and a host of other scientists. Most Aboriginal people themselves

find this debate irrelevant or even insulting, for it discounts their own

origin myths, which are timeless. Nonetheless, until the 1960s, most

scientists believed the original period of migration was as recent as

about 10,000–12,000 years ago, or about the same time as the colo-

nization of the Americas from northern Asia. With the development

of advanced carbon 14 dating techniques, this date was pushed out

toward 40,000 years before the present (BP) by the middle of the

1980s. And with the development of thermoluminescence dating in

the 1990s, 60,000 years BP has become a common estimate. Genetic

testing of mitochondrial DNA, which looks at female lineages of cer-

tain genes and determines age through the evaluation of gene muta-

tions, has also provided dates of around 60,000 years BP for the initial

peopling of the continent.

Nonetheless, contradictory evidence from other disciplines has

compelled scientists to continue exploring this intriguing subject. For

example, pollen studies that show an increase in the existence of fire

on the continent, which may indicate human use of fire to clear terri-

tory and make hunting easier, have indicated that it is remotely possible

that humans were using fire in Australia as far back as 185,000 years

ago. The use of TL on materials found in Jinmium, Western Australia,

has likewise produced a date as far back as 176,000 years, though this

has since been forcefully rebutted by others. On the other side of the

debate, archaeologists have found very few sites in Sahul that can be

verified as having existed more than 40,000 years ago. In their review of

all the evidence that had been retested using thermoluminescence and

other techniques, O’Connell and Allen (2004) conclude that even with

these new technologies, 45,000 BP is the earliest date for which we can

be certain of human inhabitation of Sahul. Nevertheless, because their

conclusions do not take genetic evidence into account, many consider

this a conservative date.

17

ABORIGINAL HISTORY

Another problem with our understanding of the initial peopling of

Sahul is whether one migrant population settled and spread slowly to all

corners of the continent, from the Highlands of New Guinea to the south-

ern tip of Tasmania, or whether there was a continual flow of migrants

over many thousands of years. Discrepancies in the archaeological record,

such as the fact that the oldest archaeological sites have been found in

Australia’s southeastern states of New South Wales and Tasmania rather

than northern regions, and the odd division of Australian languages into

C14 and

LuMinesCenCe dating

r

adiocarbon dating refers to the process of measuring the

amount of the radioisotope carbon 14, or C14 (carbon atoms

with eight neutrons rather than the usual six) in an organism after

it dies. All living things sustain an amount of C14 in balance with the

amount present in the atmosphere. This amount remains constant in

the organism until the moment of death, at which time the C14 begins

to decay at a half-life rate of 5,730 years. C14 has approximately 10

half-lives, or 57,000 years, the furthest back radiocarbon dating can

go. The dating process compares the amount of C14 in the atmo-

sphere to that remaining in the organism, thus providing its time of

death. Organisms suitable for such dating are animal or human bone,

charcoal, peat, marine shell, and antlers or parts thereof.

In the 1960s scientists working on the problem of dating non-

carbon-bearing samples developed several methods of luminescence

dating, the most common of these being thermoluminescence, or TL.

This method can date inorganic material containing crystalline miner-

als that when either heated, as with pottery, or exposed to sunlight,

as with sediments, accumulate radiation. Subsequent reheating of the

material at temperatures of 842°F (450°C) or greater releases this

energy in the form of light, the thermoluminescence. This creates a

blank slate or “time-zero” for the material to accumulate new energy

over time. The amount of light released in the heating process is

correlated with the amount of radiation stored within the material.

Measurement of this light provides the date of last firing or exposure

to sunlight. While thermoluminescence has an age range that is often

far greater than that of C14 dating, it is used in conjunction with a

variety of other methods of dating and biological processes for greater

accuracy.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

18

two groupings, Pama-Nyungan and non-Pama-Nyungan, have convinced

many scholars over the years that Australia was populated by several

waves of people from India as well as Southeast Asia. In addition, simula-

tion studies, which use computer modeling in the creation of hypotheses,

have posited that there have to have been multiple migratory groups to

Sahul to prevent incest and sex imbalances.

What these simulation studies do not tell us, however, is whether or

not these multiple migrations took place over several years, decades,

centuries, or even millennia. As a result of recent studies, physical

anthropologists and geneticists working in the area of mtDNA believe

they have answered this long-standing question in favor of the short-

est possible time lag between migrations. Their data show with relative

certainty that Australia, New Guinea, and all of Melanesia were popu-

lated by a single group of migrants who left Africa 70,000 years ago at

the earliest and populated their current home about 58,000 years ago,

plus or minus 8,000 years (Hudjashova et al. 2007). This same evi-

dence also points to a long period of relative isolation after this initial

migration, whereby even prior to the submergence of the land bridge

linking Australia and New Guinea, the populations of these two regions

remained largely separate. The only exception to this trend evidenced

by the genetic material tested so far is an influx of New Guineans into

northern Australia about 30,000 years ago.

The history of this population remains fairly vague after they began

settling Sahul. We do not know whether communities fought wars

against each other or were so spread out on the vast continent as to be

able to live peaceably. We do not know how soon their proto-Australian

language or languages began dividing into the vast number of Australian

and Papuan languages evident by the time of European contact in the

17th century. We do not know whether the Dreaming stories and their

accompanying rituals, which make up the backbone of Aboriginal reli-

gion even today, were imported with them, were developed during the

period of migration, or were begun after settlement on the continent.

The list of unanswered and probably unanswerable questions about this

most ancient of populations is very long.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the somewhat sparse archaeological

record of about 100 sites identified to be older than 22,000 years, the

period of the last glacial maximal (LGM) and a period of dramatic change

on the continent, we do have a very good idea about a few aspects of life

on prehistoric Sahul. Archaeologists working at sites as far removed as

Lake Mungo’s Willandra area in western New South Wales, Parmepar

Meethaner in Tasmania, and Yombon on New Britain, New Guinea,

19

ABORIGINAL HISTORY

have found remains dating from before 22,000 BP. While some aspects

of these ancient populations’ tool kits and subsistence regimes were

similar, others differed. For example, people in all three regions lived

on a food collectors’ diet consisting largely of fish, shellfish, and small

mammals. Of course local fruits, roots, greens, mushrooms, and other

gathered foods would also have made up a substantial portion of their

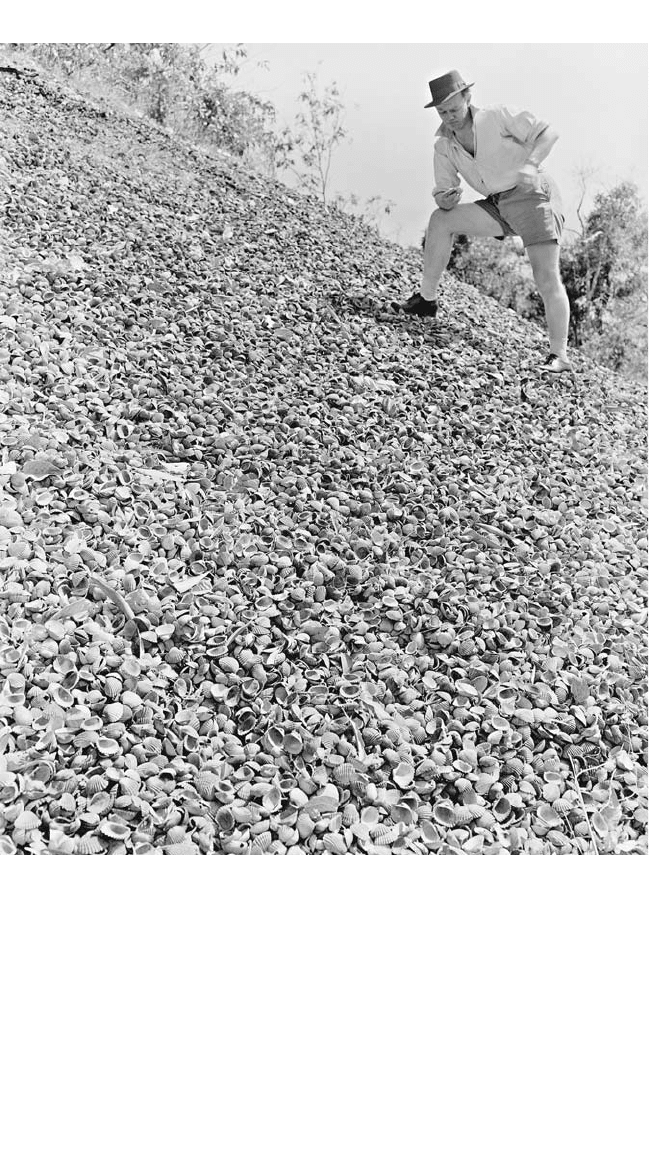

Midden of mollusk shells and crustaceans near Weipa, on the northwest coast of the Cape

York Peninsula, Queensland

(National Archives of Australia: A1200, L26732)