The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CONCLUSION 299

of the decline of the shoen system during the Nambokucho period. As

a result of the conflict after the fall of the Kamakura bakufu, the civil

government lost its political viability. It lost the ability to guarantee

the scattered, hierarchical shiki rights of the shoen, and so the honke

shiki, the pinnacle of this structure, became untenable. At the same

time,

local powers focused their authority on a single, contiguous piece

of land and, in so doing, were transformed into kokujin ryoshu with

independent control over the area. The shugo increased their judicial

authority and land control while incorporating the kokujin and

jizatnurai into their vassal organization. The

shugo

developed a provin-

cial system based on a feudal lord-vassal power structure, namely, the

shugo

domainal system (ryogokusei).

The second stage proceeded from the political consolidation under

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu at the end of the fourteenth century until the

Onin War. During this period, the shoen system experienced a slight

respite from the buffeting forces when the Muromachi bakufu

adopted a protective policy toward the

shoen.

Despite this policy, the

maintenance of the shoen system depended on the ukeoi daikan system

and on the offices of the shugo, kokujin, and doso. In this period the

shoen proprietors lost their ability to administer the shoen indepen-

dently. Furthermore, this period was notable for the appearance of

agrarian protests supported by the development of the

so-mura

and the

social and economic growth of the kobyakusho class which further

spurred the fall of the shoen system.

The third stage in the decline of the shoen system was the period

of civil war in the sixteenth century. The domainal system of the

sengoku daimyo - the culmination of the kokujin ryoshu and shugo

ryogoku system - categorically suppressed the shoen. The kandaka

system established by the sengoku daimyo was premised on the supe-

riority of the daimyo's political rights throughout the domain. By

means of this system, the daimyo implemented a unified measure

for nengu and the correlation of chigyo to the amount of military

service owed by the retainer. As a result, the daimyo succeeded in

organizing the kokujin and jizamurai in their domains into a feudal

lord-vassal structure.

The

shoen

system passed through these three stages, but there were,

as mentioned, significant regional variations in the rate of decline.

Shoen continued to exist even into the sixteenth century in the Kinai

and neighboring provinces where noble and religious authority was

most firmly rooted. Although in decline, the shoen of those areas

resisted the onset of the daimyo domainal system of the Sengoku

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3OO THE DECLINE OF THE SHOEN SYSTEM

period. The death knell for these last surviving shoen was sounded by

the cadastral surveys conducted by Hideyoshi (Taiko kenchi).

Hideyoshi's surveys drew a curtain on the turbulence of the Sengoku

period. Between 1582 and 1598, Hideyoshi conducted cadastral surveys

throughout Japan. These surveys measured nengu and chigyo by a uni-

fied standard called kokudaka (an assessed base of

nengu

measured in

rice).

Along with the complete rejection of the collection of kajishi by

the cultivating class, the surveys eliminated the shoen as a unit of land

ownership.

75

Even the surviving

shoen

of the nobles and religious estab-

lishments in Yamashiro and Yamato provinces were eliminated. In ex-

change, their new holdings were assessed at a fixed amount of kokudaka

somewhat lower than the previous amount.

Under the Taiko kenchi, the village became the lowest locus of con-

trol throughout the country. The village unit existed widely under the

shoen system, but it was not the exclusive unit, as other administrative

units such as myo and go were also used. Hideyoshi's surveys com-

pletely rejected these other units and replaced them with the village

and its functional social value as a rural community as the building

block of control. As a result, the shoen was rejected as an element of

control. In the case of Tara-no-sho in Wakasa Province, a single village

community already existed on the shoen, which was more and more

often referred to as Tara village. The practice of designating an area by

the previous shoen name continued in some areas even into the Edo

period, but this was strictly a popular, unofficial practice.

Hideyoshi's cadastral surveys were inextricably linked to the separa-

tion of warriors and cultivators

{heino

bunri). Heino bunri made a sharp

distinction between warrior and peasant {hyakusho) status and re-

quired that all those of warrior status assemble at the daimyo's castle

town. This policy brought an end to the zaichi rydshu system, the

hallmark of medieval society. Persons who served as retainers, even

though originally of hyakusho status, were forced to choose either to

remain in the village as hyakusho or to leave the village and move to the

daimyo's castle town and become warriors. The separation of warrior

and cultivator made it possible to establish a permanently mobilized

army stationed at the castle and to assemble a ruling class based on

centralized power. The emperor, nobility, and religious establishments

were consequently pushed out of power, and at the same time, their

economic and social foundation, the shoen, was eradicated.

75 For a discussion of the Taiko kenchi, see Araki Moriaki, Taiko kenchi to kokudakasei (Tokyo:

Nihon hoso shuppan kyokai, 1969); and Miyagawa Mitsuru, Taiko kenchi ton (Tokyo:

Ochanomizu shobo, vol.

1,1959;

vol. 2, 1957; vol. 3, 1963).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER 7

THE MEDIEVAL PEASANT

Historians generally date the medieval period in Japanese history as

starting at the end of the twelfth century when the Kamakura bakufu

was established, marking the emerging dominance of warrior govern-

ment over aristocratic rule. In peasant history, however, the latter half

of the eleventh or early twelfth century, however, is a more appropriate

point of division between the ancient and medieval periods. The

shden

system of land control had extended throughout Japan around that

time,

bringing entirely new conditions for the peasants and making

them henceforth truly "medieval." The introduction and development

of the

shden

system had a much greater impact on the living conditions

of peasants in Japan than did the founding of the Kamakura bakufu

nearly a century later. The

shden

system, therefore, is of great signifi-

cance in peasant history and is the central defining characteristic of the

medieval period.

1

The momentous changes for the peasants brought about by the

shden system must be understood in the context of the earlier condi-

tions pertaining to the land of the

ritsuryo

system in the eighth century.

Under the ritsuryo system, the central government claimed ownership

of all land; cultivators were allotted paddies on an equitable basis; and

taxes were collected according to specific categories of goods; for exam-

ple,

grain, labor, and silk. But these conditions began to break down

rapidly early in the tenth century and had disintegrated entirely by the

time the

shden

system had spread throughout Japan in the late eleventh

and early twelfth centuries. Under the shden system, the peasants

exhibited characteristics different from those of the earlier ritsuryo

system. For this reason, the medieval peasant I describe in this chapter

can be regarded as simply the

shden

peasant.

Similar to the controversy among scholars concerning the beginning

i For a comprehensive discussion of the

shden

system, see Amino Yoshihiko, "Shden koryosei no

keisei to kozo," in Takeuchi Rizo, ed., Tochi seidoshi, vol. i (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan,

'973).

PP- 173-274; Nagahara Keiji, Shden (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1978); and Kudo Keiichi,

"Shoensei no tenkai," in Iwanami koza Nihon rekishi, vol. 5 (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1975),

pp.

251-98.

301

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

302 THE MEDIEVAL PEASANT

of the medieval period in Japan, the date marking the end of this period

is also debated. Political historians designate 1573 as the beginning of

the early modern period, the year Oda Nobunaga defeated Shogun

Ashikaga Yoshiaki and destroyed the Muromachi bakufu. By this time,

the

sengoku

daimyo had divided Japan

into

individual

domains,

but with

Nobunaga's victory over Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the unification process

began. Of more importance to the peasants, however, was Toyotomi

Hideyoshi, Nobunaga's successor, who undertook to unify the country.

In 1582, Hideyoshi ordered a national cadastral survey, the Taiko

kenchi.

2

This comprehensive system of land registration completely

revolutionized land administration and tenure practices in Japan and

swept away all previous systems of landholding. I contend that this

event and the changes it brought marked the end of the medieval period

and the beginning of the early modern period for the peasants in Japan.

Although most scholars of peasant history agree that the medieval

period began with the spread of the

shoen

system throughout Japan

and ended with the Taiko

kenchi,

it would be an oversimplification to

define the entire medieval period, spanning the early twelfth century

to 1582, solely in terms of the

shoen

system and its effect on peasant

life.

For nearly five centuries, until the fall of the Kamakura bakufu in

I

333J

tne

shoen system was remarkably stable. During the

Nambokucho period (1336-92), however, the

shoen

order began to

break down, and in the subsequent Muromachi and Sengoku periods,

territorial rule was established by a class of independent local over-

lords

(tyoshu)

who began by serving as jito (military estate stewards)

and

shoen

officials within the

shoen

system. At the same time, the

shugo

(provincial military governor) in each province consolidated their con-

trol as military and civil authorities over these local overlords. These

developments in territorial control culminated in the emergence of the

shugo

daimyo in the fifteenth century and the

sengoku

daimyo in the

following century. Therefore, the peasants of the latter half of the

medieval period - the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries -

are defined less by the

shoen

system than by the territorial authority

system built up by these local overlords. Agricultural productivity

increased dramatically in the second half of the medieval period, pro-

viding the economic foundation on which to base territorial rule. For

this reason, the study of the medieval peasant must consider, in addi-

tion to the

shoen

system and its effects on the peasant, the later system

2 For a more complete description of the Taiko kenchi, see Araki Moriaki, Taiko kenchi to

kokudakasei (Tokyo: Nihon hoso shuppankyokai, 1969).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STATUS DIFFERENCES AMONG PEASANTS 3O3

of territorial control, which took its most mature form as the daimyo

ryogoku

system of the Sengoku period.

Even in the early medieval period there were local overlords. They

were closely tied to the shoen system, however, as jito or officials.

Thus,

although there were clear distinctions between the authority

systems of the early and late medieval period, there was also continuity

in that a local overlord system existed throughout the entire period, if

at greatly different levels of development. The life of the peasants was

defined by the continuities and changes in the authority systems of the

medieval period.

Variations in medieval peasant life can be attributed not only to

these changes during the medieval period but to geographical location

as well. Agricultural productivity in the central Kinai area was consid-

erably higher than in the peripheral areas in eastern Japan and

Kyushu, implying a higher standard of living for the peasants of this

region. Proximity to large cities, Kyoto and Nara in particular, also

played a role, in that residing near these cities enriched the lives of the

peasants both economically and culturally. The life of the peasants in

the Kinai region, therefore, differed dramatically from that of those in

eastern Japan or Kyushu.

With these variations in mind, I shall portray the medieval peasants

mainly as they existed under the shoen system in the central Kinai

region. The development of the shoen system in this region was stable

and, therefore, the most appropriate setting for a study of peasant

activities. I shall also consider regional differences within the peasant

class,

as well as changes during the medieval period.

STATUS DIFFERENCES AMONG PEASANTS IN THE SHOEN

SYSTEM

The shoen as a place to live

The first

shoen

emerged in the mid-eighth century, chiefly in the form

of newly opened lands that aristocratic families and the religious estab-

lishment developed with the assistance of the state. A grain tax on

these lands had to be submitted to the central government, but posses-

sion of the land itself was recognized as a private right. By contrast,

the shoen that spread throughout Japan in the eleventh and twelfth

centuries - the so-called commended shoen - were lands opened by

prominent local families who then commended them to aristocrats or

great religious establishments. It was common practice not only to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

304 THE MEDIEVAL PEASANT

commend such newly opened lands but also to divide up and absorb

into the

shoen

the adjacent vast holdings of

the

provincial office - land

still subject to public taxation. Therefore, both cultivated fields and

uplands and peasant settlements were part of the commended

shorn,

creating a contained, comprehensive environment for daily life. The

well-known Tara-no-sho of Wakasa Province under the Toji's propri-

etorship was located in a mountainous area and included thirty-two

cho of cultivated land, uplands, and a fairly contained community.

3

Ota

shoen,

a Koyasan holding in Bingo Province, included the eastern

half of Sera District and comprised six hundred

cho

of paddy land,

over ten communities, and extensive uplands.

4

Although the early

shoen

were simply privately owned cultivated fields, by the eleventh

and twelfth centuries, commended

shoen

constituted an all-inclusive

setting for medieval peasant life.

In nearly all cases,

shoen

proprietors were high-ranking aristocrats

or representatives of powerful temples and shrines in Kyoto or Nara.

These proprietors held rights to numerous

shoen

scattered throughout

Japan and collected taxes from them with which to support them-

selves. Taxes took the form of rice

(nengu)

and miscellaneous dues in

the form of nonrice products and labor

(zokuji).

The actual administra-

tion of individual

shoen

was left to local

shoen

officials. Most local

shoen

officials were members of prominent local families who owned their

own land and often had held the rank of subdistrict head on the lands

of the provincial office before the establishment of

the

shoen.

Although

they often commended their privately held land to aristocrats or reli-

gious establishments, these local officials converted into

shoen

the land

of the provincial office on which they held official posts, and they

themselves became

shoen

managers responsible for administering

shoen

affairs and consolidated their power in the area. Shoen were thus

established within the local power structure and, through high-level

aristocratic or religious patronage, avoided taxation by the provincial

office.

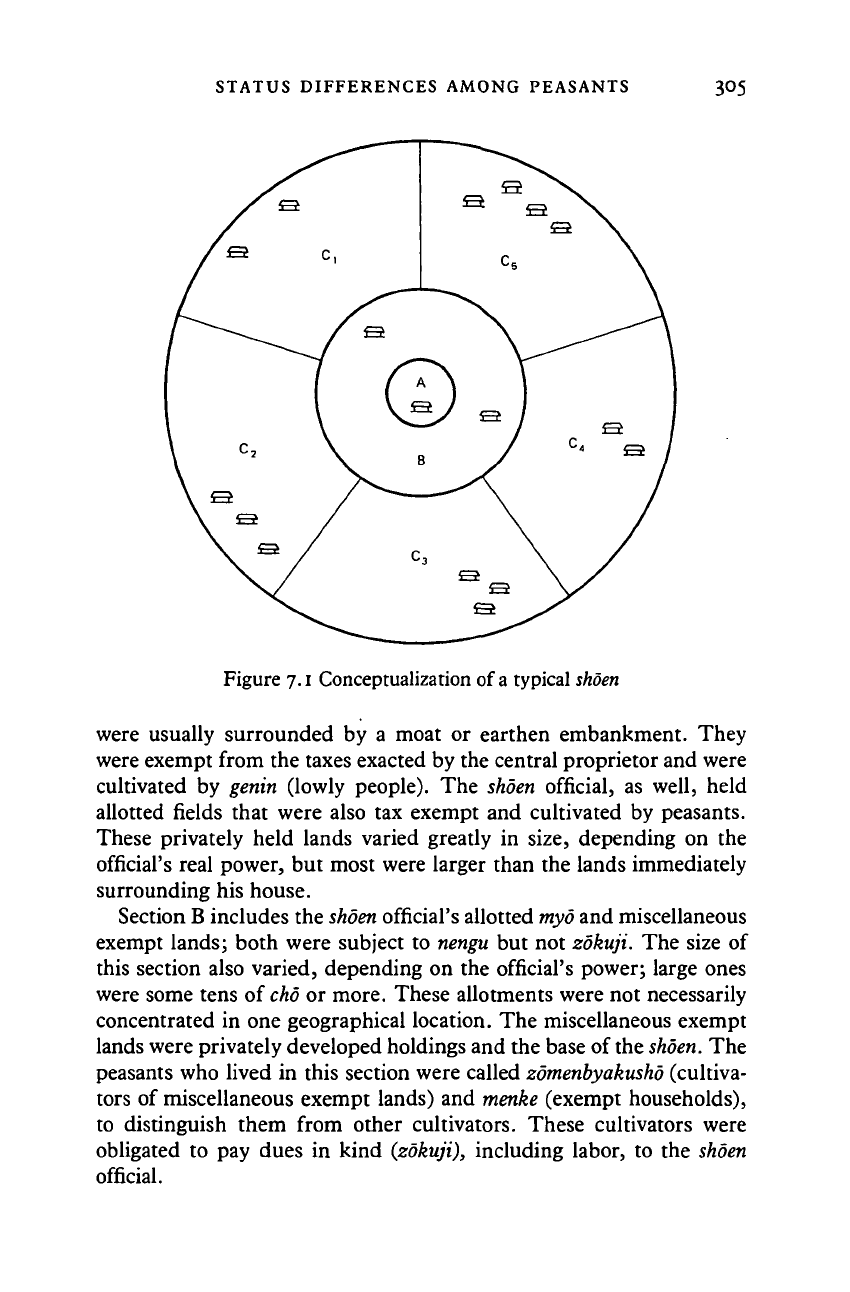

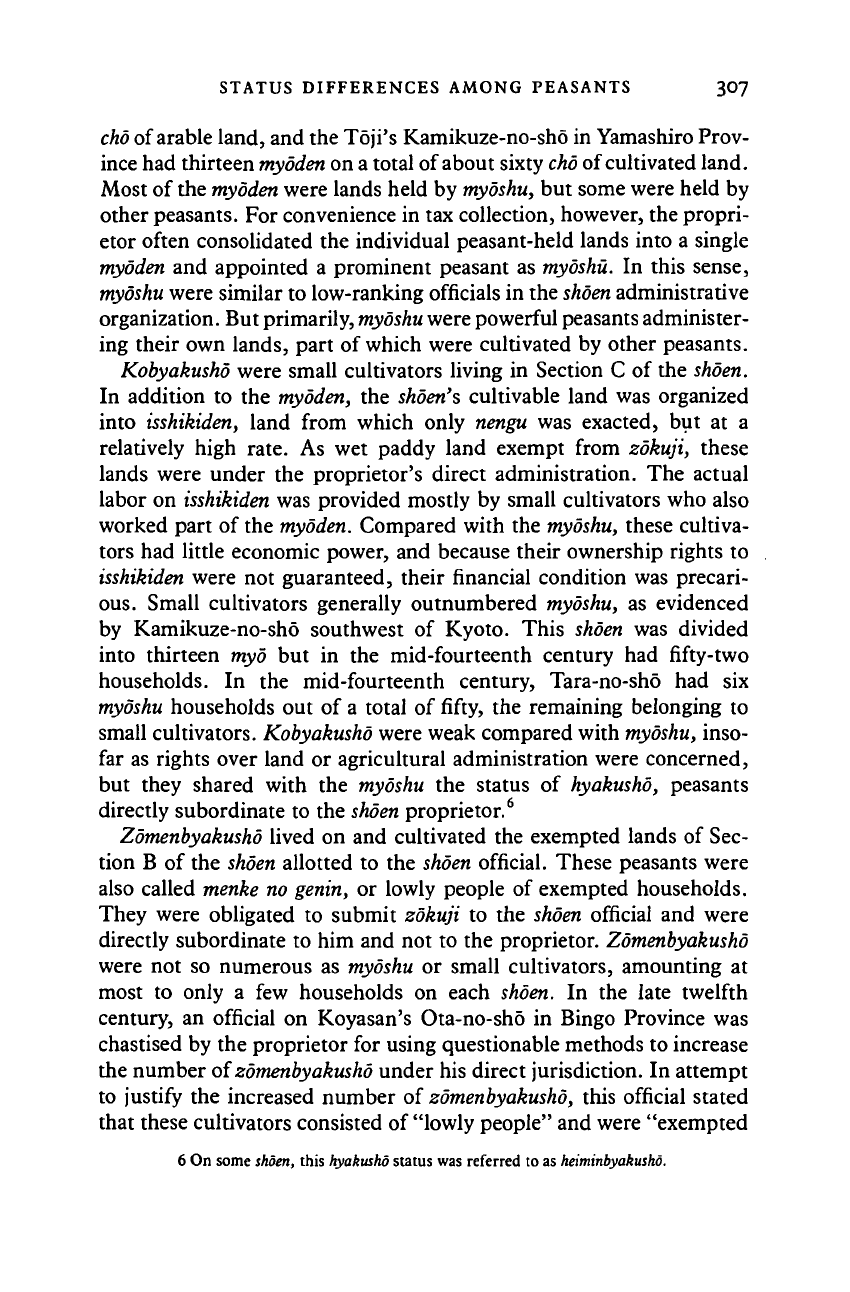

The central layout of a typical

shoen

is represented by concentric

circles in Figure

7.1.

Section

A

includes the house and the land imme-

diately surrounding (usually two or three

cho)

belonging to the local

shoen

official. These immediate lands included dry and wet fields and

3 For more information on Tara-no-sho, see Amino Yoshihiko, Chiisei

shoen no

yoso (Tokyo:

Tachibana shobo, 1966); and Kozo Yamamura, "Tara in Transition: A Study of

a

Kamakura

Shoen," Journal of Japanese

Studies

7 (Summer 1981): 349-91-

4 For more information on Ota-no-sho, see Kawane Yoshihira, "Heian makki no zaichi

ryoshusei ni tsuite," in Chiisei

hokensei

seirilsu shiron (Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai,

1970.

PP- 121-52.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STATUS DIFFERENCES AMONG PEASANTS 305

Figure 7.1 Conceptualization of a typical

shoen

were usually surrounded by a moat or earthen embankment. They

were exempt from the taxes exacted by the central proprietor and were

cultivated by genin (lowly people). The shoen official, as well, held

allotted fields that were also tax exempt and cultivated by peasants.

These privately held lands varied greatly in size, depending on the

official's real power, but most were larger than the lands immediately

surrounding his house.

Section B includes the

shoen

official's allotted myo and miscellaneous

exempt lands; both were subject to nengu but not zokuji. The size of

this section also varied, depending on the official's power; large ones

were some tens of

cho

or more. These allotments were not necessarily

concentrated in one geographical location. The miscellaneous exempt

lands were privately developed holdings and the base of the

shoen.

The

peasants who lived in this section were called zomenbyakusho (cultiva-

tors of miscellaneous exempt lands) and menke (exempt households),

to distinguish them from other cultivators. These cultivators were

obligated to pay dues in kind {zokuji), including labor, to the shoen

official.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

306 THE MEDIEVAL PEASANT

Section C comprises the core of the

shoen.

Originally part of the

public lands of the provincial office before the establishment of the

shoen,

these lands were brought under the direct control of the

shoen

proprietor. This section was usually divided into one to

five

communi-

ties (denoted C, through

C

5

in Figure

7.1).

The peasants living on these

lands were required to submit both

nengu

and zokuji to the

shoen

proprietor. Although they were not privately subordinate to the local

official but, rather, directly under the control of the

shoen

proprietor, it

was within the local official's authority to oversee the land and peas-

ants of Section C.

The

shoen

was home not only to the local official and peasants but

also to the artisans, craftsmen, and merchants who submitted their

commodities as taxes. Grant lands were set aside for these people, and

each plot was designated by function; for example, pottery, leather

goods, carpentry, metalwork, and boat transportation. The craftsmen

supported by these lands did not necessarily live on the

shoen

but

might live elsewhere and produce goods for the

shoen

in return for

income from these lands. Markets served as places of exchange on the

shoen

and on large

shoen

were held on prescribed days each month.

Through these grant lands and markets, the

shoen

acquired the com-

modities it did not produce. It is clear that shoen were not

self-

sufficient and that the division of labor was quite advanced.

5

Status subdivisions of the

peasantry

The peasants living on

the shoen

were divided into subgroups based

on a

complicated status system. These subgroups included

myshu,

kobya-

kusho,

zomenbyakusho,

tnoto, and

genin,

each indicating the group's

relative degree of freedom or subordination. These status levels re-

flected the great economic variation within the peasant class and the

various rights of the peasants and the duties they owed to the

shoen

proprietor and local official.

Myoshu

were powerful peasants

who

held much of the cultivated land

in Section C of the

shoen.

The proprietor divided this land into

myoden

(the basic unit of land on which the yearly tax

was

calculated, also called

hyakushomyo),

consisting of one or two

cho

or sometimes more. The

myoshu

had to submit a tax on each

myoden.

For example, the Toji's

Tara-no-sho in Wakasa Province had six

myoden

on

a

total of thirty-two

5 Concerning the problems surrounding markets and craftsmen on shoen, see Sasaki Ginya,

Shoen no shogyo (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1964).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

STATUS DIFFERENCES AMONG PEASANTS 307

cho

of arable land, and the Toji's Kamikuze-no-sho in Yamashiro Prov-

ince had thirteen

myoden

on a total of about sixty

cho

of cultivated land.

Most of the myoden were lands held by myoshu, but some were held by

other peasants. For convenience in tax collection, however, the propri-

etor often consolidated the individual peasant-held lands into a single

myoden and appointed a prominent peasant as myoshu. In this sense,

myoshu

were similar to low-ranking officials in the

shoen

administrative

organization. But primarily,

myoshu

were powerful peasants administer-

ing their own lands, part of which were cultivated by other peasants.

Kobyakusho were small cultivators living in Section C of the shoen.

In addition to the myoden, the shoen's cultivable land was organized

into isshikiden, land from which only nengu was exacted, but at a

relatively high rate. As wet paddy land exempt from zokuji, these

lands were under the proprietor's direct administration. The actual

labor on isshikiden was provided mostly by small cultivators who also

worked part of the myoden. Compared with the myoshu, these cultiva-

tors had little economic power, and because their ownership rights to

isshikiden were not guaranteed, their financial condition was precari-

ous.

Small cultivators generally outnumbered myoshu, as evidenced

by Kamikuze-no-sho southwest of Kyoto. This shoen was divided

into thirteen myo but in the mid-fourteenth century had fifty-two

households. In the mid-fourteenth century, Tara-no-sho had six

myoshu households out of a total of fifty, the remaining belonging to

small cultivators. Kobyakusho were weak compared with myoshu, inso-

far as rights over land or agricultural administration were concerned,

but they shared with the myoshu the status of hyakusho, peasants

directly subordinate to the shoen proprietor.

6

Zomenbyakusho lived on and cultivated the exempted lands of Sec-

tion B of the shoen allotted to the shoen official. These peasants were

also called menke no genin, or lowly people of exempted households.

They were obligated to submit zokuji to the shoen official and were

directly subordinate to him and not to the proprietor. Zomenbyakusho

were not so numerous as myoshu or small cultivators, amounting at

most to only a few households on each shoen. In the late twelfth

century, an official on Koyasan's Ota-no-sho in Bingo Province was

chastised by the proprietor for using questionable methods to increase

the number of

zomenbyakusho

under his direct jurisdiction. In attempt

to justify the increased number of zomenbyakusho, this official stated

that these cultivators consisted of "lowly people" and were "exempted

6 On some

shoen,

this hyakusho status was referred to as heiminbyakusho.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

308 THE MEDIEVAL PEASANT

households for free use, morning and night." In other words, the

official freely imposed taxes in goods and labor on them and consid-

ered them his own personal subordinates. Ordinarily, peasants of ex-

empted households could be used by the

skden

official as personal

subordinates only with the proprietor's permission. Thus,

genin

rather

than

hyakusho

best expresses the status of such peasants.

The peasants' subordinate character was especially evident in pe-

ripheral areas in eastern Japan and Kyushu. In these remote areas,

powerful peasants did not become

myoshu.

Instead, the higher-ranking

local

shoen

official designated as one

myo,

the area over which his own

control extended, and himself became the

myoshu.

In such cases the

myo

- the land unit under

myoshu

control - was subject to taxation

(nengu)

but was exempt from zokuji. The zokuji collected from peas-

ants living on the myo was kept by the

shoen

official

himself.

In other

words, for the

myoshu,

the myo was entirely tax exempt. In that re-

spect, the peasants living on the myo were strongly and personally

subordinate to the myoshu. This type of myo is distinct from

hyakushomyo

or proprietor myo, from which zokuji was submitted to

the proprietor. The peasants' subordination to local officials in periph-

eral areas was widespread, and proprietors unable to oversee adminis-

tration directly had no choice but to recognize that fact.

7

Myoshu,

kobyakusho,

zomenbyakusho

and

menke no genin

differed in

degree of administrative control and subordination, but all were

clearly sedentary peasants. By contrast, the fourth level of peasant, the

mow, were transients whose relations with the ruling class were not

clearly defined. Mow did not necessarily remain on any one

shoen;

those who did were unusual. In documents concerning Tara-no-sho

there is a reference to "a

mow

who arrived yesterday or today," imply-

ing that he had drifted in from another place or had not lived there for

long.

8

The

mow

had probably settled on a

shoen

at one time, living in a

hut, developing a bit of wasteland, and making ends meet by working

for a well-to-do peasant family. Such mow were most likely disdained

by the sedentary peasants. For example, on Tara-no-sho, a mow was

arraigned by the jito for taking in a beggar who had wandered into the

shoen

and stolen from the residents.

9

From this it can be surmised that

mow

were similar to beggars and were similarly despised.

7 For more information on the myo of remote areas, see Nagahara Keiji, Nihon hokensei

seiritsu

katei no kenkyu (Tokyo: Iwanamishoten, 1961), pp. 243-62.

8 Amino, Chusei

shoen

noyoso, pp. 76-79.

9 Beggars (kojiki) were a despised group in medieval Japan. See Nagahara Keiji, "Fuyu na

kojiki," in Nihon chusei shakai kozo no kenkyu (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1973), pp.

280-3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008