Ware C. Information Visualization: Perception for Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Elision Techniques

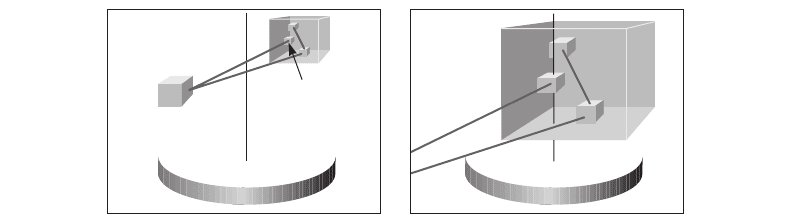

In visual elision, parts of a structure are hidden until they are needed. Typically, this is achieved

by collapsing a large graphical structure into a single graphical object. This is an essential com-

ponent of the Bartram et al. (1994) system, illustrated in Figure 10.12, and of the NV3D system

(Parker et al., 1998; see Figure 8.25). In these systems, when a node is opened, it expands to

reveal its contents.

The elision idea can be applied to text as well as to graphics. In the generalized fish-eye tech-

nique for viewing text data (Furnas, 1986), less and less detail is shown as the distance from the

focus of interest increases. For example, in viewing code, the full text is shown at the focus;

farther away, only the subroutine headers are made visible, and the code internal to the sub-

routine is elided.

Elision in visualization is analogous to the cognitive process of chunking, discussed earlier,

whereby small concepts, facts, and procedures are cognitively grouped into larger “chunks.”

Replacing a cluster of objects that represents a cluster of related concepts with a single object is

very like chunking. This similarity may be the reason that visual elision is so effective.

Multiple Windows

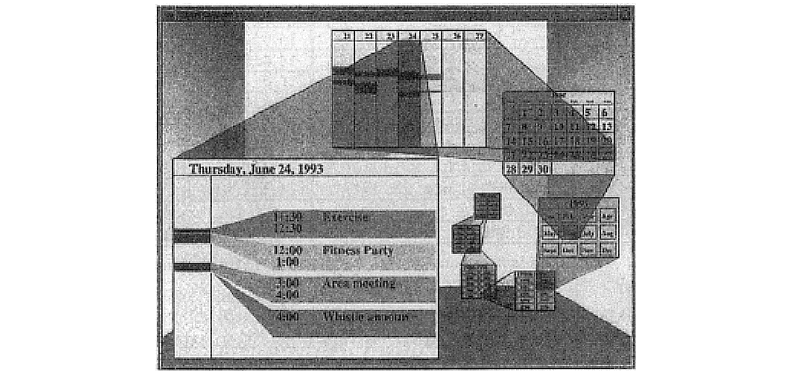

It is common, especially in mapping systems, to have one window that shows an overview and

several others that show expanded details. The major perceptual problem with the multiple-

window technique is that detailed information in one window is disconnected from the overview

(context information) shown in another. A solution is to use lines to connect the boundaries of

the zoom window to the source image in the larger view. Figure 10.17 illustrates a zooming

window interface for an experimental calendar application. Multiple windows show day, month,

and year views in separate windows (Card et al., 1994). The different windows are connected

by lines that integrate the focus information in one table within the context provided by another.

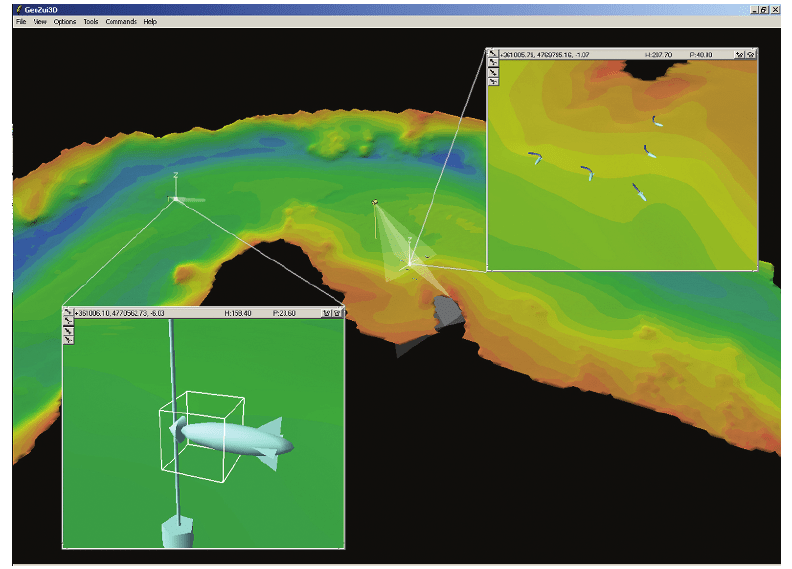

Figure 10.18 shows the same technique used in a 3D zooming user interface. The great advan-

344 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

Figure 10.16 In the NV3D systems (Parker et al., 1998), clicking and holding down the mouse causes the environment

to be smoothly scaled as the selected point is moved to the center of the 3D workspace.

ARE10 1/20/04 4:52 PM Page 344

tage of the multiple-window technique over the others listed previously is that it is both nondis-

torting and able to show focus and context simultaneously.

Rapid Interaction with Data

In a data exploration interface, it is important that the mapping between the data and its visual

representation be fluid and dynamic. Certain kinds of interactive techniques promote an experi-

ence of being in direct contact with the data. Rutkowski (1982) calls it the principle of trans-

parency; when transparency is achieved, “the user is able to apply intellect directly to the task;

the tool itself seems to disappear.” There is nothing physically direct about using a mouse to drag

a slider on the screen, but if the temporal feedback is rapid and compatible, the user can obtain

the illusion of direct control. A key psychological variable in achieving this sense of control is

the responsiveness of the computer system. If, for example, a mouse is used to select an object

or to rotate a cloud of data points in 3D space, as a rule of thumb visual feedback should

be provided within 1/10 second for people to feel that they are in direct control of the data

(Shneiderman, 1987).

Interactive Data Display

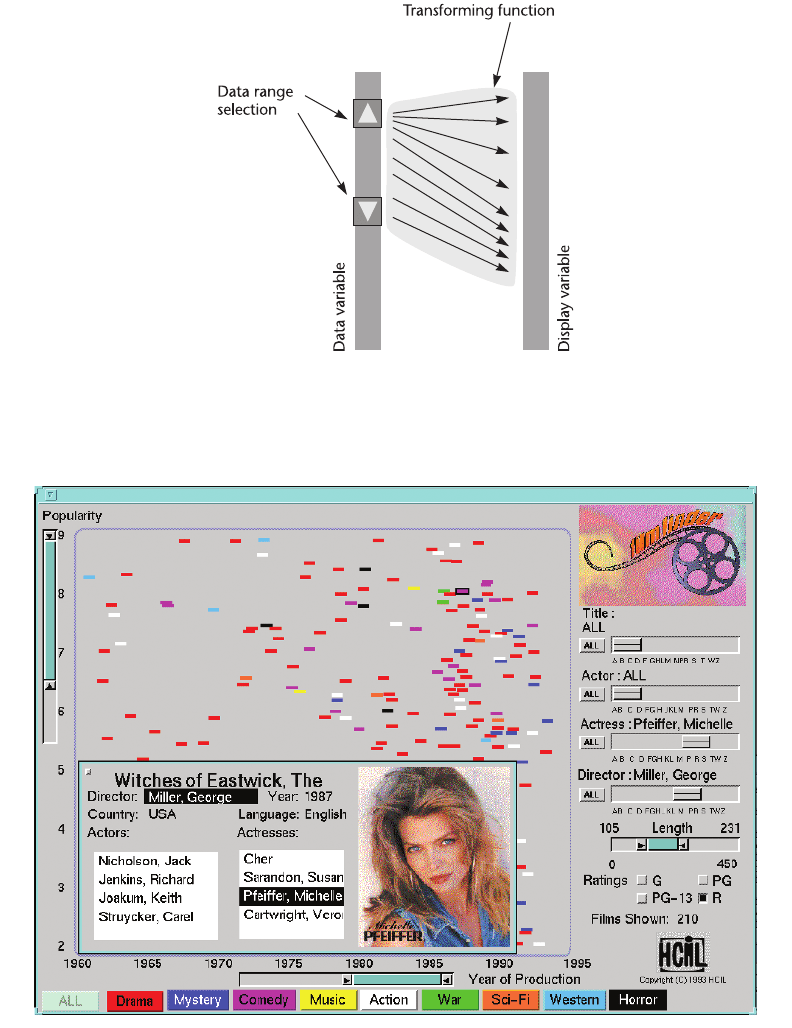

Often data is transformed before being displayed. Interactive data mapping is the process of

adjusting the function that maps the data variables to the display variables. A nonlinear mapping

Interacting with Visualizations 345

Figure 10.17 The spiral calendar (Card et al., 1994). The problem with multiple-window interfaces is that information

becomes visually fragmented. In this application, information in one window is linked to its context within

another by a connecting transparent overlay.

ARE10 1/20/04 4:52 PM Page 345

between the data and its visual representation can bring the data into a range where patterns are

most easily made visible. Figure 10.19 illustrates this concept. Often the interaction consists of

imposing some transforming function on the data. Logarithmic, square root, and other functions

are commonly applied (Chambers et al., 1983). When the display variable is color, techniques

such as histogram equalization and interactive color mapping can be chosen (see Chapter 4). For

large and complex data sets, it is sometimes useful to limit the range of data values that are

visible and mapped to the display variable; this can be done with sliders.

Ahlberg et al. (1992) call this kind of interface dynamic queries and have incorporated it

into a number of interactive multivariate scatter-plot applications. By adjusting data range sliders,

subsets of the data can be isolated and visualized. An example is given in Figure 10.20, showing

a dynamic query interface to the Film Finder application (Ahlberg et al., 1992). Dragging the

346 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

Figure 10.18 The GeoZui3D system allows for subwindows to be linked in a variety of ways (Plumlee and Ware, 2003).

In this illustration the focus of one subwindow is linked to an undersea vehicle docking. A second

subwindow provides an overview of a group of undersea vehicles. The faint translucent triangles in the

overview show the position and direction of the subwindow views.

ARE10 1/20/04 4:52 PM Page 346

Figure 10.19 In a visualization system, it is often useful to change interactively the function that maps data values to a

display variable.

Figure 10.20 The Film Finder application of Ahlberg and Shneiderman (1987) used dynamic query sliders to allow rapid

interactive updating of the set of data points mapped from a database to the scatter-plot display in the

main window. Courtesy of Matthew Ward.

ARE10 1/20/04 4:52 PM Page 347

Year of Production slider at the bottom causes the display to update rapidly the set of films shown

as points in the main window.

Another interactive technique is called brushing (Becker and Cleveland, 1987). This enables

subsets of the data elements to be highlighted interactively in a complex representation. Often

data objects, or different attributes of them, simultaneously appear in more than one display

window, or different attributes can be distributed spatially within a single window. In brushing,

a group of elements selected through one visual representation becomes highlighted in all the dis-

plays in which it appears. This enables visual linking of components of heterogeneous complex

objects. For example, data elements represented in a scatter plot, a sorted list, and a 3D map can

all be visually linked when simultaneously highlighted.

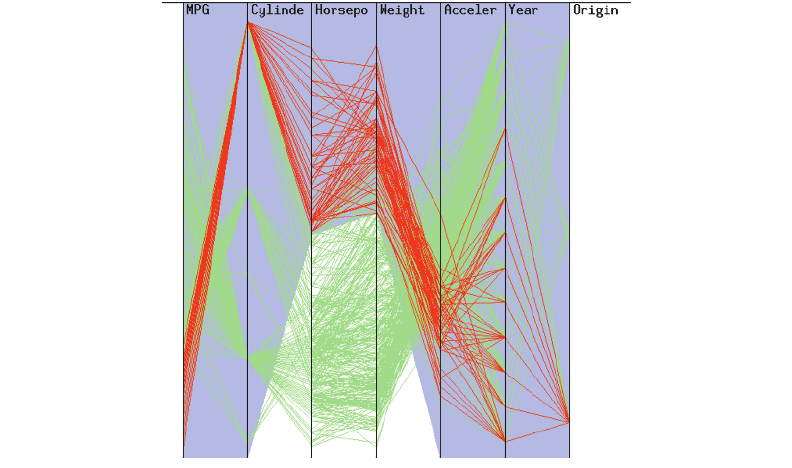

Brushing works particularly well with a graphical display technique called parallel coordi-

nates (Inselberg and Dimsdale, 1990). Figure 10.21 shows an example in which a set of auto-

mobile statistics are displayed: miles per gallon, number of cylinders, horsepower, weight, and

so on. A vertical line (parallel coordinate axis) is used for each of these variables. Each auto-

mobile is represented by a vertical height on each of the parallel coordinates, and the entire auto-

mobile is represented by a compound line running across the graph, connecting all its points. But

because the pattern of lines is so dense, it is impossible to trace any individual line visually and

348 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

Figure 10.21 In a parallel-coordinates plot, each data dimension is represented by a vertical line. This example

illustrates brushing. The user can interactively select a set of objects by dragging the cursor across

them. From: XmdvTool (http://davis.wpi.edu/~xmdv). Courtesy of Matthew Ward (1990).

ARE10 1/28/04 4:07 PM Page 348

thereby understand the characteristics of a particular automobile. With brushing, a user can select

a single point on one of the variables, which has the result of highlighting the line connecting all

the values for that automobile. This produces a kind of visual profile. Alternatively, it is

possible to select a range on one of the variables, as illustrated in Figure 10.21, and all the lines

associated with that range become highlighted. Once this is done, it is easy to understand

the characteristics of a set of automobiles (those with low mileage, in this case) across all the

variables.

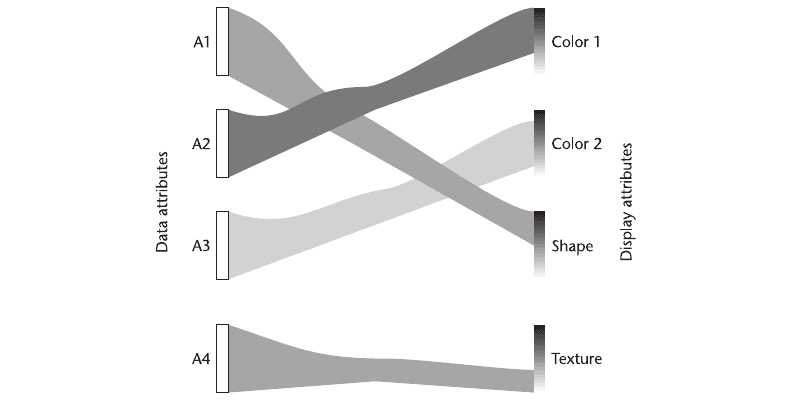

As discussed in Chapter 5, it is possible to map different data attributes to a wide variety of

visual variables: position, color, texture, motion, and so on. Each different mapping makes some

relationships more distinct and others less distinct. Therefore, allowing a knowledgeable user to

change the mapping interactively can be an advantage. (See Figure 10.22.) Of course, such

mapping changes are in direct conflict with the important principle of consistency in user inter-

face design. In most cases, only the sophisticated visualization designer should change display

mappings.

Conclusion

This chapter has been about the how to make the graphic interface as fluid and transparent as

possible. Doing so involves supporting eye–hand coordination, using well-chosen interaction

metaphors, and providing rapid and consistent feedback. Of course, transparency comes from

Interacting with Visualizations 349

Figure 10.22 In some interactive visualization systems, it is possible to change the mapping between data attributes

and the visual representation.

ARE10 1/20/04 4:52 PM Page 349

practice. A violin has an extraordinarily difficult user interface, and to reach virtuosity may take

thousands of hours, but once virtuosity is achieved, the instrument will have become a trans-

parent medium of expression. This highlights a thorny problem in the development of novel inter-

faces. It is very easy for the designer to become focused on the problem of making an interface

that can be used rapidly by the novice, but it is much more difficult to research designs for the

expert. It is almost impossible to carry out experiments on expert use of radical new interfaces

for the simple reason that no one will ever spend enough time on a research prototype to become

truly skilled.

Having said that, efforts to refine the user interface are extremely important. One of the

goals of cognitive systems design is to tighten the loop between human and computer, making it

easier for the human to obtain important information from the computer via the display. Simply

shortening the amount of time it takes to select some piece of information may seem like a small

thing, but information in human visual and verbal working memories is very limited; even a few

seconds of delay or an increase in the cognitive load, due to the difficulty of the interface, can

drastically reduce the rate of information uptake by the user. When a user must stop thinking

about the task at hand and switch attention to the computer interface itself, the effect can be

devastating to the thought process. The result can be the loss of all or most of the cognitive

context that has been set up to solve the real task. After such an interruption, the train of thought

must be reconstructed, and research on the effect of interruptions tells us that this can drasti-

cally reduce cognitive productivity (Field and Spence, 1994; Cutrell et al., 2000).

350 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

ARE10 1/20/04 4:52 PM Page 350

CHAPTER 11

Thinking with Visualizations

351

One way to approach the design of an information system is to consider the cost of knowledge.

Pirolli and Card (1995) drew an analogy with the way animals seek food to gain insights about

how people seek information. Animals minimize energy expenditure to get the required gain in

sustenance; humans minimize effort to get the necessary gain in information. Foraging for food

has much in common with the seeking of information because, like edible plants in the wild,

morsels of information are often grouped, but separated by long distances in an information

wasteland. Pirolli and Card elaborated the idea to include information “scent”—like the scent

of food, this is the information in the current environment that will assist us in finding more suc-

culent information clusters.

The result of this approach is a kind of cognitive information economics. Activities are ana-

lyzed according to the value of what is gained and the cost incurred. There are two kinds of

costs: resource costs and opportunity costs (Pirolli, 2003). Resource costs are the expenditures

of time and cognitive effort incurred. Opportunity costs are the benefits that could be gained by

engaging in other activities. For example, if we were not seeking information about information

visualization, we might profitably be working on software design.

In some ways, an interactive visualization can be considered an internal interface between

human and computer components in a problem-solving system. We are all becoming cognitive

cyborgs in the sense that a person with a computer-aided design program, access to the Internet,

and other software tools is capable of problem-solving strategies that would be impossible for

that person acting unaided. A businessman plotting projections based on a spreadsheet business

model can combine business knowledge with the computational power of the spreadsheet to plot

scenarios rapidly, interpret trends visually, and make better decisions.

In this chapter, our concern is with the economics of cognition and the cognitive cost of

knowledge. Human attention is a very limited resource. If it is taken up with irrelevant visual

noise, or if the rate at which visual information is presented on the screen poorly matches the

rate at which people can process visual patterns, then the system will not function well.

ARE11 1/20/04 4:56 PM Page 351

There are two fundamental ways in which visualizations support thinking: first, by sup-

porting visual queries on information graphics, and second, by extending memory. For visual

queries to be useful, the problem must first be cast in the form of a query pattern that, if seen,

helps solve part of the problem. For example, finding a number of big red circles in a GIS display

may indicate a problem with water pollution. Finding a long, red, fairly straight line on a map

can show the best way to drive between two cities. Once the visual query is constructed, a visual

search strategy, through eye movements and attention to relevant patterns, provides answers.

Memory extension comes from the way a display symbol, image, or pattern can rapidly

evoke nonvisual information and cause it to be loaded from long-term memory into verbal-

propositional processing centers.

This chapter presents the theory of how we think with visualizations. First, the memory and

attention subsystems are described. Next, visual thinking is described as a set of embedded

processes. Throughout, guidelines are provided for designing visual decision support systems.

Memory Systems

Memory provides the framework that underlies active cognition, whereas attention is the motor.

As a first approximation, there are three types of memory: iconic, working, and long-term. There

may also be a fourth, intermediate store that determines what from working memory finds its

way into long-term memory. Iconic memory is a very brief image store, holding what is on the

retina until it is replaced by something else or until several hundred milliseconds have passed

(Sperling, 1960). Long-term memory is the information that we retain from everyday experience,

perhaps for a lifetime. Consolidation of information into long-term memory only occurs,

however, when active processing is done to integrate the new information with existing knowl-

edge (Craik and Lockhart, 1972). Visual working memory holds the visual objects of immediate

attention. These can be either external or mental images. In computer science terms, this is a reg-

ister that holds information for the operations of visual cognition.

Visual Working Memory

The most critical cognitive resource for visual thinking is called visual working memory. Theo-

rists disagree on details of exactly how visual working memory operates, but there is broad agree-

ment on basic functionality and capacity—enough to provide a solid foundation for a theory of

visual thinking. Closely related alternative concepts are the visuospatial sketchpad (Marr, 1982),

visual short-term memory (Irwin, 1992), and visual attention (Rensink, 2002). Here is a list of

some key properties of visual working memory:

•

Visual working memory is separate from verbal working memory.

•

Capacity is limited to a small number of simple visual objects and patterns, perhaps three

to five simple objects.

352 INFORMATION VISUALIZATION: PERCEPTION FOR DESIGN

ARE11 1/28/04 4:08 PM Page 352

•

Positions of objects are stored in an egocentric map. Perhaps nine locations are stored, but

only three to five are linked to specific objects.

•

Attention controls what visual information is held and stored.

•

The time to change attention is about 100msec.

•

The semantic meaning or gist of an object or scene (related more to verbal working

memory) can be activated in about 100msec.

•

For items to be processed into long-term memory, deeper semantic coding is needed.

Working memory is not a single system; rather, it has a number of interlinked but separate com-

ponents. There are separate systems for processing auditory and visual information, as well as

subsystems for body movements and verbal output (Thomas et al., 1999). There may be addi-

tional stores for sequences of cognitive instructions and for motor control of the body. Kieras

and Meyer (1997), for example, proposed an amodal control memory, containing the operations

needed to accomplish current goals, and a general-purpose working memory, containing other

miscellaneous information. A similar control structure is called the central executive in

Baddeley and Hitch’s model (1974), illustrated in Figure 11.1.

A detailed discussion of nonvisual working memory processes is beyond the scope of this

book. Complete overview models of cognitive processes, containing both visual and nonvisual

subsystems can be found in the Anderson ACT-R model (Anderson et al., 1997) and the execu-

tive process interactive control (EPIC) developed by Kieras and his coworkers (Kieras and Meyer,

1997). The EPIC architecture is illustrated in Figure 11.2. Summaries of the various working

memory theories can be found in Miyake and Shah (1999).

That visual thinking results from the interplay of visual and nonvisual memory systems

cannot be ignored. However, rather than getting bogged down in various theoretical debates

about particular nonvisual processes, which are irrelevant to the perceptual issues, we will here-

after refer to nonvisual processes generically as verbal-propositional processing.

It is functionally quite easy to separate visual and verbal-propositional processing. Verbal-

propositional subsystems are occupied when we speak, whereas visual subsystems are not. This

allows for simple experiments to separate the two processes. Postma and De Haan (1996) provide

a good example. They asked subjects to remember the locations of a set of easily recognizable

objects—small pictures of cats, horses, cups, chairs, tables, etc.—laid out in two dimensions on

a screen. Then the objects were placed in a line at the top of the display and the subjects were

Thinking with Visualizations 353

Verbal working

memory

Central

exectutive

Visual working

memory

Figure 11.1 The multicomponent model of working memory of Baddeley and Hitch (1974).

ARE11 1/20/04 4:56 PM Page 353