The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE WORLD OF TEA 499

function of the chanoyu and the deliberate use by warlords of the tea

master as a go-between, a negotiator, and even a diplomat. It was the

tea master Imai Sokyu (1520-93), for example, who finally arranged

the peaceful submission of the city of Sakai to Nobunaga during the

latter's march to power in 1568. Both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi em-

ployed tea masters, including Sen no Rikyu, to perform various politi-

cal as well as cultural services for them. Rikyu, we are told, became so

influential under Hideyoshi that no one could see the hegemon with-

out first securing his approval.

Sen no Rikyu is the most fascinating figure of the Azuchi-

Momoyama epoch because he symbolizes more than anyone else the

clashes and pulls of the cultural history of the waning medieval age

and the beginning of the early modern period. Even as he perfected

wabicha, he abetted Hideyoshi the parvenu in his penchant for vulgar

display. But in the end Rikyu ran afoul of Hideyoshi, who was ever

capable of acting on a tyrannical whim, and in 1591 he was condemned

to commit suicide.

71

With Rikyu's death the last major force of medi-

eval culture was spent, and there was nothing left to impede further

development of the more "modern" aspects of Azuchi-Momoyama

culture.

71 Historians cannot determine the precise reasons for this severe punishment. Included among

the possibilities are that Rikyu personally offended Hideyoshi's vanity or that he was sacri-

ficed to appease a political faction that opposed him.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

11

THE OTHER SIDE OF CULTURE IN

MEDIEVAL JAPAN

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ISSUES

Historians transform lived life into narrated life, and in this sense they

are not unlike novelists. Intent notwithstanding, neither history nor

novel copies human experience but, rather, selects, focuses, and retells

and thereby inevitably reshapes. Even subtraction adds something

new. And so though we go to both historians and novelists for "truth,"

both are inherently disposed to falsification.

By selecting and subtracting, the interpretations of Japanese cul-

tural history to date, particularly those of the Kamakura and

Muromachi eras (roughly the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries)

have focused on the "high" culture of the period; on the activities of

the political, religious, and intellectual leaders of the time; and on the

achievements of their close associates, eminent artists, architects, writ-

ers,

and performers. Even those historians who are interested in the

culture of ordinary people tend to view them in comparison with the

upper classes, and their accounts are thereby riveted to the same high-

low polarity as are those of the historians with whom they are ideologi-

cally at odds. Ironically, therefore, an elite veneer stretches over the

history of the middle ages, obscuring the texture and contours of the

daily life of the great majority of medieval men and women, while

leaving in darkness those creators of Japanese culture who have failed

to qualify under these preferred definitions of history.

It is not that such lives are beyond historical retrieval. On the

contrary, throughout the middle ages the daily life of ordinary citizens

was often a subject of

note,

even in the diaries and historical records of

the elite; it is therefore much more easily resurrected than might be

imagined. We are fortunate, further, in having a rich tradition of

medieval paintings, statues, fiction, and songs, all of which preserve a

realistic depiction of the period's life. Through these works we are

This chapter was originally presented and discussed in European and American forums under

the title "The Other Side of History: In Search of the Common Culture of Medieval Japan."

500

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ISSUES 501

able to look in on the common culture of medieval Japan and to

perceive it as it was experienced by men and women from all levels of

society.

This chapter will aim, therefore, at revision. It will examine signifi-

cant concerns of the Japanese middle ages - indeed, significant cre-

ators of Japanese culture - that have gone unnoted, unheeded, or even

disdained. I do not refer here to the culture of commoners as opposed

to that of courtiers, nor do I contrast "popular" with "elite," as I am

not convinced that primary sources permit so convenient a dichotomy.

If I use the word

popular,

I shall do so with regard to those aspects of

a

nation's culture valued by most of its citizens, crossing all lines of

class,

sex, and generation. The common culture that I seek are those

attitudes and activities known to all and esteemed by that same major-

ity, high and low. A common culture is one that has outgrown the

exclusive ownership of any gender, group, or coterie in society, high or

low, and has become the property of all.

We must recognize that historical constructs have been built around a

conceptual vocabulary frozen by class, gender, and status preclusions.

This had led to a favoring of certain topics of research and a denigration

of other features of Japan's culture that do not fit the dominant para-

digm. History, like court poetry, has been written from a canonized list

of preselected topics, with most aspects of ordinary life excluded.

To complicate matters, the Japanese middle ages comprised not an

elite and a popular culture but a variety of cultures - those of farmers,

warriors, fisherfolk, courtiers, urban working people, and religious

practitioners, for example - and within each, the cultures of the

young, the middle-aged, the old, and so on. But if there is one marked

characteristic of the medieval years, it is the clear sense of a coming

together for the first time, of a sense of national community. Emanat-

ing from the expressive arts of song, dance, mime, and narrative are

self-perceptions, community perceptions, revelations regarding social

contracts, and struggles with the margins of tolerated behavior that

help us see better those perimeters.

The use of such "fictions" as painting, song, and narrative in the

writing of history has, for some critics, occasioned inordinate skepti-

cism. Yet historians have embraced historical records far more contami-

nated; for example, "In the Gukansho it is impossible to separate the

history from the dogma."

1

And genealogical forgery, even the buying

1 Toshio Kuroda, "Gukansho and Jinno Shotoki: Observations on Medieval Historiography," in

John A. Harrison, ed., New Light on Early and Medieval Japanese

Historiography

(Gainesville:

University of Florida Monographs, Social Sciences no. 4, Fall 1959), p. 39.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

5O2 THE OTHER SIDE OF CULTURE

of family trees, was a common way of life for some during various

centuries in Japanese history.

2

On the other hand, to be accepted by

medieval Japanese citizens, fiction, painting, and song had to ring

true.

Thus, they are useful to historians precisely because behind their

narratives are implicit agreements about the nature of the social experi-

ence;

they organize what is deemed significant and represents knowl-

edge of the daily universe. Knowledge of this kind is no less true than

the symbolic representation in a statistical account. Literature and art

are,

in effect, the staging of collective experience. And they perhaps

have an even greater authenticity than does fact because they represent

the "truth" as fidelity to social expectation.

The story of every nation is that of both unique historical events and

recurring events, events that are the habits of

a

people.

For medieval Japan, such recurring patterns include the tonsure

(cutting or shaving off the hair and taking religious vows), the selling

of children, pilgrimage, the enjoyment of dance, the need to talk to the

spirits of the dead, or the talismanic function of the vocalized word.

The great power of the medieval song or the bard's narrative, like that

of their counterparts today, lies wholly in this generic nature, in the

likelihood of the tale it

tells.

One is moved because one knows that this

is the way things really are.

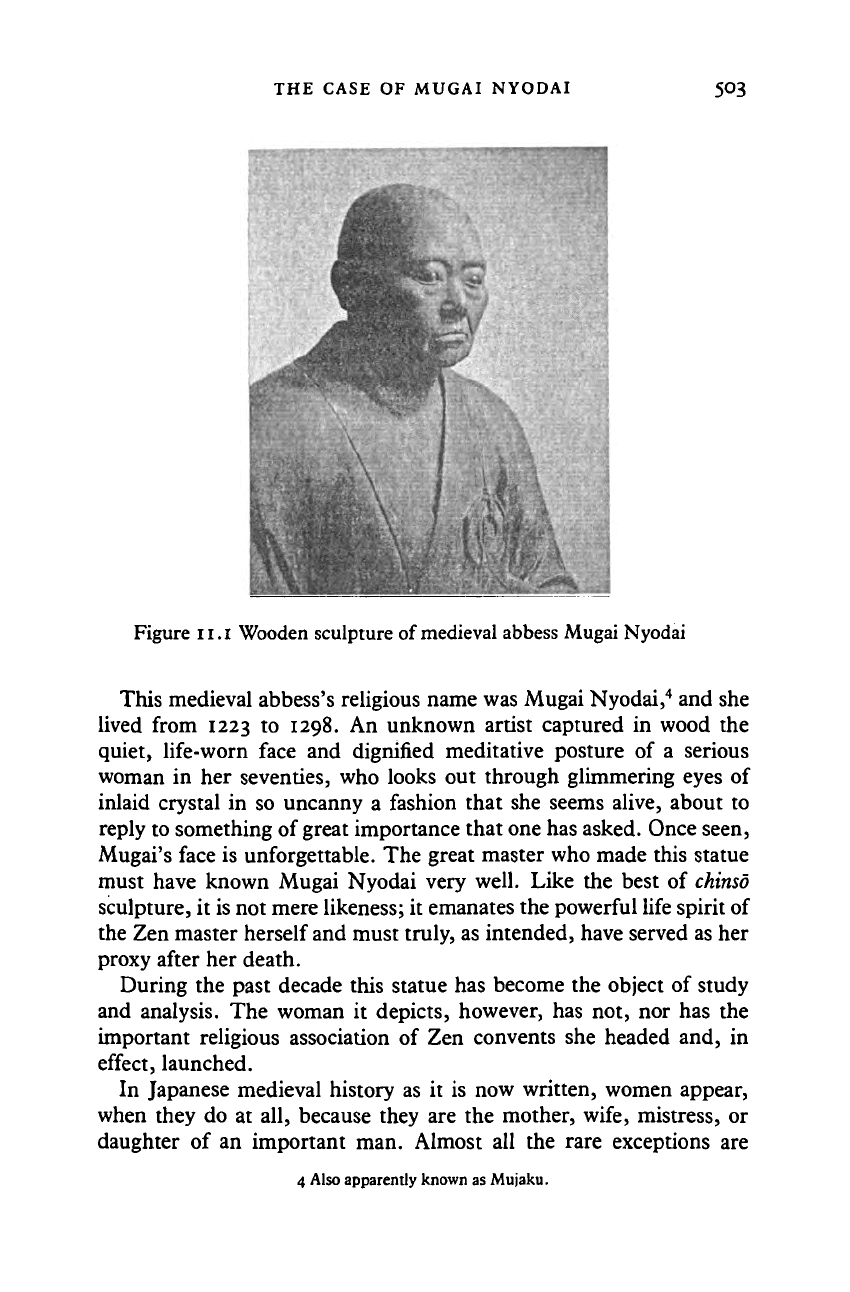

THE CASE OF MUGAI NYODAI

In 1976 Nishikawa Kyotaro published a book on the subject

ofchinso,

1

or what I shall term "proxy statues," a genre of sculpture devoted to

the realistic, three-dimensional portrayal of the seated figures of his-

torical Zen priests, whose function was to convey the essence of the

master of his disciples after his death. The wooden statues depicted

were largely similar-looking ecclesiastics in Buddhist robes with

shaved heads. But one, despite the uniform presentation, somehow

seemed different from the rest. Astonishingly, it was the figure of a

thirteenth-century female Zen master. No remnant of feminine culture

can be seen in her figure; with shaved head and Buddhist robes, she

looks almost identical to her male colleagues. Yet the flesh of the face

and shoulders is incontrovertibly matronly; it is indeed the portrait of

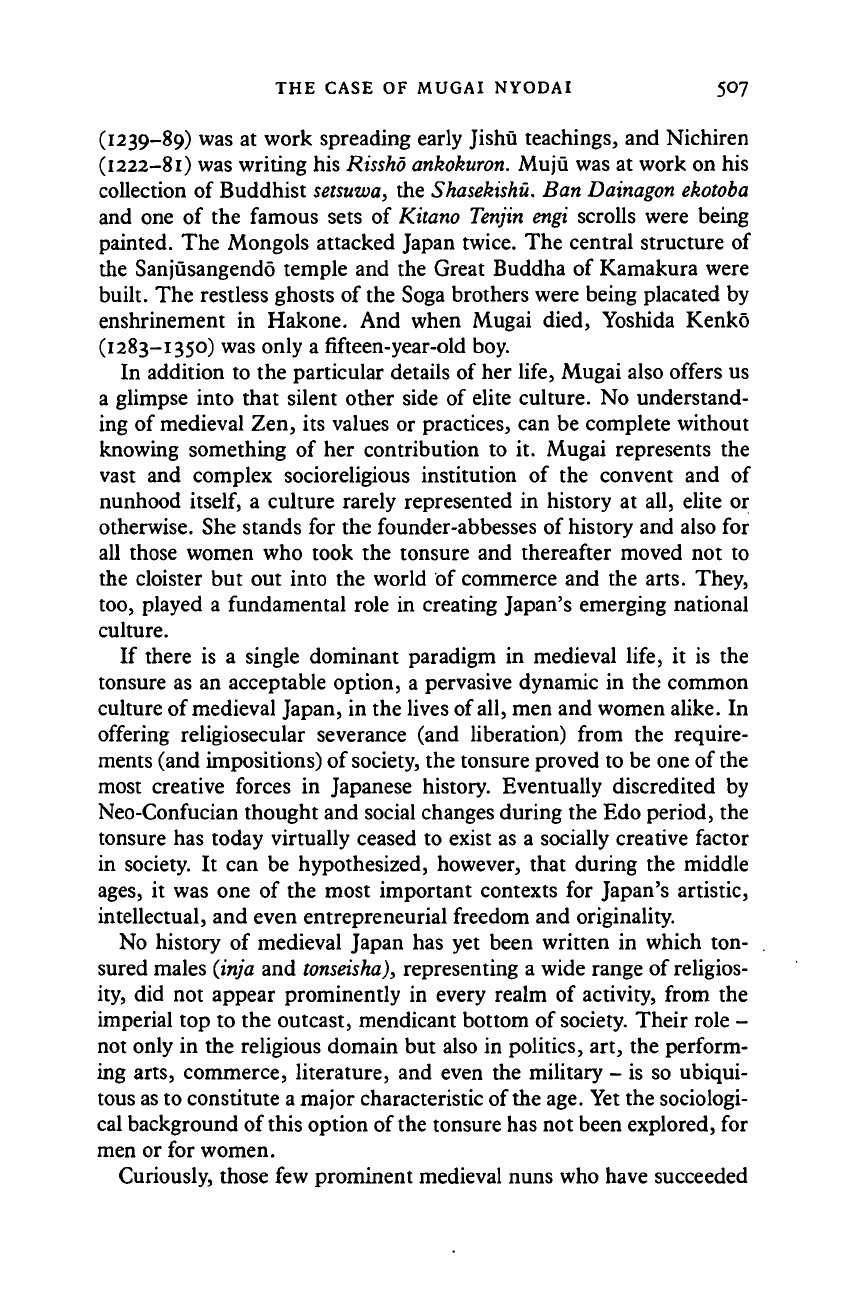

a woman (see Figure 11.1).

2 Toyoda Takeshi, "Tenkanki no shakai," in OtogizoM, vol. 13 of Zutsetsu Nihon no koten

(Tokyo: Shueisha, 1980), p. 196.

3 Nishikawa Kyotaro, Chinso

chokoku,

in Nikon no bijutsu, no. 123 (Tokyo: Shibundo, 1976).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CASE OF MUGAI NYODAI 503

Figure 11.1 Wooden sculpture of medieval abbess Mugai Nyodai

This medieval abbess's religious name was Mugai Nyodai,

4

and she

lived from 1223 to 1298. An unknown artist captured in wood the

quiet, life-worn face and dignified meditative posture of a serious

woman in her seventies, who looks out through glimmering eyes of

inlaid crystal in so uncanny a fashion that she seems alive, about to

reply to something of great importance that one has asked. Once seen,

Mugai's face is unforgettable. The great master who made this statue

must have known Mugai Nyodai very well. Like the best of

chinso

sculpture, it is not mere likeness; it emanates the powerful life spirit of

the Zen master herself and must truly, as intended, have served as her

proxy after her death.

During the past decade this statue has become the object of study

and analysis. The woman it depicts, however, has not, nor has the

important religious association of Zen convents she headed and, in

effect, launched.

In Japanese medieval history as it is now written, women appear,

when they do at all, because they are the mother, wife, mistress, or

daughter of an important man. Almost all the rare exceptions are

4 Also apparently known as Mujaku.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

504 THE OTHER SIDE OF CULTURE

women who have written outstanding literary works that somehow

have survived. Mugai Nyodai, however, represents a challenging case.

Here is a woman of superb accomplishments in the ecclesiastical

world, and yet no one seems certain just which "important man"

might have been her father or her husband. What were the facts of this

woman's life, and what was the nature of the institution she headed?

From this perspective, her life takes on an importance beyond the

historical; it has generic ramifications.

The tonsure was as widespread in female culture as it was in male

culture, and possibly more so, for even at that time, if they lived

through childbearing, women tended to outlive their husbands -

sometimes by a great many years when the occupational hazards of the

wars thinned out the male population. There were also a variety of

nunhoods, ranging from a status that permitted a spiritual life of

ascetic devotion, to a welfare system for the abused or impoverished,

to a disguise for prostitution. Indeed, just what was nunhood in medi-

eval society? And what was the institution of the convent? No one

knows. It is hard to find reliable information on even the lives of

eminent nuns.

The standard references on Japanese history and Buddhism reveal

the woeful state of current research on ecclesiastic women in Japan.

Each authority assigns to Mugai a different Hojo-connected father and

husband. Further inquiry reveals one husband to have been twenty-

five years her junior, another thirty-five years younger - unthinkable

liaisons for that time. Her alleged fathers, too, are incongruously in-

triguing, as one was born eight years after she was and another was

born when she was twenty-five!

5

Such neglect is not due to Mugai's failure to fulfill the traditional

qualifications for history. An extraordinary person from well-

connected bushi stock, born into the Adachi family, given the name

Chiyono when she was young, married into a branch of the Hojo clan,

highly educated in both Japanese and Chinese, Mugai was a woman to

be reckoned with. Owing to circumstances as yet unclear, in mid-life

she studied Zen under the Chinese priest Mugaku Sogen (also called

Bukko Kokushi, 1226-86), who had come to Japan in 1279 at the

invitation of the regent Hojo Tokimune to head the Kenchoji temple in

5 Nihon rekishi daijiien (Tokyo: Kawade shobo shinsha, 1956); Sanshu meiseki shi 21 and Fuso

keika shi 2, in Shinshu Kyoto

sosho,

vols. 2 and 9 (Kyoto: Kosaisha, 1967); Koji ruien, vol. 44

(Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1969); and Dai Nihon jiin soran (Tokyo: Meiji shuppansha,

1917).

As of this writing no published accounts concerning Mugai's family should be taken as

reliable. Even the most recent contain inherent inconsistencies and errors, and many problems

remain to be solved.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CASE OF MUGAI NYODAI 505

Kamakura. After Mugaku Sogen founded the Engakuji in 1282 and

began laying the groundwork for the establishment of Rinzai Zen in

Japan, Mugai continued as his proselyte. Before his death in 1286, he

recognized her as the heir to his teachings and gave her the character

mu from his own name. Mugai thus became the first woman in Japan

fully qualified not as a nun but as a Zen priest (Zen

so).

After her years under Mugaku Sogen, Mugai Nyodai founded, and

served as the abbess of, the Keiaiji temple and its sub temples in north-

ern Kyoto, which throughout the Muromachi period stood at the

pinnacle of

the

developing network of Zen convents known as the Niji

(Amadera) Gozan, or the Five-Mountain Convents Association, an

institution organized concurrently with the Gozan (five-mountain)

Monasteries established for male priests.

6

Mugai's Keiaiji headed the

Niji Gozan network, which in her day had more than fifteen

subtemples. In the generation after her death, the Five-Mountain

Convents expanded to include the Keiaiji, Tsugenji, Danrinji,

Gonenji, Erinji, and their subtemples in Kyoto, as well as five con-

vents in Kamakura: the Taiheiji, Tdkeiji, Kokuonji, Gohoji, and

Zemmyoji. Keiaiji, it is said, was burned down in the Onin War

during the mid-fifteenth century, at which time Mugai's

chinso

and

other relics were removed to one of Keiaiji's subtemples in Kyoto, the

Hoji-in (also known as Chiyonodera), where they remain today.

7

Mugai was born during a short but receptive time in Japanese his-

tory for the participation of women in official religious institutions.

Buddhism, like Christianity, has had a dismal history of discrimina-

tion against women. Theologically women were viewed as inherently

flawed, as both defiled and defiling; they were forbidden to enter even

the grounds of the major Buddhist centers of learning and worship,

such as Mount Hiei and Mount Koya, and they were also barred by

doctrine from attaining Buddhahood. Now suddenly, in Mugai's life-

time,

momentous and major changes were foot. All of the newly

founded and growing sects of reform Buddhism (Pure Land,

Nichiren, and Zen) were asserting that the old sects had erred and that

Buddha's compassion extended to the salvation of all sentient crea-

tures.

The statements of the Zen priest Dogen (1200-53), in particular,

were world-shaking. Indeed, Stanley Weinstein's fine studies of re-

6 See Martin Collcutt, Five Mountains: The Rinzai Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard East Asian Monographs no. 85, 1981). No research has yet been

published in any language on the Niji Gozan system of Zen convents.

7 A name taken from what is thought to have been her childhood name, Chiyono.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

506 THE OTHER SIDE OF CULTURE

form Buddhism reveal that Dogen, of all the new religious leaders,

was "by far the most uncompromising on asserting complete equality

between the sexes."

8

In his treatise Shobogenzo, Dogen describes the

new world into which Mugai was fortunate enough to be born:

When we speak of

the

wicked there are certainly men among them. When we

talk of noble persons, these surely include women. Learning the Law of

Buddha and achieving release from illusion have nothing to do with whether

one happens to be a man or a woman.

9

A nun who has attained the Way is entitled to receive the homage of

all

the

arhats, pratye&a-buddhas and bodhisattvas who would seek to learn the

Dharma from her. What is so sacred about the status of a man? . . . The four

elements that make up the human body are the same for a man as for a

woman. . . . You should not waste your time in futile discussions about the

superiority of one sex over another.

10

Zen was then virtually a new sect of Buddhism in Japan. Known

early to the Japanese, it made no lasting impression for centuries and

no inroads into Japanese religious life until Eisai (1141-1215) intro-

duced Rinzai teachings in 1191 and his student Dogen introduced

Soto thought in 1227, just four years after Mugai was born. Her life

was fundamentally changed by this new wave of social thought, and

the path she chose was one that affected the lives of thousands of other

women who joined the Five-Mountain Convents.

Mugai lived during a time when the foundations of modern Japa-

nese society and culture were taking shape. Women and men from

every stratum of society were taking part in its design. Studying

Mugai's life, then, illuminates this period from a different perspective

than has been available to us before.

Dogen went to China the same year that Mugai was born. While she

was still an infant, Shinran (1173-1262) had begun actively to propa-

gate the Jodo Shin faith. Dogen returned from China when Magai was

four and wrote his Shobogenzo when she was ten. The great courtier-

poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241) was still alive throughout her

teens,

and numerous famous waka-poetry collections appeared as she

grew up. In her adolescence, the Uji shui monogatari and Azutna

kagami were written, and 6m>a-priests were chanting narratives

around the country that recounted episodes from the cataclysmic

Gempei War of a half-century earlier. In Mugai's middle years, Ippen

8 Stanley Weinstein, "The Concept of Reformation in Japanese Buddhism," in Saburo Ota,

ed.,

Studies

in

Japanese Culture, vol. 2 (Tokyo: P.E.N. Club, 1973), p. 82.

9 Weinstein, "Concept of Reformation," p. 82, trans, from Shobogenzo, Iwanami bunko ed.

(Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1939), vol. I, p. 128.

10 Weinstein, "Concept," p. 82, trans, from Shobogenzo, vol. 1, p. 124.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CASE OF MUGAI NYODAI 507

(1239-89) was at work spreading early Jishu teachings, and Nichiren

(1222-81) was writing his Rissho ankokuron. Muju was at work on his

collection of Buddhist setsuwa, the Shasekishu. Ban Dainagon ekotoba

and one of the famous sets of Kitano Tenjin engi scrolls were being

painted. The Mongols attacked Japan twice. The central structure of

the Sanjusangendo temple and the Great Buddha of Kamakura were

built. The restless ghosts of the Soga brothers were being placated by

enshrinement in Hakone. And when Mugai died, Yoshida Kenko

(1283-1350) was only a fifteen-year-old boy.

In addition to the particular details of her life, Mugai also offers us

a glimpse into that silent other side of elite culture. No understand-

ing of medieval Zen, its values or practices, can be complete without

knowing something of her contribution to it. Mugai represents the

vast and complex socioreligious institution of the convent and of

nunhood

itself,

a culture rarely represented in history at all, elite or

otherwise. She stands for the founder-abbesses of history and also for

all those women who took the tonsure and thereafter moved not to

the cloister but out into the world of commerce and the arts. They,

too,

played a fundamental role in creating Japan's emerging national

culture.

If there is a single dominant paradigm in medieval life, it is the

tonsure as an acceptable option, a pervasive dynamic in the common

culture of medieval Japan, in the lives of

all,

men and women alike. In

offering religiosecular severance (and liberation) from the require-

ments (and impositions) of society, the tonsure proved to be one of the

most creative forces in Japanese history. Eventually discredited by

Neo-Confucian thought and social changes during the Edo period, the

tonsure has today virtually ceased to exist as a socially creative factor

in society. It can be hypothesized, however, that during the middle

ages,

it was one of the most important contexts for Japan's artistic,

intellectual, and even entrepreneurial freedom and originality.

No history of medieval Japan has yet been written in which ton-

sured males (inja and tonseisha), representing a wide range of religios-

ity, did not appear prominently in every realm of activity, from the

imperial top to the outcast, mendicant bottom of society. Their role -

not only in the religious domain but also in politics, art, the perform-

ing arts, commerce, literature, and even the military - is so ubiqui-

tous as to constitute a major characteristic of the age. Yet the sociologi-

cal background of this option of the tonsure has not been explored, for

men or for women.

Curiously, those few prominent medieval nuns who have succeeded

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

5O8 THE OTHER SIDE OF CULTURE

in attracting historians' attention were alive during Mugai's

years.

The

nun Eshin (i

182-

1270s),

the first official wife of a priest in Japan,

actively supported the work of her husband, Shinran, in his Jodo Shin

teachings. Both Lady Nijo (1258-1306?), the author of

Towazugatari,

and Abutsu (i233?-83?), the author of

Utatane no

ki and Izayoi nikki,

were traveling throughout Japan as nuns during Mugai's lifetime,

though they had taken the tonsure with considerably different aims

than did either Mugai Nyodai or Eshir. Both women wrote notable

autobiographies whose contents are self-absorbed and concerned to

varying degrees with literary ambition." Indeed, their work has been

of historical interest primarily because of its literary value; the reli-

gious consciousness they express is only elementary. Nijo's pilgrimage

appears to have been the traditional medieval tourist course; Abutsu's

tonsure, which took place in her late teens, was hardly a religious

decision, but an act of despair akin to suicide over a dying love affair.

During her brief stay in a convent, it was the man who had grown

indifferent to her who obsessed her thoughts. Nevertheless, neither

woman would probably have achieved what she did in her day had she

not taken the liberating step of choosing the tonsure.

It is troubling that although the lives of these two aristocratic

women have been studied, no one has yet examined their nunhood or

tried to explore its meaning in the context of medieval society.

Nunhood, after all, was not an elite pursuit. Nijo encountered several

nuns who had previously made their living as prostitutes; one was a

former brothel owner. If we are to believe the overwhelming statistical

evidence of medieval fiction, diaries, poetry, songs, paintings, and

drama, then nunhood must have been common in medieval life from

the top to the bottom of

society,

an acceptable alternative in the popu-

lar culture of medieval Japan.

Becoming a nun in childhood was rare, but taking the tonsure in

late middle age was common among all classes and geographical areas.

Indeed, when one was widowed, society expected it. Some widows

clearly "acquiesced" to nunhood, in Emile Durkheim's sense of the

word.

12

Widows' becoming nuns also had an important secular socio-

11 For English translations of these works, see Karen Brazell, trans., The

Confessions

of Lady

Nijo (New York: Anchor Books, 1973); and Edwin O. Reischauer, trans., "The Izayoi

Nikki," in Edwin O. Reischauer and Joseph K. Yamagiwa, eds.,

Translations

from Early

Japanese Literature (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1951), pp. 3-135. Donald

Keene recounts Abutsu's diary, Utatane no ki, written when she was about seventeen years

old,

in "Diaries of the Kamakura Period," Japanese Quarterly 32 (July-September 1985):

186-9.

12 Emile Durkheim, The Rules of

Sociological Method

(Glencoe, N.Y.: Free Press, 1950), p. 104.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008