Tsebelis G. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

311

the empirical level I used two shortcuts. In Chapter 7 I explained why it was difficult to identify

the status quo and used the position of the previous government as a proxy. In Chapter 8 I used

the same approximation but the justification was more appropriate, since it is quite frequent that

the default solution for not voting a budget on time is the automatic or quasi automatic adoption

of the previous year’s budget.

I explained that any attempt to include the status quo in empirical work has to be a

posteriori, that is define what the status quo is only after the new legislation passes. The reason is

that new legislation in an area (say social security) may or may not include provisions modifying

several bills. For example, the new Social Security bill may include provisions about mental

health. This subject may have existed in other pieces of legislation, or it may not have been

addressed legislatively in the past. If such provisions are included in the new bill, then the status

quo is determined not only by the provisions of the previous Social Security bill, but also by the

provisions of other bills specifying the appropriate definitions, conditions etc, related to mental

health. If mental health is not included in the new bill, then the status quo should not include

provisions on mental health. In addition to the difficulties of identifying the specific policy

position of the status quo discussed in the previous paragraph, there are more serious theoretical

problems with the concept that are related to the issues of government duration, and I will

address now.

The “status quo” is an essential element of every multidimensional policy model like the

ones I have presented throughout this book. One first assumes the positions of the status quo and

the ideological preferences of different actors, and then identifies how each one of these actors

are going to behave. While the concept of “status quo” is essential in all theoretical models, little

attention has been paid into how the concept corresponds to actual political situations. Usually

312

models assume a policy space, complete information and stability of the status quo, just like all

the models I presented in the first part of this book. Such models may be sufficient when

discussing simple situations like legislation in a specific policy area. However, they are

inadequate when one discusses more complicated issues like government selection or

government survival.

I want to introduce two elements of uncertainty that will be essential in understanding the

mechanism of government selection and duration. The first element is the uncertainty between

policies and outcomes, the second is over-time uncertainty. Let me analyze each one of these

elements.

Uncertainty between policies and outcomes. Several models have assumed that there is

uncertainty between policies and outcomes (Gilligan and Krehbiel (1987), Krehbiel (1991)).

According to these models actors have preferences over outcomes, but have to select policies.

The modeling implication is that actors are located on the basis of their preferences in an

outcome space, but they cannot select outcomes directly. They have to select policies, that

include a random element in them. Only some experts have specific knowledge of the exact

correspondence between policies and outcomes, and as a result decision-makers have to extract

this information from them (I say “extract” because experts may not want to reveal it and act

strategically). However, these models do not study any further variations in outcomes; once a

policy is selected it has always the same outcomes. But this is a simplification that has been

disputed by the “events approach” to coalition formation.

Uncertainty between current and future outcomes. The “events approach” highlighted the

fact that unexpected events might challenge governments and divide the coalitions that support

them. The reason that these events are unexpected is because they are either exclusively

313

determined by happenings in the environment or jointly determined by such happenings and the

policies of governments. However, such outside events modify the position of the status quo in

the outcome space even if the policy does not change. For example, when there is an oil crisis,

the government budget (which could have been a perfect compromise at the time it was voted)

appears completely inadequate because the price of energy increases dramatically. Such

variations of outcomes (while policy remains constant) are additional sources of uncertainty. The

uncertainty between policies and outcomes was dealt with at the time of the vote of the budget,

but now the same policy produces very different outcomes than before.

Similarly, import or export policies may have different results when a trade partner

modifies some component of his behavior, or when outside conditions change. If a country is

dumping its products in the international market, or if it is exposed to say radioactivity because

of a nuclear accident, trade restrictions may become necessary, while such measures were not

even considered before.

If parties know that they are going to be confronted with both kinds of uncertainty, when

forming a government how are they are going to address the situation? First they will consider

the distance between coalition partners a very significant factor to be taken into account.

Reducing the distances between veto players enables governments to produce a policy program

before they form and respond to subsequent exogenous shocks.

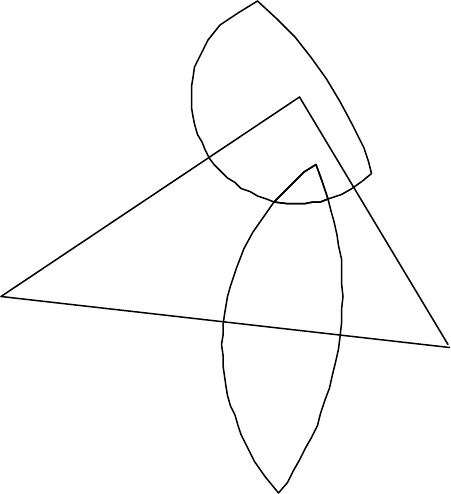

FIGURE 9.1

How would negotiations among potential veto players take place? Figure 9.1 presents an

outcome space with three potential veto players. They would discuss their government program

and include in it all the cases where the outcomes (produced by existing policies) are far away

from their preferences. For example, if the status quo was in the position SQ they would move it

314

in some point within W(SQ), and if it were at SQ1, they would move it inside W(SQ1). They

would be able to include more items in the government program the further away the status quo

is, and the closer they are to each other as we have seen in the first part of this book. In particular

Figure 1.7 and Proposition 1.4 demonstrate that what matters is not the number of veto players

but the size of their unanimity core.

Now, suppose that some exogenous shock replaces an existing outcome. The underlying

assumption in the “events approach” literature is that the size of the shock matters, and some of

them are too big for certain governments to handle. I will show that this is an inaccurate way of

thinking about the problem. In my model there are two possibilities: this movement can be

“manageable” or “non-manageable.” By manageable movement I mean a replacement of SQ that

either is very close the government program (that is, the shock in effect simulates government

policy, so no further action is necessary), or, the new SQ moves away from its previous position,

so that the government program is still included in W(SQ). In Figure 9.1 moving the status quo

from SQ1 to SQ1’ or vice versa is a manageable situation, because the coalition can respond by

leaving SQ1’ or moving back to SQ1’ as the case may be. What is of interest in this example is

that the size of the shock is not necessarily related to whether the situation is manageable. It is

possible that large shocks are easily manageable.

127

By contrast, the situation is non-manageable if the change in status quo has made an

agreement among veto players impossible. For example, if SQ is moved to SQ’ in Figure 9.1 an

agreement to go back to whatever solution was included in the government program (it had to be

within W(SQ)) is impossible. Again, non-manageable situations are not necessarily the result of

large shocks.

127

For example, if the new position of SQ is covered (see definition in Chapter 1) by the old one the situation is

manageable.

315

What are the implications of this analysis for government formation and duration? For

government formation, if there is a cluster of parties that are close to each other and they have a

majority of seats in parliament they are likely to become the government coalition. If there is no

such cluster, either a majority government will form out of parties with larger differences, or a

minority government will form. Minority government will be more likely to form when the

opposition is divided (otherwise the government could have been formed by the opposition also).

These expectations are confirmed by the empirical analysis of Martin and Stevenson (2001: 41)

who find that “any potential coalition is less likely to form the greater the ideological

incompatibility of its members, regardless of its size.” They also find that the probability of

formation of minority governments increases when the opposition is divided.

In terms of government duration Warwick has performed all the crucial tests implied by

the above analysis: he has demonstrated that the standard variables measuring parliamentary

characteristics (fractionalization and polarization of the party system) are replaced by the

ideological distances of parties in government, except for minority governments where

parliamentary polarization has a significant impact.

Finally, one additional reason why polarization of parliaments may have an independent

impact on government survival is what was discussed in Chapter 6 under the title “qualified

majority equivalents.” The existence of anti system parties essentially increases the required

majority for political decision-making form simple to qualified majority, and as a result reduces

significantly the winset of the status quo.

III. Government Stability and Executive Dominance

On the basis of the previous discussion government duration is proportional to the

government’s ability to respond to unexpected shocks, and this ability is a function of the veto

316

player constellation: on the basis of Proposition 1.4 the size of the unanimity core of the veto

players. According to my explanation there is no logical relationship between government

duration and executive dominance as argued by Arend Lijphart (1999) (see discussion in Chapter

4).

However, in Chapter 4 I only argued that government duration and executive dominance

were logically independent, and left their high correlation (the basis of Lijphart’s argument)

unexplained. Now I come back to examine the reasons of the correlation between government

duration and executive dominance. My argument is that it is a spurious correlation, and I will

explain which way the causal arrows go.

In Chapter 4 I presented evidence that executive dominance is a function of government

agenda setting powers. Indeed, while every parliamentary government has the possibility of

attaching a question of confidence to any particular bill, or, equivalently to make the

commitment that if a particular bill is defeated it will resign, this is a weapon of high political

cost and cannot be used frequently. Of more everyday use are institutional procedures that

restrict the amendments on the floor and the more of those weapons the government controls, the

more it can present the parliament with “take it or leave it” questions, and the more as a result

will it have its legislation accepted. So, Chapter 4 established a causal relationship between

government agenda setting and one of Lijphart’s variables: executive dominance.

The current chapter establishes a causal relationship between veto players and the other

variable used by Lijphart in his analysis: government duration. The argument was that the closer

the veto players, the more they are able to manage policy shocks, and consequently the longer

the duration of the government. In fact, my argument moves one step further and makes

317

predictions about government formation: the closer different potential veto players the higher

probability that they will form a government.

What needs to be established is a relation between veto player and government agenda

control. But this issue was addressed in Chapter 7. There I pointed out the strong correlation

between the two variables at the national level, and provided the reasons why this correlation is

not accidental. I was not able to establish the direction of causation but I pointed out at three

different arguments that can account for the relationship. The first was a causal argument going

from veto players to government agenda setting: multiple veto players cannot introduce

important legislation, and therefore countries with coalition governments have not been able to

introduce such agenda setting rules. The second was a strategic argument going from agenda

setting powers to veto players: if agenda setting powers are present, coalition negotiations are

easier because governments can do what they want with bare majorities or even with minorities

of votes. The third was historical, that the same sociological reasons that generated multiple veto

players also made them suspicious of each other, so that they refuse to provide agenda setting

powers to the winners of the coalition formation game. Whichever argument is empirically

corroborated, provides the direction of the causal relationship. For the time being this is an open

question. This is why in Figure 9.2 I have included an arrow pointing in both directions between

veto players and agenda setting power.

INSERT FIGURE 9.2

As this figure indicates, in different parts of the book I examined the relationships

between the different variables, and established the causal links between agenda setting and

executive dominance (Chapter 4), veto players and government duration (Chapter 9) and veto

318

players and agenda setting (Chapter 7). So, Figure 9.2 traces the origins of the correlation

between government duration and executive dominance.

Conclusions

Government formation and duration in parliamentary democracies has been a subject of

numerous studies. While the empirical literature had identified party system characteristics as the

defining variables of government duration, veto players focuses on the composition of

governments. The crucial experiments performed by Warwick demonstrate that government

characteristics, particularly the ideological distances among parties in government are better

explanatory factors of government duration than parliamentary (or party system) characteristics.

In addition, Warwick demonstrated that the ideological distances among parties in government

are better predictors of government duration than the number of parties in government, a result

that is directly presented in Figure 1.7 (and Proposition 1.4).

As a result the prediction of veto players theory that government duration is a function of

the constellation of veto players is corroborated. In addition, the distances among parties are

good predictors of government formation, which is consistent with the idea that parties are

implicitly or explicitly using reasoning consistent with veto players analysis when they

participate in the government formation process. Finally, since government duration is not an

indicator of executive dominance as I argued in Chapter 4, I explained why these two variables

had a strong correlation among them.

In the introduction to this book I referred to A. Lawrence Lowell’s (1896: 73-4) “axiom

in politics”: “the larger the number of discordant groups that form the majority the harder the

task of pleasing them all, and the more feeble and unstable the position of the cabinet.” The first

two sections of this chapter demonstrated that one hundred years later we confirm half of this

319

axiom (the part about veto players and government instability). The other half may or may not be

correct depending on the interpretation of the word “feeble.” If feeble means a cabinet that

cannot make important shifts in policy, it is exactly what the second and third parts of this book

have demonstrated. But if it means lack of “executive dominance” it is based on a spurious

correlation as the last section of this chapter indicates.

320

FIGURE 9.1

SQ

SQ’

SQ1

SQ1‘

A1

A2

A3

W (SQ)

W(SQ1)

DIFFERENT EFFECTS OF SHOCKS ON GOVERNM ENT COALITIONS

MOVEMENT FROM SQ TO SQ’ OR VICE VERSA CAN UNDO GOVERNMENT COALITION

MOVEMENT FROM SQ1 TO SQ1‘ OR VICE VERSA CAN BE HANDELED BY EXISTING VPS