The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE TRANSMISSION OF CH'AN BUDDHISM 589

been those of the Northern school of

Ch'an.

By the Sung dynasty, the

rather contemplative Northern teaching had been outstripped by the

Southern school deriving from Hui-neng, the sixth Ch'an patriarch,

' which stressed a dynamic meditation leading to "sudden enlighten-

ment."

7

In the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, Southern-

school masters tracing their Ch'an lineage from Lin-chi were the most

influential. Their Ch'an practice harnessed mind-breaking "cases"

(kung-an, koan), shouts, and even slaps to intensify their students'

meditative quest. Japanese monks also found that this meditation prac-

tice was conducted in a novel monastic setting in which the monks'

hall, where they practiced communal meditation, and the Dharma, or

lecture, hall, where the monks debated Ch'an publicly with their mas-

ters,

were among the most important buildings. They found that

Ch'an masters stressed the Vinaya precepts and that a detailed code of

monastic regulations for the Ch'an communities, the Ch'an-yuan

ch'ing-kuei,

had recently been compiled (1103) and was in force in

many Ch'an communities.

8

Those monks who stayed longer in China

discovered that many Ch'an masters shared the intellectual and cul-

tural interests of the secular literati with whom they consorted. They

also learned that monastic life included not only meditation and study

of Ch'an Buddhist traditions and texts but also a wide range of cultural

avocations such as poetry, painting, and scholarship, many of which

blended Ch'an and secular taste.

Young Japanese monks found the Ch'an Buddhism in the monaster-

ies of Hangchow to be vigorous and impressive. It was natural that

they should have viewed Ch'an as the highest expression of Sung

Buddhism and sought to use it to revitalize Japanese monastic Bud-

dhism. When they discovered that the Tendai establishment in the

capital resisted such reform, that Zen as a single practice was de-

nounced as vociferously as Honen's exclusive

nembutsu

practice had

been, the Zen pioneers were forced to try to establish Zen as an

independent branch of Buddhism in Japan under the patronage of new

groups in medieval society.

The first monks to introduce Sung Ch'an teachings to Japan were

Myoan Eisai (1141-1215) and Kakua (1143-?). Eisai made two jour-

neys to China, the first in 1168 and the second in 1187. His first stay in

7 The place of Hui-neng and the differences between the northern and southern branches of

Ch'an Buddhism are discussed by Philip Yampolsky in his introduction to

The

Platform Sutra

of

the

Sixth

Patriarch

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1967), pp. 1-57.

8 Kagamishima Genryu, Sato Tatsugen, and Kosaka Kiyu, eds.,

Yakuchu

Zerion

shingi

(Tokyo:

Sotoshu shumucho, 1972), pp. 1-25.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

590 ZEN AND THE GOZAN

China lasted for only a few months and was devoted to visiting tradi-

tional Buddhist sites and collecting Tendai and Shingon texts. Eisai's

interest in Ch'an had been whetted, but after his return to Japan he

seems to have continued to advocate Tendai Buddhism. His second

pilgrimage to China lasted for three years and brought him into much

deeper contact with Ch'an. Having been refused permission to pro-

ceed through China to visit the Buddhist sites in India, Eisai made his

way to Mount T'ien-t'ai where he studied Ch'an under Hsu-an Huai-

chang of the Huang-lung lineage of the Lin-chi school. Hsu-an gave

Eisai a certificate of enlightenment and urged him to spread Zen

throughout Japan. Eisai was able to establish several meditation halls

in Kyushu, but when he tried to promote Zen in the capital, suggest-

ing that it be given pride of place in Tendai practice and arguing that

the secular patronage of Zen would contribute to the country's secu-

rity, he ran afoul of the monks and supporters of the Enryakuji and

was driven out of Kyoto. Making his way to eastern Japan, Eisai

secured the patronage of Ho jo Masako and the young shogun Mina-

moto Sanetomo. With their backing Eisai eventually was able to re-

turn to Kyoto and establish the Kenninji, where Zen meditation was

taught together with Tendai and Shingon Buddhist practices.

9

Kakua may have introduced Sung Zen teachings to Japan even

before Eisai. In

1171,

he learned that Ch'an was in vogue in China and

made a four-year journey to the continental monasteries. He had re-

turned to Japan before Eisai made his second visit to China. According

to the

Genko

shakusho,

a history of Buddhism compiled in 1322 by the

Zen monk Kokan Shiren, Kakua bemused emperor Takakura by re-

sponding to his questions about Zen with a melody on the flute. But

because Kakua did not establish an enduring lineage, the credit for

founding Rinzai Zen in Japan went to Eisai.

10

By the mid-thirteenth century at least thirty Japanese monks had

journeyed to China in search of Zen. A number of them studied at the

Hangchow monastery of Ching-shan under the guidance of Wu-chun

Shih-fan (1177-1249) of the Yang-ch'i lineage of Rinzai Zen." In the

9 Yanagida Seizan, Rinzai no kafu (Tokyo: Chikuma shobo, 1967), pp. 28-88, offers a bio-

graphical study of Eisai (or, as he is also known, Yosai).

10 Kokan Shiren, "Genko shakusho" in Kuroita Katsumi, ed., Shimei zoho kokushi laikei (To-

kyo:

Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1930), vol. 31, p. 100.

11 The fine portrait of Wu-chun given to Enni and carried back by him to Japan is illustrated in

the catalogue for the exhibition The Arts of Zen Buddhism held at the Kyoto National

Museum, October-November 1981. See Kyoto kokuritsu hakubutsukan, ed., Zen no

bijutsu

(Kyoto: Kyoto kokuritsu hakubutsukan, 1981), pp. 25, 55. An example of his calligraphy is

discussed in Jan Fontein and Money L. Hickman, eds., Zen Painting and Calligraphy (Bos-

ton: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1970), pp. 24-26.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE TRANSMISSION OF CH'AN BUDDHISM 591

transmission of Zen to Japan, the most influential of

these

monks were

Dogen Kigen, Enni Ben'en, and Muhon (Shinchi) Kakushin.

Dogen (1200-53) entered the Tendai monastery of Enryakuji at the

age of thirteen. Not finding answers to his religious questioning in

Tendai Buddhism, he moved to the Kenninji to study Zen with Eisai.

In 1223, in company with Eisai's most senior disciple Myozen, Dogen

journeyed to China. After studying under several Ch'an masters,

Dogen met T'ien-t'ung Ju-ching (1163-1228),

a

Ts'ao-tung (Soto) Zen

master reputed for his austere personal life and severe Zen practice.

The elderly Chinese master and the enthusiastic young Japanese monk

established an immediate rapport. Before Dogen returned to Japan,

Ju-ching recognized Dogen's enlightenment and transmitted to him

the teachings of Soto Zen. Dogen found it difficult, however, to gain

acceptance for his Zen in the capital. He returned at first to the

Kenninji, but Eisai had died, and the Zen training there had deterio-

rated. Dogen's advocacy of single-minded meditation

(shikan

taza) as

the best form of Buddhist practice aroused the hostility of the

Enryakuji monks. Their opposition eventually forced him to leave the

capital and establish his community in the mountains of Echizen.

With the exception of one brief visit to Kamakura, where he discussed

Zen with the regent Ho jo Tokiyori, he spent the remainder of his life

there, building the monastic center of Eiheiji, training the few disci-

ples who came to study with him, and writing his treatises on Zen and

the monastic life, the

Shobo

genzo.

12

Enni Benn'en (1202-80) was more successful than Dogen had been

in gaining acceptance for Zen in Kyoto. As a young monk, Enni

studied Zen with Eisai's disciple Eicho after becoming dissatisfied

with Tendai Buddhism. In 1235, he set out on a six-year pilgrimage to

China. There he became a disciple of Wu-chun Shih-fan at Ching-

shan. Wu-chun gave to Enni a robe and bowl symbolizing the legiti-

mate transmission of Zen enlightenment and urged him to spread Zen

throughout Japan. On his return to Japan in

1241,

Enni brought with

him many Zen-related texts, as well as portraits of Wu-chun and exam-

ples of his calligraphy.

Eisai, Kakua, and Dogen had not been readily accepted in Kyoto.

Enni, however, secured a stronger beachhead for Zen in the capital

largely because he enjoyed the sponsorship of one of the most influen-

tial nobles of the day, Kujo Michiie. In 1243, Enni was invited to

12 This biographical sketch of Dogen is based on Imaeda Aishin,

Dogen:

zazen

hitosuji

no shamon

(Tokyo: NHK Books, 1981); and Hee-jin Kim, Dogen Kigen - Mystical Realist (Tucson:

University of Arizona Press, 1975).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

592 ZEN AND THE GOZAN

Kyoto to serve as the founding abbot of a grandiose new monastery,

the Tofukuji, that Michiie had built. The Tofukuji was not at first

exclusively a Zen monastery. Rather, Enni was forced to compromise

with established Buddhism and, like Eisai at the Kenninji, to teach

Zen alongside Tendai and esoteric Buddhism. Enni, however, made it

clear that he considered Zen the fundamental Buddhist practice and

worked to convert the Tofukuji into a full-fledged Zen monastery.

Enni's learning, his firsthand knowledge of Chinese Buddhism, and

the patronage of the Kujo family guaranteed his acceptance by the

Buddhist circles close to the court. On several occasions, Enni lec-

tured on Zen to Emperor Gosaga and his entourage and taught Zen to

the warrior rulers of eastern Japan. In his long lifetime, Enni attracted

large numbers of disciples, many of whom in their turn went to study

under Wu-chun and his successors.

13

Muhon (Shinchi) Kakushin (1207-98) was in his thirties before he

began to practice Zen with Eisai's disciples Gyoyu and Eicho in east-

ern Japan. In 1249, he traveled to China where he studied Ch'an under

the Lin-chi master Wu-men Hui-k'ai (Mumon Ekai), the compiler of

the collection of

koan,

(literally, "public cases") known in Japanese as

the

Mumonkan

(Gateless

gate).

Koan

were conundrums or propositions

used as an aid to Buddhist meditation and enlightenment. Kakushin

was certainly one of the first monks to use

koan

from this collection in

his training of Zen monks in Japan. Unlike Enni, however, he had

little desire to head a great temple in the capital. Although he was

invited to Kyoto by the cloistered emperors Kameyama and Gouda,

who wished to learn about Zen and offered to build temples for him,

Kakushin preferred an eremitic life at a small mountain temple, the

Kokokuji, in Kii Province.

14

Japanese monks like Mukan Fumon or Tettsu Gikai, who had stud-

ied Zen under Enni and Dogen, respectively, continued to journey to

China during the second half of the thirteenth century. But by the time

Kakushin returned to Japan in 1254, a new and important stage in the

transmission of Sung Zen was under

way.

Chinese Ch'an masters were

beginning to come to Japan to teach Zen and the conduct of Zen

monastic life. The young Japanese monks enrolling in Chinese monas-

teries had conveyed to the Chinese monks both their enthusiasm for

13 For the life of Enni, see the chronology compiled by his follower Enshin, "Shoichi kokushi

nempu," in Suzuki gakujutsu zaidan, ed., Dai-Nihon Bukkyo zensho (Tokyo: Kodansha,

1972),

vol. 73, pp. 147-56; and the section by Tsuji Zennosuke in Nihon Bukkyo-thi(chusei2)

(Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1970), pp. 98-124. A painting of

the

Tofukuji in the early sixteenth

century is illustrated and described in Fontein and Hickman, eds., Zen

Painting

and Calligra-

phy, pp. 144-8. 14 Entry on Kakushin in Zengaku diaijilen.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE TRANSMISSION OF CH'AN BUDDHISM 593

Zen and the information that Zen was taking root in Japan. As a

result, some Chinese Ch'an masters came to view Japan as a possible

field for the transplanting of Zen.

The first of these Chinese monks to come to Japan was Lan-ch'i

Tao-lung (Rankei Doryu, 1213-78). Although still only in his early

thirties when he landed in Kyushu in 1246, Lan-ch'i was a recognized

Ch'an master who had practiced meditation under the guidance of

Wu-chun Shih-fan and Wu-ming Hui-hsing, the leading Lin-chi mas-

ters of that time. The young Chinese monk made his way to

Kamakura where he won the favor of the regent Hojo Tokiyori.

Tokiyori studied Zen with Lan-ch'i and installed him as the founding

abbot of a new Zen monastery, the Kenchoji, in Kamakura. The

completion of the Kenchoji in 1253 was an important milestone in the

transmission of Zen to Japan. Unlike the Kenninji and Tofukuji in

Kyoto, it did not begin by compromising with the older schools of

Buddhism. The temple bell and the plaque over the main gate pro-

claimed that it was a Zen monastery. Unlike Dogen's community at

Eiheiji, which had rejected any accommodation with Tendai or other

forms of Buddhism and as a result had discouraged elite patronage,

the Kenchoji had the backing of the country's warrior rulers.

The establishment of the Kenchoji signaled that Zen Buddhism was

now a major force in Japanese religious life. But Lan-ch'i did not

restrict himself to Kamakura. In 1265, in response to an imperial

request, he went to Kyoto and lectured at the court. While in the

capital he revitalized Zen practice at Eisai's old monastery, the

Kenninji, and helped Enni transform the Tofukuji into a full Zen

monastery. During the Mongols' first invasion attempt in 1274, it was

rumored that Lan-ch'i was a Mongol spy. Subsequently, when he was

exiled to Kai Province, he took the opportunity to spread Rinzai Zen

among the local warriors. Lan-ch'i was allowed to return to the

Kenchoji shortly before his death. In recognition of his contribution to

the transmission of Zen, he was granted the posthumous title of

Daikaku Zenji, Zen master Daikaku. His disciples and successors in

the Daikaku lineage, with Kenchoji as their base, carried his Zen

teachings throughout the Kanto region.

15

Lan-ch'i had been followed before the close of

the

Kamakura period

by more than a dozen fully trained Chinese Ch'an masters. This was a

15 Lan-ch'i Tao-lung and Kenchoji are discussed in Daihonzan Kenchoji, ed., Kyofukuzan

Kenchoji (Kamakura: Daihonzan Kenchoji, 1977), pp. 23-82. Portraits of Lan-ch'i and

Tokiyori, temple ground plans, and examples of Lan-ch'i's calligraphy and monastic regula-

tions are also included in this source.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

594 ZEN AND THE GOZAN

rare phenomenon in Sino-Japanese cultural relations, and after the

Nara period there was no other comparable influx of fully trained,

high-ranking monks. Some came because they felt uprooted by the

Mongol conquest of China. Others responded to invitations from the

Hojo regents. Others came simply because, like Lan-ch'i, they had

heard that Zen was in the ascendant in Japan. A few of these emigres,

for instance, Wu-an P'u ning (Gottan Funei, 1197-1267), returned to

China disappointed with their Japanese students' incomprehension of

Zen. Most, however, spent the remainder of their lives in Japan,

training monks and lay persons in Kamakura, Kyoto, and the prov-

inces,

where they were invited to establish temples by powerful local

shugo

warriors. Through their efforts, the practice of Zen in the Japa-

nese monasteries by the early fourteenth century was probably equiva-

lent to that in the Chinese monasteries.

16

The Muromachi

period

Throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Japanese monks -

now well trained in Zen before their departure - continued to travel to

Chinese Ch'an centers in search of teachings, monastic codes, and

cultural expressions of

Zen.

Some of them spent more than a decade in

China and rose to high ranks in Chinese monasteries. Others were sent

by their temples or by the Ashikaga shoguns to head embassies, to act

as interpreters, and to handle foreign trade and cultural exchanges.

These latter may have made very little contribution to the transmis-

sion of Zen.

By 1350, the Zen monastic establishment in Japan was so large, well

organized, and self-sustaining that there was less incentive for Chinese

monks to come to Japan or for Japanese monks to undergo training in

Chinese monasteries. Monks who had been to China were highly re-

spected, not least by provincial warrior chieftains eager to sponsor Zen

in their domains, but it was no longer essential to have studied Zen in

China or to have had one's enlightenment certified

(inka)

by a Chinese

master in order to be a leading figure in Japanese Zen circles.

The influential monk Muso Soseki (1275-1351) represented this

first generation of self-confident Japanese Rinzai masters. Muso had

begun his Zen practice under the guidance of the Chinese emigre

monk I-shan I-ning (Issan Ichinei, 1247-1317) but had failed to attain

16 Information on some of these Chinese masters and their patrons can be found in Tsuji, Nikon

Bukkyo-shi (chiisei 2), pp. 125-264; and Martin Collcutt, Five Mountains: The Rinzai Zen

Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981),

pp.

57-78.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE TRANSMISSION OF CH'AN BUDDHISM 595

I-shan's recognition of his enlightenment. I-shan described Muso's

approach to Zen as too bookish. After further wandering and intense

meditation, Muso attained enlightenment at dawn in a mountain hut,

on seeing dying embers burst into renewed fire. This experience was

accepted as a true enlightenment by the Japanese Zen master Koho

Kennichi (1241-1316), a son of Emperor Gosaga. Muso subsequently

became one of the most influential Zen monks in medieval Japan. He

was patronized by emperors and shoguns, headed many of the leading

Zen monasteries in Kyoto and Kamakura, and attracted many hun-

dreds of disciples. Some of these disciples went to China. Muso, how-

ever, never made the journey. He declared that with Zen so well rooted

in Japan, there was no longer any need to look to China as a source of

transmission.

17

Muso's contemporaries Daito and Kanzan, the found-

ers of the Daitokuji and the Myoshinji, likewise never visited China.

War in Japan and piracy in East Asian waters during the late fif-

teenth and sixteenth centuries virtually ended the direct transmission

of Zen from Chinese monasteries. Beginning in the late sixteenth

century, however, commercial contacts between Japan and China re-

covered, and a community of Chinese merchants settled in Nagasaki.

In the seventeenth century, in response to their requests for spiritual

leadership, Chinese monks from Fukien Province began to come to

Nagasaki. Among them was Yin-yuan Lung-chi (Ingen Ryuki, 1592-

1673),

an

eminent Ch'an master of the Huang-po (Obaku) school.

Yin-yuan came to Nagasaki in 1654 to serve as the abbot of the

Kofukuji. His reputation soon came to the attention of the fourth

Tokugawa shogun, Ietsuna, who first invited him to Edo and then

sponsored the building of a new monastery at Uji, near Kyoto, called

the Mampukuji, a Japanese reading of the name of the monastery in

Fukien from which Yin-yuan had come. Yin-yuan and the Chinese

masters of the Huang-po school who followed him to Japan to head the

Mampukuji or its branches introduced a new type of Zen common in

Ming Chinese monasteries in which Zen meditation and koan study

were allied with Pure Land

nembutsu

devotion.

18

Obaku Zen did not

become a very large school, however. At its peak it probably included

no more than several hundred temples. The novel syncretic Ming Zen

teachings and monastic practices, nonetheless, presented a challenge

to the established Rinzai and Soto schools which were sunk in a late

medieval lethargy. Many Rinzai and Soto monks were strongly at-

tracted by

nembutsu

Zen. Others, like Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768),

17 Tamamura Takeji, Muso Kokushi (Kyoto: Heirakuji shoten, 1969).

18 On Yin-yuan, the Obaku school, and Mampukuji, see Fuji Masaharu and Abe Zenryo, eds.,

Mampukuji (Kyoto: Tankosha, 1977).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

596 ZEN AND THE GOZAN

vigorously rejected such syncretic tendencies, but in doing so they

encouraged a revival of serious Zen practice in both the Rinzai and

Soto monasteries.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ZEN MONASTIC

INSTITUTION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN

When Eisai returned from his second pilgrimage to China in

1191,

no

Zen monasteries existed in Japan. But, a century later, Zen had taken

root, and by 1491 there were many thousands of Rinzai and Soto Zen

monasteries, subtemples, branch temples, nunneries, and hermitages

scattered throughout the country.

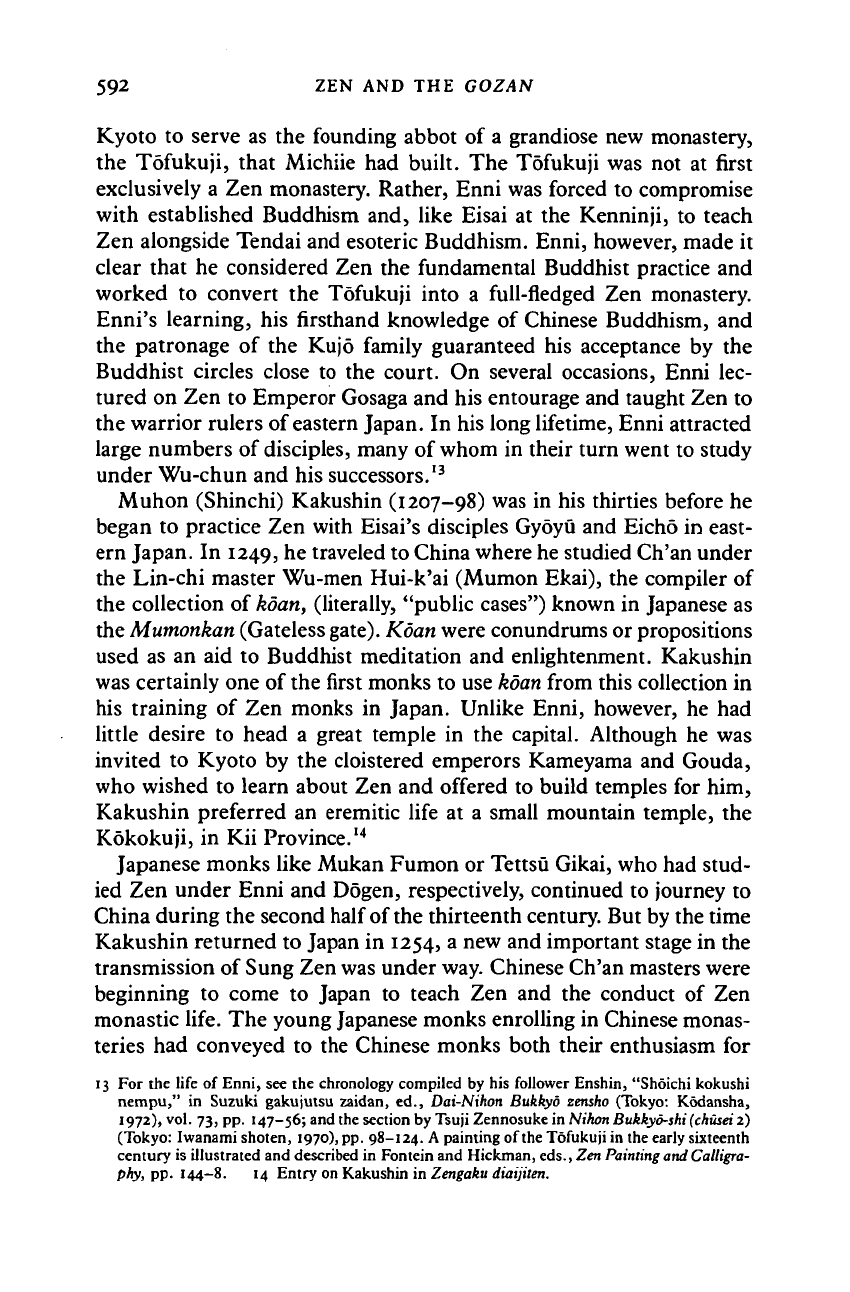

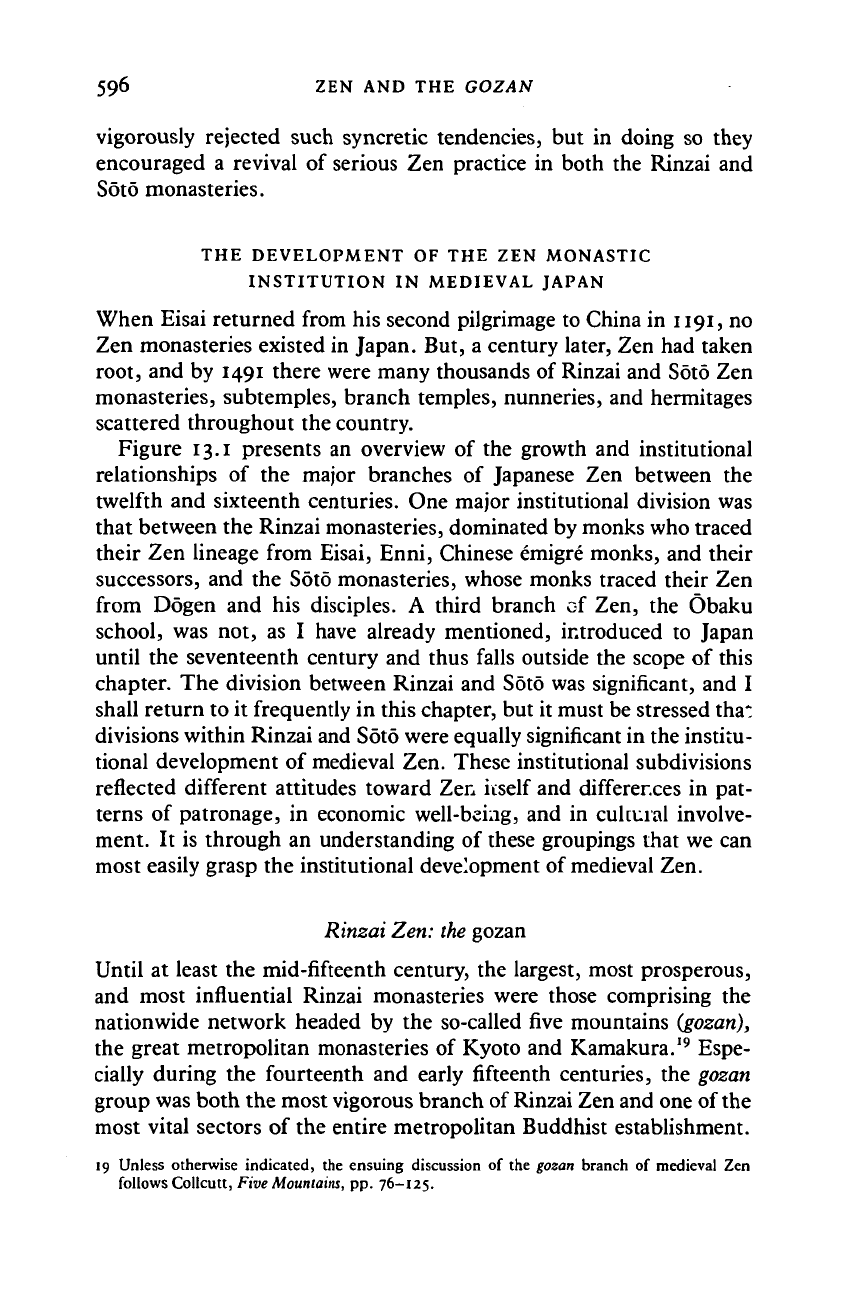

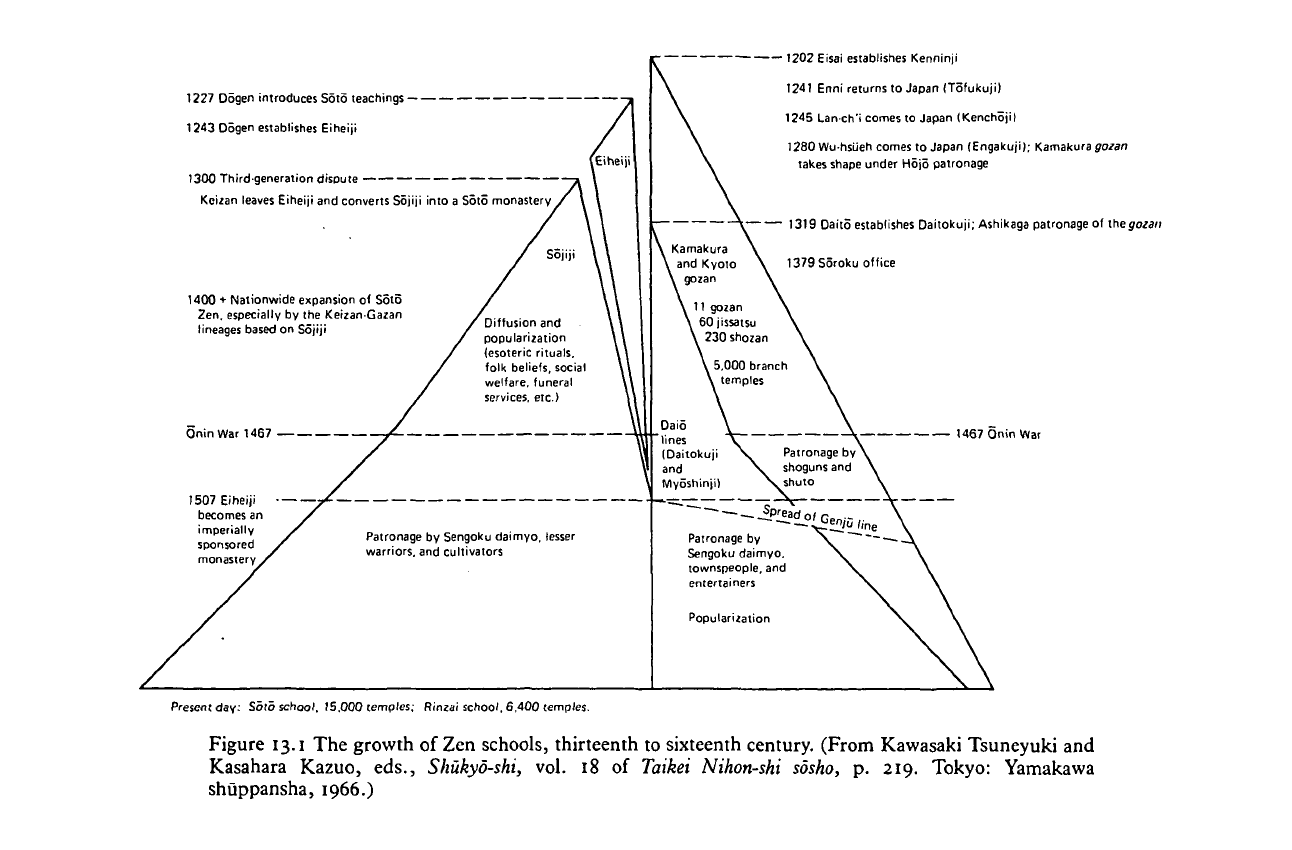

Figure 13.1 presents an overview of the growth and institutional

relationships of the major branches of Japanese Zen between the

twelfth and sixteenth centuries. One major institutional division was

that between the Rinzai monasteries, dominated by monks who traced

their Zen lineage from Eisai, Enni, Chinese emigre monks, and their

successors, and the Soto monasteries, whose monks traced their Zen

from Dogen and his disciples. A third branch of Zen, the Obaku

school, was not, as I have already mentioned, introduced to Japan

until the seventeenth century and thus falls outside the scope of this

chapter. The division between Rinzai and Soto was significant, and I

shall return to it frequently in this chapter, but it must be stressed that

divisions within Rinzai and Soto were equally significant in the institu-

tional development of medieval Zen. These institutional subdivisions

reflected different attitudes toward Zen itself and differences in pat-

terns of patronage, in economic well-being, and in cultural involve-

ment. It is through an understanding of these groupings that we can

most easily grasp the institutional development of medieval Zen.

Rinzai Zen:

the

gozan

Until at least the mid-fifteenth century, the largest, most prosperous,

and most influential Rinzai monasteries were those comprising the

nationwide network headed by the so-called five mountains {gozan),

the great metropolitan monasteries of Kyoto and Kamakura.

19

Espe-

cially during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, the gozan

group was both the most vigorous branch of Rinzai Zen and one of the

most vital sectors of the entire metropolitan Buddhist establishment.

19 Unless otherwise indicated, the ensuing discussion of the gozan branch of medieval Zen

follows Collcutt, Five Mountains, pp. 76-125.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1227 DSgen introduces Soto teachings —

1243 Dogen establishes Eiheiji

1300 Third-generation dispute

Keizan leaves Eiheiji and converts Sojiji into a Soto monastery

1400 + Nationwide expansion of Soto

Zen.

especially by the Keizan-Gazan

lineages based on Sojiji

1202 Eisai establishes Kenninji

1241 Enni returns to Japan (Tofukuji)

1245 Lanch'i comes to Japan (Kenchojil

1280 Wuhsueh comes to Japan (Engakuji); Kamakura gazan

takes shape under Hojo patronage

; \ 1319 Oaito establishes Daitokuji; Ashikaga patronage of the goian

1379 Soroku office

Kamakura

and Kyoto

gozan

11 gozan

60 jissatsu

230 shozan

Diffusion and

popularization

(esoteric rituals,

folk beliefs, social

welfare, funeral

services, etc.)

5,000 branch

temples

Daio

nes

(Daitokuji

and

Wlyoshinji)

Patronage by

shoguns and

shuto

1507 Eiheiji

becomes an

imperially

sponsored

monastery

Patronage by Sengoku daimyo, lesser

warriors, and cultivators

Patronage by

Sengoku daimyo.

townspeople, and

entertainers

Onin War 1467

1467 Onin War

Present day: Sato school. 15,000 temples; Rinzai school,

6,400

temples.

Figure 13.i The growth of Zen schools, thirteenth to sixteenth century. (From Kawasaki Tsuneyuki and

Kasahara Kazuo, eds., Shukyo-shi

y

vol. 18 of Taikei Nihon-shi sdsho, p. 219. Tokyo: Yamakawa

shuppansha, 1966.)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

598 ZEN AND THE GOZAN

The development of the

gozan

institution was of great significance, not

merely for the diffusion of Zen, but also for the cultural, political, and

economic life of the age.

Gozan

monasteries had as their patrons mem-

bers of the warrior and courtly elites. They were major landholders

and collectively were one of the largest holders of private domain

(shoen) interests in medieval Japan. Their monks, who must be

counted among the intellectuals of the age, were well versed in Chinese

culture as well as in Zen and served as cultural and political advisers to

shoguns and emperors besides being mentors in Zen to the sons and

daughters of warrior families. The gozan group comprised a three-

tiered hierarchy of monasteries. All adopted the same basic organiza-

tional structure, and although they differed greatly in size and impor-

tance, they all were regulated by the same monastic codes, and were

subject to the same control by warrior laws. A youth entering one of

the small provincial monasteries making up the lower tier of the

gozan

system might in time become a Zen master or monastic official in one

of the Kamakura or Kyoto

gozan.

Conversely, Zen teachings or Chi-

nese cultural tastes adopted by the metropolitan

gozan

quickly spread

to the system's provincial extremities.

The gozan institution began to take shape in the late thirteenth

century. By 1299, the Kamakura monastery of Jochiji was being re-

ferred to as one of "five mountains." A Kenchoji document of 1308

states that that monastery was then regarded as the "head of the five

peaks."

At about the same time, the newly established Kyoto monas-

tery of Nanzenji was also being described as one of

the

five

mountains.

Details of the early

gozan

network are unclear, but the surviving rec-

ords indicate that the Hojo regents in Kamakura took the initiative in

honoring and regulating the new Zen monasteries that they were build-

ing, by adopting the Southern Sung practice of organizing an official

three-tiered hierarchy of Zen monasteries. Together with the appoint-

ment of monasteries to

gozan

status, the Hojo also designated smaller

monasteries in Kamakura, Kyoto, and the provinces to the second and

third tiers of the hierarchy as

jissatsu

("ten temples") and

shozan

("vari-

ous mountains"). Most of the monasteries included in the

gozan

were

Rinzai monasteries dominated by those schools of Zen derived from

Eisai, Enni, or Chinese emigre masters that had taken root in

Kamakura and Kyoto. Sot 6 Zen was represented in the

gozan

system

by a very small number of monasteries that had been founded in

Kamakura.

Why should the Hojo have shown such interest in creating a Zen

monastic establishment? In part they were probably responding to

suggestions by Chinese and Japanese monks who were eager that their

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008