Water Power and Dam Construction. Issue November 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM NOVEMBER 2010 11

WORLD COMMISSION ON DAMS - 10 YEARS ON

“Perhaps an indication of the WCD’s success was that no one

interest was completely happy with the nal product,” former WCD

commissioner Deborah Moore comments. “This means that it truly

represented compromises amongst all interests. My hope had been

that the report would have engendered fruitful, participatory dialogue

at the national and local level that would have inuenced national

laws and policies. That did not happen as much as I would have

liked. However, the WCD report has become the de facto interna-

tional benchmark for dams against which all other policy proposals

are compared, even if the guidelines and recommendations were not

ofcially adopted.”

TEN YEARS LATER

Former secretary general Steiner said that although some had hoped

for a summary judgement or an end to the dams conict, the WCD

recognised that there was no magic formula. “Ten years is not much

time to transform water and energy governance, and it is clear the

issues which led to the establishment of the commission in 1998 are

still current,” he says. “In addition new issues such as climate change

have emerged to drive the demand for renewable energy. The debate

on large water infrastructure continues.”[3]

Bosshard, from an International Rivers’ perspective, agrees:

“The sensitivity of the environmental impacts of dams has grown.

This year’s Global Biodiversity Outlook and IUCN’s Red List of

Endangered Species have found that we continue to lose biodiversity

at an alarming rate, and most particularly in freshwater ecosystems.

Dams are one of the main factors of this trend,” he claims, “and their

social and environmental problems have clearly not been resolved.”

Deborah Moore is amazed that the world is still discussing the

WCD report ten years later. “This shows the report has not simply

stood on the shelf gathering dust. It is a living document – it has been

translated, disseminated and debated. The ideas are still clearly rel-

evant – because the conicts and controversies remain and because

the damage caused by dams continues to grow,” she says. “Until we

can ensure that dam-affected communities are project beneciaries,

and until we can ensure that aquatic ecosystems can be protected, the

WCD recommendations will remain relevant.”

To monitor WCD’s inuence on dam construction and operations

ten years on, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

carried out a small snapshot survey of the global uptake, impact and

perspectives on the commission’s recommendations. The web-based

survey ran for 11 weeks until the end of July 2010.

The survey attracted responses from a wide range of countries and

categories of stakeholders. The main conclusions indicated extensive

knowledge of the WCD recommendations and widespread uptake of

its principles in one form or another. However, there were signicant

weaknesses in implementation. The strategic priorities which received

the most attention were gaining public acceptance, recognising enti-

tlements and sharing benets, with comprehensive options a close

third. While some respondents believed that little attention appears

to have been made to addressing existing dams, with few signicant

changes in practice. [2]

According to Peter Bosshard, awareness about the social impacts

of dams and the rights of affected people has grown over the past ten

years. “Yet we continue to see big gaps between rhetorical commit-

ments and the realities on the ground in many countries,” he adds.

“International development challenges are constantly evolving.

Nobody expects the WCD framework to be implemented to the letter

ten years after it was published. Yet the changing global environment

has conrmed the relevance of the WCD’s key recommendations.”

Moore has seen developments taking place. “One of the most

promising developments of the past decade,” she says, “is the fur-

ther demonstration that true partnership amongst key stakehold-

ers can produce transformative results. Successes on the ground

include Guatemala, the Klamath basin in the US, the Pangani river

in Tanzania and others. These demonstrate that many of the WCD

recommendations around negotiated stakeholder agreements are

working in practice to foster resource-sharing agreements amongst

the affected stakeholders.” [4]

“Stakeholder involvement nowadays is widely considered an

essential step in the decision making on dam development,” Palmieri

comments. “This is certainly the case for multilateral development

institutions and most bilateral ones. The private sector has also

advanced this practice a lot. The next challenge is to make the process

both inclusive and efcient, ie reaching decisions in a time compat-

ible and relevant to the needs to be addressed. This is what I call the

critical speed concept.”

Palmieri reiterated the point that dams not adequately planned,

built and operated can cause unnecessary impacts, but the opposite

is also true when the process is well done. “I believe practice has

improved,” he said and gave the example of the Worldwide Wildlife

Fund which has been working with the International Hydropower

Association (IHA) on a campaign on dams. “They have progressively

and constructively worked with industry and other stakeholders to

produce guidelines for good decision making processes,” he adds.

“The WCD prompted a constructive dialogue which in turn led to the

development of progressive guidelines by the hydro industry; I should

venture to say that this is part of what WCD was trying to achieve.”

Moore still has her doubts. “Practices remain all over the map, in

terms of effectiveness and accountability. There are isolated instances

of policies being followed and improvements being made, and there

Ten years from now

IWP&DC asked a few industry members what they would like to see happening

in the dams debate ten years from now?

Kader Asmal, former chair of WCD:

A fresh view should be provided: one that is non-antagonistic.

Peter Bosshard, Policy Director, International Rivers, US:

Traditional and new dam builders should benet from the experience of the

WCD framework and adopt its key principles as they prepare and strengthen

their own environmental policies. We also believe that government agencies,

funders, the dam industry and NGOs would benet from renewed dialogue

processes at the national and international level.

Thomas Chiramba, Head of Freshwater Ecosysetms Unit, United Nations

Environment Programme:

UNEP would recommend that there be established a non-partisan forum that

can engage both the old and new players in a multi-stakeholder dialogue about

dams, and generate the political will needed to transform the provision of

water and energy services.

Deborah Moore, former WCD commissioner, Executive Director Green

Schools Initiative, US:

1) Move the dams debate ‘upstream’ in the options assessment process to reduce

conict over dams that have made it out of the planning process. All stakeholders

need to be involved in the planning and evaluation process much earlier.

2) Focus on non-dam alternatives...with fewer costs and negative impacts.

3) Improve the performance of the world’s existing large dams to squeeze out

all the economic benets from the investments already made

Alessandro Palmieri, Lead Dam Specialist at the World Bank:

1) More efforts should be made to listen to local stakeholders and promote

local development, in addition to national development.

2) Build capacity in national consultants, planners and contractors, so that

they become the real owners of the projects they need (the IHA Sustainability

Protocol can be a very useful tool in that regard).

3) Address environmental aspects with priority on the main issues and with

larger use of adaptive management. Include payment items, in construction

contracts, for the implementation of the key provisions of environmental

management plans.

4) The allocation of carbon funds to be used, during project operation, to

address unforeseen negative impacts (both environmental and social).

Thayer Scudder, former WCD commissioner, Professor of Anthropology,

California Institute of Technology, US:

Under environmental risks we must think about two kinds in particular. One concerns

the global ecological implications of further reducing the number of free-owing rivers.

The other concerns the nancial and development risks associated with the likely

extreme drought, rainfall and storm risks expected as a result of global warming.

12 NOVEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

WORLD COMMISSION ON DAMS - 10 YEARS ON

are examples of some creative solutions arising. Yet in the last ten

years there has been a resurgence of dam building and many more

communities and rivers are at risk.”

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

ICOLD prides itself over its 82-year history as being able to evolve

with the requirements of mankind. It is condent that this will con-

tinue. Respecting the past, facing reality and looking to the future are

to be this commission’s guiding principles to carry it forwards.

“Negative impacts should never be suppressed, overlooked or

underestimated, when promoting future development,” ICOLD pres-

ident Jia Jingsheng told IWP&DC. “One should remember that all

members of society have the right to benet from a project. Attention

to the social and environmental aspects of dams and reservoirs must

be a priority, at the forefront of our activities, in the same way as

concern for safety is invariably a top priority. The construction and

operation of a dam and reservoir can no longer be considered as a

purely scientic and technical matter.”

Former WCD commissioner Jose Goldemberg believes that the

WCD report has had a healthy impact on dam building and licens-

ing practices. Some dams are very good and create few problems

he said, giving Xingo in Brazil as one such example. Furthermore,

Goldemberg also believes that stakeholder involvement has improved.

“But not to the point desired by the NGOs in the WCD,” he says.

“They were aiming at the consent of all stakeholders. The truth is that

the balance between the interest of the ones that are hurt by dams (as

well as unavoidable environmental damage), and the hundreds of

thousands (or millions) that are benetted thousands of kilometres

away, has to be sought. Elected governments have to make these deci-

sions considering a variety of factors.”

It is all a question of balance. John Briscoe describes this well.

“While those concerned with single issues (the environment) and

single groups (affected people) have merged into a powerful anti-

dam lobby, those who have the responsibility for the well-being of

all citizens in a developing country have a different more complex

task. They have to look not only at all individual groups or particular

issues, but make trade-offs and consider the relative weight of assets

and liabilities.” [1]

Perhaps what speaks volumes is the fact that the WCD guidelines

were not accepted by a single country which builds dams. The atten-

tion gradually shifted to the non-controversial strategic priorities

instead. “The WCD strategic priorities hold rmly and should con-

tinue to guide dam development,” Palmieri states. “However the 26

guidelines, which the commissioners never considered to be compli-

ance elements, remain controversial and largely unused. Insisting on

such guidelines has done a lot of damage to the WCD report at an

international level.”

As Briscoe points out, infrastructure has now returned to centre

stage for most development agencies. The proportion of World Bank

lending to infrastructure rose from 20% in 2000 to 40% by 2008.

Investment in water infrastructure also increased by US$4.4B from

FY03-FY09. “What has changed,” Briscoe adds, “is the belief that

major water infrastructure, with reasonable attention to social and

environmental issues, is vital for developing countries and is some-

thing that the Bank must support.” [1]

The situation has improved in relation to better practices, compli-

ance and accountability, Goldemberg says: “And this is the reason

why World Bank involvement in nancing dams has increased.”

Meanwhile, in the UNEP survey carried out in July this year, only

18% gave positive views on the nancing of dams. Fifty-seven percent

of respondents believed that nancial institutions and the nancial

sector had not taken up the WCD recommendations in any meaningful

way. Furthermore, the report concludes that many stakeholders con-

tinue to experience a ‘business as usual’ scenario on the ground. [2].

BUSINESS AS USUAL

“Business as usual – and the continued in-ghting over dams – is

neither a feasible nor desirable option,” Moore says. “Ten years on

there is evidence of both failures and successes in the dams sector.

There are no shortcuts to equitable and sustainable development, it’s

hard work.”

So what is the way forward? Improvements are being made in dif-

ferent areas but not always to the complete satisfaction of all involved

parties. “The question is not adopt the WCD report or reject it,”

Moore continues. “The question is: what are the ideas, criteria and

principles from the WCD report that still make sense to implement

as we move forward?” [5]

Alessandro Palmieri from the World Bank gives the example of

the Dams and Development Project (DDP) which came to an end in

2007. The compendium Dams and Development: Relevant Practices

for Improved Decision Making represents the DDP’s main output.

Former WCD secretary general Achim Steiner stated that instead of

focusing on shortcoming and failures, this publication ‘presents prac-

tices that, though not exempt from weaknesses, show a positive and

progressive way of doing things’.

Palmieri nds that this is a remarkable statement which departs

from the sharp critique of an alleged worldwide ‘business as usual

approach’ portrayed in the WCD. Whether this was a WCD aw, or

if signicant progress has occurred after the report, is not clear and no

longer relevant. What is clear is that a positive message on improved

decision making came out of the DDP exercise.

Another step forward is the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment

Forum (HSAF). This is a two-year project being undertaken by the

IHA, governments of developing and developed countries, NGOs, the

hydropower and nance sectors. At the end of 2010 it aims to have

a measurement tool for assessing hydropower sustainability, to be

endorsed by all members of the forum, which is practical, objective

and implementable. The HSAF acknowledges that without the WCD

process there might not be any HSAF today. It should not be seen to

be in conict with WCD or its recommendations as it takes many of

these on board. However, by focusing on operational implications,

HSAF provides an opportunity to resume and advance discussions

about sustainable hydropower among both supporters and critics of

the WCD recommendations. [6].

A DIFFICULT TASK

Following its ofcial launch, there were both supporters and critics of

the WCD’s nal report. Nelson Mandela put it quite eloquently at the

London meeting in November 2000: “It’s one thing to nd fault with

an existing system,” he said. “It’s another thing, altogether a more

difcult task, to replace it with an approach that is better.”

Both opponents and proponents of what has been called the big

dams debate, would agree that positive steps have been made over the

past decade. However gaining consensus with all parties has, and will

still prove to be, a difcult task. Just what will we be writing in ten

years from now, no one really knows. Only time will tell.

IWP& DC

Above: Community referendum on a dam project in Guatemala.

References

[1] Briscoe J, 2010. Viewpoint – Overreach and response: the politics of the

WCD and its aftermath. Water Alternatives 3(2), pp399-415.

[2] Chiramba T, Manyara P, 2010. WCD+10: Uptake, impact and

perspectives – A snapshot survey. Freshwater Ecosystems Unit, UNEP.

[3] Steiner A, 2010. Preface. Water Alternatives 3(2), pp1-2.

[4] Moore D, Dore J, Gyawali D 2010. The World Commission on Dams +10:

revisiting the Large Dams Controversy. Water Alternatives 3(2), pp3-13.

[5] Moore D, Speech at the World Water Week WCD +10 Forum, Stockholm

September 2010.

[6] Locher et al, 2010. Initiatives in the hydro sector post-World Commission

on dams – the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Forum. Water

Alternatives 3(2), pp43-57.

Water alternatives can be found at www.water-alternatives.org

14 NOVEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

WORLD COMMISSION ON DAMS - 10 YEARS ON

I

N 2001 the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD)

issued its nal comments about the World Commission on Dams’

report. In fact, the goals of dam construction that ICOLD insist

upon aim to achieve the maximum possible benets by minimis-

ing negative effects on social, environmental and ecological aspects,

including cultural relics, through the full and rational utilisation of

natural resources. The different kinds of schemes have to be carefully

and thoroughly studied and screened by current regulations in order

to attain a harmonious co-existence of mankind and nature. This

idea can be viewed in various ICOLD bulletins and publications, and

is something which is not signicantly different from the goals men-

tioned in the WCD report.

However, the WCD report overlooked the huge benefits and

improvements made on society and the environment by dam con-

struction. And in many aspects, the 26 guidelines proposed in the

report for the planning and implementation of future dams, don’t

fully take into account the special conditions and the specic develop-

ment phase of different countries. They are somewhat too idealistic.

Therefore, it is inappropriate to require all countries and all interna-

tional banking organisations to follow the same guidelines.

TEN YEARS LATER

Since the WCD report was published, ten years have gone by. We

are in a changing world. Issues of common concern include dealing

with an economic crisis, adapting to the impacts of climate change,

poverty alleviation and the mitigation of environmental degradation.

These remain challenges for us all. Out of these arise new require-

ments for dam and hydropower development.

ICOLD, throughout its 82-year history, has developed and evolved

in alignment with the requirements of mankind. It now has a world

reputation as the leading organisation in the eld of dam engineering

and water resources development. During the past century, ICOLD

has been glad to see that large dams have made an important contribu-

tion to the sustainable development of water and energy resources.

Today, sustainable development and sustainability of the life in

many parts of the world continue to be threatened by the scarcity of

supplies of water, food and energy: 1.1B people are still lacking access

to safe drinking water; 2.4B people are without the service of sanita-

tion; and 2B people are waiting for electricity supply.

We need more water and energy on one the hand; we need blue sky

and clean water on the other. Multi-purpose dams and reservoirs are

vital for human development.

A consensus on the role of dams and reservoirs in sustainable

development is being reached by the international community. The

point has been highlighted many times such as in the Johannesburg

Declaration on Sustainable Development, the Beijing Declaration

on Hydropower and Sustainable Development in 2004, the World

Declaration on Dam and Hydropower for African Sustainable

Development in 2008, and the Ministerial Declaration of the Fifth

World Water Forum in 2009.

More and more people are recognising that water resources devel-

opment is essential to achieve sustainable development. Insufcient

water storage facilities will delay our ability to respond to global

changes and to meet the Millennium Development Goals. In this con-

text, a developing country has more urgent need for water storage

facility development as the construction of water storage facilities is

not only a crucial matter relating to economic development but also

to survival and the alleviation of poverty.

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

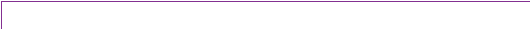

The United Nations has dened the Human Development Index. It

is a weighted average of the per capita GDP, health and education. It

reects quality of life and is an overall index used to measure the level

of socioeconomic development in UN member countries. Once we

compare and analyse per capita storage capacity index and the human

development index (HDI), we can nd out how dam/reservoir devel-

opment is related to socioeconomic development. (See Figure 1).

The UN Human Development Report also pointed out that ‘the

distribution of global water infrastructures is reversely proportional

to the distribution of global water risks’. To a certain extent, water

storage facility is usually an engine to drive socioeconomic develop-

ment on one hand and a development cause on the other. With popu-

lation growth and the acceleration of the urbanisation process, it is

predicted that water demands will increase at the speed of 64Bm

3

/yr.

Future estimates suggested that 47% of the total population on the

globe will live in places with a desperate water shortage.

To ensure water security, we must build adequate water storage

facilities. The view on accelerating water and hydropower develop-

ment will almost certainly be widely accepted under the circumstances

of severe challenges on water availability.

GOOD DEVELOPMENT

In the past, development and improving standards of living were

previously the main drivers behind dam projects. In recent years

hydropower has been rmly back on the agenda, as the focus has

changed to global warming and rising fuel prices etc. This will help

promote the positive image of good dam development. Water storage

is energy storage. Hydropower often pays for water storage and plays

an important role in modern power systems; currently accounting for

approximately 20% of world electricity.

Many counties have increased investment in hydropower. To date,

about 165 countries have already claried to further develop their hydro

potential. The proposed installed capacity already totals 33.8TW. In

developed countries the focal point for hydropower development has

already moved to rehabilitation, the reinforcement of constructed

hydropower plants to strengthen ood relief facilities for increasing the

capability of ood control, or adjusting its regulating target or mode

for the purpose of ecosystem protection and restoration. This has been

the case in countries in North America and Europe.

The World Commission on Dams report overlooked the benets of and improvements

made by dams to society, says ICOLD president Jia Jingsheng. In addition, its guidelines

were somewhat idealistic. However ten years on, ICOLD believes that the negative impacts

of project development should never be suppressed, overlooked or underestimated. The

construction and operation of dams and hydropower projects can no longer be considered

as a purely scientic and technical matter. A wide range of other aspects are involved today

Facing reality on dam development

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM NOVEMBER 2010 15

WORLD COMMISSION ON DAMS - 10 YEARS ON

For the developing world, such as countries in Asia and South

America, many countries stipulated ambitious plans for hydropower

development by 2025. For the less developing country, such as in

Africa, although they have abundant hydropower potential and the

desire for hydropower development, there are limitations on invest-

ment, and technical or political aspects, which still act as barriers for

developing hydropower.

At present, there are 1200 dams under the construction. Among

them more than 370 dams are above 370m high. The majority are

distributed in 55 countries in Asian and South American countries.

In this regard, during ICOLD’s 78th Annual Meeting in Hanoi in

2010 we successfully organised the First Round Table Meeting on

Dams and Hydropower for Sustainable Development in Africa.

Government representatives, nancial organisations, international

contractors, media, and delegates from Africa joined the discussion

for further action to help countries in Africa.

An Asian Declaration has also been drafted. Asia has great poten-

tial for hydropower but the percentage of hydropower generation

to its economical potential is still lower with a ratio about 25%. To

achieve a better development in the future, we intend to call for the

international community to make a greater contribution towards

dam and hydropower development in Asian countries.

CLIMATE CHANGE

In addition, hydropower can demonstrate its value in lower energy

consumption and GHG emissions, which are becoming more impor-

tant under global attention due to climate change. The concept of an

energy payback ratio enables us to better measure the overall benets

of different modes of energy development and better understand the

advantage of hydropower in conserving energy and reducing emis-

sions when dealing with climate change.

One way to compare different energy options is to calculate the so-

called life cycle Energy Payback Ratio. This is the ratio of total energy

produced during that system’s normal lifespan to the energy required

to build, maintain and fuel the system. The Energy Payback Ratio of

a power plant is dened as the total energy produced over the lifetime

of the plant divided by the energy needed to build, operate, fuel, and

decommission it. The calculating result (Gagnon, 2005) shows the

energy pay back ration of hydropower is above 170, which is much

higher than 18-34 for wind power, 3-5 for biological energy, 3-6 for

solar energy, and 14-16 for nuclear energy. It very clearly shows the

advantage of the hydropower (Figure 2).

THE RIGHT TO BENEFIT

While there is clearly a strong need for more water infrastructure, this

should not be at the expense of the ecosystem. Negative impacts should

never be suppressed, overlooked or underestimated, when promoting

future development. Prudent planning, decision making, project man-

agement and allocation of benets are as important as technical aspects.

In the light of this, the following four points are critical:

r First of all, our attitude to nature should shift away from simply

exploiting natural resources and adopting restoration measures,

but should aim to protect the natural environment at an early stage

of planning.

r Secondly, decision making should not only be based on technical

and economic feasibility, but also on social equity and environ-

mental requirements.

r Thirdly, project operation and management should not only

involve traditional techniques to ensure safety, but should also

play a role in protecting the ecosystem. Examples are ensuring

minimum ow, and appropriate operation of reservoirs.

r Finally, benet-sharing should be more inclusive, rather than just

relating to a region or state. All stakeholders should be involved.

One should remember that all members of society have the right

to benet from a project.

Attention to the social and environmental aspects of dams and reser-

voirs must be a priority, at the forefront of all our activities, in the same

way as concern for safety is invariably a top priority. But our greatest

efforts must be to look to the future. In doing so, ICOLD will continue

to act as a leading role in the eld of water and energy sustainable

development with cooperation and collaboration from within and out-

side the water sector as well as from the multiple interested parties.

‘Respecting the past, facing reality, and looking towards the future’

will be the key foundation to guide ICOLD forwards. In its continuing

effort to achieve a better future in all aspects of planning and construct-

ing dams, and to contribute in a practical way to sustainable develop-

ment, ICOLD has some specic actions planned over the next three

years. These include: 1) More activities to assist and support member

countries; 2) Capacity building especially for less developed countries;

3) Promotion of the world declaration on Dams and Hydropower for

Africa; 4) Joint preparation of a declaration on Dams and Hydropower

for Asia; 5) Promotion and wider dissemination of the ICOLD

Bulletins, proceedings and other work of the Commission; 6) Enhance

external communications, particularly in cases of emergencies; 7)

Increase ICOLD membership, by encouraging more countries to join,

and increasing the involvement of young engineers in ICOLD’s work;

8) Preparation of position statements on key issues; 9) Increase collabo-

ration with other organisations relating to water; 10) Presentations by

ICOLD at international events on current issues.

In summary, dams and hydropower will play a unique and invalu-

able role in our changing world. The construction and operation of a

dam and reservoir can no longer be considered as a purely scientic

and technical matter. A wide range of other aspects are involved today:

economic, social and environmental. So it is time for us to consolidate

our thinking, with a view to addressing and solving all the current chal-

lenges in the eld of dam engineering and hydropower.

Jia Jingsheng is the President of ICOLD.

He also is Vice President of the China Institute of Water

Resources and Hydropower Research

Reference

Gagnon, L. 2005 Energy Payback Ratio. Hydro-Quebec, Montreal

3200

2400

1600

800

0

>0.9 0.7– 0.8 0.6– 0.7 0.5– 0.60.8– 0.9

2924

2476

571

212

173

Human development index (HDI)

Storage capacity per capita (m

3

)

Coal in conventional

plant

Solar photovoltaic

Biomass plantations

Nuclear

Hydropower run of

river

Hydropower with

reservoir

Windpower

1.6

3.3

2.5

5.1

3

6

3

5

14

16

18

34

170

267

280

206

Low estimation

High estimation

050 100 150 200 250 300

Coal in CO2 capture

/storage

3200

2400

1600

800

0

>0.9 0.7– 0.8 0.6– 0.7 0.5– 0.60.8– 0.9

2924

2476

571

212

173

Human development index (HDI)

Storage capacity per capita (m

3

)

Coal in conventional

plant

Solar photovoltaic

Biomass plantations

Nuclear

Hydropower run of

river

Hydropower with

reservoir

Windpower

1.6

3.3

2.5

5.1

3

6

3

5

14

16

18

34

170

267

280

206

Low estimation

High estimation

050 100 150 200 250 300

Coal in CO2 capture

/storage

IWP& DC

Above: Figure 1 – Relationship between per capita storage capacity and HDI

Below: Figure 2 – A comparison of the energy payback ratio of power

16 NOVEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

PUMPED STORAGE

INGULA, SOUTH AFRICA

Ingula pumped storage scheme is located 23km northeast of Van

Reenen’s Pass on the border of Free State and KwaZulu Natal in

South Africa. The facility will generate power for the national grid.

Van Reenen’s Pass was selected out of three sites that were short-

listed from 90 locations. The scheme is being built on a 9000ha site

by state-owned Eskom at a cost of R8.9B. The work on the facility

began in November 2007 and is expected to be complete by 2014.

Development of the scheme was proposed in 2002 and was ini-

tially called the Braamhoek scheme, named after a tributary of

the Klip River. In March 2007, the scheme was renamed Ingula.

The basic design of the scheme began in 2004, when it was given

environmental clearance.

The project will comprise an upper and a lower reservoir. The

upper dam, named Bedford Dam, is located in the secondary of Wilge

River that ows into the Vaal River system. The dam is 810m long

and 40.9m high. It also has a 100m long emergency spillway, a dam

crest with elevation of 1740.6m and 8m crest width. It will have a

total capacity of 22.6Mm

3

and an active storage of 19.3Mm

3

.

The lower dam, named Braamhoek Dam, is situated in the second-

ary of Klip River that ows into the Thukela River. The length and

crest width of the dam are 331m and 5m. The dam is 38.6m high and

has a 40m long crest. The 0.5m dam wall height holds ood inows

to avoid 1:200-year ood dam spill. The lower reservoir will have a

26.3Mm

3

capacity and active storage of 21.9Mm

3

.

The reservoirs, 4.5km apart, will be connected by underground

waterways to a subterranean generating plant which will include four

342MW pump turbines from Voith Hydro.

A joint venture led by Italian firms Impregilo and CMC were

awarded a contract by Eskom Holdings in 2009 to construct the

underground works and reservoirs for the project. Construction

works on the scheme include caverns, tunnels, adits, shafts and pen-

stocks, installation of the pump-turbines, and construction of the

dams for the upper and lower reservoirs.

Power and automation technology group ABB won a $23M order

to supply an electrical balance of plant (eBoP) solution to the project

earlier this year. Key products to be supplied include the service

and auxiliary transformers, dry-type distribution transformers and

medium- and low-voltage switchgear.

As at September 2010, the progress on key works was as follows

(courtesy Eskom):

r Surge chambers 3 and 4: Completion of second stage support work

in progress. Top support 65% complete

r Surge chambers 1 and 2: Top widening in progress, 60%

complete.

r Tailrace tunnel: Advanced 82.95m downstream and 59.96m

upstream. Tunnel 63% complete

r Outlet structure: Construction has progressed to the tower section

with only the top slab remaining to be cast. Trashracks are partially

installed. Stop logs shall be installed before nally casting the top

slab. The structure was 90% complete.

r Machine hall: The second of two benches was 50% complete.

r Transformer hall: Work started on the rst of two benches.

r Main drainage gallery: Excavation work completed, with concrete

work on the invert commencing.

r Penstocks: No 4 is complete, with No 3 at 70%. Widening of the

anchor block is in progress.

LIMMERN (LINTHAL 2015), SWITZERLAND

Kraftwerke Linth-Limmern AG – a partnership between the canton

of Glarus and Axpo – is expanding its existing facilities under the

Linthal 2015 project to be able to ensure security of electricity supply

in the future. The core of the project is the Limmern pumped stor-

age power plant with a pump and turbine capacity of 1000MW.

Construction on the project commenced at the end of September

2009 and is expected to take almost seven years to complete in total.

IWP&DC presents details on ve important pumped storage schemes currently under

development or recently commissioned worldwide

Five in focus – new pumped

storage schemes

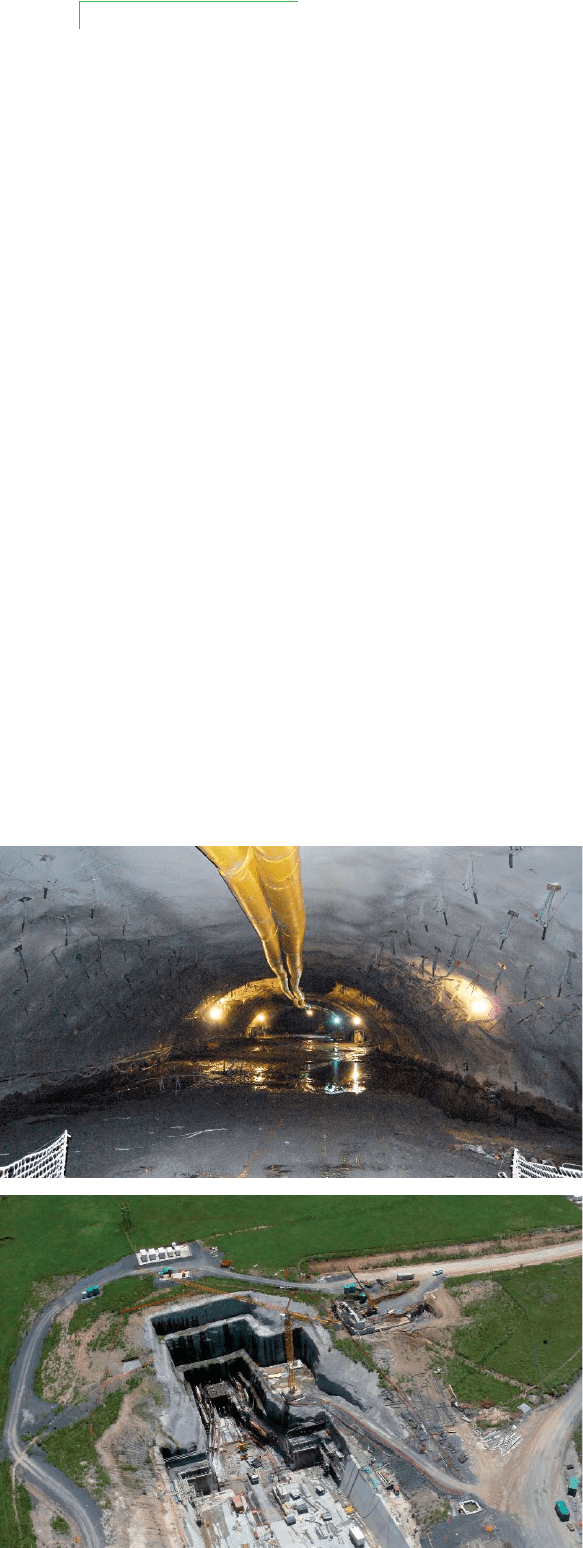

Top left: View of the Ingula machine hall in February 2010, courtesy of Eskom;

Bottom left: Photograph of the outlet structure also taken in February 2010

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM NOVEMBER 2010 17

PUMPED STORAGE

The commissioning of the rst generating unit is planned for 2015

and the last for 2016.

The project will pump water from the existing Limmern dam to

Lake Mutt; with the level of Lake Mutt to be raised as part of the

project. Depending on operating conditions and management of the

Limmern dam, the Limmern plant will have a drop of between 560m

and 710m.

Lake Mutt is a natural reservoir; the lake’s surface level will be

raised by up to 30m through the construction of a 1050m long con-

crete gravity wall. During turbine operations, water from Lake Mutt

will be collected from the inlet/outlet structure and channelled via the

570m long headwater pressure tunnel, which has an inner diameter

of 8m, in the direction of the pressure shafts. A service chamber with

two buttery control valves is located at the top of the pressure shafts.

The two reinforced pressure shafts are 1050m in length with an inner

diameter of 4m; they channel the water down a drop of 680m to the

machinery gallery.

Just before the machine gallery, each of the pressure shafts splits

into two headwater connecting tunnels that then lead to the four

turbines. There is a ball valve on the headwater side of each tur-

bine to control the operational, emergency and maintenance set-

tings. The water surge pressure created in the water system when

the shutoff device is activated is dampened by the surge chamber.

The water is channelled from the turbines to the Limmern dam via

the tailwater tunnels.

The four tailwater tunnels are reduced to two tunnels with a length

of 420m and 370m and an inner diameter of 6m. The water is chan-

nelled into the Limmern dam via the two inlet/outlet structures.

The underground gallery centre is made up of a machinery gallery

and a transformer gallery and the two are connected by various tun-

nels. The machinery gallery is 160m in length, 30m in breadth and

50m high, while the transformer gallery is 140m long, 20m wide and

25m high. A new access tunnel called ZS 1 will be built from Tierfehd

to the machinery gallery and will be 4000m in length with a bored

diameter of 8m. The access tunnel will be tted with a funicular rail-

way to transport heavy loads, and will facilitate the delivery of the

generator-transformer units to the site; each unit weighs 225 tonnes.

The four pumped storage units, to be supplied by Alstom Hydro,

will be installed in the machinery gallery; each unit is made up of a

single stage pump turbine with an installed pump and turbine output

of 250MW and a variable rotary asynchronous motor-generator

with the necessary support and ancillary equipment. The designed

throughput volume for the pump action is approximately 35m

3

/sec

and approximately 50m

3

/sec for the turbine action. The pump tur-

bine units are reversible Francis turbines. Each motor-generator is

coupled via its transformer to the 380kV substation. Two 380kV

cable systems lead from the substation to the new Tierfehd trans-

former substation via the ZS1 access tunnel.

A 17km long 380kV overhead line is being constructed from the

Tierfehd substation to connect the Limmern pumped storage plant to

the Swiss high voltage grid.

In June 2010, consulting rm Poyry was awarded a EUR 2.1M sur-

veying contract for the project. Pöyry’s tasks comprise the independ-

ent checking of all major geodetic surveying works as well as geodetic

deformation measurements and the monitoring of caverns, dam and

tunnel sections. Furthermore, Pöyry’s contract includes the geodetic

basic point network and the major setting-out of access tunnels, gal-

leries, caves, gravity dam, surge chamber, pressure shafts and associ-

ated structures. Pöyry’s task ends with the industrial surveying for the

installation of components such as turbines and steel structures.

ABB will provide electrical equipment, including transformers,

medium-voltage switchgears, and instrumentation and automa-

tion systems for the project, with Nexans to supply, install and

commission six 380kV XLPE-insulated underground cables. DSD-

Noell will design, supply and erect two penstocks for scheme.

LIMBERG II, AUSTRIA

Limberg II is being developed as an extension to the Kaprun project

by Verbund subsidiary, Austrian Hydro Power (AHP). The project

Above: Transporting a giant 33 tonne tunnelling machine via the first section

of the temporary cableway at the Limmern project. Below: Mooserboden stor-

age lake at the Limberg II project. Photograph copyright Neymayr, Verbund

18 NOVEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

PUMPED STORAGE

is a US$467M peak-load pumped storage project that, upon com-

pletion, will increase capacity at Kaprun from 353MW to 833MW.

The project is located in the southern part of the federal province of

Salzburg, north of the Glockner Group in the Kaprun Valley, near the

junction of the three regions of Salzburg, East Tyrol and Carinthia. It

will operate on the existing Mooserboden and Wasserfallboden reser-

voirs in the lower Kaprun valley. The reservoirs have a live storage of

81.2 and 84.9Mm

3

respectively, and a mean level difference of 366m

for pumped storage. The power conduit between Mooserboden and

Wasserfallboden will have a maximum ow of 140cm/sec The project

includes 7.5km of road tunnel and escape tunnel; a cavern measur-

ing 62m x 25m x 44m; a 4km-long, 7m-diameter headrace tunnel; a

750m-long, 5.5m-diameter inclined shaft; a 600m-long, 8m-diameter

tailrace tunnel; two valve chambers; and a surge tank.

A tunnel system measuring a total of 5.8km was erected during the

initial opening up of the construction site – with work completed in

record time and top tunnelling performances of up to 24m per day.

The transformer cavern (61m long, 15m wide, 16m high) and the

machine cavern, which is as large as the nave of St. Stephen’s cathe-

dral, were completely broken through in July and December 2007,

respectively. Once work has been completed on the machine cavern,

two reversible Francis turbines with a nominal capacity totalling

480MW will be installed. The units will be commissioned in 2011

and full operation should start in March 2012, with 1.3GWh annual

average production from pumped storage mode – the current plant

averages 670MkWh/yr. The fully automated plant will be monitored

from Kaprun’s main control room.

During construction of the scheme, AHP took great care to avoid

negative impacts on the environment and landscape. Only the access

buildings and storage areas for tunnel excavation material will be above

ground, with the project often being described as the ‘invisible plant’.

Key players in the project are:

r Hinteregger & Sohne: Technical Overhead

r Voith Hydro

r Andritz Hydro

r VAM GmbH & Co Anlagentechnik und Montagen

r Poyry Energy

r Arge Poyry Infra GmbH/Intergeo ZT GmbH

r Hans Kunz GmbH

r Alstom Hydro

r Litostroj

NANT DE DRANCE, SWITZERLAND

The Federal Environment Ministry licensed the EUR650M (US$9.3M)

Nant de Drance project in August 2008. Located between the towns

of Martigny and Chamonix in Valais, Nant is a joint venture between

Swiss utility Alpiq (54%), Federal Swiss Railways SBB (36%) and

municipal utility FMW (10%).

Atel (forerunner of Alpiq) and SBB rst applied to licence Nant in

summer 2006. Then the cost estimate was a more modest EUR500M

(US$695M). SBB came close to abandoning the project as raw material

and construction costs soared over the next 18 months. One condition

of the build and operate deal creating the Nant de Drance company,

agreed in November 2008 between the then joint partners, was the

need to rein in building and engineering costs before work began.

The plant is scheduled to come on-line in stages from 2015, with a

maximum 1500GWh annual output of peak load electricity – enough

to cover demand from 600,000 homes. The 380kV grid running from

Chatelard through the Rhone valley will also be modernised and

extended ahead of Nant’s completion.

The contract for construction work on Nant went to Groupement

Marti Implenia (GMI). The powerhouse will be built almost entirely

underground in a cavern between two existing reservoirs, Emosson

(1930m altitude) and Vieux Emosson (2205m altitude), on land

belonging to the Valais border municipality Finhaut. A 5.6km long

gallery will access the cavern at 1700m altitude in the Lower Valais.

Alstom Hydro will equip the new power station with four 157MW

vertical Francis reversible turbines, four 170 MVA vertical asynchro-

nous motor/generator units and further key equipment. Alstom will

also handle complete site delivery, erection, supervision and com-

missioning.

Alstom Hydro’s facilities in Grenoble, France and Birr, Switzerland

will be in charge of the engineering and manufacturing of the equip-

ment, to be delivered until 2017. A F Colenco is providing engineer-

ing services for the project.

DNESTROVSKAYA, UKRAINE

Ukraine has been investing in additional hydropower capacity as it

introduces much needed exibility into its ageing system. One of these

projects is the Dnestrovskaya pumped storage plant on the Dnyéstr

River, just downstream of Novodnestrovsk in Ukraine. The Dnyéstr

River rises in Ukraine, near Drohobych close to the border with

Poland, and ows toward the Black Sea. The plant was commissioned

in December 2009 by UkrHydroEnergo Open Joint Stock Company

(OJSC), a non-prot public organisation which brings together indi-

viduals and companies operating in hydropower in Ukraine.

The task of the Dnestrovskaya project is to regulate peak loads

in the electricity supply system, participate in frequency regula-

tion, and provide emergency power reserves. The plant has seven

421MW units and, when all units are operational, will have a total

capacity of 2947MW, making Dnestrovskaya the largest pumped

storage plant in Europe.

The control system on the plant has been supplied as a turn-

key project by Emerson Process Management in partnership with

Ukrainian Joint-Stock Company Enpaselectro and included the

supply of an Ovation expert control system along with the associated

project management, engineering, installation supervision, start-up

and commissioning services.

IWP& DC

Above: Views of construction work at the Nant De Drance project

%0&%.&.%+*+&+",'+2+. ++

4

#,%)#- * %&)*,)') *

,*&%#0*+')$ ,$(, '

$%+)&$+30. ++&+*,')

-0. +&0& )&%)+

&*+#%) *&)&%1

++##%)

,'#&*%0&,+

)) %%/ + %2+

2)*+)&,%&+2+ *

&%+...)0&)) "&&$

$

"

"

!

#

"

# %&)%+)0+&-$)). %. ##+"'#&%*+$)

. %%)*. ##%&+ 2## * &%*)2%#%%&+*,!++&##''#

20 NOVEMBER 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

PUMPED STORAGE

P

UMPED storage is a well-known energy storage technol-

ogy. The rapidly increasing renewable energy capacity in

the grid is acting as a driver for the growth of energy stor-

age technologies, and pumped storage in particular has a

role to play.

The countries which already have a higher penetration of renew-

able energy into the grid/or are planning for a large renewable

capacity, are also planning to ramp up their pumped storage capac-

ity at the same pace. Even companies with higher wind installa-

tion are looking to develop their own pumped storage plants for

the optimisation of renewable energy sources, while an increasing

trend in pumped storage installation can be observed in countries

with a higher renewable penetration plan.

Apart from the inbuilt characteristics of pumped storage; two

important factors are driving the development of pumped stor-

age power plants for energy storage. These are (i) compatibility of

pumped storage with intermittent renewable sources to optimise

their performance and (ii) advantages over other technologies for

energy storage.

Compatibility of pumped storage with intermittent renewable

sources

The intermittent nature of renewable energy sources such as wind

and solar is of benet to pumped storage power plant development.

Incorporating wind power into the grid could prove difcult just

because of bottlenecks in the grid and so the integration of energy stor-

age facilities with wind farms could be favourable to such investors.

With solar and wind power development forecast by various agen-

cies the world over, the amount of investment in storage technologies

is expected to grow exponentially. Europe and the US are aiming at

20% renewable penetration by 2020; largely with wind power.

Advantage over other energy storage technologies for energy storage

Currently pumped storage has the edge over other energy storage

technologies and may provide a solution to the issue of the inter-

mittent nature of renewables. Nowadays much is talked about the

development of other energy storage technologies but so far no other

storage technology meets the criteria to absorb the intermittent nature

of renewable energy sources on a larger scale. No other technology

has so far achieved a breakthrough in storing large amounts of energy

in a cost effective manner. Each energy storage technology is limited

in some fundamental way to meet the specic needs of high amounts

of energy storage.

Compressed air energy storage (CAES) and batteries can be thought

of as energy storage technologies to replace pumped hydro, but both

have their own limitations.

rA compressed air energy storage (CAES) system stores compressed

air under pressure in a naturally occurring underground cavern with

the help of motors. Currently there are only two commercial CAES

systems operating in the world with a third system in the develop-

ment stage (according to the Energy Storage Association, 2009).

The limitations of this technology are low energy efciency; it is

very site specic, and has lower storage in comparison with pumped

storage. With only two CAES systems operating, there currently is

no widespread knowledge about the technology.

rBatteries are most suitable for hybrid systems with smaller storage

needs and are not useful on a utility scale. Rechargeable batteries

store electricity in chemical energy. Though batteries are capable

of long term storage; factors like higher initial capital cost, a very

The conventional benets of pumped storage, coupled with its modern application of

integration with intermittent renewable energy technologies, are fuelling its development.

Purushottam Uniyal of business intelligence provider GlobalData reports

Old concept, new opportunities

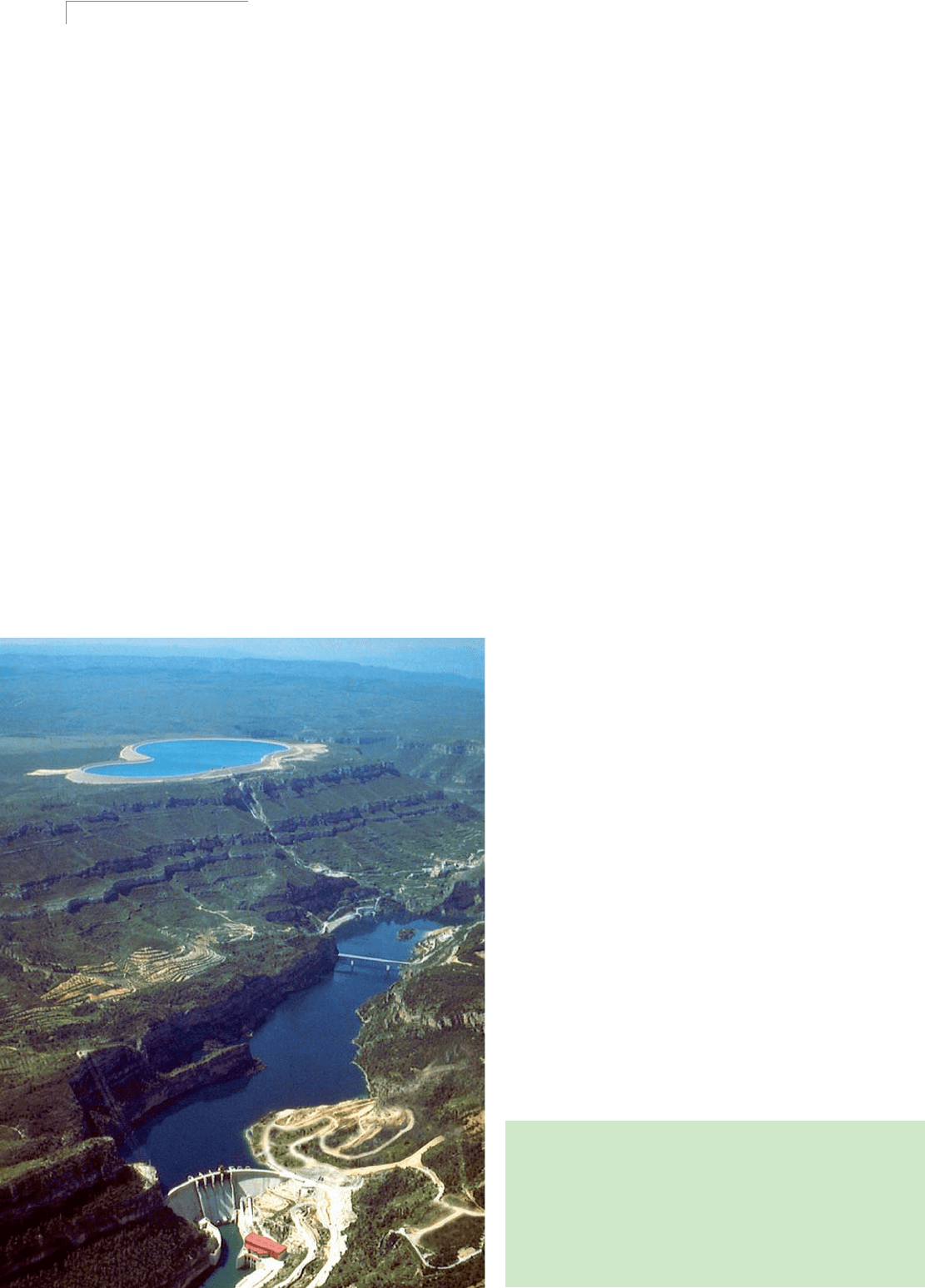

Below: View of La Muela pumped storage project in Spain.

Photograph courtesy of Iberdrola

New report from GlobalData

Old Concept – New opportunities is a new publication from GlobalData, a leading

provider of global business intelligence. The scope of this report includes:

r1VNQFETUPSBHFPQFSBUJOHQSJODJQMFTBOEFGàDJFODZ

r'BDUPSTGVFMMJOHUIFHSPXUIPGQVNQFETUPSBHFQMBOUT

r1VNQFETUPSBHFQMBOUTUPFNFSHFBTLFZFOFSHZTUPSBHFPQUJPO

r(SPXUIPGQVNQFETUPSBHFDBQBDJUZJONBKPSSFHJPOTBOEGVUVSFQMBOT

'PSNPSFEFUBJMTPSUPPCUBJOUIFSFQPSUWJTJUwww.globaldata.com