The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS 833

matter

to

each

of the 36

sections

of

National government, Directorate

of

Statistics,

Chung-hua

min-kuo t'ung-chi t'i-yao,

193j

(Statistical abstract

of the

Republic

of

China, 1935) includes useful descriptions

of

most

of

the statistical

publications

of

republican China.

Yen

Chung-p'ing, comp.

Chung-kuo

chin-tai

ching-chi

t'ung-chi tzu-liao

hsuan-chi

(Statistical materials

on

modern Chinese

economic history) draws

on a

wide range

of

sources which are carefully noted

and

- in

spite

of

its tendentious arrangement

and

commentaries,

not to

speak

of the compiler's apparent innocence about

'the

index number problem'

- is

of substantial value. Other collections

of

source materials

and

monographic

works are cited

in the

footnotes

to

chapter

1.

It

is

under these handicaps that

the

Chinese economy

in the

period

of the

republic must

be

surveyed. That

so

much

of

the macroeconomic description

included

in

this chapter hangs

on

what are, after all, only intelligent guesses

for

1933 makes

it

admittedly

a

hostage

to

fortune. Chinese domestic materials,

inadequate

as

they are, have

not yet

been fully exploited,

and

careful

use of

studies

of

the twentieth-century Chinese economy

by

such Japanese agencies

as the South Manchurian Railway will probably show them

to

contribute more

than we have seemed

to

credit them with.

Caveat

lector.

3.

THE

FOREIGN PRESENCE

IN

CHINA

Westel

W.

Willoughby,

Foreign

rights and

interests

in

China

(2nd edn

1927;

2

vols.)

is a

useful, although excessively legalistic, introduction

to

this whole

subject.

It

was well translated

by

Wang Shao-fang

as

Wai-jen

tsai Hua

t'e-ch'uan

ho

li-i, Peking: San-lien, 1957.

The many faces

of

the foreigner

in

China

in the

early twentieth century

are

reflected

in

substantial detail

in the

published

and

unpublished diplomatic

correspondence

and

consular records

of

each

of the

principal treaty powers.

Microfilm copies

of

the British, Japanese and American diplomatic archives

for

these years

are

available

in

major research libraries.

The

Chinese side

of the

diplomatic story may

be

pursued

in

that part

of

the archives

of

the Wai-chiao

pu (Ministry

of

Foreign Affairs) which

is in the

possession

of

the Institute

of

Modern History, Academia Sinica, Taipei.

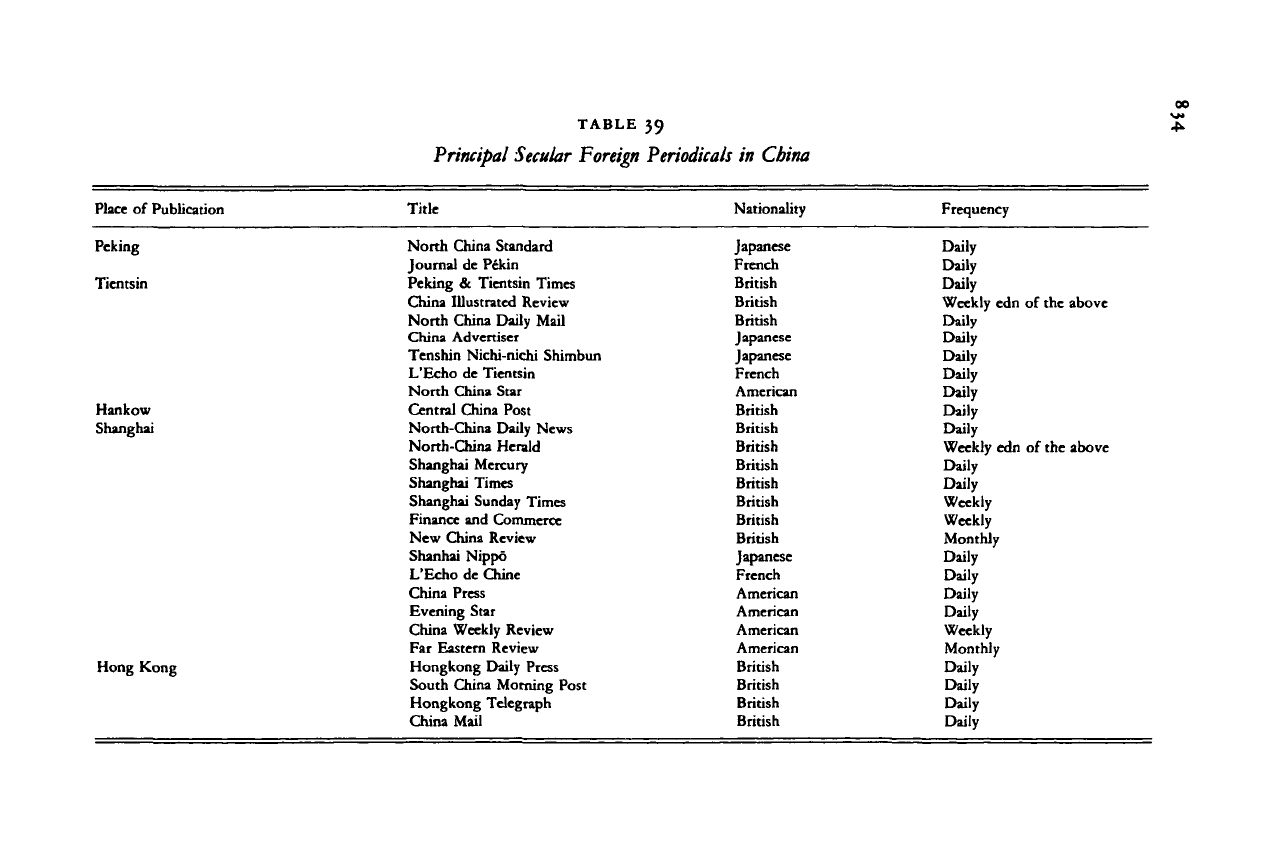

Eighty

or

ninety foreign-owned newspapers

and

periodicals circulated

in

China

in the

second decade

of the

century. Some

of

these were missionary

newsletters and journals,

in

Chinese

or

a foreign language. The principal secular

publications

as of

approximately

1920 at the

major ports

and

Peking,

but

excluding Manchuria, are listed below. This foreign press provides an important

supplement

to

the diplomatic record.

The immense literature on Christian missions in China was naturally produced

mainly

by the

missionaries themselves.

It

reflects their viewpoint. Clayton

H.

Chu, American missionaries

in

China: books, articles, and pamphlets extracted from

the

subject catalogue

of

the Missionary Research Library lists 7,000 items arranged

by

a detailed subject classification and,

its

title notwithstanding,

is not

limited

to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TABLE 39

Principal

Secular Foreign Periodicals

in China

00

-p.

Place of Publication

Title Nationality Frequency

Peking

Tientsin

Hankow

Shanghai

Hong Kong

North China Standard

Journal de Pekin

Peking & Tientsin Times

China Illustrated Review

North China Daily Mail

China Advertiser

Tenshin Nichi-nichi Shimbun

L'Echo

de Tientsin

North China Star

Central China Post

North-China Daily News

North-China Herald

Shanghai Mercury

Shanghai Times

Shanghai Sunday Times

Finance and Commerce

New China Review

Shanhai Nippd

L'Echo

de Chine

China Press

Evening Star

China Weekly Review

Far Eastern Review

Hongkong Daily Press

South China Morning Post

Hongkong Telegraph

China Mail

Japanese

French

British

British

British

Japanese

Japanese

French

American

British

British

British

British

British

British

British

British

Japanese

French

American

American

American

American

British

British

British

British

Daily

Daily

Daily

Weekly edn of the above

Daily

Daily

Daily

Daily

Daily

Daily

Daily

Weekly edn of the above

Daily

Daily

Weekly

Weekly

Monthly

Daily

Daily

Daily

Daily

Weekly

Monthly

Daily

Daily

Daily

Daily

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS 835

American missions. Although first published in 1929, Kenneth Scott Latourette,

A

history

of

Christian missions in China

remains a good starting place. The principal

Protestant journal published in China was

The Chinese Recorder

(Shanghai, 1867-

1941).

The

China Missions

Year

Book,

1910-25, continued as The

China

Christian

Year Book (1926-40), provides annual assessments of all aspects of Church

endeavour. Recent studies of twentieth-century missionary activities include

Paul A. Varg,

Missionaries,

Chinese,

and

diplomats:

the American Protestant missionary

movement

in China, 1890-19 j

2;

John K. Fairbank, ed. The

missionary enterprise

in

China and

America; Jessie Gregory Lutz,

China and the Christian

colleges,

18

jo-

19jo;

Shirley Garrett, Social

reformers

in urban China: the

Chinese

Y.M.C.A.,

189J-1926; James C. Thomson, Jr. While

China faced

West: American

reformers

in Nationalist China,

1928-}-/;

and Philip West,

Yenching University

and Sino-

Western

relations,

1916-/2. For the development of independent and indigenous

church movements among Chinese Protestant Christians, see Yamamoto

Sumiko,

Chugoku Kiristokyoshi

kenkyu (Studies on the history of Christianity in

China).

On the foreign role in the Maritime Customs, see Stanley F. Wright, China's

customs revenue since the Revolution

of if n, and Stanley F. Wright,

China's struggle

for tariff

autonomy:

1843-1938. Sir Robert Hart, who epitomized - and ran -

the Customs for four decades is revealed in Stanley F. Wright, Hart and the

Chinese

customs,

and John King Fairbank, Katherine Bruner, et a/., eds. The

I.G.

in

Peking:

letters

of Robert Hart,

Chinese Maritime

Customs,

1868-1907.

S.

A. M.

Adshead, The

modernization

of

the Chinese

Salt Administration, 1900-20, analyses

the role of Sir Richard Dane in the salt gabelle. The series Ti-kuo chu-iyii

Chung-

kuo

hai-kuan

(Imperialism and the Chinese Maritime Customs), of which I have

seen 10 volumes published in Peking by K'o-hsueh ch'u-pan-she between 1957

and 1962, reprints important documents translated from the Customs archives,

but has not included twentieth-century materials except in Vol. 10 on the hand-

ling of the Boxer indemnity payments during the republic.

Non-ideological treatment of the foreign economic role in twentieth-century

China is scarce. For basic data, see Carl F. Remer,

Foreign trade

of China; Carl

F.

Remer,

Foreign investments

in

China;

Yu-Kwei Cheng,

Foreign trade

and

indus-

trial

development

of

China;

and Chi-ming Hou,

Foreign investment

and

economic

development in

China,

1840-1937. Robert F. Dernberger, 'The role of the foreigner

in China's economic development, 1840-1949', in Dwight H. Perkins, ed.

China's modern economy

in

historical

perspective,

19-47, concludes that the foreign

sector 'clearly made a positive direct contribution to the Chinese domestic

economy'.

4.

THE ERA OF YUAN SHIH-K'AI

The first four or five years of the Republic of China, which comprehended

Yuan Shih-k'ai's presidency and separated the 1911 Revolution from the onset

of warlordism, have only rarely been taken by researchers and compilers as

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

836 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS

a unit. The great bulk of relevant collection and comment has come as a by-

product of interest in the 1911 Revolution. Scholarly attention rapidly tapers

off with the Ch'ing abdication and usually ceases entirely with the defeat of Sun

Yat-sen's group in the summer of 1913. This limitation applies to the great

documentary collections that have so stimulated studies of the republican

revolution: Peking's eight volumes of

Hsin-hai'

ko-ming

(The 1911 Revolution);

and the relevant volumes in the series

Chung-hua

min-kuo k'ai-kuo

wu-shih-nien

wen-hsien

(A documentary collection in celebration of the

5

oth anniversary of

the founding of the Republic of

China),

especially pt II, vols. 3-5, under the sub-

title of

Ko-sheng

kuang-fu (Restoration [to Chinese rule] in the provinces),

sponsored by the Kuomintang Archives in Taipei and others. Some memoirs

in Hsin-hai

ko-ming

hui-i-lu (Memoirs of the 1911 Revolution) carry on into the

early republic, but usually not far. The period has been better, though still

sparsely, served by the documentary series that serve the whole modern period,

or at least the first half of the twentieth century: from Taipei,

Ko-ming wen-hsien

(Documents of the revolution), and from Peking,

Chin-tai-shih tzu-liao

(Materials

on modern history). This tendency to concentrate on the 1911 Revolution while

neglecting the aftermath has had the effect of insuring the continuing value of

some older collections, notably Pai Chiao, Yuan Shih-k'ai yu

Chung-hua

min-kuo

(Yuan Shih-k'ai and the Republic of China), issued in 1936, as well as the more

recent Shen Yun-lung, comp. Yuan Shih-k'ai

shih-liao hui-pien

(Compendium of

sources on Yuan Shih-k'ai). The prospect of an expansion of published ma-

terials impends, as the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Peking proceeds

with ambitious plans to document and narrate the history of the Republic of

China.

General views of the period were for a long time dominated by writings

based on contemporary newspapers and anecdotes. The central theme has been

the obloquy of Yuan Shih-k'ai and his warlord progeny. The ablest represen-

tative of this tradition has perhaps been T'ao Ch'ii-yin, especially his

Pei-yang

chun-fa

t'ung-chih

shih-ch'i shih-hua

(Historical tales about the period of rule by

the Peiyang warlords), in six volumes (1957). This situation - an orthodoxy

only thinly buttressed by research - presented obvious temptations to any

historian out to reverse judgments. The challenge has been recognized in recent

years,

but no one has seen fit to attempt a full reversal of interpretation. In the

last section of a biography, Jerome Ch'en, Yuan Shih-k'ai, 18j9-1916 (rev. edn

1972),

offers a textured account of Yuan as a creature of his times. Edward

Friedman follows some of Yuan's revolutionary opponents through these

years in Backward toward revolution: the Chinese Revolutionary Party (1974). He

complicates our picture of Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary impulses without di-

minishing the justness of Sun's opposition. In

The presidency

of Yuan Shih-k'ai:

liberalism and dictatorship in early Republican China (1977), Ernest P. Young at-

tempts to analyse the presidency's policies apart from private motives and in

terms of new constellations of issues and political groups but finds the policies

deficient and, often enough, pernicious. The president of the first years of the

republic still lacks his champion.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS 837

Close attention to secondary figures has led to a more refined understanding

of the period. Liang Ch'i-ch'ao presents the most conspicuous opportunity in

this respect, since he was strategically placed and left a voluminous record,

including an unparalleled set of letters collected by Ting Wen-chiang as noted

above. Chang P'eng-yuan has been developing these possibilities: Liang Ch'i-

ch'ao

yii min-kuo

cheng-chih

(Liang Ch'i-ch'ao and republican politics). Biogra-

phies of Huang Hsing by Hsueh Chiin-tu and of Sung Chiao-jen by K. S. Liew

are helpful. Foreign advisers played some part in the dramatic events of Yuan's

presidency. The abundant papers of one, George Ernest Morrison, have been

selectively published for these years: The

correspondence

of G. E.

Morrison,

vol.

2,

1912-20, edited by Lo Hui-min.

The social and economic history of the early republic has to be patched

together in the first instance from various local or provincial studies centred on

the preceding revolution: see the publications of Mark Elvin, Joseph W.

Esherick, Mary Backus Rankin and Edward Rhoads. A discussion of the eco-

nomic policies of Yuan's regime occurs in Kikuchi Takaharu,

Chugoku

minzoku

undo

no kihon kozo - taigai boikotto no kenkyu (Basic structure of the Chinese

national movement - a study of anti-foreign boycotts). Articles on early re-

publican economic programmes, local peasant struggles, and the emerging

women's movement appear in major Japanese scholarly compendia: Chugoku

kindaika no shakai kozo: Shingai kakumei no shiteki ichi (The social framework

of China's modernization: the historical position of the 1911 Revolution);

Kirtdai Chugoku noson shakaishi

kenkyu (Studies on modern Chinese rural social

history); and Onogawa Hidemi and Shimada Kenji, eds. Shingai kakumei no

kenkyu (Studies on the 1911 Revolution). Philip Richard Billingsley's 1974

Ph.D.

dissertation at the University of Leeds, 'Banditry in China, 1911 to 1928,

with particular reference to Henan province', treats White Wolf's bandit group

of the early republic.

Foreign relations have been more systematically served by scholars, although

arguments about the domestic ramifications are hardly settled. The diplomacy

of the Reorganization Loan has been given detailed examination by P'u Yu-shu,

in an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Michigan of 1951,

'The Consortium reorganization loan to China, 1911-14; an episode in pre-war

diplomacy and international finance'. British relations and the intrigue over

Tibet are analysed in: Alastair Lamb, The

McMahon

line:

a

study

in the

relations

between

India,

China and

Tibet,

1904

to 1914; and Parshotam Mehra,

The McMahon

line and

after:

a study of

the triangular contest

on India's

northeastern frontier between

Britain,

China

and Tibet, 1904-47. The other critical relationship in these years

was with Japan. The literature is large. Among the book-length studies, these

are noteworthy: Li Yu-shu,

Chung-Jih erh-shih-i-t'iao

chiao-she,

I (Sino-Japanese

negotiations over the Twenty-one Demands, vol. I); Madeleine Chi, China

diplomacy,

1914-18; and Usui Katsumi, Nihon to

Chugoku

- Taisho jidai (Japan

and China: the Taisho period). The focus is naturally on the Twenty-one De-

mands, from which Sino-Japanese relations did not fully recover before the

relationship radically worsened.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

838 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS

About the effort to prevent Yuan's enthronement and then to seek his ouster,

there has been an enduring interest but no comprehensive treatment, perhaps

because the movement was so diverse. The Yunnan component has received the

lion's share of attention, and legitimately so. Chinese scholarship has amended

the consignment of full credit to Ts'ai O and has brought out the importance

of pre-existing planning among junior officers in Yunnan well before Ts'ai's

arrival from Peking: Chin Ch'ung-chi, 'Yun-nan hu-kuo yun-tung ti chen-

cheng fa-tung che shih shui?' (Who was the true initiator of the Yunnan

National Protection movement?), Fu-tan

hsueh-pao,

2 (1956). Terahiro Teruo

has seconded this judgment:

Chugoku

kakumei no shiteki tenkai (The historical

unfolding of the Chinese revolution). New meanings are added to the episode

by the work of Donald S. Sutton,

Provincial

militarism and

the Chinese

Republic:

the Yunnan Army, ipof-2j, which places the affair in the context of the Yunnan

Army's evolution and its contribution to the emergence of warlordism. As

one might expect, then, if the subsequent warlord period was conceived in the

early republic, the paternity was multiple.

5. THE PEKING GOVERNMENT,

I

9 I 6-2

8

Although the primary sources are rich and the contemporary phenomena of

warlordism and intellectual revolution have received considerable attention,

the Peking government has been little studied. For an overview of the 1916-

28 period in historical context, see J. E. Sheridan, China in

disintegration:

the

republican

era. For institutional studies of the central government, see Ch'ien

Tuan-sheng,

The government

and

politics

of China, 1912-49, reprinted paperbound,

and Franklin W. Houn, Central

government

of

China,

1912-28:

an institutional

study.

More recent is Andrew J. Nathan,

Peking

politics,

1918-2y.

factionalism

and the

failure of constitutionalism.

These works rely in part on contemporary Chinese newspapers, such as the

Shun-t'ien

shih-pao

(Peking),

Shen

pao (Shanghai), and Shih pao (Shanghai), as

well as on the foreign press in China. The newspapers are available for further

research, as is an invaluable clipping service, Hatano Ken'ichi,

Gendai Shina no

kiroku (Records of contemporary China), which from 1924 to 1932 reprinted

some 400 pages per month of key articles from Chinese newspapers. For a

deeper understanding of political events, it is useful to supplement newspapers

with contemporary Chinese, Western and Japanese memoirs and observations;

for initial guidance, see George William Skinner, et al., eds.

Modern Chinese

society:

an

analytical

bibliography.

Many essential facts and verbatim documents

are also recorded in roughly contemporary Chinese works like Liu Ch'u-

hsiang,

Kuei-hai cheng-pien chi-lueh

(A brief record of the 1923 coup); Sun Yao,

Chung-hua

min-kuo

shih-liao

(Historical materials of the Chinese Republic); and

Ts'en Hsueh-lii's

nien-p'u

of Liang Shih-i.

Much more can be learned from less used types of materials. Chinese govern-

ment organs documented their work in voluminous gazettes which throw

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS 839

light on what government officials at and below the cabinet level believed in,

hoped to achieve, and did achieve. Among those surviving are

Cheng-fu kung-pao

(Government gazette), the gazettes of many of the ministries, those of the 1916-

17 House and Senate, and those of such miscellaneous organizations as the

1925 Reconstruction Conference. In addition, the government published the

quarterly

Chih-yuan

lu (Register of officials), through which researchers can

trace continuity and change in higher bureaucratic appointments.

Diplomatic archives represent another under-used source. Whether one

interprets the diplomacy of the early republic in conventional terms as a disaster

for China, or more positively as in this chapter, the story of how the Chinese

and the powers conducted themselves needs to be looked at more closely. The

only modern work on the subject is Sow-theng Leong,

Sino-Soviet diplomatic

relations,

1917-26. Leong's bibliography lists the published and archival Chinese

Foreign Ministry documents he consulted. For the Ministry's collection on

Sino-Japanese relations, see Kuo T'ing-yee, comp. and J. W. Morley, ed.

Sino-Japanese

relations, 1862-1927: a checklist of the

Chinese Foreign

Ministry Archives,

with a useful glossary of Chinese, Japanese and Korean names. American,

British and Japanese diplomatic materials, in both published and archival form,

were similarly important; for a brief description of each see Andrew J. Nathan,

Modern China, 1840-19/2: an introduction to sources and

research

aids. Diplomatic

reports are of course important for their information on internal Chinese politics.

An understanding of Peking politics requires work on related topics in

intellectual, economic and social history. So far, we know little about the

specific content of the debates over constitutional provisions that went on from

the late Ch'ing into the Nanking decade and beyond. This topic can be studied

further in government gazettes, newspapers and intellectual journals such as

Tung-fang

tsa-chih.

Meanwhile, thanks to the work of Chang P'eng-yuan (in

particular his Li-hsien p'ai yii Hsin-hai ko-ming, Liang Ch'i-ch'ao yii Ch'ing-chi ho-

ming, and Liang Ch'i-ch'ao yu min-kuo

cheng-chih)

and others like Chang Yii-fa,

we know a good deal about the basic rationale for constitutionalism and the

social and political nature of the forces promoting it.

Banking and government finance is another important topic that needs

study. Chia Shih-i's compendious Min-kuo

ts'ai-cheng

shih provides materials

whose import has yet to be fully analysed; Frank Tamagna,

Banking

and finance

in China, was an early effort that needs a successor. Numerous more or less

contemporary Japanese analyses are important for this subject. These include

Shina kin'yu jijo and Kagawa Shun'ichiro,

Senso shihon

ron; others are listed in

Skinner, Modern Chinese society; John King Fairbank et al. Japanese studies of

modern China; and Noriko Kamachi et al. Japanese studies of modern China since

19}}.

The Chinese banking magazines, Yin-hang

chou-pao

and Yin-hangyueh-k'an,

are also revealing.

To both foreign scholars and Chinese participants, factionalism is an im-

portant theme in modern Chinese history. Nathan,

Peking

politics,

provides one

analysis of what factionalism was and how it worked; slightly different in-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

840 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS

terpretations have been offered for the 1910s and 1920s by, among others, Ch'i

Hsi-sheng, Warlord

politics in China

1916-18, and Odoric Y. K. Wou, Militarism

in

modern

China: the

career

of Wu P'ei-fu, 1916-1939. See also Jerome Ch'en,

'Defining Chinese warlords and their factions'. To explain why this problem

was so severe in modern China we need more studies of biography. In addition

to Howard L. Boorman and Richard C. Howard, eds.

Biographical dictionary

of

Republican

China,

note the series of Gaimusho dictionaries under various titles.

6. THE WARLORD ERA

The sources for the study of warlordism are, like the warlord period

itself,

disordered and confusing. Most work to date has been in the form of political

biographies of individual warlords. A beginning has also been made in regional

studies. The challenge now is to find biographical materials for those who have

not yet been investigated, and local and regional historical materials for thematic

studies of the warlord era. Convenient approaches to general categories of

sources are through Stephen Fitzgerald's essay 'Sources on Kuomintang and

Republican China', in

Essays

on the sources for

Chinese

history,

edited by Donald

O. Leslie, as well as A. J. Nathan,

Modern

China,

1840-1972.

The best overall study of warlordism is Ch'i Hsi-sheng,

Warlord politics

in

China 1916-1928; Ch'i's analysis of warlord relations in balance-of-power

terms may be controversial, but he offers a great deal of well-documented

information. Lucian W. Pye,

Warlord

politics:

Conflict

and

coalition

in the

moder-

nization of

Republican

China,

delivers less than its title promises, but nonetheless

raises many useful questions. C. Martin Wilbur offers a thoughtful discussion in

'Military separatism and the process of reunification under the Nationalist

regime, 1922-1937'. James E. Sheridan devoted one chapter to a summary

description of warlordism in

China

in

disintegration:

The

republican

era in

Chinese

history.

Li Chien-nung,

Chung-kuo chin-pai-nien cheng-chih

shih (A political history of

China in the last century) is the standard survey of modern political history in

Chinese - a clear, reliable, and well-written outline of major political events.

The English translation of this work by Teng Ssu-yii and Jeremy Ingalls, The

political

history

of

China

1840-1928, is abbreviated and so does not do justice to

the original. More specifically focused on the warlords is T'ao Chii-yin,

Pei-yang

chun-fa

t'ung-chih

shih-ch'i shih-hua

(Historical tales about the period of rule by

the Peiyang warlords); not rigorously documented, but widely used. The same

author's

Tu-chun-t'uan chuan

(Chronicle of the association of warlords) on the

early warlord period has much on the intrigues preceding the 1917 restoration.

An important Japanese work is Hatano Yoshihiro,

Chiigoku kindai gumbatsu

no

kenkyu (Studies of the warlords of modern China).

There is no satisfactory military history in English for the warlord period.

Ralph L. Powell, The rise of

Chinese military

power,

189J-1912, stops when the

republic begins, and F. F. Liu, A military history of

modern

China: 1924-1949,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS 841

is largely devoted to the late republic. The basic Chinese work is still Wen Kung-

chih, Tsui-chin san-shih-nien Chung-kuo chiin-shih shih (History of Chinese military

affairs in the past thirty years), written in 1930, with a great deal of very specific

information about military organizations. Pei-fa

chan-shih

(History of the

northern expeditionary war) gives the Kuomintang view of the struggle with

the warlords.

Ko-ming wen-hsien

(Documents of the revolution) from the Kuo-

mintang Archives includes documents relating to military affairs.

Howard L. Boorman and Richard C. Howard, eds.

Biographical dictionary

of

Republican

China,

has useful details but treats only a small number of person-

ages.

It may be supplemented with the biographical sections of The China year

book,

edited by H. G. W. Woodhead, and the 1925 edition of

Who's who

in

China:

biographies of

Chinese

leaders, published by The China Weekly Review, Shanghai.

Sonoda Kazuki's biographical dictionary in Japanese has been translated into

Chinese by Huang Hui-ch'iian and Tiao Ying-hua:

Fen-sheng

hsin

Chung-kuo

jen-wu-chih

(A record of personages of new China by provinces). See also Chia

I-chiin, ed.

Chung-hua min-kuo ming-jen chuan

(Biographies of famous men of the

republic). The many small biographical dictionaries in Chinese, some devoted

to specific regions, produced in the mid republican years, must be used care-

fully; their entries are often sketchy and sometimes in error.

A substantial number of figures active in the early republic have published

their recollections. Examples are Huang Shao-hsiung (Huang Shao-hung),

Wu-shih hui-i (Recollections at fifty); Ch'in Te-ch'un, Ch'in

Te-ch'un

hui-i lu

(Recollections of Ch'in Te-ch'un); Liu Ju-ming, Liu

Ju-ming

hui-i lu (Recol-

lections of Liu Ju-ming); Liu Chih,

Wo-ti hui-i

(My recollections); Ts'ao Ju-lin,

l-sheng

chih

hui-i (A lifetime's recollections). Hsu Shu-cheng's son has published

his father's biography in Hsu Tao-lin, Hsu Shu-cheng

hsien-sheng

wen-chi nien-p'u

ho-k'an

(Selected writings and chronological biography of Mr Hsu Shu-cheng).

Shorter recollections, and other biographical and autobiographical materials

appear regularly in the periodical

Chuan-chi wen-hsueh

(Biographical literature).

Of great interest to warlord studies are the autobiographical materials in

the Chinese Oral History Project of the East Asian Institute, Columbia Univer-

sity. Te-kong Tong, ed. The

memoirs

of Li

Tsung-jen,

has been published. 'The

Reminiscences of General Chang Fa-k'uei as told to Julie Lien-ying How'

(the portions relating to the warlord period are open under certain conditions)

is a candid and fascinating account.

Among political biographies in English, Donald Gillin has written about the

'Model Governor' in Warlord: Yen

Hsi-shan

in

Shansi province

ipii-ipjp. The

'Christian General' has been studied by James E. Sheridan,

Chinese

warlord:

the

career

of

Feng

Yu-hsiang.

Odoric Wou, cited above, examines the one-time

head of the Chihli Clique, Wu P'ei-fu. Winston Hsieh discusses the intellectual

life of

a

southern militarist in 'The ideas and ideals of

a

warlord: Ch'en Chiung-

ming (1878-1933)'. Each of these men left a substantial body of writings. For

books and articles about them in Chinese and Japanese, see the bibb'ographies

of the above studies.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

842 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS

Diana Lary,

Region and

nation:

The

Kwangsi Clique

in

Chinese politics

1923-1

studies one of the main warlord groupings and offers acute insights into the

nature of regionalism and militarism in modern China. Also focused on region

rather than individuals is Robert A. Kapp,

Szechwan

and the

Chinese

Republic:

provincial militarism and

central

power,

1911-19)8. David D. Bnck,Urban

change

in

China:

politics and development

in

Tsinan,

Shantung,

1890-1949, is a study in urban

history, but throws a good deal of light on economic and social problems.

Gavan McCormack,

Chang

Tso-lin in Northeast China 1911-1928: China, Japan

and the

Manchurian

Idea, studies not only the most powerful of the northern

warlords, but also Japanese activities in Republican China.

Reports from foreign diplomats, journalists, missionaries and travellers are

extremely useful, even when coloured by the prejudices or preconceptions of

foreigners. The large British consular network in China made the Foreign

Office archives very valuable. The Foreign Office file FO 228 contains consular

correspondence from 1834 to 1930. FO 371 contains political correspondence

from 1906 to 1932. Many files in the Public Record Office in London have been

microfilmed for major research repositories such as the Center for Research

Libraries in Chicago. Slightly less full, but still very useful are the United States

State Department's 227 microfilmed rolls of correspondence relating to internal

Chinese affairs from 1910 to 1929. Japanese diplomatic archives constitute an

extraordinarily rich source that most warlord studies have utilized only slightly,

if at all. Two helpful guides are Cecil H. Uyehara, comp.

Checklist

of

archives

in the

Japanese

Ministry of foreign Affairs, Tokyo, Japan, 1868-194j, and John

Young, comp. Checklist of

microfilm reproductions

of

selected archives

of

the Japanese

Army, Navy, and

other government

agencies,

1868-1943. C. Martin Wilbur and

Julie Lien-ying How, eds.

Documents on

communism,

nationalism and Soviet advisers

in China, 1918-192/ contains documents relating to warlords, especially Feng

Yu-hsiang.

Few have attempted what might properly be called a social history of warlord-

ism. One interesting work - an attempt at 'social history through popular litera-

ture'

- is Jeffrey C. Kinkley, 'Shen Ts'ung-wen's vision of Republican China',

Harvard University Ph.D. dissertation, 1977. Materials compiled by Chang

Yu-i,

Chung-kuo chin-tai nung-yeh shih tzu-liao

(Source materials on China's modern

agricultural history) vol. 2, deal with the period from 1912 to 1927, with ex-

cerpts from books, reports, periodical articles and other sources, reflecting

social conditions of the time.

The confusion of the warlord years makes a clear and reliable chronology

essential. That of Kuo T'ing-i has been noted above. Kao Yin-tsu,

Chung-hua

min-kuo ta-shih chi

(Chronology of Republican China) is not complete but none-

theless useful.

Tung-fang tsa-chih

(Eastern miscellany) included a chronology in

each issue, much of the material from which has formed the core of a six-

volume A

chronology

of

twentieth century

China,

1904-1949, prepared by the Center

for Chinese Research Materials.

Ting Wen-chiang, Weng Wen-hao and Tseng Shih-ying, comps.

Chung-hua

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008