Tony Dorcey - Large dam

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

Appendix B 131

opment with the environment. And at the core of this

challenge lies energy—the fuel of economic develop-

ment from time immemorial.

Who says energy says carbon. And carbon is now

the “most wanted” environmental culprit. Conversely,

displacement of carbon for the energy system may be

the largest single environmental challenge facing the

planet. Progress has been slow but sustained over

the past century. Since 1860, decarbonization has cut

the tons of carbon to units of energy produced by 40

percent. In 1920, coal still provided three-quarters of

global energy, and heavy smog lay over London and

Pittsburgh. Today, carbon is struggling to sustain its

market share of about 25 percent. The move from a

polluting carbon economy to a non-polluting hydro-

gen economy is underway. It will have to be acceler-

ated to keep global warming at bay.

Dams have a significant role to play in freeing the

energy system from carbon. When built on time and

on budget, they produce electric power at competitive

prices. Electricity can substitute for wood, coal,

kerosene and oil and therefore contribute to a clean-

er, safer, healthier environment.

With electricity, deadly wastes associated with

open fire and smoke in homes and workplaces

decline and with it exposure to pneumonia, TB, diph-

theria and other airborne diseases. Refrigeration also

becomes possible, and this cuts into waterborne gas-

trointestinal diseases—another major killer.

Electricity used to be based on coal alone. Hydro

is a viable alternative in certain situations. So is nat-

ural gas, which has increased its market share given

its flexibility, quick gestation, low capital costs and

the efficiency of combined cycle turbines. Natural

gas is carbon trim—four hydrogens for every carbon.

Coal uses one to two carbons per hydrogen. Oil uses

two hydrogens per carbon, while wood uses ten car-

bons per hydrogen. So only nuclear and hydro can

beat natural gas in the decarbonization game. But

nuclear involves high risks and heavy costs, while

hydro lies well within the technological reach of most

developing countries.

Hydro is renewable and domestic-resource-based.

By contrast, fossil fuels often require foreign

exchange. Furthermore, hydro projects are easy to

operate and maintain. No wonder then that two-

thirds of the large dams built in the 1980s were in

developing countries. The power market in develop-

ing countries is growing, and this is where the bulk

of unexploited sites lies. According to the World

Energy Council, a doubling of energy production for

hydro from 2,000 terawatt hours to 4,000 terawatt

hours per year from 1990 to 2020 is in store. This

implies a trebling of hydro capacity and, if it occurs,

would still leave 70 percent of the technically usable

potential untapped.

Such a development would contribute substantially

to reduced reliance on carbon as well as bring down

the currently high energy intensities of the develop-

ing world. Measured in tons of oil, for example per

U.S. dollar of GDP, Thailand resembles the United

States in the 1940s, while India is comparable to the

United States of a century ago. Keeping energy use

at current levels in developing countries is an envi-

ronmental fantasy that would confine them to perpet-

ual poverty. Per capita, LDC residents use only

1/15th of the energy consumed by a U.S. resident.

I will not talk about the extraordinarily important

use of dams for irrigation. But consider this simple

fact. By raising wheat yields fivefold during the past

few decades, Indian farmers have spared an area of

cropland equal to the state of California. This yield

revolution would not have taken place without sur-

face irrigation used in conjunction with ground water.

So there is a strong economic and environmental

case for large dams. But as dams are currently

designed, constructed and implemented, a strong

case can also be made against them. The damming

of a river can be a cataclysmic event in the life of a

riverine ecosystem. The construction of dams in

densely populated, environmentally sensitive, institu-

tionally weak areas can be very destructive.

Just as in real estate, location matters.

Consultation matters too. But it is not a panacea.

The protection of natural habitats and the resettle-

ment of people displaced by dams call for institutions

and implementation capacities that need nurturing

over many years, even decades. These are not chal-

lenges that can be met efficiently one project at a

time. The OED report suggests that 75 percent of

the dams reviewed did not meet current environmen-

tal/resettlement standards at completion and hypoth-

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:47 PM Page 139

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

132 Appendix B

esizes that had they done so they would still have

yielded an attractive rate of return. The Bank has

now changed its policies, but compliance with them

remains a massive challenge. It cannot be achieved

through conditionality and paper plans. It requires

country commitment, appropriate domestic legisla-

tion and adequate enforcement and implementation

capacity. The constraint is not engineering hardware.

It is the societal software, the rules of economic and

social governance and the ability of local agencies to

get things done. These institutional building tasks

should lie on the critical path of dam construction

programs.

This is where today’s workshop comes in. It is

part of an unfolding change process that is taking

place globally as well as locally. Technologically, imi-

tation, adaptation and sharing of experience has

improved the ways dams are built. In particular, safe-

ty standards are now better understood and dissemi-

nated. The time has now come to promote a similar

change process with respect to the human and eco-

logical dimensions of large dams projects. Fact-find-

ing is more effective than fault-finding. No society

should be excluded from learning. Latecomers

should be able to benefit from the costly experiments

of pioneers. This is the challenge of evaluation and

also of this workshop.

I put the idea of workshop to George Greene a few

months ago and, with the support of the Bank’s man-

agement and its Board, and a similar process within

IUCN, we have moved forward. The “going” will

undoubtedly get tough, but this a tough group and I

am confident that it will get going.

Our joint approach to the workshop is straightfor-

ward. We have brought together leading representa-

tives of major stakeholders in a neutral setting. We

would have loved to have even broader consultations.

But with a larger group, we would not have had the

opportunity to get acquainted and listen in detail to

each other’s point of view. Broader consultation will

be needed in future—that is for the workshop to dis-

cuss.

So, let’s reason together and decide which are the

most important issues that need to be addressed.

The Phase I report identifies a few key issues and

proposes specific areas for follow-up. We have also

been privileged to have leading authorities prepare

and present excellent overview papers covering eco-

nomic/engineering, social and environmental issues.

You will undoubtedly have many more ideas and pro-

posals of your own, which you will have an opportuni-

ty to air and discuss in the working groups this after-

noon and tomorrow morning.

There is not shortage of issues. They key is to

identify those that are so critical that they deserve

the scarce resources that we’ll have at our disposal.

Basically, we don’t want to go back home with a long

list of additional problems. We are here to put in

place a framework and a process that will eventually

get them solved. Once we select the priority ones, let

us start on the next steps.

Methodology is certainly an issue. In the Phase I

report, we used a cost/benefit framework. It forces

everything onto a common denominator, and leads to

a bottom line. It can be used to compare large dams

with alternatives, and with any other application of

the scarce human, natural and financial resources

that a proposed project requires.

But the cost/benefit approach has its limitations.

We are open-minded about other evaluative frame-

works that promise a better integration of issues

and/or a more acceptable comparison with alterna-

tives given the objective of sustainable development.

We need to be concerned about the acceptance of

whatever emerges from this workshop by the broad-

er community. I am talking about potential investors,

governments, affected communities, beneficiaries

and others who have a stake in the future of large

dams—particularly those that are involved in the 98

percent of the dams that are not financed by the

World Bank. This is the challenge for the next

phase. And it has implications for the way Phase II is

conceived.

We need a rigorous, professional and transparent

process for defining the scope, objectives, organiza-

tion and financing of follow-up work. We need to

develop basic guidelines for involvement by govern-

ments, the private sector and NGOs, as well as broad-

er community and public participation, information

disclosure and subsequent dissemination of results.

We should not emerge from this workshop only with

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:47 PM Page 140

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

Appendix B 133

a warm feeling and a somewhat better understanding

of each other’s concerns. Our time together is too

short to get into in-depth discussions of specific

issues and cases. Perhaps we ought to focus on prin-

ciples, processes and partnerships that will help

address the critical issues in a manner that will find

general acceptance.

Developing partnerships should be a key element

for reaching out to the world of stakeholders outside

this room. I don’t think OED can or should handle

Phase II on its own, and neither should the Bank. We

are prepared to remain involved, but we don’t need to

be at the center, at the top, or in the most prominent

seat. What is important to us is that the issues be

effectively addressed; i.e., that the follow-up actions

gradually lead to standards for the assessment, plan-

ning, building, operation and financing of large dams

that are generally accepted by the governments and

the peoples of the developing world as well as the

external agencies, whether public, private or volun-

tary, with a stake in the development process.

So the challenge before all participants today and

tomorrow is to invent a plan of action that will trigger

real change. Generally accepted standards and best

practice examples should be sought so as to get

results on the ground. Equally, new ways of coopera-

tion must replace the current gridlock of distrust and

recrimination. Governments of developed and devel-

oping countries will have to be involved far more

actively than they have been so far. The private sec-

tor will also have to be associated with the next steps.

If ways are not found out of the current logjam, dams

will continue to be built, but they will be built at a

slower rate with great pain and at a higher human

and environmental cost than necessary. If, on the

other hand, the workshop succeeds, a win/win logic

may eventually take over and the history of dam con-

struction will evolve from confrontation to coopera-

tion for the benefit of all. So let us try to make histo-

ry today.

April 9, 1997

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:47 PM Page 141

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

134 Appendix B

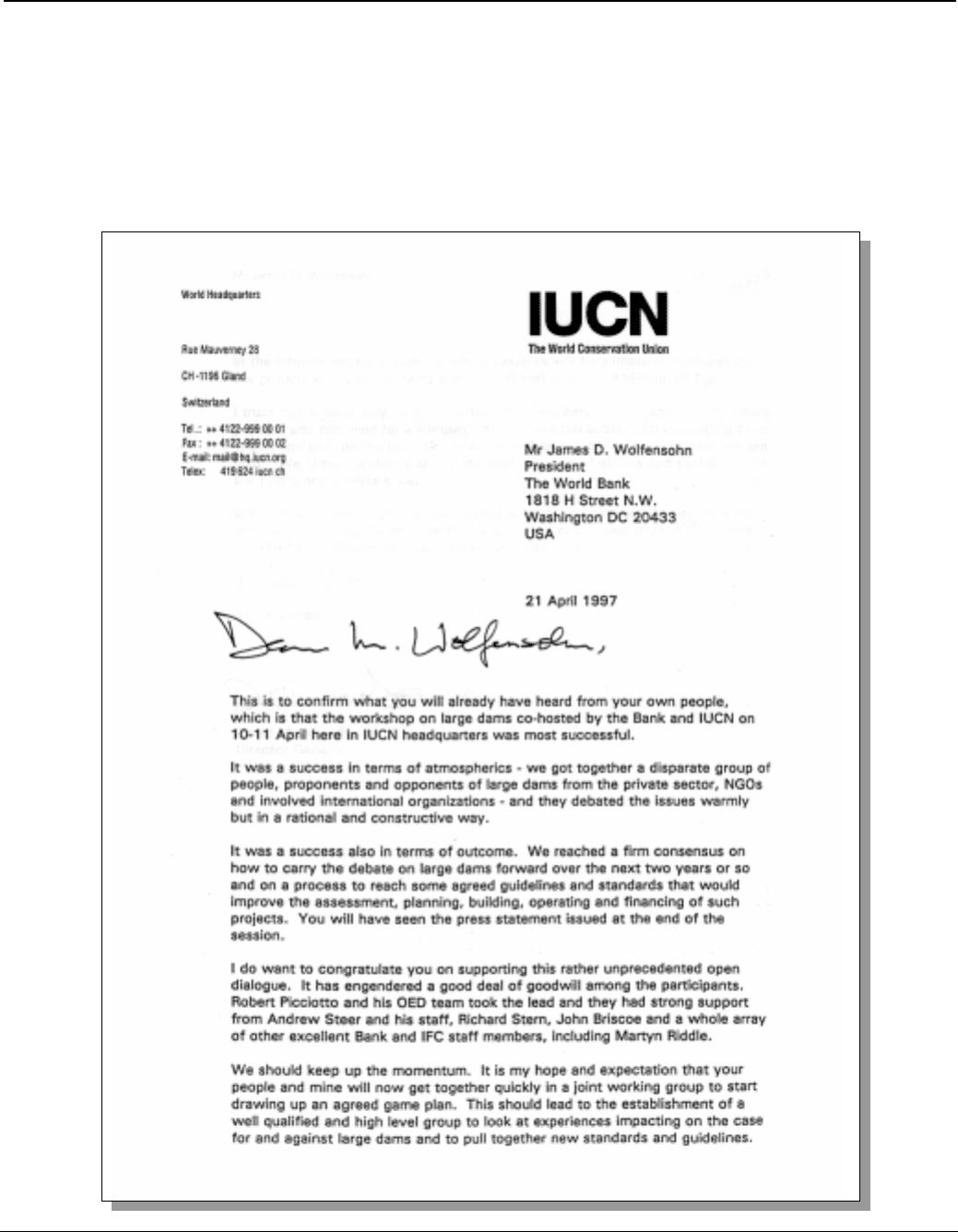

APPENDIX B3:

POST-WORKSHOP CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN:

IUCN Director General World Bank President

DAVID McDOWELL JAMES D. WOLFENSOHN

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:47 PM Page 142

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

Appendix B 135

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:47 PM Page 143

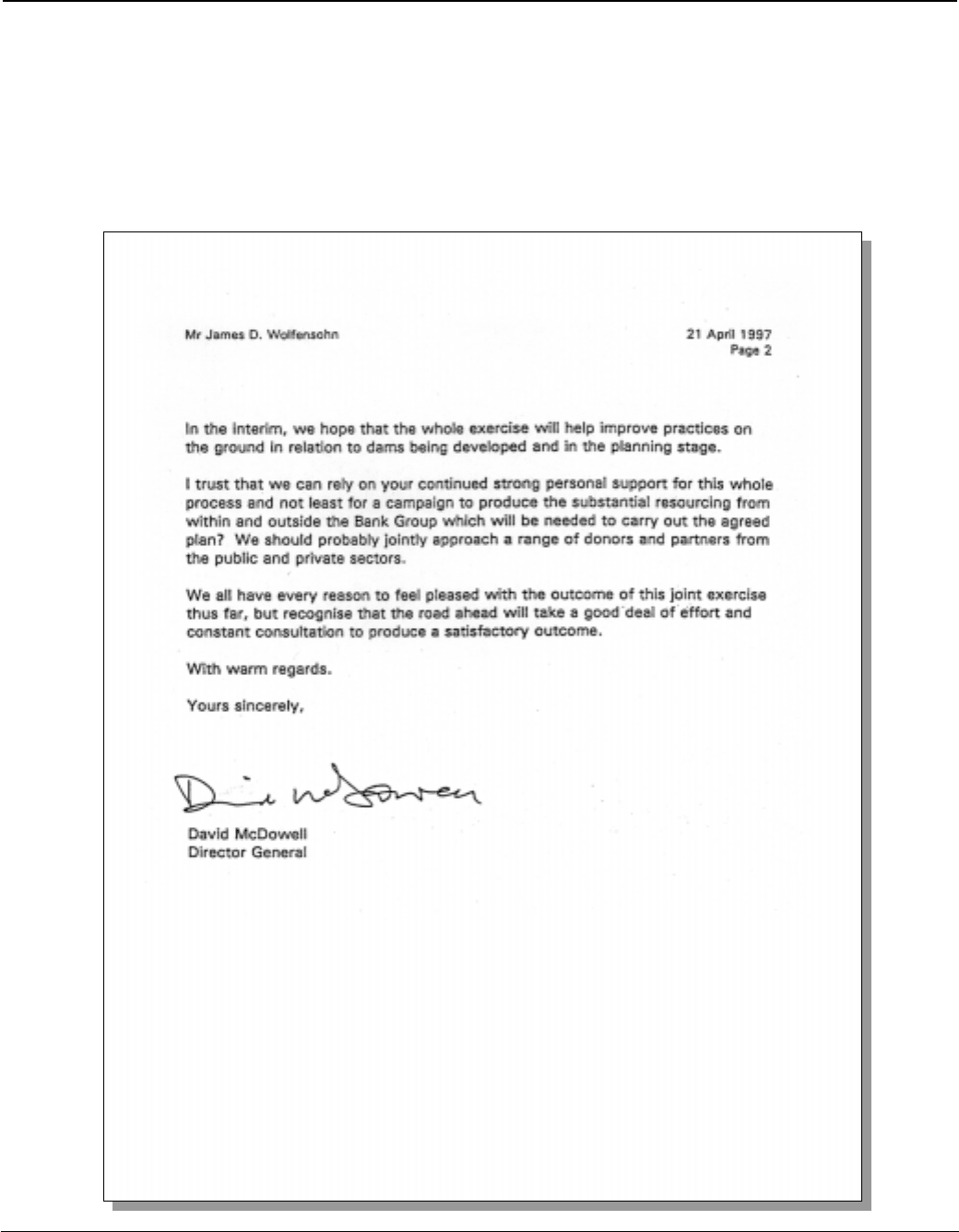

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

136 Appendix B

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:48 PM Page 144

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

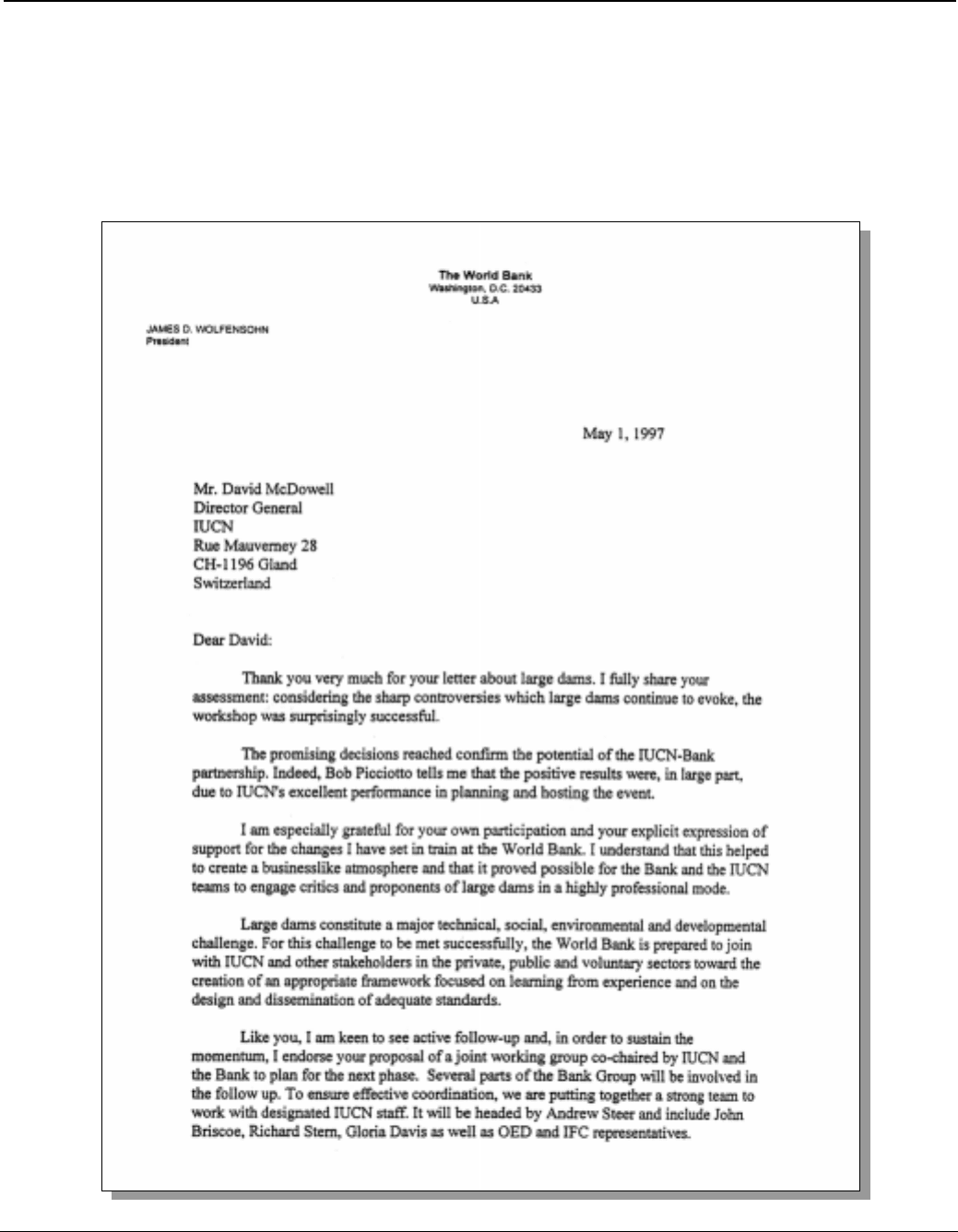

Appendix B 137

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:48 PM Page 145

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:48 PM Page 146

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

Appendix C 139

APPENDIX C1:

LIST OF PAPERS AVAILABLETO THE WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS

Author Title Date

Michael Acreman Environmental Effects of Hydro-Electric December 1996

in J.CIWEM Power Generation in Africa and

the Potential for Artificial Floods

John Besant-Jones Guidelines for Attracting Developers April 1996

in Energy Issues: World Bank of Hydropower Independent

Power Projects

Shripad Dharmahikary A Critique of the World Bank April 1997

OED Review of Large Dams and

Suggestions for the Future Process

Earth Island Journal Tropical Dams and Global Warming 1996

The First International Curitiba Declaration: March 1997

Meeting of People Affirming the Right to Life

Affected by Dams and Livelihood of People

Affected by Dams

Robert Goodland The Urgent Need April 1997

and Salah El Serafy to Internalize CO

2

Emission Costs

Nicholas Hildyard Public Risk, Private Profit— July/August 1996

in The Ecologist The World Bank and the Private Sector

International Commission Position Paper on Dams and November 1995

on Large Dams the Environment

International Commission Some Inescapable Facts April 1997

On Large Dams Which May Put the Issue

in Perspective

International Rivers Network Risky Business January 1996

in World Rivers Review

International Rivers Network Manibeli Declaration: June 1994

in conjunction with NGOs Calling for a Moratorium on

from the around the world World Bank Funing of Large Dams

E.A.K. Kalitsi Management of Multipurpose April 1997

Reservoirs — The Volta Experience

Franklin Ligon, William Dietrich Downstream Ecological April 1997

and William Trush in Bioscience Effects of Dams

APPENDIX C: Papers Available at the Workshop, Participant Biographies

THE BOOK - Q 7/25/97 4:48 PM Page 147

LARGE DAMS: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future

140 Appendix C

Author Title Date

Patrick McCully A Critique of “The World Bank’s April 1997

Experience with Large Dams:

A Preliminary Review of Impacts”

Jeffrey McNeely How Dams and Wildlife Can Coexist: October 1987

in Conservation Biology Natural Habitats, Agriculture and Major Water

Resource Development Projects in Tropical Asia

Bradford Morse Letter to the President of the World Bank June 1992

and Thomas Berger Regarding the Independent Review

of the Sardar Sarovar Dam and Irrigation Projects

Charlie Pahlman Build-Operate-Transfer October 1996

in Watershed

Brian Smith Presented at Guidelines for Considering the Needs of February 1997

the IUCN Workshop on the River Dolphins and Porpoises During the Planning

Effects of Water Development and Management of Water Developmpent Projects

on River Dolphins in Asia

Theo P.C. van Robbroeck Presented Future Water Supplies Threatened– 1996

at the Sixteenth Congress of the Large Dams: A Bane or a Boon?

International Commission on Irrigation

and Drainage

Theo P.C. van Robbroeck Reservoirs: Bane or Boon? 1996

Presented at the Geoffrey Binnie Lecture

World Bank in OED Precis Lending for Irrigation March 1995

World Bank in OED Precis Learning from Narmada May 1995

World Bank in OED Precis Environmental Assessments December 1996

and National Action Plans

World Bank OD 4.00 Annex B: Environmental Policy for April 1989

Dam and Reservoir Projects

World Bank OD 4.01: October 1991

Environmental Assessment

World Bank OP 4.04: Natural Habitats September 1995

World Bank OD 4.20 Annex A: Indigenous Peoples September 1995

World Bank OD 4.30: Involuntary Resettlement June 1990

World Bank OP 10.04 Economic Evaluation of September 1994

Investment Operations

World Bank OP 4.37 Safety of Dams September 1996

US Bureau of Reclamation, Remarks to the International November 1994

Daniel Beard Commission on Large Dams

THE BOOK - Q•eppx 8/1/97 6:30 AM Page 148