Tsebelis G. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

131

no matter whether this second chamber is the House or the Senate. Legislation that is approved

by the system A of veto players will necessarily have the approval of the system B. Similarly, if

a country had a bicameral legislature with one chamber composed only of the veto players in

system A, and the other composed of the system of As and one B the overall situation would be

equivalent with a single cameral legislature composed out of the three veto players of the system

A. For example, in Japan the leading LDP lost the majority in the Senate in 1999. As a result the

LDP included representatives of the Liberals and Komeito (Clean Government Party) in the

government, although technically speaking their votes were not required for a House majority.

Similarly in Germany if the Bundesrat is controlled by the opposition the situation is not

politically different from a grand coalition: legislation that is not approved by both major parties

will not be accepted. Or, in a Presidential system if the president’s party has the same

preferences with the president it will be part of any policymaking coalition, because if a bill does

not get its support it will be vetoed by the President. So, the current version of the absorption rule

is much more general from the one criticized by Strom and takes into account some of his

objections.

It is also true that parties members of oversized governments can be bypassed as veto

players, while institutional veto players cannot as Strom argues. I deal with this objection

theoretically in Chapter 4 and present empirical evidence supporting my argument in Chapter 7.

Where Strom is not correct in my opinion is in the last part of his argument where he

proposes, “The same treatment [i.e. absorption] should be accorded to partisan players that have

no demonstrable opportunity to exercise veto.” Parties in government are there to agree on a

government program. In fact, as we will see in the next chapter such programs take a long time

to be negotiated, governments make serious efforts to have voted and implemented everything

132

included in them as de Winter (2001) has carefully demonstrated. In addition, if new issues come

on the political horizon the different parties members of government have to address them in

common. If such a political plan is not feasible the government coalition will dissolve, and a new

government will be formed. So, the request that parties in government have “demonstrable

opportunity to exercise veto” is either equivalent to participation in government, or unreasonable.

Indeed, participation in a government grants parties the right to veto legislation and to provoke a

government crisis if they so wish. This is a sufficient condition for a party to qualify as veto

player. If “demonstrable opportunity” is on a case by case basis, it is impossible to be met

empirically, because even cases where veto was actually exercised and legislation was aborted as

a result may not be “demonstrable” given the secrecy of government deliberations.

Another type of criticism is empirically based. The argument is that in some specific

issue different kinds of veto players have conflicting effects, so, veto players should not be

included in the same framework. Here is how Vicki Birchfield and Markus Crepaz present the

argument: “Not all veto points are created equal. We argue that … it is necessary to distinguish

between “competitive” and “collective veto points” which are not only institutionally different

but also lead to substantively different outcomes. Competitive veto points occur when different

political actors operate through separate institutions with mutual veto powers, such as federalism,

strong bicameralism, and presidential government. These institutions, based on their mutual veto

powers, have a tremendous capacity to restrain government…. Collective veto points, on the

other hand, emerge from institutions where the different political actors operate in the same body

and whose members interact with each other on a face-to-face basis. Typical examples of

collective veto points are proportional electoral systems, multi-party legislatures, multi-party

133

governments, and parliamentary regimes. These are veto points that entail collective agency and

shared responsibility.” (Birchfield and Crepaz (1998: 181-82)).

These arguments seem similar to Strom’s in the sense that they are intended to

differentiate presidential from parliamentary systems, but significantly less precise. For example,

the “face to face basis” does not distinguish the interaction between government and parliament

on the one hand and conference committees in bicameral legislatures on the other. In both cases

there is personal interaction but not very frequent, so it is not clear why parliamentarism is

distinguished form bicameralism on this basis.

On the basis of outcomes, the authors argue that higher economic inequality associated

with competitive veto players, and lower associated with collective ones. In another article

Crepaz (2001) finds similar results associated with Lijphart’s (1999) first and second dimension

of consociationalism, the “executive-parties dimension” and the “federal-unitary dimension.” In

the same article Crepaz (2001) equates the two distinctions: Lijphart’s first dimension with the

Birchfield and Crepaz “collective veto points” and Lijphart’s second dimension with the

Birchfield and Crepaz “competitive veto points.”

I find some inconsistencies in these arguments and I consider the generalizability of their

findings questionable. Lijphart’s distinctions are not equivalent with those made by Birchfield

and Crepaz. For example, the former includes the following five characteristics in his federal-

unitary dimension: 1) unitary vs. federal government. 2) unicameral vs. bicameral legislatures. 3)

flexible vs. inflexible constitutions. 4) absence or presence of judicial review. 5) central bank

dependence or independence. There is no reference to presidential government, which Birchfield

and Crepaz consider a characteristic of “competitive veto players”, and there is no reference of

central banks, or constitutions, or judicial review in the competitive veto players concept of

134

Birchfield and Crepaz. Similarly, parliamentarism is a characteristic of collective veto players

according to Birchfield and Crepaz, but not a characteristic of Lijphart’s first dimension;

corporatism is a characteristic for Lijphart, but not for Birchfield and Crepaz. As a result of these

differences, I am not sure which characteristics are responsible for the inequality results.

If one eliminates the characteristics that are not common in the different indexes (which

would include presidentialism vs. parliamentarism, which is not in Lijphart’s list) the common

denominator of the findings is that federalism increases inequalities but multipartyism reduces

them. I can understand why federalism is likely to increase inequalities: because some transfer

payments are restricted within states, consequently, if the federation includes rich and poor states

transfers from the former to the latter are reduced compared to a unitary state. I do not know why

multiparty governments reduce inequality, and I do not know whether this finding would

replicate in samples larger than OECD countries. If there is a connection, in my opinion, it

should incorporate the preferences of different governments. It is not clear that all governments

try to reduce inequalities, so that multiparty governments are “enabled” (as Crepaz claims) to do

so more than single party ones. The usual argument in the literature is that the Left (as a single

party government or as a coalition) aims at reducing inequalities, not some particular institutional

structure.

Finally, even if there are answers to all these questions, the relationship between

inequality and specific institutional characteristics is not a negation of the arguments presented in

this book. Nowhere have I argued that veto players produce or reduce inequalities. In addition,

this chapter argues that while there may be similarities among non-democratic, presidential and

parliamentary regimes with respect to the number of veto players and the ideological distances

among them, there are differences in terms of agenda setting and party cohesion. Nor have I ever

135

argued that federalism has no independent effect besides the one operating through veto players.

As I will demonstrate in Chapter 6, federalism is correlated with veto players because it may add

one or more veto players through the strong second chamber of a federal country, or through

qualified majority decisions. As a result, federalism can be used as a proxy of veto players when

information on veto players is not available.

59

However, this is not the only possible effect of

federalism and it may also operate independently. For example, in Chapter 10 I argue that federal

countries are more likely to have active judiciary because these institutions will resolve problems

of conflict between levels of government.

In conclusion, Strom has helped identify some weaknesses in earlier versions of my

argument. The expansion of the absorption rule introduced in this book covers both institutional

and partisan veto players. Strom has a valid argument with respect to non-minimum winning

coalitions, which I will address in the next chapter. But he introduces too severe a restriction in

parliamentary systems when he requires that “demonstrable opportunity to exercise veto” should

be present for a party to count as a veto player. I argue that participation in government is a

sufficient condition.

Conclusions

I presented a review of the differences between non-democratic and democratic systems,

as well as between presidential and parliamentary systems, and re-examined these literatures on

the basis of veto players theory. This analysis led me to introduce the concepts of institutional

and partisan veto players, and to identify such players in a series of situations. It turns out that

the number of veto players may change over time in a country (if some of them are absorbed

because they modify their positions), or that the same country may have different veto player

constellations depending on the subject matter of legislation (like Germany).

59

In chapter 10 I discuss an article by Treisman (2000) using exactly this strategy.

136

With respect to veto players, while non-democratic regimes are generally considered to

be single veto player regimes, close analysis may reveal the existence of multiple veto players.

So, the number of veto players is not a fundamental difference between democratic and non-

democratic regimes either.

My review of the literature on presidentialism and parliamentarism pointed out that while

there is a conclusive difference in terms of the probability of survival of democracy, all other

differences are disputed in current political analysis. Analysis of presidentialism and

parliamentarism points out that the most important difference between these regimes is the

interaction between legislative and executive in parliamentary systems and their independence in

presidential ones. The other differences seem fuzzy. In terms of veto players there are similarities

between presidential and multiparty parliamentary systems, and they contrast with single party

governments in parliamentary systems. There are differences between presidential and

parliamentary systems in terms of who controls the agenda governments in parliamentary

systems, parliaments in presidential ones (to be discussed further in the next chapter), and in

terms of the cohesion of parties in each system (presidentialism is on the average associated with

lower cohesion). We will focus on the question of who controls the agenda and how in the next

chapter.

137

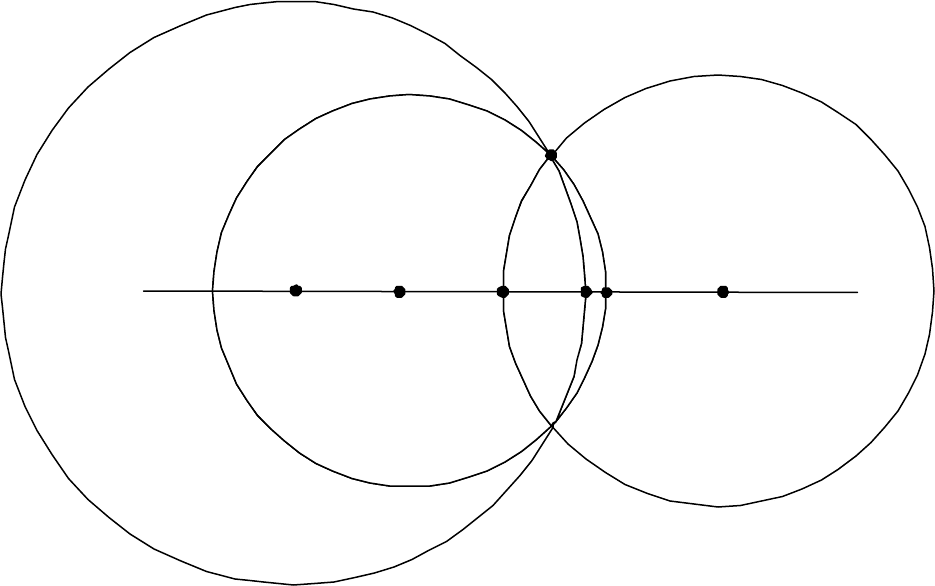

Difference between “Gore” and“Bush” presidency

when the president controls or does not control the agenda

TD

GB

AG

PAG

PGBPP

FIGURE 3.1

SQ

Both Presidents make the same proposal (PP) if they control theagenda;

If theagenda is controlled bythe legislative “Gore” accepts PAG, and “Bush” PGB

138

CHAPTER 4: GOVERNMENTS AND PARLIAMENTS

Introduction

In this chapter I focus on agenda setting mechanisms more in detail. I demonstrate that

there are two important variables one has to examine in order to understand the power of the

government as an agenda setter in parliamentary systems. The first is positional, the relationship

between the ideological position of the government and the rest of the parties in parliament. The

second is the institutional provisions enabling the government to introduce its legislative

proposals and have them voted on the floor of the parliament, that is, the rules of agenda setting.

Both these questions are generated from the analysis in Part I. They focus on agenda setting and

study the positional and institutional conditions for it. It turns out that my analysis has some

signficnat differences from the existing literature.

The first difference is that we will be focusing on the characteristics of governments in

parliamentary systems instead of the traditional party system focus (Duverger, Sartori).

According to the traditional literature two party systems generate single party governments

where the parliament is reduced into a rubberstamp of government’s activities, while multiparty

systems generate more influential parliaments. The party systems analysis focuses on

parliaments because they are the source from where governments originate, in technical terms

the “principals” who select their “agents”. Veto players focuses on governments because they are

the agenda setters of legislation as we said in Chapter 3. Single party governments will have all

discretion in changing the status quo, while multiparty governments will make only incremental

changes.

A second difference between my analysis and existing influential literature is the question

of exclusive ministerial jurisdictions (Laver ans Shepsle (1996)). On the basis of my analysis

agenda setting belongs to the government as a whole. It is possible that in some areas it is the

139

prime minister, in others the minister of finance, in yet others the corresponding minister. It can

also done through bargaining among the different government parties. All these possibilities are

consistent with my approach, while Laver and Shepsle assign agenda setting to the

corresponding minster.

A third difference regards the interactions between governments and parliaments. While

most of the literature differentiates between presidential and parliamentary regimes, one

researcher (Lijphart (1999)) in his influential analysis of consociational versus majoritarian

democracies merges regime types (like this book does) and focuses on the concept of “executive

dominance” as a significant difference between and across regimes. Executive dominance in

Lijphart’s words captures “the relative power of the executive and legislative branches of

government” (Lijphart (1999: 129)) and is approximated by cabinet durability in parliamentary

systems. I argue that the interaction between executives and legislatures is regulated by an

institutional variable: the rules of agenda setting. Let me explain what these differences involve.

The difference of an analysis on the basis of party systems (i.e. parties in parliament) or

government coalitions (i.e. parties in government) may appear to be trivial. After all, multiparty

systems lead usually to coalition governments, and two party systems to single party

governments. However, the correlation is not perfect. For example, Greece (a multiparty

country) has a government that completely controls the legislature. Besides the differences in

empirical expetations (Greek governments are expected to be strong on the basis of veto players,

while their single party composition is a failure of understanding the relationship between

governments and parliaments generated by party system analysis) the major difference is in the

identification of causal mechanisms shaping the interaction between governments and

parliaments.

140

I also argue that the veto players variable is not dependent on institutions or party

systems alone, but derived from of both of them. For example, veto players include not only

partners in government, but also second chambers of the legislature, or presidents of the republic

(if they have veto power). In addition, a party may be significant in parliament and count in the

party system of a country, but its approval of a legislative measure may not be required in which

case it will not be a veto player. Finally, one or more veto players whether a government partner,

a second chamber, or a president of the republic may be absorbed and not count as veto players

as demonstrated in Chapter 1.

The question whether it is minsters that control the agenda or the whole government is a

minor one, however since my approach shares Laver and Shepsle the importance attributed to

agenda setting, I need to clarify that some empirical evidence conflicting with their expectations

does not affect my analysis.

Equally trivial may seem the difference on whether the relationship between governments

and parliaments is determined on the basis of government duration or agenda setting rules. Yet,

government duration varies only in parliamentary systems, ans consequently cannot be used as a

proxy of executive domiance in presidential systems, or across systems; agenda setting rules can

be used across systems. In addition, I argue that there is no logical relationship between

executive dominance and government duration, so a different variable is necessary for the study

of the relationship between legislative and executive. I demonstrate that this relationship can be

capured by the rules regulating legislative agenda setting.

The chapter is organized in three sections. Section I studies the positional conditions of

agenda setting. I focus on different kinds of parliamentary governments (minimum winning

coalitions, oversized governments and minority governments) and study their ability to impose