Ware C. Information Visualization: Perception for Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In the preparation stage, the problem-solver acquires the background information needed to

build a solution. Sometimes, preparation will involve a stage of exploratory data analysis. Visu-

alization can help through pattern discovery (discussed especially in Chapter 6). In this process,

the visual queries may initially be a loosely defined search for any significant pattern, becoming

more focused as the issues become better defined.

In the production stage, the problem-solver generates a set of potential solutions. A solution

often starts with a tentative suggestion, which is either rejected or later refined. Early theorists

proposed that the quantity of ideas, rather than the quality, was the overriding consideration

in the production of candidate solutions. However, experimental studies fail to support this

(Gilhooly, 1988). Generating ideas irrespective of their value is probably not useful.

Possibly the most challenging problem posed in data visualization systems is to support the

way sketchy diagrams are used by scientists and engineers in the production stage. Discoveries

and inventions made using table-napkin sketches are legendary. Here is a description of the role

of a diagram by an architectural theorist (Alexander, 1964):

Each constructive diagram is a tentative assumption about the nature of the context.

Like a hypothesis, it relates an unclear set of forces to one another conceptually; like a

hypothesis, it is usually improved by clarity and economy of notation. Like a hypothesis,

384 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

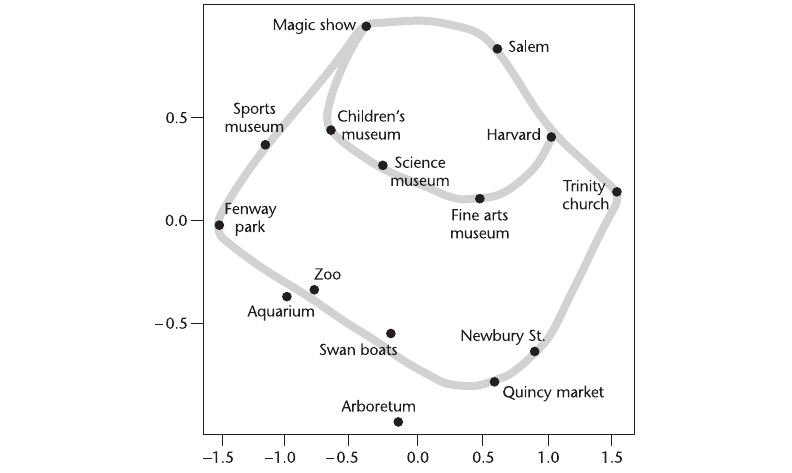

Figure 11.19 A trajectory map of tourist destinations in the Boston area, laid out according to the results of a

multidimensional scaling experiment (Lokuge et al., 1996).

ARE11 1/20/04 4:57 PM Page 384

it cannot be obtained by deductive methods, but only by abstraction and invention. Like a

hypothesis, it is rejected when a discrepancy turns up and shows that it fails to account

for some new force in the context.

If creativity is to be supported, the medium must afford tentative interactions. The lack of pre-

cision in quick, loose sketches actually allows for multiple interpretations. The fact that a line

can be interpreted in many different ways, as discussed in Chapter 6, can be a distinct benefit in

enabling a diagram to support multiple tentative hypotheses. The sketches people construct as

part of the creative process are rapid, not refined, and readily discarded. Giving a child high-

quality watercolor paper and paints is likely to inhibit creativity if the child is made aware of

the expense and cautioned not to “waste” the materials. Schumann et al. (1996) carried out an

empirical study of architectural perspective drawings executed in three different styles: a precise

line drawing, a realistically shaded image, and a sketch. All the drawings contained the same fea-

tures and level of detail. The sketch version was rated substantially higher on measures of ability

to stimulate creativity, changes in design, and discussions.

In the judgment stage, the problem-solver analyzes the potential solutions. This stage is an

exercise in quality control; as fast as hypotheses are created and patterns are discovered, most

must be rejected. In a visualization system used for data mining, the user may discover large

numbers of patterns but will also be willing to reject them almost as rapidly as they are discov-

ered. Some will already be known, some will be irrelevant to the task at hand, only a few will

be novel, and even fewer will lead to a practical solution. Many judgment aids are not visual;

for example, statistical tools can be used to test hypotheses formally. But when visualization is

part of the process, it should not be misleading or hide important information.

The challenge for problem-solving interfaces is to support the rapid creation of loose

sketches, the ability to modify them, and the ability to discard all or some of them. All this must

be done with an interface so simple that it does not intrude on the visual thinking process.

Conclusion

The best visualizations are not static images to be printed in books, but fluid, dynamic artifacts

that respond to the need for a different view or for more detailed information. In some cases,

the visualization can be an interface to a simulation of a complex system; the visualization, com-

bined with the simulation, can create a powerful cognitive augmentation. An emerging view of

human–computer interaction considers the human and the computer together as a problem-

solving system. The visualization is a two-way interface, although highly asymmetric, with far

higher bandwidth communication from the machine to the human than in the other direction.

Because of this asymmetry in data rates, cognitive support systems must be constructed that are

semiautomatic, with only occasional nudges required from users to steer them in a desired direc-

tion. The high-bandwidth visualization channel is then used to deliver the results of modeling

exercises and database searches.

Thinking with Visualizations 385

ARE11 1/20/04 4:57 PM Page 385

At the interface, the distinction between input and output becomes blurred. We are accus-

tomed to regarding a display screen as a passive output device and a mouse as an input device.

This is not how it is in the real world, where many things work both ways. A sheet of paper or

a piece of clay can both record ideas (input) and display them (output). The coupling of input

and output can also be achieved in interactive visualization. Each visual object in an interactive

application can potentially provide output as a representation of data and also potentially receive

input. Someone may click on it with a mouse to retrieve information or may use it as an inter-

face to change the parameters of a computer model. The ultimate challenge for this kind of highly

interactive information visualization is to create an interface that supports creative sketching of

ideas, affording interactive sketching that is as fluid and inconsequential as the proverbial paper-

napkin sketch.

The person who wishes to design a visualization must contend with two sets of conflicting

forces. On the one hand, there is the requirement for the best possible visual representation, tai-

lored exactly to the problem to be solved. On the other hand, there is the need for consistency

in representation any time that two or more people work on a problem. This need is even greater

when large, international organizations have a common set of goals that demand industrywide

visualization standards. At the stage of new discoveries in information visualizations, standard-

ization is the enemy of innovation and innovation is the enemy of standardization. Thus it is

important to get the research done before the standards are formed, otherwise it will be too late.

These are exciting times for information visualization, because we are still in the discovery

phase, although this phase will not last for long. In the next few years, the wild inventions that

are now being implemented will become standardized. Like clay sculptures that have been baked

and hardened, the novel data visualization systems of today’s laboratory will become cultural

artifacts, everyday tools of the information professional.

386 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

ARE11 1/20/04 4:57 PM Page 386

APPENDIX A

Changing Primaries

387

This appendix describes the operation of transforming one set of primaries into another. The

mathematical name for this operation is a change of basis.

To convert a color from one set of primary lights to another, it is first necessary to define a

conversion between the primaries themselves. We can think of this as matching each of the new

primary lights using the old primary system. Suppose we designate our original set of primaries

P

1

, P

2

, and P

3

and the new set of primaries Q

1

, Q

2

, and Q

3

. We now use our original primaries

to create matches with each of the new primaries in turn. Let us call the amount of each of the

P primaries c

ij

.

Thus,

(A.1)

If we denote the matrix of c

ij

values C, then

(A.2)

To reverse the transformation, invert the matrix:

(A.3)

PCQ∫

-1

PCQ=

QcPcPcP

QcPcPcP

QcPcPcP

1111122133

2211222233

3311322333

∫++

∫++

∫++

AREApp 1/20/04 4:55 PM Page 387

This same matrix can now be used to convert any set of values expressed in one set of primaries

to the other set of primaries. Thus, the values p

1

, p

2

, and p

3

represent the amounts of the lights

in primary system P needed to make a match.

(A.4)

Then we can calculate the values q in primary system Q simply by solving

(A.5)

qCp=

Sample ∫++pP pP pP

11 22 33

388 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

AREApp 1/20/04 4:55 PM Page 388

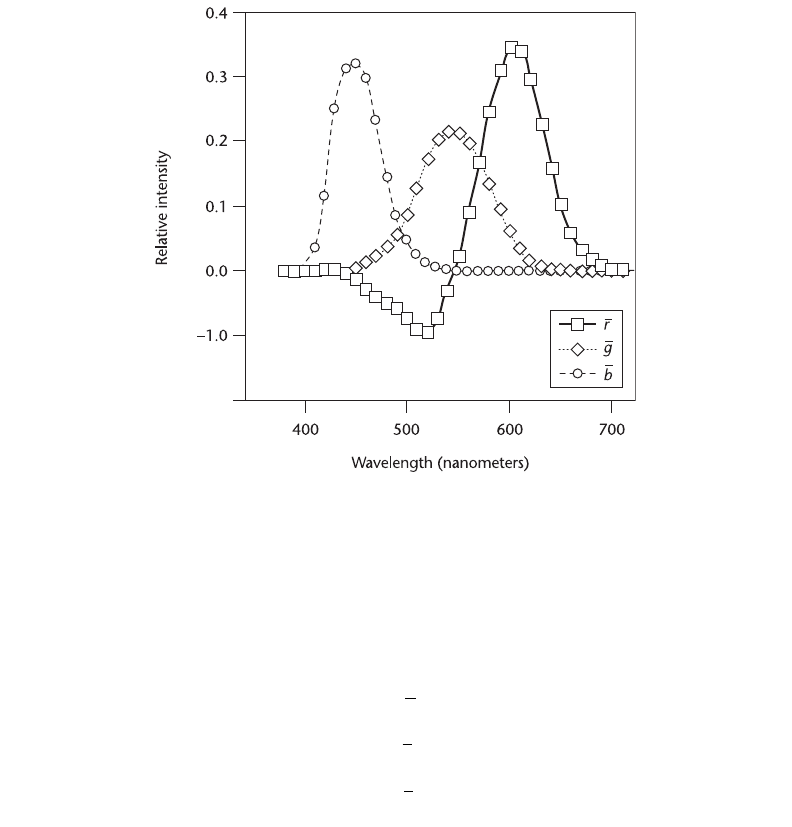

To determine a standard observer, a set of red, green, and blue lamps is used by a number of

representative subjects to match all the pure colors of the spectrum. The result is called a set of

color-matching functions. The set of color-matching functions for the Commission Internationale

de l’Éclairage (CIE) standard observer is illustrated in Figure B.1. They were obtained with red,

green, and blue pure spectral hues at 700, 546, and 436 nanometers, respectively, using a number

of trained observers. Notice that there are negative values in these functions. These exist for the

reasons discussed in Chapter 4. It is not possible to match directly all spectral lights with these,

or any other, primaries.

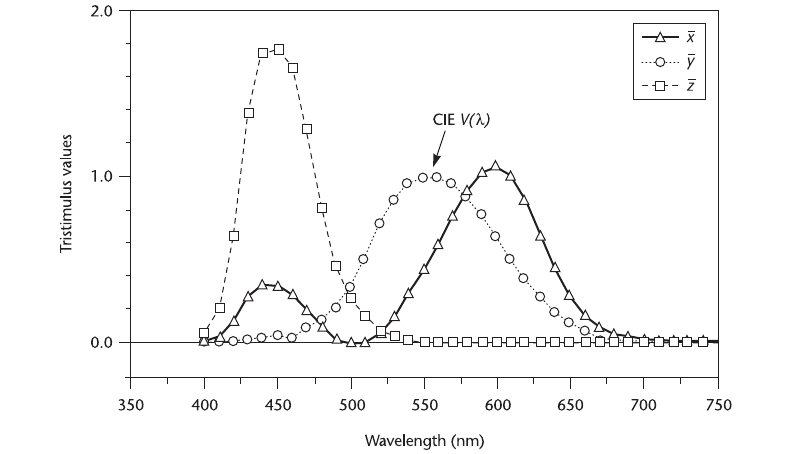

For a number of reasons, the CIE chose not to use the standard-observer color-matching

functions directly as the color standard, although it would have been perfectly legitimate to do

so. Instead, they chose a set of abstract primaries called the XYZ tristimulus values and trans-

formed the original color-matching functions into this new coordinate system. The process is the

transformation from one coordinate system to another, as described in Appendix A. The trans-

formed color-matching functions are illustrated in Figure B.2.

The CIE XYZ tristimulus values have the following properties:

1. All tristimulus values are positive for all colors. To achieve this, it was necessary to create

primaries that do not correspond to any real lights. The XYZ primary axes are purely

abstract concepts. However, this model has the advantage that all perceivable colors fall

within the CIE gamut. They are, in effect, a set of virtual primaries.

2. The X and Z tristimulus values have zero luminance. Only the Y tristimulus value

contains luminance information, and the color-matching function (y¯) is the same as the

V(l) function, discussed in Chapter 3.

To determine the XYZ tristimulus values for a given patch of light, we integrate the energy

distribution with the three x¯,y¯,z¯ color-matching functions that define the CIE standard. Note that

APPENDIX B

CIE Color Measurement System

389

AREApp 1/20/04 4:55 PM Page 389

this is a generalization of the process of obtaining luminance described in Chapter 3—only here,

we obtain three values to fully specify a color:

(B1.1)

If K

m

= 680 lumens/watt and E(l) is measured in watts per unit area solid angle (steradians),

then Y gives luminance.

This appendix provides only a very brief introduction to the complex and technical subject

of colorimetry. Many important issues have been neglected that must be taken into account in

serious color measurement. One issue is whether the light to be measured is an extended source,

XKExd

YKEyd

ZKE zd

m

m

m

=

(

)

=

(

)

=

(

)

Ú

Ú

Ú

ll

ll

ll

l

l

l

l

l

l

390 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

Figure B.1 The color-matching functions that define the CIE 1931 standard observer. To obtain these, each pure

spectral wavelength was matched by a mixture of three primary lights.

AREApp 1/20/04 4:55 PM Page 390

such as a monitor, in which case we measure in light emitted per unit area (candelas per square

meter), or a lamp, in which case we measure total light output in all directions.

The subject becomes still more complex when we consider the measurement of surface colors;

the color of the illuminating source must be taken into account, and we can no longer use a

trichromatic system. Fortunately, computer monitors, because they emit light, do allow us to use

a trichromatic system. The reader who intends to get involved in serious color measurement

should obtain one of the standard textbooks, such as Wyszecki and Stiles (1982) or Judd and

Wyszecki (1975).

CIE Color Measurement System 391

Figure B.2 The CIE tristimulus functions used to define the color of a light in XYZ tristimulus coordinates.

AREApp 1/20/04 4:55 PM Page 391

This page intentionally left blank

There is a hierarchy of value in research. The ultimate goal of the scientist is to discover an

immutable truth that will form the foundation for a new way of understanding the world. Applied

researchers must often be satisfied with more humble objectives; sometimes it may be necessary

to show that soon-to-be-obsolete interface A is better in some small way than soon-to-be-

obsolete interface B. Between these two scenarios are many graduations. A research-based design

guideline is something that can be of enduring value. A rough continuum of value exists, depend-

ing on the research goals. The following list starts with those goals that are most valuable.

Research Goals

Uncover fundamental truths and test theories. This is the holy grail of research—a

fundamental truth that forever changes how we think of the world. Even small truths are

to be prized. Because visualization techniques often produce patterns that do not exist in

nature, or rarely do, studies of such techniques can be part of the new discipline of

information psychophysics. Cognitive modeling of the way people interact with the

interfaces to information systems is an important part of cognitive systems theory; and

because all human intellectual achievements are ultimately the products of cognitive

systems, not individuals alone, lasting truths may be achieved.

Discover the nature of the world. The early stages of science can be like butterfly collecting. It

is necessary to get a feeling for the range of phenomena to be encompassed before

developing theories. Some areas of perception are still like this. For example, the

perception of patterns in motion is still at an early stage. The application of motion in

visualization similarly lags.

APPENDIX C

The Perceptual Evaluation

of Visualization Techniques

and Systems

393

AREApp 1/20/04 4:55 PM Page 393