Tsebelis G. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

291

open economies tend to be more sensitive to changes in tax rates than closed economies. Finally,

they also control for inflation and economic growth. From the political science literature the

possible relevant variables were: veto players (included in their analysis as a dummy variable)

and partisanship, the latter because practically all political science literature argues that right

wing parties reduce taxes for high income brackets and corporations, while the left raises taxes

with these two groups as its privileged targets.

Only two of these variables produced consistent results for both tax reductions (the

personal and the corporate one): veto players and real growth. Hallerberg and Basinger interpret

their veto player result the following way: “…The finding with regard to veto players were

extremely encouraging. A move to two or more veto players from one veto player reduces the

change in corporate rates by 18.4 points and reduces the change in the top marginal income tax

rate by 20.3 points.”

The use of a dummy variable by Hallerberg and Basinger (1998) is consistent with the

argument presented in this book. As we saw in Chapter 7 in a single dimension what matters is

the ideological distance among coalition partners. While single party governments have by

definition range of zero, the range of two or multiparty governments is not necessarily related to

the number of partners.

C. Growth and veto players. The theory I present in this book does not make any

predictions about a relationship between veto players and growth. As I said in the introduction

the underlying assumption of many economic arguments is that many veto players create the

possibility for a political system to “commit” that it will not alter the rules of the economic game,

confiscate wealth through taxation etc. Conversely, the underlying assumption of most political

analyses is that political systems should be able to respond to exogenous shocks. I have simply

292

connected the two arguments and said that high level of commitment is another way of saying

inability for political response. It is not clear whether many veto players will lead to higher or

lower growth, because they will “lock” a country to whatever policies they inherited, and it

depends whether such policies induce or inhibit growth.

Witold Henisz (2000) tested the standard economic argument, that many veto players

create a credible commitment for non interference with private property rights which “is

instrumental in obtaining the long term capital investments required for countries to experience

rapid economic growth” (Henisz 2000: 2-3).

The careful reader will recognize that this argument adds one important assumption to

my analysis: that more credibility leads to higher levels of growth. Henisz (2000: 6) recognizes

that more stability might also lock a bad status quo: “The constraints provided by these

institutional and political factors may also hamstring government efforts to respond to external

shocks and/or to correct policy mistakes… However, the assumption in the literature and in this

article is that, on average, the benefit of constraints on executive discretion outweigh the costs of

lost flexibility.”

For the empirical test Henisz (2000) creates a dataset covering 157 countries for a 35 year

period (1960-1995). He identifies five possible veto players: the executive, the legislature, a

second chamber of the legislature, the judiciary, and federalism. He constructs an index of

political constraints taking into account whether the executive controls the other veto players

(legislature, judiciary, state governments), and the fractionalization of these additional veto

players, and averages his results over five year periods. He then re-examines Barro’s analysis of

growth introducing his new independent variable. His results are that the “political constraints”

variable has additional explanatory power and its results are significant: a standard deviation

293

change in this variable produces between 17 and 31 percent of a standard deviation change in

growth.

Heinsz’s independent variable is conceptually very closely correlated with veto players,

and covers an overwhelming number of countries. However, the empirical correlation between

“political constraints” and either the number or the distances among veto players is questionable.

For example, the judiciary does not always have veto power (see Chapter 10), and federalism

seems to be double counted because it is included in the second chamber of a legislature. In

addition, legislative constraints are included while taking into account all parties in parliament.

Such an approach may be correct for presidential systems with coalitions created around specific

bills; but in parliamentary systems the government controls the legislative game (as discussed in

Chapter 4) because it is based (at least most of the time) on a stable parliamentary majority. As a

result, opposition parties impose no constraints on legislation.

These different rules of counting produce significantly different assessments of countries.

For example, Henisz finds that Canada has very high political constraints, while in this book the

classification is very different (the second chamber representing also local governments is weak

or controlled by the same party as the first, the judiciary is not so strong), while in my analysis

Canada has a single veto player. Similarly, Germany and Belgium are considered to have very

high “political constraints” while in my analyses Germany is an intermediate range of veto

players (only when the Bundesrat is controlled by the opposition is the ideological distance of

veto players high).

In sum, the big advantage of Henisz dataset is that it covers the highest number of

countries reported in this book; the disadvantages are that some constraints are introduced

without reflecting the actual decision-making process, and that while a plausible mechanism

294

(according to which constraints affect credibility of commitments, affect investment, affect

growth) is identified only the first and last step of the process are shown to be correlated.

IV CONCLUSIONS

This chapter discussed empirical studies of a series of macroeconomic outcomes. All of

them seem to be correlated to the structure of veto players in an important way: the more veto

players and/or the more distant they are, the more difficult is the departure from the status quo.

Indeed, budget deficits are reduced at a slower pace (when their reduction becomes an important

political priority), the structure of budgets becomes more viscous, inflation remains at the same

levels (whether high or low), tax policies do not change easily. All these results indicate high

stability of outcomes. In addition, reviewing the literature, we encountered the empirical

corroboration of an outcome expected in the economic literature: the existence of many veto

players may reduce the political risks associated with an active government, increase investment,

and lead to higher levels of growth.

Most of the analyses discussed in this chapter use either some measure correlated to veto

players (like Treisman’s (2000c) federalism, Hallerberg and Basinger’s (1998) veto dummy) or a

one dimensional indicator (Bawn (1998), Franzese (1999)). One study however, Tsebelis and

Chang (2002) makes use of the multidimensional analysis presented in the first part of this book

and produces results that are significantly better than one-dimensional analyses (whether of the

first or of the second axis).

295

TABLE 8.1

Estimated Results on Budget Structure in 19 OECD Countries, 1973-1995

(simple model estimated by multiplicative heteroskedastic regression).

MODEL 1 MODEL 2

Dependent Variable: The Expected Value of Budget Distance

Constant .2746***

(.0198)

.2820***

(.0201)

Lagged BD .1503***

(.0349)

.1360***

(.0351)

Ideol. Distance -.0189

(.0168)

Dependent Variable: The Error Term of Budget Distance

Constant -2.5671***

(.0776)

-2.524***

(.0769)

Ideol. Distance -.2087***

(.0883)

N 338 338

Prob >

2

?

0.000 0.000

Likelihood-ratio test between Model 1 and Model 2:

2

2

? = 5.96 Probability >

2

2

? = 0.050

Note: Standard errors in parenthesis.

* significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%, all tests are one-tailed.

296

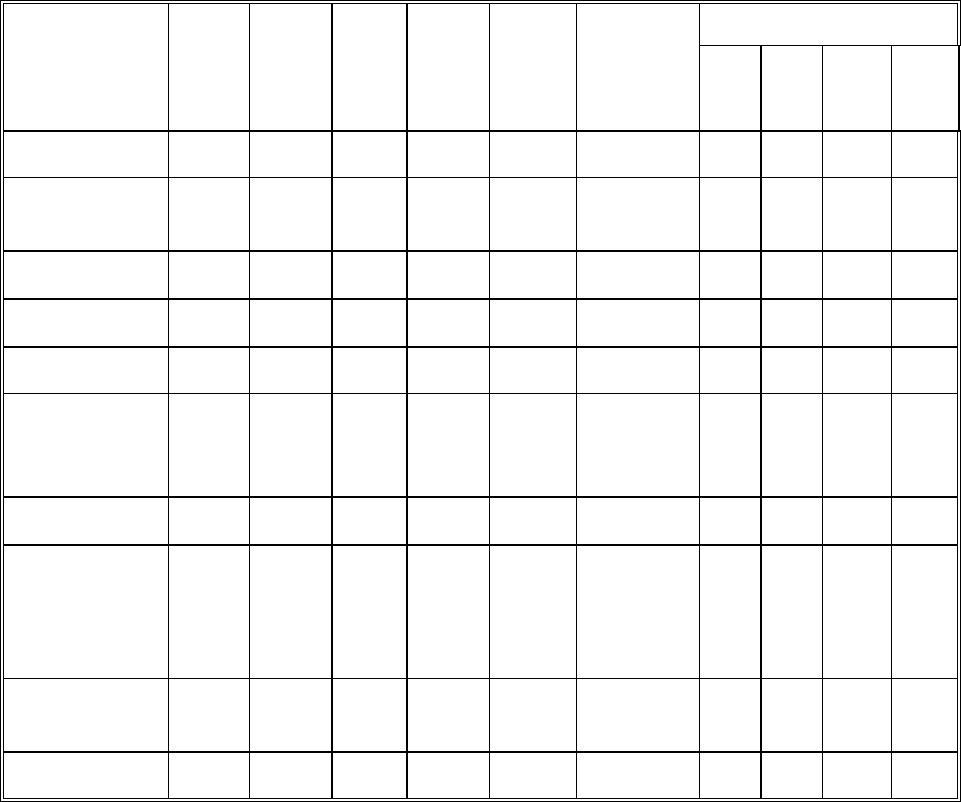

TABLE 8.2

Estimated Results on Budget Structure in 19 OECD Countries, 1973-1995 (Complete

Model Estimated by Fixed-Effect Cross-Sectional Time-Series Model with Panel

Correction Standard Errors).

MODEL 1

Coefficient

MODEL 1 Stand.

Coefficient

MODEL 2

Lagged BD 0.0588 (0.0483) 0.0890 (0.0731) 0.0628 (0.0474)*

Ideol. Distance -0.0615 (0.0277)** -0.1838 (0.0828)** -0.0620 (0.0278)**

Alternation 0.0472 (0.0158)*** 0.1755 (0.0587)*** 0.0477 (0.0158)***

?unemployment 0.0304 (0.0204)* 0.0849 (0.0570)* 0.0307 (0.0204)*

?age>65 0.0227 (0.1360) 0.0101 (0.0605)

?GROWTH 0.0018 (0.0042) 0.0261 (0.0609)

?INF 0.0060 (0.0067) 0.0416 (0.0465)

Australia 0.1474 (0.0518)*** 0.1652 (0.0447)***

Austria 0.1048 (0.0381)*** 0.1213 (0.0280)***

Belgium 0.2615 (0.0884)*** 0.2871 (0.0838)***

Canada 0.1694 (0.0509)*** 0.1876 (0.0429)***

Denmark 0.2783 (0.0514)*** 0.2934 (0.0473)***

Finland 0.2906 (0.0764)*** 0.3085 (0.0710)***

France 0.2053 (0.0971)** 0.2151 (0.0929)**

German 0.1345 (0.0509)*** 0.1505 (0.0374)***

Iceland 0.3863 (0.0833)*** 0.4236 (0.0700)***

Ireland 0.1656 (0.0460)*** 0.1794 (0.0440)***

Italy 0.4881 (0.0904)*** 0.5102 (0.0807)***

Luxembourg 0.2710 (0.0391)*** 0.2932 (0.0303)***

Netherlands 0.2109 (0.0738)*** 0.2239 (0.0698)***

New Zealand 0.2540 (0.0643)*** 0.2814 (0.0557)***

Norway 0.1519 (0.1104)* 0.1652 (0.1092)*

Portugal 0.5030 (0.1032)*** 0.5315 (0.0975)***

Spain 0.4638 (0.1912)*** 0.4751 (0.1883)***

Sweden 0.2515 (0.0607)*** 0.2731 (0.0512)***

UK 0.1397 (0.0602)*** 0.1572 (0.0566)***

N 336 336 336

R

2

65.32% 65.32% 65.21%

Prob >

2

?

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

* significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%, all tests are one-tailed.

297

TABLE 8.3

Estimated Results for Each Budget Category

BUDGET CATEGORY IDEOLOGICAL

DISTANCE

ALTERNATION

General Public Services -.0895 (.0526)** .0118 (.0334)

Defense -.0157 (.0245) .0176 (.0136)*

Education -.1242 (.0735)** .0433 (.0320)*

Health -.2550 (.1076)***

.1566 (.0584)***

Social Security and Welfare -.2915 (.1082)***

.0965 (.0724)*

Housing and Community Amenities .0224 (.0468) -.0193 (.0399)

Other Community and Social Services -.0125 (.0130) .0044 (.0060)

Economic Services -.1574 (.1301)* .0602 (.0528)

Others -.2156 (.1728)* .0883 (.1014)

Note: Estimated coefficients for country dummies, change in unemployment

rate and lagged dependent variable are surpassed to facilitate the presentation.

Panel-correction standard errors are in parentheses. * p<0.1, ** p<0.05,

*** p<0.01; all tests are one-tailed.

298

TABLE 8.4

Comparison of Explanatory Power of Single-Dimensional analysis and Two-Dimensional

analysis.

Improvement

Budget

I. D.

in 1

st

Dim.

Alt.

in 1

st

Dim.

I. D.

in 2

nd

Dim

Alt. in

2

nd

Dim.

I D. in

Two-

Dim.

Alt. in

Two-Dim.

ID

1

st

? 2

Alt

1

st

? 2

ID

2

nd

? 2

Alt

2

nd

? 2

Total ** C ** *** ** ***

?

General Public

Services

**

W

C W **

C

? ? ?

Defense

C * C C C *

?

Education

** W C C ** *

? ? ?

Health

*** ** ** *** *** ***

? ?

Social

Security and

Welfare

** *** *** * *** *

? ?

Housing

C * W W W W

? ?

Other

Community

and Social

Services

** W C W C C

? ?

?

Economic

Services

* W C C * C

? ?

Others

C W * C * C

? ?

Note:* denotes the level of significance: * p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. C denotes “correct

sign”, W denotes “wrong sign”, ? denotes improving results whereas ? denotes worsening

results.

299

PART IV: SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF VETO PLAYERS

In this last part we discuss the structural outcomes of policy stability. Why should we

care if it is easy or difficult to change the status quo? As we said in the introduction, one way of

conceiving policy stability is like a credible commitment of the political system not to interfere

in economic, political, or social interactions and regulate them. Another way is to conceive

policy stability as the inability of the political system to respond to changes occurring in the

economic, political or social environment. Both these aspects are intrinsically linked, and

inseparable. Some analysts may prefer one way of thinking to the other, until the moment that

institutional structure praised for its ability to make credible commitments is unable to respond to

some shock, or the political system with admirable decisiveness was not able to make credible

commitments. The argument so far, was that particular institutional structures will produce

specific levels of policy stability, and it is not possible to have credibility some of the time and

switch to decisiveness when you need it. Deciding an institutional structure locks the situation to

a certain level of policy stability. But what are the results of different levels of policy stability?

Policy stability has multiple effects. First, in presidential regimes if policy stability is

high regime instability increases (as we saw in Chapter 3): it is possible for the president or the

military to turn against the democratic institutions that are unable to solve the problems of the

country. In the three chapters of this part we will examine more in detail other results of policy

stability.

The first result of policy stability that we will study in Chapter 9 is government instability

in parliamentary democracies. As we saw parliamentary systems have the flexibility of

government change when there is a political impass. The government decides to challenge

parliament with a question of confidence and loses, or resigns because it cannot pass its

300

legislation through parliament, or the parliament that disagrees with the government removes it

from power. A significant disagreement between government and parliament leads to a new

government coalition that may (or may not) resolve the political impass. What is interesting in

this story is that what is perceived as “political impass” by the players is what we have called

policy stability throughout this book. Consequently, policy stability increases the probability of

replacing governments, or as we will say from now on government instability.

Chapter 9 addresses the question of government survival. While most of theoretical and

empirical analyses explain government instability by characteristics prevailing in the parliament

of a country, veto players focuses on the composition of governments to explain government

survival. As has been demonstrated in the work of Warwick (1994) explanations based on

government composition are more accurate empirically. What this chapter will show is that this

analysis is consistent with the veto players framework introduced in this book. I will show that

the veto players theory combined with a theoretically informed understanding of the concept of

“status quo” can account for all the puzzling findings of the empirical literature.

Chapter 10 deals with the independence of bureaucracies and the judiciary. I explain why

policy stability leads to higher independence of these two branches, and present empirical

evidence corroborating the expecations. I compare my findings for both bureaucrats and judges

with other theoretical or empirical work. If different theories generate different expectations, I

explain the reasons for the differences as well as look to the empirical evidence for

corroboration.

Chapter 11 applies the veto players theory to an unusual case: the European Union (EU).

According to Alberta Sbragia (1992: 257) the EU is "unique in its institutional structure, ...

neither a state nor an international organization." The EU has also changed its constitution